Is there a reason why the same Hindus who added “the Great” to Akbar’s name, and who have nothing against Jahangir or Shah Jahan, nurse deep hurt and resentment against Aurangzeb?

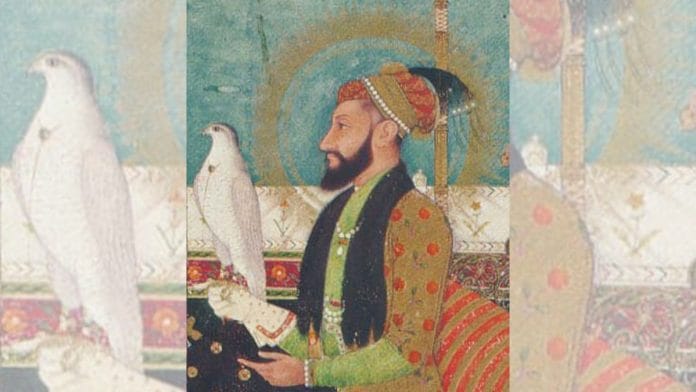

Conversely, is there a reason why the same Muslims who are critical of Akbar for his religious policy of liberality and find nothing particularly admirable in Jahangir or Shah Jahan display a profound adoration for Aurangzeb? They revere him by adding to his name the Islamic formula for invoking god’s mercy for a soul, Rahmatullah Alaihi. His regnal name, Alamgir, is a common name in the community—certainly more common than Akbar.

Muslims, whether orthodox or Left-liberal, at the slightest of criticism, jump to Aurangzeb’s defence. The orthodox glorify him outright, while the Left-liberal ones try to explain away his policy and prejudice by citing the inevitability of political dynamics as the extenuating factor.

The reason why Hindus bear a grudge against Aurangzeb is obvious. He was a narrow–minded bigot who flouted every tenet of kingship in dealing with his Hindu subjects. He persecuted them, demolished their temples, imposed Jizya, taxed their pilgrimage and festivals, imposed discriminatory taxes on their commerce, exacted back-breaking land revenue, added insult to their injury, and rubbed salt into them. This is also why Muslims adore him.

Is there a chance that Muslims revere Aurangzeb because he gave maintenance grants to some temples or because there was a relatively higher percentage of Hindus in his nobility? Perhaps because he was a pious man who met his personal expenses by sewing caps and copying the Quran? Well, for every grant he gave to a temple, Aurangzeb demolished a dozen others. Every act of his publicised piety was outstripped by his innumerable cruelties—not sparing even his own father and brothers.

So, let’s be honest and set aside such despicable chicanery of narrativist history. Muslims venerate Aurangzeb because he showed Hindus “their place”. He was the ideal Islamic ruler—by far, the most Islamic of all the Mughal and Sultanate rulers—the only one whose name is adorned with an honorific prefix and a benedictory suffix: Hazrat Aurangzeb Rahmatullah Alaihi!

Contradictory histories

Indian Hindus and Muslims have differing and, quite often, contradictory views on history. One’s victory is the other’s defeat, and one’s heroes are the other’s villains.

Islam came to India as an invading force and remained alien. Instead of striking roots in the land and mixing with the local population, it did a double whammy—alienating the converts from their country, culture, and history. Thus, two mutually antagonistic communities, perpetually in a state of war, came into being. Naturally, Indian Muslims and Hindus usually don’t have the same view on either Akbar or Aurangzeb.

Aurangzeb is not a Hindu problem. He has been dead for over 300 years. But his legacy lives on and his ghost continues to haunt us—now in the form of supremacist Islam, separatist politics, identitarianism, and victimhood narratives.

Despite such a fraught history, Hindus haven’t had a tradition of lamentation (colloquially called vidhwa vilaap or widows’ lament) and are prone to forget or move on from their worst tragedies. So much so, that they haven’t even recorded most of what happened during Muslim rule—not even the repeated destruction of the Somnath temple at the hands of rulers from Mahmud Ghaznavi to Aurangzeb. The absence of the records of lamentation led Romila Thapar to argue that this destruction was no big deal for Hindus and that they didn’t really mind it.

Many centuries of Muslim rule notwithstanding, Hindus have never vilified any Muslim ruler. Though the nature of both the Sultanate and Mughal rule was such that no matter how good a sultan was in Muslim eyes, he couldn’t be good to Hindus. In fact, going by what the 14th-century theoretician of Islamic statecraft, Ziauddin Barani, wrote in Fatawa-i-Jahandari, the more a Muslim king oppressed Hindus, the better he was regarded.

