On his last working day today as Chief Justice of India, DY Chandrachud, heading a seven-judge bench, delivered a 4:3 verdict in the case pertaining to the minority status of Aligarh Muslim University. The Supreme Court overruled its own 1967 judgment in the Azeez Basha Case, which said that since AMU was established by legislation, Muslims couldn’t be said to have established it, and therefore, it was not a minority institution. However, this seven-judge bench left the vexed question of the university’s minority status to be addressed by a three-judge bench in future. The court, while giving the indicia for determining the minority status of an institution, has stressed that its history should be taken into account to decide the matter.

Few institutions could be said to have made history like AMU did. Therefore, it is surprising that the institution hasn’t come face to face with its own past. This deliberate amnesia is an act of culpable concealment. AMU, or Aligarh, as it is known in the common parlance, conjured a separate nation from thin air and carved out a country by drawing a bloody line. The Two Nation theory was produced in Aligarh; Pakistan, in the words of poet Jaun Elia, has been, “Aligarh ke laundoń ki shararat (a mischief of the Aligarh urchins)”. Little wonder that in August 1947, vice-chancellor Zahid Hussain quit his post to take charge as Pakistan’s first High Commissioner to India. His predecessor, Ziauddin Ahmad, the chief whip of the Muslim League in the Central Legislative Assembly, ran the university as the fortress of that party. First post-Independence vice-chancellor Nawab Mohammad Ismail Khan’s stature in the Muslim League was second only to Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

As for Jinnah, a frequent visitor to Aligarh, AMU was the “arsenal of Muslim India” and the students its “best soldiers”. The people who have been in control of AMU since its inception, and treated it as their fief, the Ashraafs of UP, had been so neck-deep in the Pakistan movement that the next vice-chancellor (1948-56), Zakir Husain’s brother Mahmud Husain Khan, was a minister in the Pakistan government. And, on this side of the Radcliffe Line, Husain went on to become the president of India.

So, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru came to Aligarh in January 1948 to address the convocation, he spoke to the congregation as if they were Pakistani nationals. He talked in this vein notwithstanding the fact that he had come to reassure them of a secure future in the same India that they had divided but hadn’t left — for they realised that their entitlements as the former ruling class would be better served here.

Nehru reassured them that India bore no ill will toward Pakistan, and said, “I have spoken of Pakistan because that subject must be in your minds and you would like to know what our attitude towards it is.” The reality was so stark that there was no room for any pious pretence and the university community couldn’t muster the moral courage to register a righteous remonstrance at the Prime Minister’s candour. How could they, when the Pakistan Army was scouting for officers on the AMU campus, and a sizeable number of students and teachers were preparing to leave for the newly created nation?

Also read: Is asking Muslims to introspect too much? They need to resolve belief & belonging

A ‘Muslim Vatican’ from the start

AMU’s so-called minority character is essentially political and has little to do with the preservation of religion or promotion of education. AMU’s Islam is more about politics than piety. As for the fiction of the promotion of education among the minority, not more than 1 per cent of educated Muslims ever attended this institution. “What Aligarh did was to produce a class of Muslim leaders with a footing in both Western and Islamic culture, at both in British and Muslim society and endowed with a consciousness of their claims to be the aristocracy of the country as in British as in Mughal times,” writes historian Peter Hardy The Muslims of British India (1972).

The Simla Deputation of 1906, which demanded a separate electorate and was the precursor of the Muslim League, envisaged the proposed university as the Muslim Vatican: “We are convinced that our aspirations as a community and our future progress are largely dependent on the foundation of a Mohammedan University, which will be the centre of our religious and intellectual life.”

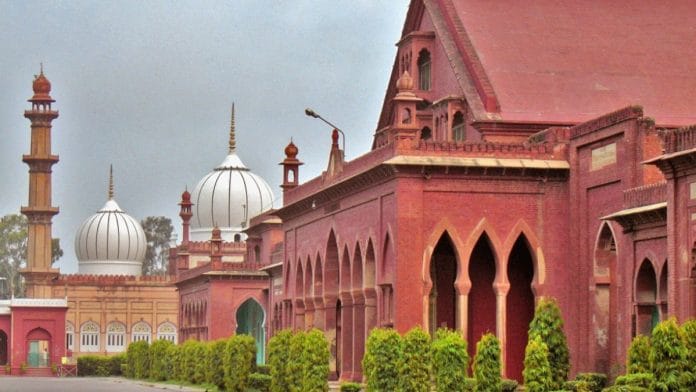

AMU, since its origin as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College College in 1877, has been a political institution. The Viceroy, Lord Lytton, had come all the way from then-capital Calcutta to lay the foundation stone. One might wonder if there was any other college, before or after, whose foundation stone was laid by the Viceroy or the Governor or even by a Collector. From 1877 to 1919, that is, till just before AMU was legislated into existence in 1920 to take the place of MAO College, all the Principals of the college had been British. They were aware that the college was the new political centre of the Muslim ruling class, which the British had conceived and midwifed as a counterpoint to the steadily growing national movement.

