New Delhi: The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, brought in 13 years ago as a stringent law to shield minors from sexual predators, is now being seen as one that is being weaponised to criminalise adolescent love.

This is the crux of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL), in response to which the Supreme Court is examining whether the age of consent under POCSO should be brought down from 18 to 16 years.

While the Centre is opposed to this change, senior advocate and amicus curiae Indira Jaising has urged the court to lower the age of consent, arguing that POCSO unfairly criminalises consensual relationships between teenagers.

She cited a sharp rise in POCSO cases involving adolescents and recommended a “close-in-age” exception to protect such relationships from prosecution.

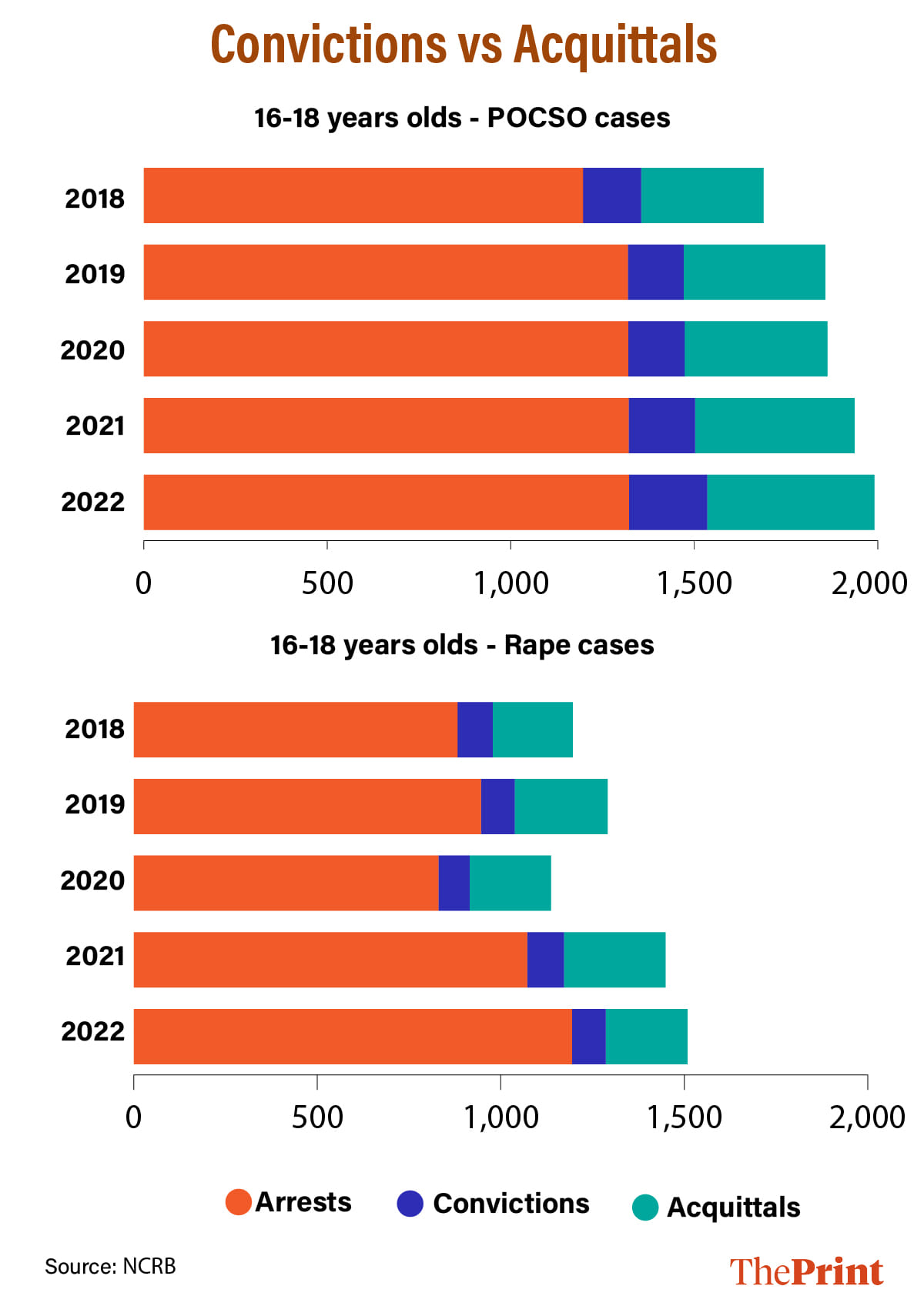

The numbers paint a concerning picture. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data for the period 2018-2022 shows a steady increase in arrests of juveniles in the 16 to 18 age group under POCSO, while the acquittal rate continues to be higher than the conviction rate.

