At the Kumbh Mela next week, millions of pilgrims will congregate at the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna rivers in Prayagraj to celebrate the spirit of an eternal, unchanging Hinduism. However, many of the practices at the Kumbh Mela are recent innovations in Hinduism, the result of colourful turbulence in North India under the Mughals and British over the last three centuries.

Situated at a gentle bend in the silty plain, where the great waterways of the Ganga and Yamuna meet, Prayagraj is a great centre of North Indian history. Century after century, rulers made it a point to advertise their power and fame there by commissioning inscriptions, read by a literate population of merchants and priests. The Mauryan emperor Ashoka erected a pillar there as early as the 3rd century BCE.

Independent archaeologist Rudra Vikrama Srivastava, who works in the region, informed me of the presence of Kushan inscriptions, dating to the early centuries CE. They were followed soon after by Samudragupta, who violently conquered the Gangetic Plains in the 4th century CE, and added a Sanskrit praise-poem to himself on Ashoka’s old pillar. While all of these tell us Prayagraj was a trading and population hub, it’s not clear when it became a holy site – and when the Kumbh Mela actually began.

It’s possible that some moves in this direction began under the Gupta Empire (4th–6th centuries CE). The Guptas pioneered a temple-focused Hinduism that encouraged the movement of pilgrims to potent sites. A Gupta feudatory made gifts to Vishnu temples in the neighbourhood, suggesting that trade and pilgrimage routes were developing in the 5th century CE.

Sometime later, the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang witnessed a great disputation of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain monks there, suggesting that other religions also made a beeline for the great trade and pilgrimage hub. And by the late 11th century, according to an inscription discovered by Srivastava, Bargar near Prayagraj was home to one of the only known temples of Ram in northern India.

But it’s only a few centuries later that we get really detailed information about pilgrimages to Prayagraj, and it comes from an unexpected source – the Mughal court.

Mughals and yogis

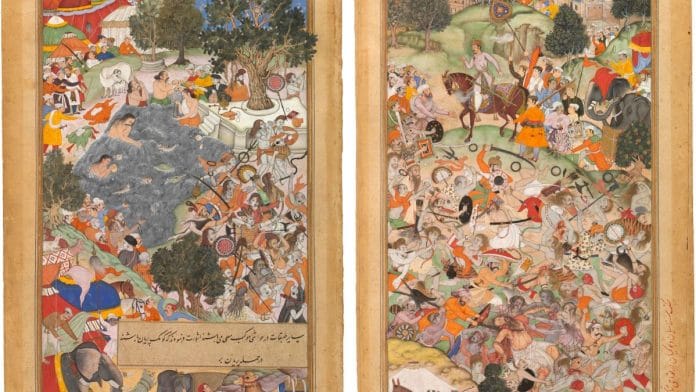

In Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires, historian William R Pinch relates an odd occurrence. In 1567, while returning from a hunting expedition, the young Mughal emperor Akbar found himself near Thanesar, where two bands of warrior ascetics were about to come to blows over camping rights. The weaker band appealed to Akbar for support, and he attempted to reason with the disputants. This failed, and the ascetics started a battle; when the weaker band were about to be overwhelmed, Akbar ordered his troops to step in and routed the stronger side.

It is still a matter of debate who these ascetics were; some say they were Hindus and Muslims; some say they were Shaivites and Vaishnavites. But the incident stayed with Akbar, who developed a fascination with yogis that was continued by his successors. Like earlier Gangetic monarchs, Akbar, too, turned Prayagraj into a centre of his authority. He expanded the city there, naming it Allahabad/Ilahabad – both “City of God” and “City of the Gods” to appeal to his diverse subjects.

He also lifted pilgrim taxes and made endowments to various Hindu holy orders, while personally visiting and consulting with yogis on occult matters. The city’s annual Magh Mela boomed as a result: there are many documented instances of this, but they are not referred to as “Kumbh” Mela.

Prayagraj’s increasingly prosperous Prayagwal/Pragwal Brahmins began to relate stories of how Akbar was in fact a Hindu ascetic in his previous birth. Generally speaking, the Mughals continued to encourage yogis, who did not fit into our modern categories of Hindu and Muslim. Even Aurangzeb – according to a letter from the 1660s, cited by Pinch – wrote respectfully to the Delhi-based yogi Anand Nath to source mercury.

This Mughal engagement with yogis had other, unexpected consequences. Benefiting from Mughal trade networks, as well as the empire’s endless demand for manpower, Shaivite yogis emerged as trader-warlords. As Mughal power declined in the late 18th century, Shaivite yogis became the arbiters of North India’s destiny, bearing Mughal-granted titles. The most remarkable of these was ‘Himmat Bahadur’ Anupgiri Gosain, who commanded an army of over 10,000 troops in the late 18th century.