After 1857, the Muslim elite developed a new consensus to abjure hostility to the British and side with them to salvage whatever was left of the legacy of the Muslim rule. Now, the two would collaborate to thwart the political progress of the Hindus, who under the influence of the Bengal Renaissance and the social reform movements across India, were experiencing an awakening after centuries of slumber. The rise of the Hindus, led by their new and modern middle class, was more abhorrent to the Muslim elite than the defeat at the hands of the British. The Hindus had hitherto been their subjects. How could they tolerate their ascent to power?

The ideological ground for the collaboration between the British rulers and the ex-Muslim ruling class was prepared by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan through his novel interpretation of key Islamic concepts. In this endeavour, he was supported by the British, who, having tasted the cataclysm of 1857, were desperate to anyhow conciliate the Muslim elite. They had a dual purpose in mind — to neutralise the Wahabi fanatics, and to check the political progress of the Hindus. A strong political cadre of the Muslims, skilled in the art of new politics, was the need of the hour, and a college was needed to prepare such a cadre. But before that, a compelling narrative had to be created. Thus, the narrative of Muslim backwardness was invented on the basis of William Hunter’s book, The Indian Musalmans (1871), which was a study of Bengal. Its data about the underrepresentation of Muslims in government services were disingenuously extrapolated to the rest of India, especially the United Provinces, where Muslims were overrepresented in government services and were ahead of the Hindus in education and employment. But the false narrative suited both the British and the Muslim elite.

Any wonder why the Viceroy came to lay the foundation stone of the MAO College? The principal of the college was like the Political Agent or the British Resident on the campus. Theodore Beck (1884-99) guided Sir Syed in formulating his rabid response to the Indian National Congress, thus marking the formal beginning of the Two Nation theology. A later principal, William Archbold (1905-09), was the spirit behind the Simla Deputation, and the author of the address they presented to the Viceroy, Lord Minto.

Also read: Why do Indian Muslims lack an intellectual class? For them, it’s politics first

Nehru going easy on Aligarh

If there ever was an Aligarh Movement, it was political and not educational. One would be hard-pressed to name a few institutions established by this so-called movement. Its vehicle, the Muslim Educational Conference, was formed in opposition to the Congress and not to spread education among Muslims. Eventually, it was in the Conference’s session at Dhaka in December 1906 that the Muslim League was formed. The new party opened its headquarters at Aligarh and the rest of history is too well-known to merit a narration. Suffice it to say that Pakistan was made in Aligarh.

So, why did Nehru go to Aligarh as early as January 1948? And why was he so keen on saving AMU from a natural extinction? Two reasons could be surmised — idealism and politics. He was a high-minded idealist, and notwithstanding the pernicious role that Aligarh played with the politics of communal separatism, he was ready to give it a chance to renounce its communal ideology and join the national mainstream. He hoped that Aligarh would make a new beginning and reincarnate itself as a national institution. But that wasn’t to be. The paradoxes of Nehruvian secularism would come in the way of such a transformation. Nehru went easy on Aligarh. He didn’t call it to account for its sins. With such easy rehabilitation, there was no need for it to take stock of its past, recognise its institutional guilt, and make a clean break with its contentious legacy.

After Independence

In independent India, AMU needed a rebirth, which would not be possible without burying its old self. It was all the more crucial for the Muslim community whose ideological identity and political personality had largely been shaped by the discourse that this university generated. There’s no gainsaying that without Aligarh, Indian Muslims wouldn’t become a (political) community separate from the Hindus. Therefore, it was imperative that the Muslim community reinvented itself not as a separate but as an inseparable part of the Indian personality. But Aligarh failed in the task of the ideological reformulation necessary for the reconstitution of the Muslims into a community that recognised its Indian destiny. It was both an intellectual and a moral failure. Aligarh’s intellectual aridity is well known, but its moral bankruptcy is less recognised.

There was, however, an inevitability about this failure. An institution that was founded with the express aim of preparing a political cadre, skilled in the craft of modern politics, which could win back some of the lost privileges of the old ruling class, didn’t have the moral competence to think beyond itself. Their class interests masqueraded as minority rights, and the ordinary Muslims had to face the brunt of resentment against the appeasement politics.

