Agriculture, the largest private sector in the country, is today the most regulated sector of the economy. From ownership and use of land, to access to inputs, access to markets to sell the outputs, and the prices at which the produce can be sold, access to new technologies, are all directly or indirectly governed by a maze of laws. The economic liberalisation initiated since 1991, has simply bypassed Indian agriculture. Yet, hardly anyone denies that it desperately needs reforms.

The Narendra Modi-led government has claimed that the three new laws are re-creating the 1991 moment for agriculture. However, in 1991 the reforms were premised on decentralisation and deregulation. The new agriculture laws are centralising control over agriculture.

By its novel reinterpretation of the constitutional provisions, the Modi government has invoked provisions in the concurrent list to claim powers over the states with regard to agriculture trade and markets. On the face of it, it does curb the constitutionally mandated role of the states with regards to agriculture. The courts may eventually pronounce on the legality of this novel approach, but this is clearly a blow to the spirit of federalism.

Also read: Modi govt must sweat in Parliament to avoid bleeding on street. Farmers’ protest shows why

Undermining federalism

Agriculture, along with mining, is the only sector that is completely local, as it is tied to the geo-climatic conditions of the area. Decentralisation is a necessity in agriculture. Yet, in the name of reforms, the new market access [Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020] (FPTC Act) and contract farming [Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020] (FAPAFS Act) laws are an assault on decentralised governance.

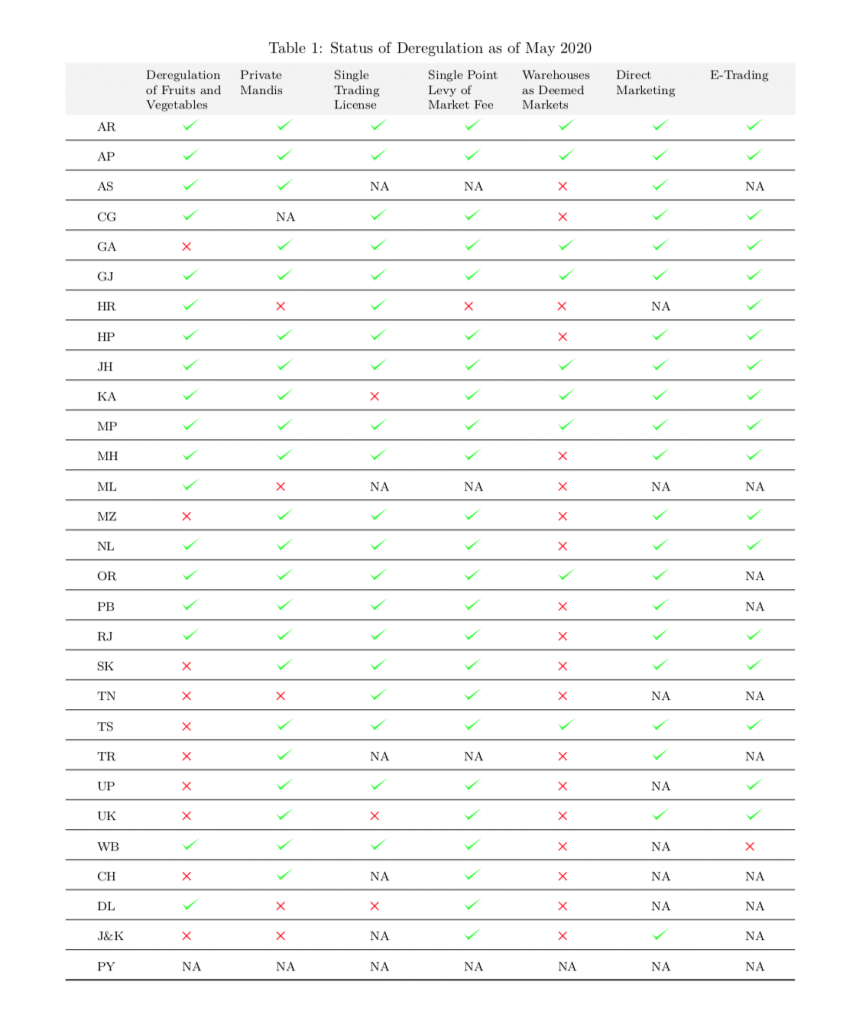

Agriculture markets are governed by Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) laws enacted by the state governments. These markets are either monopolies or monopsonies in designated areas, often entrusted to raise revenue to provide for local infrastructure, including roads etc, to serve the farmers in the area. There is inefficiency, corruption, and inevitable politicisation. For over two decades, there have been periodic efforts to reform the APMCs. Due to the federal structure, one can see a diverse range of responses at the state level.