The conviction rate has hovered between 11 and 12 percent—from 12.22 percent in 2018 to 11.18 percent in 2022—showing no significant improvement despite rising arrests. This data was submitted by the Centre to the top court in response to the PIL filed by Advocate Nipun Saxena.

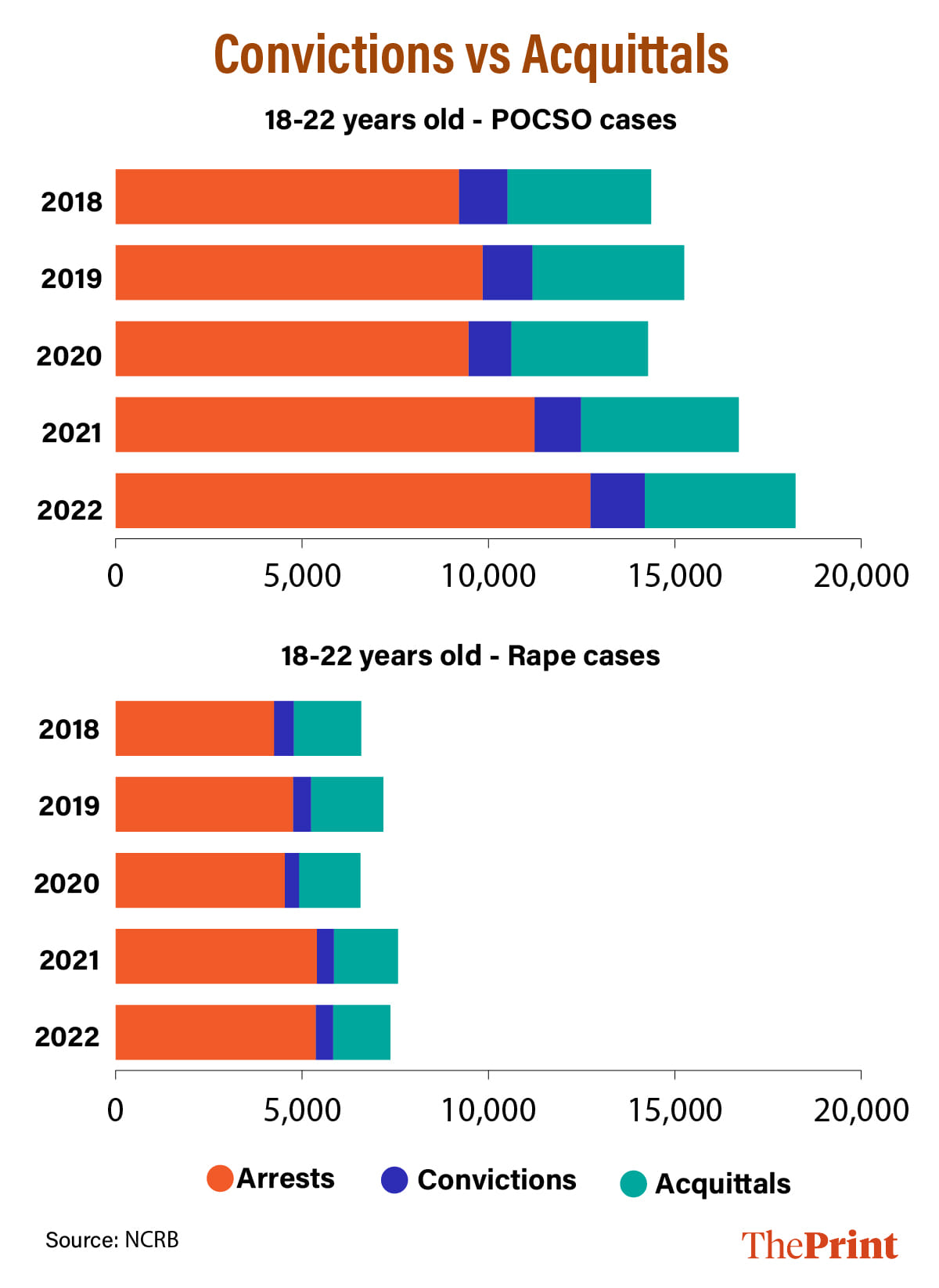

This NCRB data covers arrests, convictions and acquittals in POCSO as well as rape cases in trial courts while specifically focusing on two age groups—juveniles aged 16-18 years and young adults aged 18-22 years.

A total of 6,892 juveniles aged 16 to 18 were apprehended under POCSO and 4,924 juveniles under the erstwhile Indian Penal Code (IPC). Taken together, 11,816 juveniles were booked under serious sexual offence charges in the five-year period.

Of these, 855 juveniles were convicted under the POCSO Act and 468 under IPC rape provisions, totalling 1,323 convictions—thus amounting to a conviction rate of 11.2 percent.

New NCRB data also shows that a majority of accused youth—especially those aged 18 to 22—are acquitted in sexual offence cases. The conviction-to-acquittal ratio remains below 0.4 percent across both in rape and POCSO cases in this group.

The data from 2018 to 2022 shows a steady increase in the number of juveniles (aged 16 to 18) apprehended in sexual offence cases under both the POCSO Act and IPC. In 2018, the number of juveniles apprehended was 2,079, which gradually rose each year and reached 2,728 in 2022. This reflects a 31.2 percent increase in juvenile apprehensions over the five-year period.

This suggests a considerable gap between legislative intent to protect children and the practical realities of the justice delivery system.

Also read: SC convicted POCSO accused, then set him free—it factored in lived realities & systemic failures

What the law says

Under the IPC, Section 375 defined rape as non-consensual sexual intercourse by a man with a woman, with punishments under Section 376 ranging from 10 years to life imprisonment.

These provisions have been retained in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, under Sections 63 and 64, which continue to treat rape as a gender-specific offence and carry similar sentencing guidelines.