Except for some stray exceptions, which fail to redeem the Muslim period, every ruler persecuted Hindus, demolished temples, imposed Jizya, and extorted 70 to 80 per cent of their produce as taxes. Yet, there is no vilification of even Alauddin Khilji or Muhammad bin Tughlaq.

Instead, Razia is celebrated for being a woman sultan, Sher Shah for his administration, and Akbar is the Great. Even Babur, like Humayun, had been above calumny before the mosque named after him came to symbolise the wounded civilisation of India.

Why, even Mahmud Ghaznavi doesn’t incite any strong emotions in the Hindus today. The reason is that the Muslims, whether out of sincerity or prudence, have followed the line propounded by historian Mohammad Habib in his book, Sultan Mahmud of Ghaznin (1927). They have been unanimous in Ghaznavi’s denunciation as a marauder, even though he is not condemned for being what he actually was—a Ghazi inspired by the Islamic doctrine of Jihad to destroy the religion of idol worshippers. And even though the “wealth in the temples” alibi gets on one’s nerves, it has sufficed that he has been condemned for being a greedy fanatic and plunderer. The Muslims don’t identify with him—at least, not in public discourse. If they did, it would reopen Hindu wounds, and Indian Muslims would be asked to make reparations for what their spiritual ancestors did.

Also read: Chipko inspired the world. Not all its outcomes were positive

Epitome of Muslim ruler

Like other bad memories, Aurangzeb too would have been forgotten. He would have remained confined to academic history and classrooms, and not jumped into public discourse. Actually, so it had been, and there was a cross-community consensus that Aurangzeb wasn’t conducive to communal concord. However, a book, written during the time when Muslim communalism incubated at the MAO College in Aligarh and the Muslim League was founded, changed this.

Maulana Shibli Nomani, the foremost Indian historian of Islam, a protégé of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, and a professor at the MAO College, wrote Aurangzeb Alamgir Par Ek Nazar in 1909. In the book, while recognising Aurangzeb’s excesses against Hindus, he brazenly justified them as an inescapable reaction to the community’s insubordination to Muslim rule. Instead, Shibli criticised Akbar’s policy of liberality, which so emboldened the Hindus as to invite repression by Aurangzeb.

“The Islamic world hasn’t since produced a man like him [Aurangzeb],” the concluding sentence of the book reads.

The production of this kind of literature should be understood in the context of its time. It was a period when the British were midwifing the birth of Muslim communalism. A discourse around Aurangzeb had become rife in which he was not only exonerated of the charges of discrimination against Hindu subjects but very much glorified for it. Aurangzeb was canonised as the patron saint of Muslim communalism—deservingly so.

The poet Iqbal, in his Persian work, Rumuz-e-Bekhudi (1918), while criticising Akbar and Dara Shikoh for their syncretism (he called it apostasy), exalted Aurangzeb by likening him to Prophet Abraham for his passion for breaking the Hindu idols.

Those who engage in Islamic politics, regard Aurangzeb as the epitome of Muslim ruler. When Mohammad Ali Jinnah died, Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, the chief maulvi of Muslim League, paid tribute to him by calling him the greatest Muslim after Aurangzeb.

In mainstream professional historiography, however, Aurangzeb remained a bigot and a fanatic. The nationalist historiography of doyens like Ishwari Prasad, AL Srivastava, and RP Tripathi—a liberal-secular-Hindu-Muslim-unity stream—regarded him as a black sheep who couldn’t be set up as an ideal for India’s composite culture.

By the 1960s, however, the situation changed with the ascendancy of the Muslim Marxist school of history at Aligarh. By then, secular politics had helped the Muslim gentry, the Ashraaf, to overcome the demoralisation caused by their role in the Partition. Muslim League politics was revived under the banner of Muslim Majlis Mushawarat, and Aligarh Muslim University’s Minority Character became the symbol of Muslim political renewal, which fell back into its default aggressive mode.

However, in independent India, this group needed a new paradigm and a new set of jargon to rehabilitate themselves. It was provided by a Marxist tool of analysis—economic determinism. All the wrongs of the Muslim rulers were blamed on the imperatives of economy, thus absolving the religious motivation provided by Islam.