At one end, there is Punjab and Haryana, where APMCs are most developed, and contribute a large share of food grains procured for the central pool. At another end is Bihar, which in 2006, abolished the APMC act, but where the alternative markets have not developed. Every year, there are news reports of farmers from Bihar and other northern states trying to sell their rice in the mandis of Punjab and Haryana. In Maharashtra, farmer producer organisations (FPOs) have emerged as alternative markets catering to the needs of procurement agencies, as an alternative to the APMCs.

Over the years, around 18 states have allowed private markets, 19 states have allowed direct purchase from farmers, and another dozen states have allowed farmers’ markets outside of APMC. There are less than 7,000 mandis in the country today, while various official estimates have put the required number between 10,000 and 40,000.

In any case, less than half of the agricultural produce is sold at the APMC mandis. Majority of farmers are too small to generate adequate marketable surplus, don’t take the trouble of going to the mandis. Much of it is sold locally to local traders. Recognising these local haats and markets, enabling them to develop their infrastructure, integrating them with the formal markets might be a much more economically and socially viable way to build a network of markets enhancing competition and increasing the options for the farmers. Appreciating the localised nature of the problem holds the key to understanding why alternative market mechanisms, by FPOs or private corporates, have not been able to expand beyond a few niches.

Rather than building on this rich and diverse experience, the new market access law seeks a one-size-fits-all approach. Since the central law can’t really alter the APMCs under the state laws, the new FPTC Act seeks to create a parallel marketplace and legally insulates the new markets from the purview of state APMC laws, including the state taxes and cess on such private markets. Not surprisingly, this is seen as an attempt to sidestep the APMCs, and by extension undermine the procurement process, while curbing the state’s power to regulate and tax a part of the agriculture trade.

Also read: Kisan march pictures may not show you women farmers, but don’t forget to count their protest

The role of APMCs

There is an urgent need to discuss whether APMCs should be responsible for raising revenue for local infrastructure development. At one level, this is seen as devolution of governance, but at another level, it also leads to politicisation of market institutions, and opens up the prospect for corruption.

A much better approach would be for states to encourage and enable alternative market platforms to emerge by levelling the playing field, so that the existing APMCs and the new entrants in the market space can compete on an equal footing. For instance, the states could enable the APMCs bodies to convert into a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO), or even a private company, and then compete with other players in the market on an equal footing for the custom of the farmers. Instead, the new market access law is seeking to stifle the existing APMCs, without any regard to the local contexts, while privileging the potential newcomers. Throwing the baby with the bathwater.

The ultimate irony was that the very moment these bills were being enacted in Parliament, the government issued an order to ban all export of onions with immediate effect on 14 September. Such ad hoc decisions on onions, which are almost an annual feature , bely the promise of free trade and undermine the prospect of a contract.

Likewise, with the Essential Commodities Act, a central law protected under the Ninth Schedule, and whose roots can be traced to wartime shortages in the 1940s. However, Indian farmers have transformed Indian agriculture despite the regulatory stranglehold. The new amendment removes some of the specific commodities from the purview of the Act, but adds clauses that negate the very purpose of the amendment. The new law says, in case of a price increase of 100 per cent in case of perishable items, and 50 per cent in case of food grains, the ECA can be invoked.

Today, the country is not suffering from scarcity, but the farmers are bearing the burden of abundance. They have no assurance for trade nationally or globally, and they are not free to access the latest technology to improve their productivity. The new laws hardly testify to the sincerity of the government’s intention to free the farmers.

by Bhuvana Anand, Ritika Shah and Sudhanshu Neema

Published by the Centre for Civil Society, New Delhi, August 2020

Also read: The method in the madness of ‘jhatka’ policymaking

What next

Agriculture is currently under the spotlight, and here are three possible steps that might help find a constructive way forward.

- The Modi government should suspend the new market access law bypassing the existing APMCs. Instead, state governments need to undertake reforms to liberalise the agriculture market and trade. Competition among states may throw up the most effective models for the agriculture market, reflecting the local agriculture situation and the political economy of that state. The Centre should just ensure that interstate movement of produce is neither blocked nor restricted.

- The contract farming law should be made a model law, with the state free to adopt or modify it as suitable to meet local conditions. Nearly 25-50 per cent of agriculture is conducted under some kind of contracts, largely informal. There won’t be any need to engage in informal contracts, if the formal institutions are able to earn the confidence of the farmers.

- The Modi government should abolish, or completely remove, agriculture from the purview of the Essential Commodities Act. In order to meet the requirement of food security, as well as disruptions caused by natural calamities, the central or state governments can always purchase the necessary commodities from the market for the benefit of those in desperate need.

