This week’s National Interest is about two things I am least qualified to write about: cinema and the insurgency in Kashmir. Cinema, because I have zero knowledge in an area in which India has the second largest number of experts after cricket. Kashmir insurgency, because by the time it peaked, I had become too old, senior and regrettably, but inevitably, too editorial to go out and report. If I am nevertheless persuaded now to wade into the storm over Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider, it is as much a tribute to the mainstreaming of mature political cinema in India as to the growing maturity of our people.

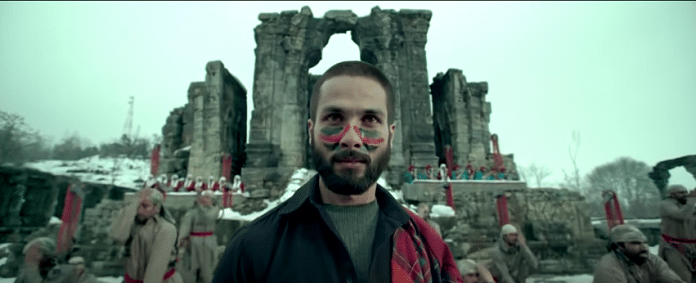

A robust campaign has been running in the social media to boycott Haider as it has been condemned as all kinds of awful things – anti-India, anti-Army, anti-Hindu and, even more specifically, anti-Lord Shiva (a key dancing sequence has been shot amid the ruins of the old Martand Temple). Yet, Haider has done quite well, so many people have paid to watch it, defying the boycott calls. It tells you how we are growing up as a society even in these times of illiberal hyper-nationalism and are now more willing to look within and at least acknowledge that there might be another side to a partisan story, however deep a shade of grey it may be. I say this also because just a year ago, another significant political film, Madras Cafe, had commercial and critical success. That, even more than Haider, scripted a story of the Indian Army and intelligence’s failures in Sri Lanka. Sure, there were protests in Tamil Nadu, but it did better than any other political film in that genre, without either Haqeeqat-ising or Border-ising it.

The last two references are to two of the most successful “war” movies in our history. I pick these two also because one was the story of a debacle (1962, Ladakh) and the other of a victory (1971, Longewala). Both had more crucial elements in common. Heroism of the Indian soldier, perfidy, even incompetence, of the adversary and, for the record, a dash of the Deol hyper. Chetan Anand had Dharmendra dying fighting at Rezang La to the heart-wrenching notes of Kaifi Azmi’s “kar chale hum fida jan-o-tan saathiyo…”, J.P. Dutta’s Border, 30 years later, featured Sunny Deol as the victorious Sikh Major who could bust a Patton with bare hands.

Haqeeqat, though bold for its times, gave the Army its best defence possible, and cemented the belief that the timidity of Indian leaders and the betrayal of the Chinese were responsible for the defeat, and not our generals. That mythology has survived three generations and is the reason why no government wants to declassify the Henderson Brooks-Bhagat report. Dutta’s sillier Border, on the other hand, launched an entirely new fiction, of India’s total military superiority over Pakistan, dovetailed nicely into the Pokharan-II and Kargil fervour which followed, and unleashed a genre of so-called war movies that had either Deol or some pretender similarly pulverising the silly Pakistanis. Until even Indian audiences got tired, and every single post-Kargil film bombed. Partly also because people had already seen that “movie” on news TV, with real soldiers.

Vishal has broken new ground in that Haider is probably the first time mainstream cinema has locked horns creatively with internal conflict, and that too something as polarising as Kashmir. From what I can recollect, the only other attempt in this area was Atma Ram’s 1972 Yeh Gulistan Hamara, starring Dev Anand and Sharmila Tagore and set amid the Naga insurgency. The film was as idiotic as your usual Sunny Deol hyper, and cinema halls got vandalised in Calcutta for running it because it demonised the Chinese! Three decades have passed since Operation Bluestar and the death of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, and two since the death and burial of the Khalistan insurgency, but Bollywood has pretended it never happened. Except Gulzar’s brave Maachis – even though, having covered that story in detail, I have differences with it, and he lets me argue with him. So are many entitled to disagree with Haider and its treatment of Kashmir. But a ban or boycott, no.

It takes a special Indian filmmaker to explore Kashmir as if the “other” side also had a story. It is, similarly, a compliment to the Indian censors, the Army and, most of all, paying public that Haider has been released in this form, torture chambers and all, and is a commercial success, defying hashtag McCarthyism.

