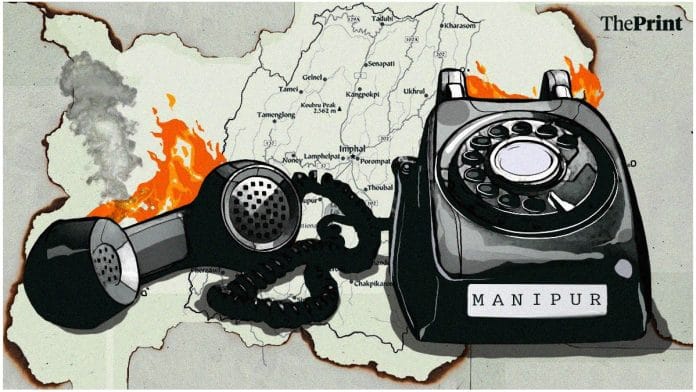

If you want to check out India’s biggest immediate security threat, internal or external, please do not look for it on most of our TV news channels. You might then be deluded into believing it’s the violence in the West Bengal panchayat elections. Look further east, find Manipur on the map. If you think it matters for you, as a patriotic Indian.

The state is caught in an anarchy not seen in any part of India for decades. Even to one inured to watching civil unrest, insurgency and terrorism for the better part of four decades, like this writer, the picture in Manipur is unprecedented.

It was one thing when these challenges came in the 50s (Nagaland), 60s (Mizoram) or even the early 80s (Punjab and Assam). But in 2023, with the kind of power the BJP has at the Centre and in the state, and with the communication, logistics, military and paramilitary forces available now?

The past is no guide to the present, especially when it comes to asserting the power of the state. So basic was the communication in the northeast even in the early 80s — when three active insurgencies still raged (Naga, Mizo, Manipuri) and Assam was in chaos — that as a reporter I had to file at least two stories from a Morse machine from the telegraph office in Mokokchung in Nagaland. Weak or nearly absent lines of communication then made the job of governance in an insurgency-hit region that much tougher, and the job of a reporter nearly impossible. Such excuses don’t exist now.

Also Read: Manipur saw ‘free’ India’s 1st flag hoisted. Now it’s BJP’s biggest internal security challenge

First, let’s see how different Manipur is from the crises of the past, the differences that make its challenge unique, sui generis.

One community has targeted the other often enough in the northeast and elsewhere in the past. In Assam, the Bengali speakers, and then more specifically the Muslim Bengali speakers, were targeted, often violently. But the state acted promptly, took tough action and restored its own authority quickly. Everybody knew who the attacker was and who the victim was. And the state rose to the victim’s defence, even if not always fully effectively.

In Tripura, we saw the smaller tribal minority (less than 25 per cent of the population) carry out targeted killings of the Bengali majority. The first and most infamous of these was the Mandai massacre near Agartala on 8 June, 1980 that left between 400 and 600 innocent villagers dead. That was put down fast, too.

And finally, we swing west to check out Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab. In the first, the Centre and the state both lost control of the situation for several months in 1990 when V.P. Singh was prime minister. Yet, the state was always fighting back. It was not seen to be in the barracks as is the case in Manipur. It sent a tough governor in Jagmohan. Police armouries were not being looted of thousands of weapons without any resistance. In Manipur, the looters are so brazen they leave behind their Aadhaar cards so that in case there is an inquiry, the cops on duty can ‘help’.

Within the northeast, probably the most dire threat came within weeks of Indira Gandhi taking over as prime minister. She was then widely seen as a not particularly powerful one. India had seen the death of two successive prime ministers in harness (Nehru and Shastri) within about 19 months. There was an environment of shakiness and insecurity.

The Mizo rebels declared “sovereign Mizoram” in what was still a mere district (Lushai Hills) of Assam, and were on the verge of overrunning the deputy commissioner’s office and the local Assam Rifles battalion headquarters. Indira Gandhi responded by unleashing the Indian Air Force on bombing and strafing missions. That act is still considered controversial and high-handed. But it also put down the rebellion long enough for the first columns of Army troops (from 5 Para) to fight their way in from the plains, nearly 200 km away.

Which brings us to Punjab in the early 80s. And the reason we left it as the last among this list of examples is because it may hold the key to what may be a way ahead. The first rash of terror killings rose in the Bhindranwale years of 1981-83. The Congress party had returned to power at the Centre and the state. Darbara Singh was its chief minister.

As the killings of Hindus, a prominent newspaper owner-editor (Lala Jagat Narain, Punjab Kesari), and a police DIG (A.S. Atwal) shook the nation, what did Mrs Gandhi do? She sacked her own party’s government and chief minister using Article 356 and imposed President’s Rule. It did not end the challenge in Punjab. But it demonstrated a willingness to acknowledge the threat and governance failure for what it was.

If the answer to every new crisis, misstep or setback is that it’s happened before, especially under the rule of the Congress, it is also useful to look back for precedents. It was no weak government in New Delhi that invoked Article 356 of the Constitution to dismiss its own full majority government in a relatively large state just 220 km from Delhi.

It was Indira Gandhi at the peak of her post-Emergency power, with a majority larger than the BJP’s today.

Also Read: A broken Manipur is out of sight, out of mind. Here’s why we can’t be so callous & arrogant

We can understand why this government may be hesitant to take a leaf out of Mrs Gandhi’s book. But, any which way you look at the situation honestly, you’d know that the state government at this point is central to the problem, not its solution.

It is trusted by neither side, its top functionaries are in hiding, and its most important responsibility — maintenance of law and order — is being performed by ‘advisers’ and officers sent in from outside. Further, its very continuation is a provocation to both sides. Kukis see it as partisan with a majoritarian agenda. The Meiteis see it as incapable of even protecting them, despite having won such massive electoral support from them.

There are several features, however, that make this ongoing Manipur disaster unprecedented. We list just three:

*We’ve had countless examples of one community targeting the other on the basis of religion, ethnicity or language. We’ve also seen two communities fighting pitched battles. This is the first time in our history that we have two communities fighting in large numbers with automatic weapons, including long-range sniper rifles that most of our uniformed forces would envy. This is a textbook civil war.

**It is the first time that while anarchy has raged for six weeks, the government has failed to come up with a decisive political response. Sending more forces that this terrain can keep consuming, sending negotiators and setting up a peace committee nobody accepts are band-aids. The wound is too big for them to contain.

***There have been umpteen cases of the exodus of one victim community. The Kashmiri Pandits, for example. In Manipur, both warring communities are fleeing. Basically, anybody who can leave Manipur is leaving. This is new.

The Centre is both empowered and charged with responsibility under Article 355 of the Constitution to protect every state from external and internal threats. If a state government fails despite all the help the Centre extends, it must go. There is no shame in it. Remember, Indira Gandhi did it.

It won’t mend this broken state instantly. That will be a long haul. But it will be a beginning, and seen as such by both sides. It will also address the only sentiment both sides share equally: that our Manipur is burning, but nobody’s bothered.