Now, coming to the substantive political reason for Nehru’s eagerness to save AMU from either dissolution or hijrat (religious migration) to Pakistan, or becoming an ordinary university under the state government, let’s remember that howsoever poetic, philosophical, and idealistic Nehru might have been, he, first and foremost, was a politician. The pursuit of power was in his instinct, and he wasn’t averse to making ideological adjustments to further this end. Before Independence, he fought Muslim communalism tooth and nail, but, eventually, he conceded defeat, and India was partitioned. The country was seething with rage against the forces that led to its dismemberment. The Hindu nationalist forces — a substantial number of them in the Congress itself — were pressing for a political culture that wasn’t apologetic about India’s quintessential Hinduness. Nehru saw in them the greatest danger to his power. Though he and the country had just lost to Muslim communalism, rather bizarrely, he identified Hindu communalism as the greatest danger to the country. This valorisation set the template for the liberal-secular polity of India.

To keep the Hindu Right wing at bay, Nehru saw a natural ally in the very people who had voted for Pakistan with their feet. They were the ex-ruling class, the descendants of Muslim conquerors, and the self-styled Ashraaf. Instead of facilitating their hijrat to their Holy Land (that’s what Pakistan means), Nehru pleaded with them to stay put. AMU was the political pivot and ideological pulpit of this class. It was their Rome, with a Vatican within. The new rulers of India would make a good provision for them to live in leisurely dissipation in this quaint principality, much like how a pensioned-off nobility lives off their sinecure, seeking satisfaction for their instinct for power by in-house politicking. And so, Nehru adopted AMU. He created the concept of Central University to fund it by the central government. Banaras Hindu University (BHU) was included in the list for the sake of communal parity, and Delhi University (DU) because it was in Delhi.

In return, the Aligarh Oligarchy had to peddle the narrative that would get the Congress the Muslim vote. Even after Partition, Muslims remained wedded to the League’s, that is, the Aligarh Movement’s, ideology. They would vote only for those candidates who were supported by the (ex) Leaguers. And, the Leaguers would ask them to vote for the Congress in the name of Islam.

Donning the garb of identity politics

If there was no attempt to secularise the public discourse of Muslims, it was because Islamic politics equally suited the Muslim elite and the Secular Sarkar. Much like how Aligarh had earlier collaborated with the British against the National Movement, the New Aligarh would partner with the Secular Sarkar against the cultural nationalists. From this expediency of Nehruvian secularism, the Muslim vote bank was born, and the Two Nation Theology came out of hibernation, this time donning the garb of identity politics. By the 1960s, this politics crystallised around the issue of the minority character of AMU. Earlier, Aligarh was the centre of Muslim politics, now it became Muslim Politics itself. In due course, other issues like the Muslim Personal Law and Babri Masjid would gain traction from the politics of assertion that had begun with agitation for AMU’s minority character — a euphemism for its Muslim-political character.

Let there be no confusion that the legal wrangle over the minority status is for 50 per cent reservation for Muslims in admissions. In reality, it’s for the formal recognition of AMU as the ideological centre of Muslim politics. If it is conceded, the history that already ended in tragedy will repeat itself as farce.

Ibn Khaldun Bharati is a student of Islam, and looks at Islamic history from an Indian perspective. He tweets @IbnKhaldunIndic. Views are personal.

Editor’s note: We know the writer well and only allow pseudonyms when we do so.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

I somewhat prided myself, I must confess, on knowing whatever was worth knowing about AMU, its past, the way it came into being, the idea behind it and so forth. But that was before reading this article by this intrepid and towering intellectual, Ibn Khaldun Bharati. He is in a class of his own… This piece presents such a coherent account of the formation and the legacy of one of the most talked-about and argued-about institutions in the sub-continent that I cannot but be awestruck.

I Shariq Adeeb Ansari as a National Working President of All India Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz I wholeheartedly respect the Supreme Court’s judgment on the status of AMU’s minority character.

However, as an individual citizen, I feel a sense of sorrow, as this decision does not seem to serve the best interests of the community or the nation. It is high time that Aligs move away from a camp mentality, and the broader Muslim community steps out of the persecution complex. Instead, we must focus on aligning ourselves with the national mainstream, contributing to both our community and the nation’s progress.

The failure to do so over the years has unfortunately reduced our alma mater to a localized, self-serving institution—one that lacks the vision and strategy needed to address the challenges of the 21st century.

AMU is the reason why India was divided into India and Pakistan. It is solely responsible for the Partition.

As such, the best course of action will be to shut down the university. Continuation of the university risks further fragmentation of India. Over the last seven decades it has become amply clear that AMU does not identify itself with the Indian nation.