The amazing success of two major Indian crops in the international market over the past 10-15 years should provide a glimpse of the possibilities. India today is the leading exporter of rice and cotton, producing far beyond the domestic need, and opening the possibilities beyond the current debate over APMC and MSP.

The author is an independent commentator and a long time proponent of market reforms, with a particular interest in agriculture policies. Views are personal.

You made your comment just by seeing one side of the coin. Agriculture falls in in both centre and state subject. Centre gives msp on the procurement of crops because states don’t have enough funds for that. Around 40% of punjab farmers sell their crops directly to the traders. In fact 80-85% percent of india farmers don’t sell in mandis. So how do mandis violate article 301. In fact after the law a monopoly of corporates is certain on the agriculture sector. Farmers will only benefit from the corporates till mandis are not destroyed. As I said 80% of India farmers sell to traders and only 6% of India farmers get msp, you can imagine the gap. Corporates will give high prices to farmers for only a few years eventually shutting down the mandis. Most of the marginal farmers can’t even sell their products from one to another district and the government is making dreams of inter state marketing. I am agreeing with you on bihar’s situations. In my analysis I find that this act will only improve the situation of marginal and small farmers when corporates show their mercy. Most of the farmers are illiterate so how can you imagine that they will understand all the terms and conditions. This act makes farmers’ side weaker. I agree that this acts have a lots of pros but we shouldn’t ignore the tons of cons.

I think the politics should be separated from yhe policy. It is also a question of using MSP to incentivise agriculture reforms in the context of high malnutrition and poor calorie intake vis a vis our over- flowing grain stocks!

The protein intake and calorific food value gap between India and China has been increasing since past 20 years.

India is a vegetarian country. Its annual per capita vegetable consumption is 81 kg and China’s is 320 kg.

Both Rice and flood irrigated wheat, lead to carbohydrate intensive diets. Besides, these are high on water consumption, which is provided through subsidised electricity from our taxes.

Farmers prefer cultivatation of rice and wheat grain because of its storage resilience, transportation and ease of cultivation, as opposed to protein or vitamin intensive vegetable horticulture (which has perishablity) or oil seds and pulses which the country has to import agaisnt FE.

The Agri-reforms and MSP should incentivise cultivation of crops that the consumer needs for his family’s good health.

Both farmers and the Government have to take a broader and objective view of the purpose of the MSP.

The genuine misgivings of the farmers should be looked into and the laws modified wherever required. APMCs may be outmoded but an alternate system should be allowed and it may take time to consolidate and give a better deal to farmers. Instead of wholesale ‘reforms” incremental changes will be better and will not invite violent protests.

The author wants the government of India to use the pretext of Federalism and pass on the problems to the states instead of taking any leadership. This kind of mindset has been the bane of India.

Discussions and consultations with farmers were essential before enacting the Agri reform bills. Now the government is on a sticky wicket. The method which presumes that only one person knows what is good for the country has caused all the harm. Demonetization was also imposed in the same manner. The obstinacy can cost dearly in the long run. Government should show flexibility and roll back some of the features of the legislation in order to settle for a compromise solution.

The author wants us to believe that State governments who did nothing for farmers in the last 70 years, will do it now ?

Maybe the laws have some good points but agriculture is largely a State subject. So the Centre should readily offer to accept any State law that rescinds the Central laws. Let there be a competition between BJP and other States and lets observe over 3-5 years where farmers are benefited. That way the outsized egos of our PM and State CMs can be satisfied and a genuine competition among States can commence.

Funny how everyone suddenly remembers agriculture is a state subject. If it is so, why should the centre pay MSP. Might as decentralise that. While agree with the author’s final suggestion of doing away with ECA, the author has mistaken that the 3 laws are going to introduce homogeneity. They don’t. They have basically opened up the space for competition. The way the economic agents want to compete (FPO, cooperative, LLP, food processing, storage, finally marginal farmer) is upto them. The govt didn’t force the economic agents to structure themselves in a certain way.

The centre is well within its right to make these laws. Entry 33 of concurrent list. Might i also.point out how APMCs are unconstitutional because they violate art 301 . Funny how the author talks about exports but seems to not realise thag APMCs have broken the markets within India itself. Export tho door ki baat hain.

The bihar example. Are you all dumb? Just because bihar didn’t see infra development or entry of private players doesn’t negate the need for these reforms. Bihar isn’t even an IT power which is essentially backed by 1991 reforms. So what, we undo those too because bihar didn’t see the fruits of those results? Investment in any sector is a function of so many factors. Primarily being it should not be illegal. Which is what these laws try to do. This needs to be followed by skill training in new agri techs, ensuring contracts, rule of law, infra development etc.

Author should revisit his views.