If I were to indulge myself with just that one National Interest about cricket with the World Cup on in India, this is the best time for it. Because once the Cup is won or lost, there will be 1.43 billion opinions and the real gyanis will talk. This week, however, I will talk about cricket and also kabaddi — with a garnish of football thrown in. So be warned.

I am also talking mostly not about cricket. It’s about much else that emanates from it. Nationalism, politics, emotion, you take your pick. I’d pick all three.

With just a few games remaining before the knockouts, we’ve seen upsets and the odd close game, but have you noticed how cordial and friendly the encounters have been? Almost no words exchanged between players, mostly just a lot of smiles.

A few shrugs now and then, frowns, unhappiness at umpiring, shouts of disapproval when a fellow fielder messes up. But among themselves, the players have been sporting, even good-humoured. Never mind some controversies, the most prominent being the crowd at Ahmedabad’s Narendra Modi Stadium during the India-Pakistan match. The important thing is, the players have stayed out of it.

The Pakistanis have provided entertainment on the side, some funny, some not quite so. All of it, however, is at the cost of their own team. However their team might perform finally, if there were two more medals on the side for the best memes and the most rollicking sense of humour in the course of this World Cup, the Pakistanis would have no competition. Abuse, if anything, is directed entirely at their own Board, and sometimes, unfortunately, at some players.

That said, we return to the three aspects from this great six-week event we posited for discussion this week: nationalism, politics and emotion. Why has this been such a good-humoured tournament? There have been great successes, disappointments, upsets, misses, umpiring complaints, but among the players it’s an outbreak of peace you wouldn’t expect in an international event of such intensity.

International cricket has in fact followed this course for some time. India played a purely cricketing role in triggering that change. The momentum of Steve Waugh’s all-conquering Australian epoch was broken by Sourav Ganguly’s challengers, who also established a balance of power in the game — and in sledging. The Aussies haven’t been quite like that since and, generally, the cricket field has calmed down.

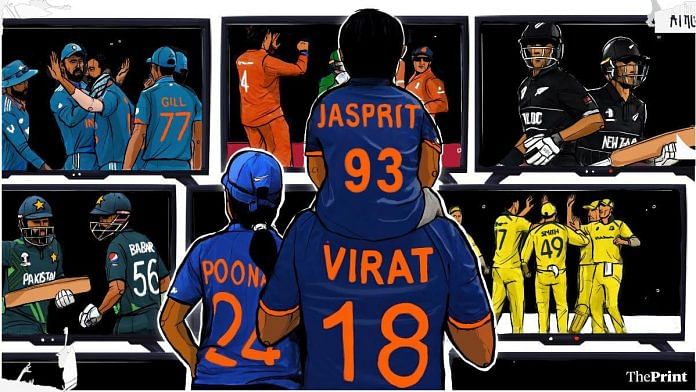

This isn’t to say there is no display of emotion or disagreement — there’s been much, including ball tampering. Overall, however, among rival players, relationships have improved. Before the India-Pakistan match, for example, Shaheen Shah Afridi congratulated Jasprit Bumrah on the birth of his child — a compliment from one top pacer to another.

Pakistan captain Babar Azam had Virat Kohli publicly, and on camera, sign an India shirt for a nephew. So calm have things looked that it has caused some old-timers consternation. If Babar really wanted that shirt for his nephew, said former Pakistani great Wasim Akram (now a star commentator), he should have done it in the dressing room, not in public. While he was obviously hurting after the loss, and thought that such cordiality took away his team’s intensity, he does not understand how the nature of cricketing rivalries has changed from his era.

Also Read: We are cricket-crazy and partisan, not Nazis. Stop demonising Gujarat crowd

To understand this change better, I have to take you from cricket to kabaddi. What do names like Amir Hossein Bastami, Mohammedreza Kaboudrahangi, Milad Jabbari and Vahid Rezaeimehr mean to you? None of these is a cricketer, you’d know. These sound like names from Iran, where cricket isn’t played, at least not competitively. These are, however, among the most popular Iranian kabaddi stars.