The POCSO Act of 2012 is a special law aimed at safeguarding children below 18 years from sexual abuse. It criminalises all forms of sexual activity with minors, regardless of consent. Sections 4 and 6 deal with penetrative and aggravated penetrative sexual assault, often attracting stringent punishments.

Centre’s opposition

Amicus curiae Indira Jaising has submitted that blanket criminalisation infringes upon the constitutional rights of teenagers to “personal autonomy and dignity”, and lacks “empirical” or rational justification.

The Union Government, however, opposed any change, stated that the age of consent at 18 is based on clear legislative intent and constitutional protection. It warned that reducing the threshold could increase the risk of exploitation and weaken safeguards meant for minors, while pointing out that courts already have discretion in exceptional cases.

In its affidavit, the Union Government stated that “any dilution of the current framework may defeat the very object of the POCSO Act, which was enacted to provide robust safeguards to children against sexual exploitation and abuse.

Rise in apprehensions and convictions of juveniles

In the 16 to 18 age bracket, a total of 6,892 juveniles were apprehended under the POCSO Act during 2018 to 2022. Of these, a total of 855 were convicted. The number of such convictions increased year-on-year, reaching 213 in 2022, from 116 in 2018—a rise of 83.9 percent in five years.

Most of these convictions resulted in sentences of up to 10 years, with only a small number receiving life imprisonment or capital punishment.

In rape cases under IPC involving juveniles, 4,731 cases were recorded, with 4,924 apprehensions and 468 convictions between 2018 and 2022. Again, the data shows that sentencing largely fell within the 10-year range.

POCSO & kidnapping

Swagata Raha, director of research at Enfold India, a non-profit organisation working on issues related to gender-based violence and child sexual abuse in the country, told ThePrint, that the Centre needs to look at the correlation between the provisions of POCSO and kidnapping.

