Which side of the debate are you on over the online mocking of the new Union Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya’s proficiency with English?

One side objects to these attacks as ridiculous, unfair and pompous. For early disclosure, I am on this side. It brings back to me the famous — but now forgotten — words that the late Raj Narain spoke when visiting London as India’s health minister in the Morarji Desai/Janata Cabinet of 1977-79.

He was asked by journalists how he could run his ministry if he knew no English. Socialist Raj Narain, who we could describe as the original ‘Lalu Yadav’, was unfazed. “Arrey, sab angrezi jaante hain hum. Milton-Hilton sab padhe hain (We know all English. We have read everything from Milton to Hilton).” For the record, his rustic method and somewhat Rastafarian look belied his education. He had been a student union leader, a freedom fighter and Congress member at the age of 17.

He published a weekly newspaper called Janmukh from Varanasi. In Hindi, of course. His imperfections with English language didn’t stop him from defeating Indira Gandhi, not once but twice.

First, in the election petition at the Allahabad High Court that led to her imposing the Emergency. And then, when it was lifted and he returned from her jail, in their next electoral battle in Rae Bareli.

The other set sees Mandaviya’s old tweets in far-from-perfect English as riproariously funny, and also not just funny. How can he be trusted with the health ministry of India in an ongoing pandemic? But then, follows the argument, what better can you expect from Narendra Modi’s BJP? It demonstrates both, BJP’s talent deficit and couldn’t-care-less arrogance, and should remind India’s voters of the ‘blunder’ they made in voting for it.

The reason I am on the other side, as I believe most Indians would be, is that to conflate the knowledge of English with being educated, literate, intelligent or having intellect is wrong and supercilious. English doesn’t hurt, but what a minister or anyone in public life needs is political instinct, intelligence, ability to learn and the aura to build confidence within their team.

Today, nobody remembers that K. Kamaraj, the most powerful president of a national party (Congress, 1963-65) until Amit Shah rose in the BJP, had had to drop out of school at the age of 11 because of deep poverty and the death of his father. He knew his Tamil, the mind of India’s poor, and had the political instincts of a genius. His knowledge of English? Perhaps he was fortunate not to have lived in the Twitter era.

And, finally, there is our deep-set social elitism that cuts across trades and professions. We saw some of this when Manohar Parrikar, as defence minister, would strut around in chappals at stiff armed forces’ ceremonies. India should have known better than this. Two of our most successful defence ministers, Y.B. Chavan and Babu Jagjivan Ram, had the most un-military-like demeanour and disposition. But we in India don’t know our own political history.

Also Read: Why have Modi’s rivals failed to challenge him? This survey of Indians’ religiosity has clues

We cannot underestimate the importance of knowing English. In India, it is the language of empowerment. That’s why the Lohiaites were wrong in packaging their opposition to social elitism as a rejection of English. Mulayam Singh Yadav tried perpetuating this in Uttar Pradesh, but his son Akhilesh wisely made a quiet departure. That is the reason now that chief ministers like Yogi Adityanath and Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy are prudent to push for English-medium education. What is wrong is to mock people who aren’t so proficient in the language as illiterate or ganwaar (rustic).

We Indians have also adopted English to our own ways of speaking, writing and even interpreting. Robin Raphel, when she was US Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia, would tell us the story of how after Pranab Mukherjee had concluded his visit to Washington (when P.V. Narasimha Rao was PM), one of her fellow American interlocutors asked her to explain a few things he had said in his famed Bangla-accented English. After she had explained, she said, the person told her, “Hey Robin, these Indians of yours, they speak 16 dialects of English language.”

It isn’t just the diction. We also write and use the language in different ways across the country and I have tried picking up the nuances in my travels. The first time I went to the northeast, as a reporter for The Indian Express in 1981, several important opinion-makers I met would advise me against trusting so-and-so because “he’s a troubleshooter”. Now I might have thought a troubleshooter is actually a good guy. But, in the Brahmaputra Valley, it was synonymous with troublemaker. In Bengal, you ask where is so-and-so, and you might hear they’ve “gone marketing”. That’s local English for shopping.

