Bangladesh model is against subsidy driven construction of toilets, focusing instead on generating collective community demand.

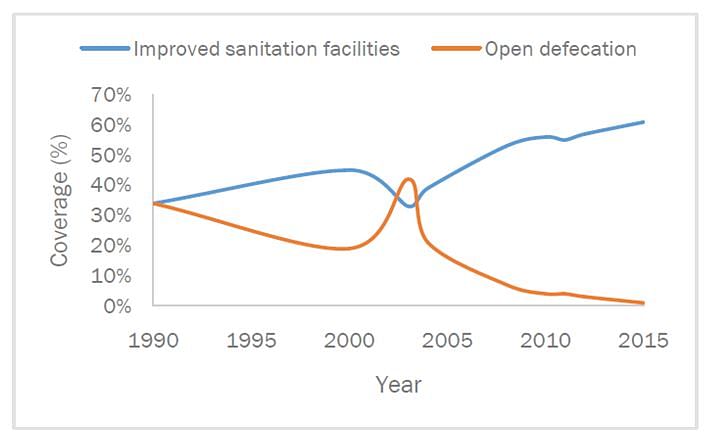

A year before Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his ambitious Swachh Bharat Mission (SBA) in India, a fascinating sanitation story was taking shape in neighbouring Bangladesh. Its open defecation-free (ODF) rates fell from 42 per cent in 2003 to 3-5 per cent between 2010 and 2015. In 2015, the WHO-UNICEF Joint Monitoring Committee (JMP) report noted the rates fell to 1 per cent. By 2017, the report noted that Bangladesh was “close to eliminating open defecation”.

Given our shared history and many similar social norms, Bangladesh’s success is an experiment India must study.

A government of Bangladesh paper from 2016, presented at the Sixth South Asian Conference for Sanitation in January 2016, noted the drop in open defecation till December 2015, and found that “improved sanitation coverage was at 61 per cent, an increase of 28 per cent since 2003”.

Also read: No, Modi’s Swachh Bharat is not like earlier sanitation measures, it’s much better

This was a remarkable turnaround for a country that, not too long ago, had characteristic plastic or leafy enclosures in open spaces outside rural homes for defecation. “Hanging latrines”, made of wood with faeces dropping into household water bodies, were also common. In the 1960s, these were forcibly removed. These scattered sanitation programmes either had problematic coercive overtones or tried the subsidy route without much success.

Birth of CLTS model

In 1999, what is now known as the Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) model took birth in Bangladesh. The CLTS model of behaviour change is followed in various countries today, including India.

The model was against subsidy driven construction of toilets, focusing instead on generating collective community demand for the most basic indoor toilets – the double-pit design. It introduced the often-quoted term, “Open Defecation Free” (ODF), stressing on the metric of toilet use. The term is, of course, now widely used in sanitation, although mostly focused on the construction of toilets. But Kamal Kar, its architect, in an interview once said that ODF status was not about “a tsunami of toiletisation”.

CLTS aggressively used shaming techniques in its communication strategy to highlight the public health ramifications of open defecation, stressing on themes like hygiene in provocative ways – like using local words for faeces repeatedly during village meetings, having community workers call village meetings in public areas that people used for defecation, thus forcing people to “smell” these surroundings, and using creative ways to explain the “dangers of eating the neighbour’s faeces”.

Facilitators asked villagers for a glass of drinking water. They then used a stick or strand of hair to touch the faeces on the ground, put it in the glass, and then offered it to people to drink. When people refused the water in disgust, officers explained this was how they consumed their neighbour’s faeces daily. Where people defecated in water, the same exercise was repeated with a bucket of water.

CLTS has been criticised for these provocative shaming campaigns. In response, CLTS advocates have cautioned facilitators to try these approaches only after building adequate rapport with the community so that the exercise is not interpreted as one that insults locals.

Also read: Amitabh Bachchan may be a great actor but even he can’t get Indians into toilets for Modi

The theory has since distinguished between “good shame” and “bad shame”, defining good shame as one where a skilled CLTS facilitator ensures “the community participates” in the process and “comes to a verdict that they are indeed eating their own shit”, with “the facilitator only taking up the cue that has already been provided by the community”.

In another interesting example of CLTS, snake bites were linked to open defecation in Nigeria, framing the use of toilets as a way to protect oneself against snake bites.

With improvement in toilet usage rates, Bangladesh deployed sanitation marketing techniques since 2009 to inspire people to build superior toilets, in campaigns such as “What colour latrines would you like”. The objective was to ensure “families have the desire and the agency to move up the sanitation ladder on their own.” International NGOs like the Dutch WASH Alliance lent support to micro-financing initiatives that helped locals set up supplies for toilet construction. Women from the community were particularly encouraged to set up shops to sell toilet hardware.