“Anecdotally and on the field, we see that many of these cases involve the girl leaving home. The case is initially filed as a missing person complaint. It is only after the parties are located and there’s a statement that the police records or the girl is taken for a medical test that POCSO charges get attracted. At this stage, it is hard to say whether it is consensual or not. And usually when the girl goes in front of the magistrate, that is when she says that this (the relationship) was entirely consensual or she comes to the court and says it,” she said.

About juvenile apprehensions, she said, “One might say it shows criminality, but it could also be that more and more young people are being criminalised because it could easily be a romantic case.”

High rate of hostility in juvenile cases

The data also reveals significant challenges in prosecution due to witness and victim hostility. For juveniles (16 to 18 years) in rape cases, a total of 1,050 cases were recorded where victims or witnesses turned hostile. In these specific cases, there were 786 acquittals, 174 convictions and 90 ‘accused’ were discharged.

In POCSO cases involving juveniles, the issue was even more pronounced, with 2,143 cases seeing hostile witnesses. These instances led to 1,684 acquittals, 113 discharges, and 349 convictions.

In the young adults group, the numbers are significantly higher—indicating a high volume of cases and acquittals. A total of 49,533 POCSO cases were registered during the period, with 52,471 persons apprehended under the Act. Of these, 6,093 were convicted.

In rape cases under IPC involving this group, 22,663 cases were recorded, with 24,306 persons apprehended and 2,585 convicted.

In terms of sentencing, most of those convicted in this age bracket were sentenced to up to 10 years in prison, similar to the juvenile group. The data shows a relatively low number of sentences exceeding 10 years, with very few getting life sentences or capital punishment.

However, witness hostility remains a major hurdle. A total of 17,340 POCSO cases involving the young adults age group reported hostile witnesses. Of these, 14,904 resulted in acquittals, 542 in discharges, and 1,894 in convictions.

In rape cases under IPC, 6,499 cases reported hostile witnesses, leading to 5,321 acquittals, 347 discharges, and 832 convictions.

Swagata Raha simplifies, “There are chances of victims turning hostile because that is the fate of most cases of rape and sexual violence because of the kind of taboo, pressure and influence. But here the pattern is different. Through various studies it has emerged that at the magistrate level itself, the girl will start saying that this is consensual or my parents were arranging a marriage and I decided to run away. Here, the girl is saying that the relationship is consensual at all stages of the legal process.”

Conviction to acquittal ratios show low success

The conviction-to-acquittal ratios across both crime heads and age groups indicate a significant challenge in securing convictions. For every one acquittal, there is generally less than half a conviction. This shows how often prosecutions result in convictions versus acquittals.

The conviction-to-acquittal ratios remain low across both age groups and both laws. For juveniles in IPC rape cases, the ratio is approximately 0.45 convictions per acquittal.

In POCSO cases, the figure drops to around 0.4. Among young adults aged 18 to 22, in IPC cases, the conviction-to-acquittal ratio is around 0.4, while the lowest ratio—approximately 0.35—is seen in POCSO cases.

These figures highlight a persistent pattern where acquittals significantly outnumber convictions in cases involving sexual offences against minors.

Among the most striking revelations is the sheer volume of cases involving young adults under 22 years—over 49,000 POCSO cases and nearly 23,000 rape cases were registered involving this group over five years. Of these, a considerable number of cases involved juveniles aged 16 to 18, the very group under consideration for relaxed legal treatment.

Speaking about the high acquittal rate, Raha explains, “The data on high acquittal rates tells us victims are not supporting the case of the prosecution. It tells us that the prosecution is not able to discharge the burden that is on it. Or victims do not want to implicate the accused, or there is influence and threat.

“Based on our latest study of 264 cases of aggravated penetrative sexual assault against children, girls’ testimonies against the accused were an exception in ‘romantic cases’ and was seen in only six ‘romantic’ cases (9.0%), whereas in the majority of cases, i.e., 60 cases (89.6%), they did not incriminate the accused. It was also seen that the rate of testimony against the accused was significantly lower in ‘romantic’ cases, as compared to other cases, i.e., girls testified against the accused in 36% cases which were not expressly ‘romantic’ in nature,” she said.

