Over the past month, the Indian rupee has depreciated due to foreign portfolio outflows, broad-based dollar strength and concerns about weak corporate sector performance.

Donald Trump’s victory in the US opens the door for higher tariffs, stronger dollar and higher bond yields—all contributing to a weaker rupee, at least in the short-run.

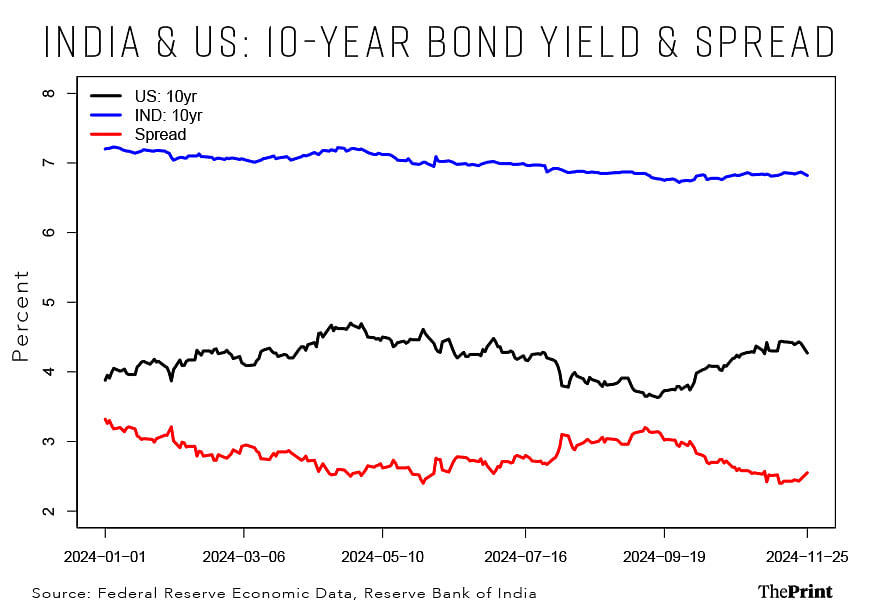

Broad-based strength of US dollar & spike in US bond yields

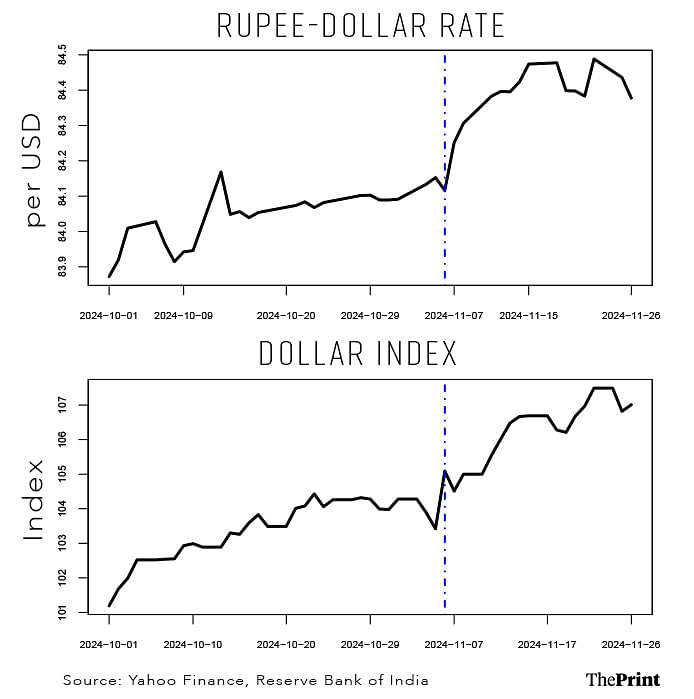

The US dollar has rallied in the weeks since Trump won the presidential election. The dollar has risen on the expectation that Trump’s proposed policies could fuel inflation and delay rate cuts.

Trump’s willingness to cut taxes, curb illegal immigration and impose significant tariffs on foreign imports could likely exacerbate inflation. Coupled with an already elevated debt level, Trump’s policies could prompt the Federal Reserve to put brakes on its rate cut cycle.

With fiscal discipline taking a back seat, investors demand higher yield for holding US bonds, resulting in fall in bond prices and rise in bond yields. Trump’s policies may bolster growth in the US in the short-term, providing strength to the dollar.

US corporate performance has also given a boost to the dollar. Most of the S&P 500 companies reported solid earnings in the July-September quarter. The robust corporate performance has improved the outlook for the US economy, attracting global capital.

Rise in US bond yields and the dollar index have dented currencies in the emerging markets. The narrowing differential between the Indian and US 10-year bond has triggered foreign fund outflows from emerging markets, including India.

Since the beginning of November, the rupee has weakened nearly 0.3-0.4 percent. To be sure, a rise in currency volatility was seen in the run-up to the elections as well.

FPI outflows

The rupee has been under pressure due to sustained foreign portfolio investment (FPI) outflows over the last two months. After being net buyers in the Indian capital market for four months (June to September), FPIs turned net sellers in October. The selling spree has continued in November as well.