Making toilets the social norm

The 2003 National Sanitation Campaign placed the onus of achieving ODF on local government units – union parishads. Many of them experimented with different methods, like roping in local NGOs or trying other non CLTS-based interventions such as subsidies. The campaign’s great success, as has been noted by numerous international agencies, was that it could position toilets as a necessity in the community so that even the poorest were invested to use the most basic toilets. The 2015 WHO-UNICEF JMP noted that reductions in rural open defecation had “primarily been among the richest in Southern Asia, except in Bangladesh”. Thus, Bangladesh made the use of toilets the norm.

Fewer people in Bangladesh had expensive toilets, but a lot more were using at least some or the other form of toilets. Aashish Gupta and Sangita Vyas from the RICE pointed out in 2014 that the Demographic Health Survey data from India and Bangladesh presented a stark comparison. “In India, 37 per cent had a toilet that flushes to a sewer system, septic tank, or pit latrine, while 57 per cent defecated in the open. When the same survey was conducted in Bangladesh in the next year, only 12 per cent of households had a toilet that flushes, and only five per cent defecated in the open”.

Also read: In mad race for targets, Modi’s Swachh Bharat could fumble the same way UPA plans did

Follow-up studies have largely pointed to the sustenance of community driven and participative toilet use behaviours in Bangladesh. In 2009-2010, a World Bank study of 53 unions that achieved ODF between 2003 and 2005 found that 89.5 per cent of survey households “owned or shared a latrine that safely confined faeces”. As one of the researchers in this study writes, “Only 2.5 per cent households had reverted to open defecation, and 8 per cent were using latrines that did not confine faeces.”

Involvement of NGOs

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have historically helped reinvigorate not just Bangladesh’s sanitation programme, but also other public health campaigns like utilisation of ORS solutions to prevent diarrhoeal deaths.

NGO BRAC, credited with normalising ORS, was also heavily invested in the water and sanitation programme. WaterAid and several other NGOs, including World Vision, Practical Action, NGO FORUM, and Max Foundation, supported the open-defecation campaign at the grassroots in a scale that has not been seen in other countries. Experts have said this could be because NGOs have historically been involved in providing public health services, or that communities in Bangladesh trust them more than elsewhere.

Against indiscriminate subsidies

Many experts have noted that those who pay for a toilet are more inclined to use it. Giving free latrines means people always wait for subsidies. Bangladesh has invested a lot of energy to ensure that only those who really need the subsidies receive them. NGO BRAC’s Targeting Ultra-Poor (TUP) programme helped identify people who needed subsidies through community consensus. It seems the state sanitation programme in Uttar Pradesh has emulated this under the SBM, with what it terms “demand compression” of subsidies.

Also read: The ‘c’ in Swachh Bharat is caste and Modi needs to address it

The Road Ahead

Now that toilets are being used in Bangladesh, the country is facing a fresh challenge – safe disposal and management of toilet waste.

WHO-UNICEF’s JMP report cautioned that the access to “safely managed sanitation” in rural areas, which primarily captures the management of safe disposal of toilet waste, is inadequate in over 30 per cent homes. In addition, the report noted the while the country has developed infrastructure for 97 per cent access to basic water supply, only 56 per cent is safely managed.

Faecal sludge management has now emerged as a huge problem due to narrow roads and absence of sewage systems. For pit latrines, people often leave the waste buried and shift their toilets, or dump the decomposed waste.

The WHO-UNICEF JMP categorises an ‘improved latrine’ as one which confines faeces in a pit or septic tank, with or without a water-seal. The JMP excludes latrines shared by more than one household from its ‘improved’ category. But the Bangladesh government’s ‘hygienic latrine’ definition, in contrast, includes latrines used either by one or two households, of up to 10 people, with intact water-seals. In Bangladesh, in slums particularly, many households share toilets. Experts have been calling for the recognition of shared latrines.

The JMP report also outlines the challenges of inequalities in quality of toilets and waste disposal methods in rural areas. Over 40 per cent of all latrines in Bangladesh are classified as “unimproved”, and if shared latrines were included in improved latrines, this number would only come down to 25-30 per cent. In 2016, the government of Bangladesh estimated that 10 per cent people are using “unimproved” latrines, and 28 per cent are “sharing” toilets.

(This is the fourth in a four-part series on Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. Read the first, second and third part.)

Pritha Chatterjee is a journalist and a PhD student in population health sciences at Harvard University.

Feel very happy to read good stories about Bangladesh. It has proved its detractors wrong, is poised to move past us in per capita income in 2020.

“[Bangladesh] is poised to move past us in per capita income in 2020.”

This is nonsense, and very simple to detect as such :

Bangladesh per capita GNI (PPP) – 4040 us dollars (2017)

India per capita GNI (PPP) – 7060 us dollars (2017)

To catch up to India in three years,

Bangladesh’s real growth rate would have to be MORE THAN ([(7060)/4040]^.33 – 1)*100 = 20 percent per annum.

That’s not happening.