What makes us different from the Chinese? For one, we are a criticism-surplus society.

Dissent and difference, we must remind ourselves, are foundational to democratic societies. The public culture of a robust democracy must be diverse, even contentious. India is no exception to this rule.

In fact, we Indians love to complain. We criticise everything, starting with each other and, especially, those in power — much more than is necessary, useful, or true. Criticism, for us, is a way of life. It’s how we vent our frustrations. When nothing works as it should, bitching about our lives is our safety valve. It helps us reconcile ourselves to what we cannot change.

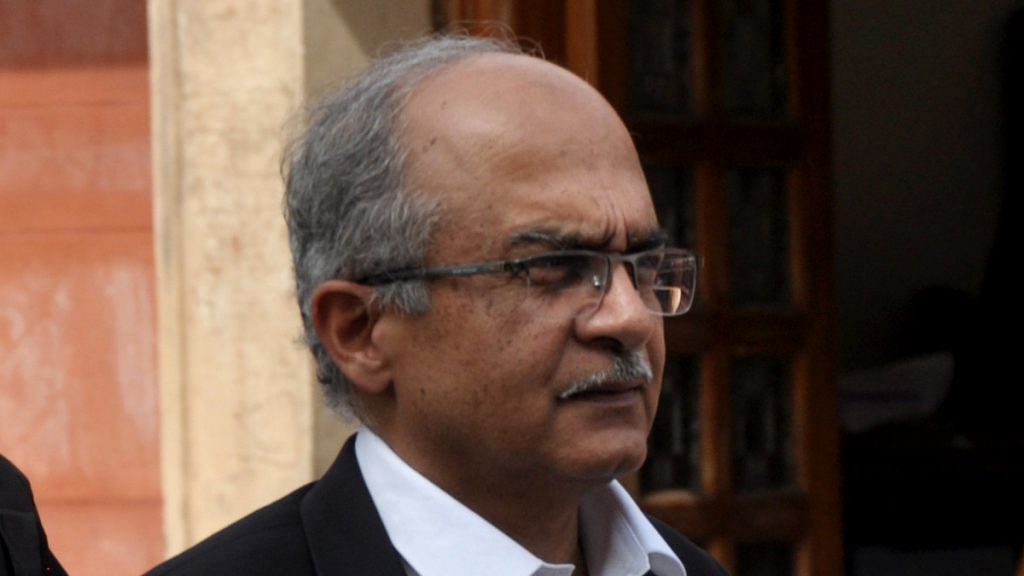

When you visit other countries, where civil liberties are not as well-entrenched or safeguarded as in India, the contrast can be striking, even breath-taking. But Prashant Bhushan’s contempt of court charges can dangerously blur that difference.

Also read: Why I look forward to Prashant Bhushan’s contempt case hearing, if it’s full and fair

Robotic China

In my eight trips to China, I was often struck by how difficult it was to get anyone’s opinion on anything, let alone on politics. Politics, as we know it, doesn’t exist in China. Anything to do with the government was, of course, off-limits except in private conversations with trusted friends or interlocutors.

In every committee, including an ordinary departmental meeting of a university, a representative of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was a mandatory presence. I asked a colleague in a leading university where I was lecturing, “Do they interfere, though?” His reply made me think. “You never know. They hardly say anything. Unless you do something that flagrantly violates the party line. But no one would dare to do that anyway. So they say nothing, know everything, and when they act, as when someone is sacked or transferred, you can’t be sure it’s because of them.” The result? One hardly speaks one’s mind.

But what about ordinary citizens, such as taxi drivers, restaurant managers, hotel staff, or, even students? It was hard to get any of them to express a view on anything other than the most mundane things. The young, I found, were vocal about products and consumer items. There they exercised choice and had opinions. But catch anyone saying that a foreign product was better than something Chinese-made and it would be couched in some sort of patriotic prattle: “Oh, we have some catching up to do there.” I was told that even about Indian films or Indian food, both of which, especially the former, have registered a rising appeal. “We need to improve the popularity of our film industry and our version of Indian food.” Just as, say, Punjabi Chinese is our favourite eat-out cuisine, the Chinese would also come up with Chinese desi, given half a chance.

When I tried to ask someone about, say, Taiwan, Honk Kong, or, worse, Tibet, I got nothing but the official line—or should I say, lie? I was repeatedly told, even by educated people, that the Chinese leadership was dedicated and excellent. They would find a solution. Intellectuals would say, “That is not my domain. Consult so-and-so who specialises in that field.” Those actually dedicated to diplomacy, policy, economics, or other government-allied fields would only offer pragmatic and useful inputs. Not speculative or innovative ideas that had little practical value. “We are trying to build a great country,” I was told, “we don’t have time or the luxury for such non-focussed or useless mental stimulation.”

Even ordinary people, whom I tried to talk to about simple things such as food, clothes, housing, or retirement plans, gave non-committal answers. Whatever you asked, the usual answer was “Oh yes, that is good”, or “Life is good”, or “Books are very good.” Not which author was better than others, or what happened to your grandparents during the Cultural Revolution, or what’s the difference between Marx and Mao.

Everything was all right and if it was not, the leaders would take care of it. Their leaders, unlike ours, were never seen, except on special, well-orchestrated ceremonial occasions. But just because they were not in your face, didn’t mean that they were not omnipresent, omnipotent, or omniscient. In the end, despite so much cultural, linguistic, geographical, and social diversity, I found much of China to be metaphysically and spiritually monotonous, even arid. The body language of a disciplined, compliant populace is robotic, in addition to being too orderly.

Also read: Prashant Bhushan’s refusal to apologise puts him in the same league as Gandhi and Mandela

Democracies need dissent

Apart from China, even ethnically Chinese-dominated free states such as Singapore tend to be highly regulated and controlled. When I first visited the island-nation, considered by some to be a contemporary version of Plato’s republic, I was told, only half-jokingly, “Even the birds must take Lee Kuan Yew’s permission before they can chirp in the morning.” Lee was Singapore’s extraordinary founding Prime Minister and ruled from 1959 to 1990 with an iron hand, more or less. Now his son, Lee Hsien Loong, is in charge, having been the Prime Minister for the last 16 years, since 2004.

In Singapore, both the free press and the right of dissent of opposition politicians and private citizens have been curbed quite effectively through legal and judicial means. In most cases, dissent has been, quite literally, driven to bankruptcy through relentless litigation under laws that are too strict to tolerate the criticism of the government or those in power beyond tepid and enforceable boundaries.

Authoritarian societies, even when well-managed, are not very attractive to live in. They do not nurture the human spirit. I know that this is not likely to ever happen in India.

But strong states, strong leaders, and strong ideologies function very differently in democracies than in dictatorships—they show magnanimity, confidence, and respect for differences of opinion. Homogeneity of opinion is soul-killing. Unity, let us remember as Prashant Bhushan faces sentencing for contempt, is not conformity.

If he goes to jail, Bhushan will be a hero, a martyr even to the cause of the right to dissent. He has already been compared to Gandhi and Mandela. But the Supreme Court may end up seeming just a little more unforgiving and less secure.

The author is a Professor and Director at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla. His Twitter handle is @makrandparanspe. Views are personal.