Commercial films carry risk to investments, reputations and physical safety, particularly at a time when blind nationalism has overwhelmed rational, self-questioning patriotism. You have to be a brave and particularly patriotic Indian to explore if the other side, in this case the indigenous Kashmiri, also has a storyline, a point of view or, to flog that much misused word these days, narrative. Watch also how shamelessly cautious even I, with my skin thickened after nearly four decades in journalism, prefer “indigenous” for our Kashmiris rather than Indian. No, I do not mean they are not Indian. But if I called Haider, his father and mother and uncle and girlfriend “Indian” Kashmiris, what would you like me to call their cousins on the other side of the LoC? Pakistani Kashmiris? It is just a small illustration of how complex and sensitive this issue is.

Also read: Azaadi to autonomy

The film has its flourishes. As you would expect from a talent powerhouse that includes, besides Vishal, Gulzar, Tabu, Irrfan Khan, Kulbhushan Kharbanda and, not to forget, Basharat Peer, who is one of our most talented Kashmiri writers (besides writing the script with Vishal, he also features briefly as the silent Kashmiri, scared to enter even his own home without somebody first checking his antecedents). But the most important one is how each side sees the issue, the Army Major who says he knows that Islamabad is also a name for Anantnag but adds, looking over the horizon, “for us, it means only one thing, Pakistan”. Militants, who fight for Pakistan, never mind how many Kashmiri lives are lost. And Kashmiris themselves, crushed “like the grass when two elephants fight”. They are a test case for two viciously contradictory national ideologies, India’s secularism versus Pakistan’s two-nation theory. See also how differently even the state agencies view a militant, from the Army Major ordering the blowing up of the Kashmiri doctor’s house rather than storming it because “no militant, dead or alive, is worth more than my soldier’s life” to the cynical cop who shoots three captured suspects, because “even a dead militant is worth a lakh of rupees”.

Rather than malign the Army, Haider shows it in very fair light. No army likes to fight its own people, and that too for decades. There is no military victory in such a war. The dilemma, on this impossible military, ethical and psychological challenge, is portrayed brilliantly. Interrogation chambers, torture, disappearances, marauding killer militias raised by the intelligence agencies (remember the infamous Kuka Parray, Ikhwan chieftain?) are well documented. Talking about them now is cathartic for both sides, armed forces and Kashmiris. In a mature and confident democracy, you expect popular culture to create the space for truth-telling and reconciliation. That’s the role Hollywood has played in America, portraying, for example, the pain and dilemma of the American soldier in Vietnam and recently Clint Eastwood’s examination of Iwo Jima from both sides, American and Japanese (Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima). These haven’t weakened America, or defamed its soldiers.

India has suffered from an excess of the opposite. Even in the hands of someone as talented as my friend Vidhu Vinod Chopra (himself a Kashmiri). His muscularly “patriotic” Mission Kashmir launched a genre that had Kashmiri Muslims proving their “Indian” patriotism by collaborating with the Army. His bubbly Preity Zinta as Sufiya Pervez (remember that silly “Bumbro-Bumbro”) is a fantasy stereotype now challenged by the tragic, confused, sincere but helpless Arshia Lone (Shraddha Kapoor) in Haider.

She leads an ensemble that portrays the dilemma of the Kashmiri, Army soldier, local cop and, ultimately, Indian filmmaker. Kashmir lends itself easily to comparisons with Hamlet and his unending tragedies. Acknowledging these, rather than burying them under propaganda, does credit to a great democracy. Particularly at a time when the military challenge within the Valley is over, there’s been no combat against indigenous Kashmiri militants for a decade, and problems exist only on the LoC and across it.

Postscript: My last reporting visit to Kashmir was in 1990, for India Today. Edward (Ned) Desmond of Time magazine and I set up a visit to the LoC hoping to catch an Army ambush of infiltrators. The Army, home ministry, intelligence agencies were all helping. Naresh Chandra was then home secretary, his brother G.C. “Gary” Saxena (former RAW chief) was now Kashmir governor, and we were all set. We spent several nights in Uri on the LoC waiting, but nothing happened. Till a day after we had left, empty-handed, when the Army carried out a big ambush. One evening at a lonely outpost, Ned asked the commander how he explained India’s case on Kashmir to his soldiers. Were they not confused by rival propaganda, Kashmiri hostility? The officer said, don’t ask me, ask my troops. So we did.

This was a platoon of Grenadiers and our interlocutor, a Gujjar from deep Rajasthan, and still a young jawan yet to earn his first stripe.

“Hum toh kisaan ke bete hain, sir (we are sons of farmers),” he said. “It is no business of ours to check how our forefathers got the land we have inherited. If you want it, either you kill me, or I will kill you. Bahas kya karni hai, sir (what’s the point arguing?)”

The officer smiled. You can see why that conversation endures.

Also read: Haider to Shikara: Why Kashmiri Pandits are done being homeless and voiceless