Young adults (18 to 22 years) face most arrests

The data unequivocally shows that most arrests are in the group of young adults aged 18 to 22. Over the five-year period (2018–2022), a total of 76,777 individuals aged 18 to 22 were arrested under rape and POCSO Act offences. This includes 31.6% arrests under IPC rape provisions and 68.4% under the POCSO Act.

In comparison, 11,816 juveniles aged 16 to18 were apprehended for similar offences, comprising 41.7% under IPC rape, and 58.3% under POCSO. This stark difference indicates that while both age groups are implicated in these crimes, the older demographic within the specified range accounts for the vast majority of arrests.

Deeper look into conviction-to-acquittal ratio among juveniles

The analysis of the five-year period (2018-2022) reveals a clear picture of how cases involving sexual offences against minors are progressing through the justice system.

Between 2018 and 2022, juvenile apprehensions in sexual offence cases saw a steady rise, growing from just over 2,000 to nearly 2,730. While convictions also increased during this period, they remained consistently lower than acquittals.

The conviction rate for both groups hovered between 10 percent and 12 percent, with only slight year-on-year variations. The conviction-to-acquittal ratio stayed below 0.5 throughout, reflecting a broader trend of prosecutions failing to result in convictions. Meaning that roughly only one in ten arrests leads to a conviction.

Even as more juveniles were brought into the criminal justice system each year, the outcomes rarely led to guilty verdicts.

The consistently low conviction-to-acquittal ratios, where acquittals outnumber convictions by more than 2:1, are a recurring theme.

In a conversation with ThePrint, Swagata Raha explains how it is not a debate between overprotecting them or not protecting them at all. Rather, she says, there has to be a balance that has to be found in law where protection is extended to those who are saying it is non-consensual. “And, to those who are saying that it is consensual and their age is above 16 years, then what they have to say has to be respected. At the moment, the law does not recognise it at all and it is causing more harm,” she added.

‘Protection vs criminalisation: A balance is beeded’

Several lawyers ThePrint spoke to, who did not wish to be named, supported the idea of lowering the age of consent from 18 to 16. They pointed out that the current legal framework often conflates consensual adolescent relationships with exploitative conduct, leading to the unnecessary criminalisation of young boys—especially from marginalised backgrounds. In many such cases, FIRs are lodged by disapproving parents after the girl elopes or enters a consensual relationship, regardless of her agency or willingness.

About finding the middle ground and balance between overprotection and criminalisation, Raha believes that we have to acknowledge whether “criminalising expression of sexuality at an age where it is developmentally normal affects their dignity and liberty”.

“Right now we have a problem with a 16-year-old with a 25-year-old; that same girl when she turns 18, can decide to be with a 40 to 50-year-old and no court of law can keep them apart,” she adds.

She says that currently, “it is a blanket solution, we are looking at everything as rape. It is not case to case. At some level we want the law to empower people to report the case to us instead of taking over their life.”

Delhi High Court senior advocate H.S. Phoolka, who is also appearing for a child rights organisation ‘Bachpan Bachao Andolan’, opposing the plea to decrease the age of consent from 18 to 16 pending before another bench, suggests a middle ground. In a conversation with ThePrint, Phoolka suggests that instead of a “blanket law on the age of consent, the courts should be empowered to deal with these matters on a case-to-case basis”.

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: POCSO law must protect, not punish young people for consensual relationships

POCSO, while brought up too heinous crimes against children, has turned into national disaster. A rampant misuse is of POCSO is a national social safety issue. This article deals with only teenage love part of the issue. There is also an issue where POCSO is being used to score the personal revenge by neighbors, relatives, etc. In the process, lawyers, police, and so called social servants making the money. Please investigate this as well.

Not just POCSO, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) Sections 63 and 64 (dealing with “rape”) must be repealed at the earliest. These laws are just tools for women to harass and intimidate men. Every sexual act in the world is consensual. There is nothing called as “acting against consent”. These things are just conjured up by idiots like Indira Jaisingh to further the feminist cause of labelling innocent men as criminals.