To understand why we’ve dragged them into what looked like a discussion on the Cricket World Cup, I have to take you back to the India-Iran kabaddi final (for gold and silver medals) at the Hangzhou Asian Games just 28 days ago. If you didn’t watch that incredible game, do so now and it will help you understand this argument about sport and nationalism, politics and emotion.

With just one-and-a-half minutes to go, the teams were tied 28-28. Indian captain Pawan Sehrawat went in for a do-or-die raid. He, by the way, is the greatest superstar in the kabaddi world. He had an Iranian defender stray out of the field, thereby winning a point, but while escaping was caught in a melee of defenders.

The umpire was unsure what to do. Should he penalise the attacker as well as the five defenders so it would be 5-1 — and therefore make it 33-29 points in favour of India — or make it just 1-1 or 29-29? The twist was that in amateur kabaddi, the rule would have given India 5-1. But under the new rules followed by the Pro Kabaddi League — the game’s equivalent of the IPL, also owned by India — the score would’ve been 1-1. The dispute held up the gold-medal game for almost an hour.

The Iraqi referee came in, pronounced in favour of Iran, and grandly stated that “this is the rule I’ve been teaching kids all my life”. The Pakistani secretary-general of the Asian Kabaddi Federation endorsed him. The Indian captain and coach kept arguing, as did just a couple of Iranians, but all in a perfectly civil manner.

The rest of the players sat on the pitch, with calm you’d never expect from top competitors when the gold is at stake. They waited as the jury met, and its Kenyan head — a woman, Laventer Oguta — ruled in favour of India. No protests, no abuse, no throwing of things. Of course, the Sportstar article by Lavanya Lakshmi Narayanan from which I take this detail also noted that the Iranians wore their silver medals like albatrosses around their necks.

Now return with me to the Iranian names listed earlier. These are only four of the 13 Iranian stars who came in to play in the last Pro Kabaddi League for different Indian franchises: Puneri Paltan, Tamil Thalaivas, Telugu Titans, U Mumba, UP Yoddhas and so on. Both the Indian and Iranian players were now competing for national glory. But in club kabaddi, there were often teammates. There was too much familiarity and camaraderie for anything ugly now.

To understand this better, let me share some numbers. Besides the 13 Iranians, Kenya, Taiwan, England, Sri Lanka, Poland, Iraq, Nepal and Bangladesh also had players in the Pro Kabaddi League.

Also Read: How boorish treatment of Kohli by Ganguly’s BCCI takes Indian cricket back to an inglorious past

Exactly this has been happening to international cricket for 15 years now, since the IPL began. It spawned similar leagues in many other countries, including Pakistan. The players who face each other for their national teams are also often teammates in franchises. In any case, there is much travel and sharing, and friendships develop over time as well. It is these relationships that, even if they can’t transcend the boundaries of nationalism and political differences among their countries, greatly smoothen their emotions.

Indians and Pakistanis may not be playing in each other’s leagues, but check out the rest. Thirteen current Aussie and English players have come to the IPL. Add to this 12 New Zealanders, seven South Africans, seven Afghans, four Sri Lankans, three Bangladeshis, even one from the Netherlands. Many of them will also play in the leagues elsewhere. When you spend so much time together, especially as club/franchise teammates, it does have a healing effect.

We have seen this over the decades with football, with club loyalties and professionalism softening hard nationalism. I wrote a National Interest making a similar point in June 2000, inspired by watching Euro 2000. Much of that is playing out in cricket now.

The reason we brought in kabaddi is precisely because it explains the change even better. If these edges can be smoothened even in a purely physical contact sport, why not in relatively genteel cricket? That the home of the top leagues in both the games is India doesn’t hurt.

Also Read: Caste, ethnicity, religion – United colours of Indian hockey prove the game thrives in inclusivity