Also read: Grok is able to say things that even Kunal Kamra can’t get away with

Humanising Aurangzeb

Irfan Habib, in his book, The Agrarian System of Mughal India (1963), rightly blamed the excessive exploitation of peasantry for the downfall of the Mughal empire. But he forgot to detect the religious hatred that impelled Muslim rulers to subject peasants to such heavy exactions. [True, there were Muslim peasants, too, but they were Indian converts. In the early stages of Islamisation, they were still counted as Hindus (Hinduaan-e Kalma-go) and not regarded in the same category as the Ashraaf ruling class of foreign origin.]

The actual rehabilitation of Aurangzeb took place with M Athar Ali’s book, The Mughal Nobility Under Aurangzeb (1966), which showed that Hindus constituted 33 per cent of the nobility. This number, far higher than even Akbar’s 22 per cent, was taken as proof that Aurangzeb wasn’t the Hindu hater he is made out to be. However, this statistical secularisation of Aurangzeb didn’t take into account that it was an artificial swelling in the number of the Hindus, owing to them being co-opted through bribery during the war against the Marathas.

This new historiography normalised Aurangzeb. Now, he became a king like any other. A well-rounded man who, like others, was only a part-time bigot. He was humanised. His policy of persecution was attributed to economic necessity and political compulsion. The incriminating evidence in his own official records and primary sources were given a lie. A new historical method of “reading the mind” was instituted, where the latent intention (niyat) of the king mattered and written records didn’t. [This method came to full fruition in Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman (1985), which argues that Jinnah didn’t really want Partition.]

Historians like Sir Jadunath Sarkar, India’s greatest modern historian, who based their books on the authentic sources, were called communal. And those who theorised with arcane interpretive tools became the high priests of the secular establishment.

Also read: Going after campuses is the toolkit of Trump, Netanyahu, Modi. Columbia University is latest

Belief vs belonging

It is said that Aurangzeb was a man of his times. No, he wasn’t. In The Discovery of India (1946), Jawaharlal Nehru calls him a “throw-back” and accuses him of “putting the clock back”. He was a plain bigot and not the complex, nuanced character he is made out to be.

Such a character shouldn’t be hovering over national consciousness for as long as he has. He refuses to fade away because his legacy lives on. The Gyanvapi mosque of Varanasi and the Shahi Idgah mosque of Mathura are the least of them. He won’t recede into oblivion unless the Muslims resolve their ideological conflict between belief and belonging—between being a Muslim and an Indian.

The chapter on Aurangzeb needs a closure, but closure is the most elusive concept in Islamic history. Truth has always been subordinate to sectarian dogma and political ideology. So, even on an event like the Battle of Karbala, in which Prophet Muhammad’s own family was massacred by fellow Muslims, there hasn’t been closure. The majority of Muslims, while expressing sorrow at the tragedy, have an ideological urge to somehow justify it with roundabout reasoning. This tradition of moral ambiguity, which doesn’t allow for calling one’s own spade a spade, is not conducive to closure.

Other communities also have their share of a problematic past. The Catholics and Protestants, the Buddhists and Hindus, and the Shaivites and Vaishnavites might have done ugly things to each other, but they have moved on; those communities are no longer the same.

Muslims, however, remain caught in a time warp. If they don’t move on, they will remain the same as their ancestors—actual or ideological—forced to engage with the good as well as the bad of this legacy. Indian Muslims are not responsible for what happened during Muslim rule. But it’s for them to decide whether they want to identify with someone like Aurangzeb.

The Quran, while addressing the Jews of Medina as if they were the same Bene Israel of the Mosaic age, makes it clear that as the legatees of that tradition, they are bound by the covenant of their ancestors. They are liable to its rewards as well as punishments.

“One can also take an active part in a community’s past crimes and be held responsible for them, such that the ‘sins of the fathers’ are justly passed on to later generations. Insofar as individuals are willing to glory in a group identity and accept its accomplishments as an extension of the self, they expose themselves to the crimes associated with that group identity as well,” reads the commentary on the Ayat 84 of Surah Baqarah (2:84) in the authoritative exegesis, The Study Quran, edited by Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

A pioneering scholar from India, Maulana Amin Ahsan Islahi, while explaining the same Ayat in his commentary, Tadabbur-ul Quran, expressed a similar opinion about the liability of the lineal descendants or the ideological successors.

Aurangzeb is not yet history. He is politics. There is no need to dig up his grave, but it’s necessary to bury his ghost.

Ibn Khaldun Bharati is a student of Islam, and looks at Islamic history from an Indian perspective. He tweets @IbnKhaldunIndic. Views are personal.

Editor’s note: We know the writer well and only allow pseudonyms when we do so.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

A trenchantly argued article which brooks no sophistry. I will limit myself to saying just this: I have no words to praise this piece or its author.