Melas at pilgrimage sites offered men like Anupgiri lucrative markets and pliant devotees. This led yogi orders to compete for the right to bathe in rivers before others, displaying both their power and their holiness. More importantly, yogi orders also struggled to control mela markets – with disastrous results.

In Haridwar in 1760, according to historian James Lochtefeld in God’s Gateway: The History and Development of a Pilgrim Centre, Shaivite and Vaishnavite ascetics fought a battle that killed 18,000 people. While certainly an exaggerated number, the Vaishnavite ascetics ended up being banned from Haridwar for some time, and the Shaivite yogi orders made a killing by trading in silk, spices, and other valuable goods.

Also read: A Sanskrit Bible story was written in Ayodhya. The patron was a Lodi, the poet a Kshatriya

Brahmins and the British

As late as 1790, Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula of Awadh – a successor to Mughal authority in Prayagraj – was trying to keep pilgrim taxes low. But, as historian Kama Maclean writes in Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, all this changed with the ascent of the East India Company in the region, which was due to the assistance of the yogi–warlord Anupgiri Gosain.

Unfortunately, the British were far more paranoid about warrior ascetics than the Mughals, stripping them of their mercenary and trading functions and reducing most of them to vagrants. The Company’s paranoia also extended to various petty rulers who visited Prayagraj with armed retinues. Seeking to crack down or at least profit from pilgrimage, they raised pilgrimage taxes – to the delight of British missionary organisations.

This, however, alienated the city’s Pragwal Brahmins, who joined the mutinous Sixth Native Infantry in the 1857 uprising. The British then wreaked their ire on the Pragwals, driving many of them into penury. Pragwals and ascetics had made their livings in Prayagraj primarily from pilgrimage; clearly the British were there to stay, so something had to change. This was to effectively rebrand the city’s annual Magh Mela into a massive, twelve-yearly Kumbh Mela, organised in collaboration with the colonial state.

This involved a series of innovations. For one, as historian Manu Pillai has argued in Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu Identity, the British understood Hinduism primarily through the lens of Christian ideas – which is to say they accorded primacy to texts, not practice. If something was in a Sanskrit text, it was “real” Hinduism, otherwise it was “degenerate” and could be disposed of. So Pragwals produced Sanskrit texts such as the Kumbhaparvan, studied by scholar RB Bhattacharya in a 1977 edition of Hindutva magazine.

These texts declared that the nectar from the churning of the ocean had fallen from a pot (kumbha) at Prayagraj, leading to the eternal celebration of the Kumbh Mela. They also declared the ford to be a triveni, a confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati rivers – ubiquitous today, the terms first appeared only in 1873. The Hindi scholar Lakshmidhar Malaviya remarked drily that Prayagraj’s Prayagwal Brahmins “dug a 500-miles-long tunnel to take Saraswati to Prayag”. This coincided with an explosion in Hindi printed media, much of which was devotional. And all this reconciled the British to the idea of a large pilgrimage gathering at Prayagraj, under their control.

The British lifted the pilgrimage tax, undertaking a series of massive organisational and infrastructural works to ensure pilgrim safety. They negotiated with ascetic orders to determine their order of bathing, reducing their fearsome weapons to largely ceremonial props. Then, mobility boosted by British railways, millions of middle-class Indians, won over by print media, began to congregate at Prayagraj.

Many wrote approvingly of British efforts, and came away with a feeling of new spirituality – which directly contributed to a new Hindu identity and ripened, in time, into nationalist sentiment. Indeed, even a rationalist like Jawaharlal Nehru declared Prayagraj to be a place of timeless spirituality and had a handful of his ashes immersed there.

The point of all of this is in no way to refute tremendous power of belief that, even now, brings tens of millions to Prayagraj. Instead, I want to argue that the contours of belief – the banks that contain its torrent – are shaped by historical forces. Hinduism is often seen, due to British orientalism, as an unchanging, eternal entity. But in Hinduism’s endless capacity for innovation, to evolve alongside powerful and contradictory forces, lies its power to create such extraordinary phenomena as the Kumbh Mela, the greatest gathering on Earth.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of the Deccan’, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

There are historical records of huge gathering happening in Magh month every 5 years in Prayagraj where last Hindu/ Buddhist king Harshwardhana donated his all in 7th century….but this ignorant , communist mindset writer doesn’t know iota of that history.

This is not a research but opinion. But this guy never understands Hinduism but find faults. I have read May of his article all of them in negative tone. No genuine pride.

Print should a better person to write Indian history.