While the continuing geopolitical uncertainty, concerns over sluggish corporate performance and the likelihood of a weaker GDP growth in Q2 led to sell-off by foreign investors, the recent Adani fiasco has impacted the broader market sentiments and exacerbated FPI outflows.

The possibility of a short-term boost to growth following Trump’s victory and the relative attractiveness of China in the aftermath of the recent stimulus measures have also impacted FPI flows and weakened the rupee. To be sure, the intensity of FPI sell-off has tapered in the last few days of November. The major concerns are the subdued corporate earnings and weakness in growth. If these trends are reversed, FPI flows could see a rise.

RBI’s actions to limit the rupee’s slide

In the past few years, particularly since late 2022, the Reserve Bank of India has actively intervened in the currency market to ensure rupee stability. While the intervention data is available till September, change in reserves can be considered as a crude proxy for intervention.

Data shows that after surging to a record USD 704 billion by September-end, foreign exchange reserves have been recording a decline. As of 15 November, foreign exchange reserves hit a four-month low of USD 657.89 billion.

The fall in reserves is triggered, in part by the RBI’s intervention in the forex market to limit the rupee’s fall. Revaluation losses also contributed to a decline in foreign currency assets. Trump’s victory bolstered the dollar and the US bond yields, leading to revaluation losses.

Intervention by the RBI likely limited the rupee’s losses. From 1 November to 26 November, while the dollar strengthened by 2.6 percent, the rupee weakened by 0.34 percent during the same period.

In addition to intervening in the foreign exchange market, the RBI has been reportedly using its regulatory powers to limit the rupee slide. The central bank has reportedly instructed banks to cut their long position in the rupee-dollar pair in an attempt to lower the demand for dollars.

On previous occasions, the RBI had reportedly stopped banks from adding long positions on the dollar-rupee pair. It is debatable whether such an expansion of regulatory powers is desirable to stem the rupee slide, as this could distort the incentive structure and the cost of doing business.

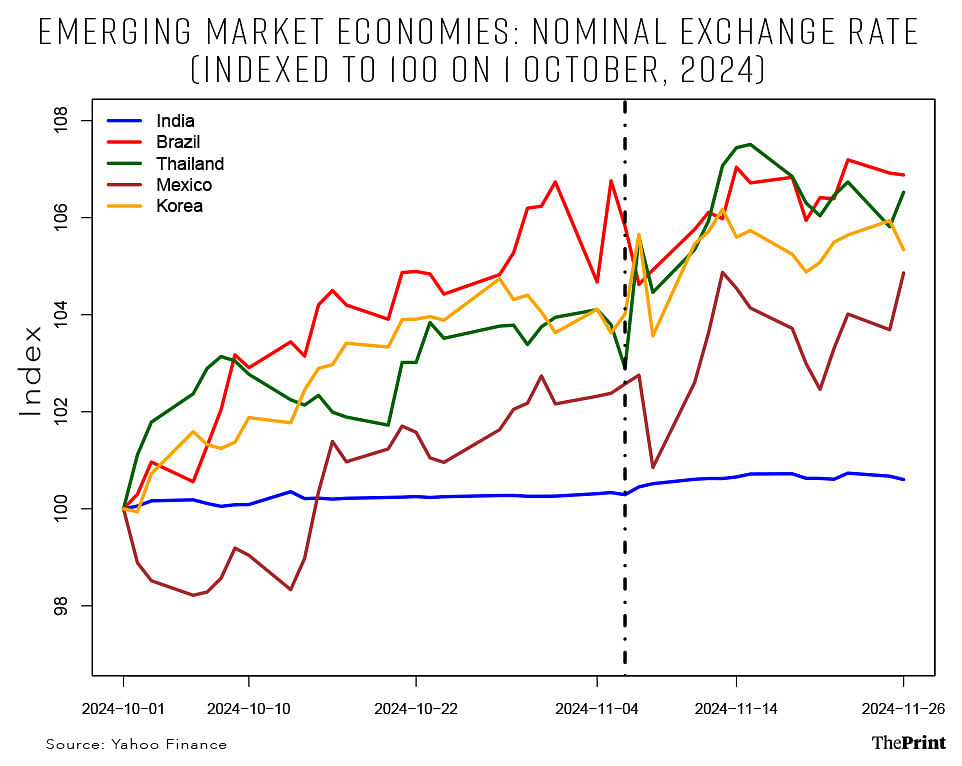

Rupee depreciation mild compared to emerging market peers

The pace of rupee depreciation has been mild, compared to some of the other emerging market economies. To some extent, the RBI’s actions have prevented a sharp slide of the rupee. But there are other factors also at play.

The Brazilian real, for example, has witnessed a much sharper depreciation as Trump’s policies are likely to have an adverse impact on exports, such as steel, automobiles and other industrial goods.

Mexican currency has also faced strong depreciation as Trump has promised to impose high tariffs to pressure the Mexican government to curb immigration and drug flows across the border. Thailand’s reliance on trade with China and the US has led to its currency’s depreciation in recent days.

Radhika Pandey is associate professor and Madhur Mehta is a research fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP).

Views are personal.