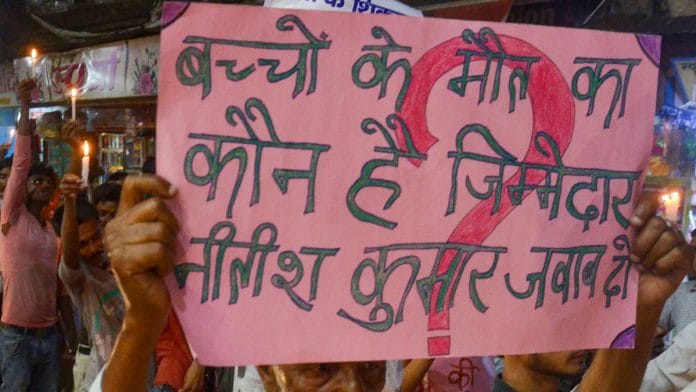

The Supreme Court Monday “came down heavily on the Centre and Bihar government” for the rising number of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome deaths in Nitish Kumar’s Bihar. It asked the governments “to file an affidavit in 10 days on adequacy of health services, nutrition and hygiene, saying these are basic rights.”

Chances are that in 10 days, we won’t remember that over 150 children had died in Muzaffarpur and few journalists will follow up on whether the governments filed the affidavit, and if so, what they had to say about the adequacy of health services in the state. Because, chances are, the news cycle would have turned three or four times by then, and we would all be outraging about some entirely different issue.

Remember my column last week? It was about violence against doctors. Do you know if all the online outrage, street protests and a national strike by doctors led to any substantial measure that would ensure doctors aren’t attacked again in India? Well, let me tell you — nothing happened. The doctors went back to work, while those of us on social media moved on to other outrages and I am sure a doctor somewhere will be attacked with the same impunity as before.

Also read: Indian TV reporters who were supporting doctors in Bengal are now harassing them in Bihar

Outrage cycles are short, acute and transient bouts of a phenomenon that sociologists call “moral panics”. Writing about moral panics in the age of hyperconnected societies a few years ago, I had contended that “it is unclear how they will affect public policy: politicians and bureaucrats can overreact to what they see as popular demand, or contrarily, tend to ignore what they see as a temporary fad among the digitally connected population.”

May be I am too pessimistic, but it appears that in India at least, outrage cycles have failed to create change. Even the #MeToo movement has run aground. You might say that it has caused greater awareness in some places and encouraged women to speak out and take action against harassment, but there has been little by way of substantial, systemic change in public policies. From political corruption to mob lynching, from train accidents to environmental crises, we lurch from one outrage to the other: deeply concerned about the issue one moment, entirely uncaring about it the next.

The reason why unprecedented media exposure and massive public attention to an issue does not lead to change — as Amartya Sen’s theory predicted — is because policy change is slow, but attention shifts fast. In fact, it shifts so fast that civil society just cannot muster up the will, resources and organisation required to sustain the demand for change. Not even for something as basic as preventing the deaths of children due to a known disease.

Also read: Encephalitis deaths: Political opportunism trumping governance in Nitish Kumar’s Bihar?

Civic activists know that it is never easy to effect change. Politicians and civil servants have existing priorities and have to contend with dozens of urgent and important matters on any given day. There is a constant and relentless battle for attention, budgets and government resources. You need to push your case through the maelstroms in the corridors of power.

As one community organiser told me, “to get things to move, you must put continuous pressure, and for that you need an organisation, and for that you need dedicated people and money.” No amount of media coverage and public attention can substitute the need for dedicated people to collect information, raise money, stand outside government offices, regularly follow up cases in court and negotiate with politicians to cross the finish line. If it is something like improving public health and ensuring that government hospitals function properly, there is no finish line. It will be a continuous exercise without an end date.

Democracy is thus a form of government where even the self-evident needs sustained advocacy. By rapidly jumping from one issue to another, outrage cycles make sustained advocacy extremely difficult. That is the challenge.

Also read: The real problem behind doctors’ strike has to be addressed, and not with a band aid

It is clear that civil society groups and policy entrepreneurs must adapt to this aspect of the information age. Conceptually there are two ways forward. One is to keep public attention focused on the issue. Biharis who want to ensure AES does not strike again must figure out ways to keep it on their government’s agenda and public discourse. Directly fighting the outrage cycle is hard, probably fruitless, but cannot be abandoned.

Another way is for activists to try and achieve a policy breakthrough before the iron has cooled down. For this to happen, civil society groups must be prepared with the tools — crowdfunding mechanisms, volunteer management systems, organisations and appropriate people. They must be ready to act as soon as the outrage cycle begins. To use the terminology that is currently in fashion: they need to conduct “surgical strikes” on the problem.

The author is the director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy. Views are personal.

How did Jacinda A in NZ do her thing so fast? Policy change is fast there and slow here in India? Isn’t that what we should learn and repeat at every instance- whether related to public safety, child rapes, doctors being beaten up. .that “will” need not be confined to Biharis or Mumbaikars or Delhiites.

Social media warriors are virtual warriors not rooted in the ground. Hence their sense of outrage is limited, or rather superficial. Real workers and transformers are usually the strong silent type that let their work do the talking.