In most of small-town Punjab, people might be unimpressed if you said you were an editor. Unless, realisation dawns: Oh, auditor. And then the face glows in appreciation. We live large-heartedly with jokes like King’s English and Singh’s English. This, by the way, was the headline of a ‘middle’ article that the late Prem Bhatia wrote in the late 1970s when he edited The Tribune.

Again, this is not to say it is better to use bad English. It helps to be correct, and intelligible. But it doesn’t mean that you are a good-for-nothing if you can’t. Also, what is perfect or correct English can be defined in a hundred ways depending on where you came from and where you learnt it. You could be near-perfect especially if, to borrow that line from Delhi’s matrimonial ads for brides, ‘Convented’. Or better still a ‘Tharoorian’.

Not everybody learnt English early in school. How you relate to the language also depends on how you learnt it. I spent almost all of my early schooling years in a system where the teaching of the English alphabet began from Class 6. And then there were some speed-learning tricks like the convenient and fun doggerels teachers would confect to teach you some vocabulary. Sample from Punjab: Pigeon-kabutar, udaan-fly/look-dekho, asmaan-sky/beti-daughter, paani-water/jai hind-namaste, hello hi. Of course, everything pronounced native style “falayee, sakayee, daater” and “waatar” etc. Isn’t it better than a boring primer that begins by presuming you are illiterate in the language?

Also Read: Can 2024 become more challenging for Modi? Yes, but it’s all up to Congress

We learnt English from the newspapers, radio bulletins and, most importantly, cricket commentary and improved over time. We, the Hindi Medium Types or HMTs as I call us, never became perfect with the language, either spoken or written. But we got by as India changed.

This is the month of the 30th anniversary of economic reforms. Critics on the Left attack reforms for unleashing a new wave of elitism in India. But they are wrong. Most of them are, in fact, scions of the entitled old elites who got greatly outnumbered, outranked and, cruelly, out-famed by the new generations of HMT Indians empowered by the economic boom.

Suddenly, there were so many companies, employers and the need for skilled workers exploded. There was no way the Doon Schools, St Stephen’s Colleges, Oxford, Cambridge, the entire Ivy League could fill this need. Suddenly, it wasn’t so important who your daddy was, whether your college held jam sessions, or which club your family was members of. This change spread across the board, from corporate board C-suites to start-ups, civil services, and that last fortress of Anglophile elitism, the armed forces.

At which point I might be reminded to step back from this sociological digression and return to my home turf, which is politics, and what the Mandaviya controversy teaches us about it. Also, where I’ve been flawed in my own understanding and analysis of the Modi phenomenon. For some time now, I have maintained that his political proposition has three key elements: A new, redefined Hinduised nationalism, image of an anti-corruption warrior and efficient delivery of welfare to the poorest.

I had overlooked another key factor: Anti-elitism. Over the decades, a popular revolt has built up against English-speaking elites. Our school textbooks mentioned with pride the riches Nehru was brought up in. It doesn’t impress anyone now. But the ‘chaiwala’ story works.

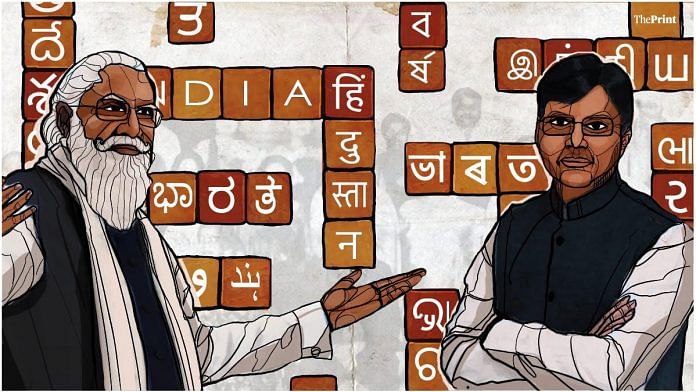

Modi is seen as the antithesis of what the Congress leaders have been. A desi versus Westernised elites. When he attacks Lutyens’ and Khan Market ‘gangs’, it is a code for this upper crust which, he tells his voters, ‘has been in power for far too long, and undeservedly so’. That’s why when you mock him for spelling strength as ‘streanh’ or Mansukh Mandaviya for calling Mahatma Gandhi ‘nation of the father’, you make his point to his voters.

Also Read: Remembering a Haryana girl who made Hindi Medium Type cool by becoming a heroic astronaut