New Delhi: The Indian Rupee has depreciated by about Rs 9 per dollar since the beginning of 2022, falling from about Rs 74 in January this year to Rs 83 in October. While conventional economics would suggest that a depreciating rupee should be good news for the country’s exporters, this does not, in fact, seem to be the case in the real world, as shown not only by trade data but also the testimonies of industry players.

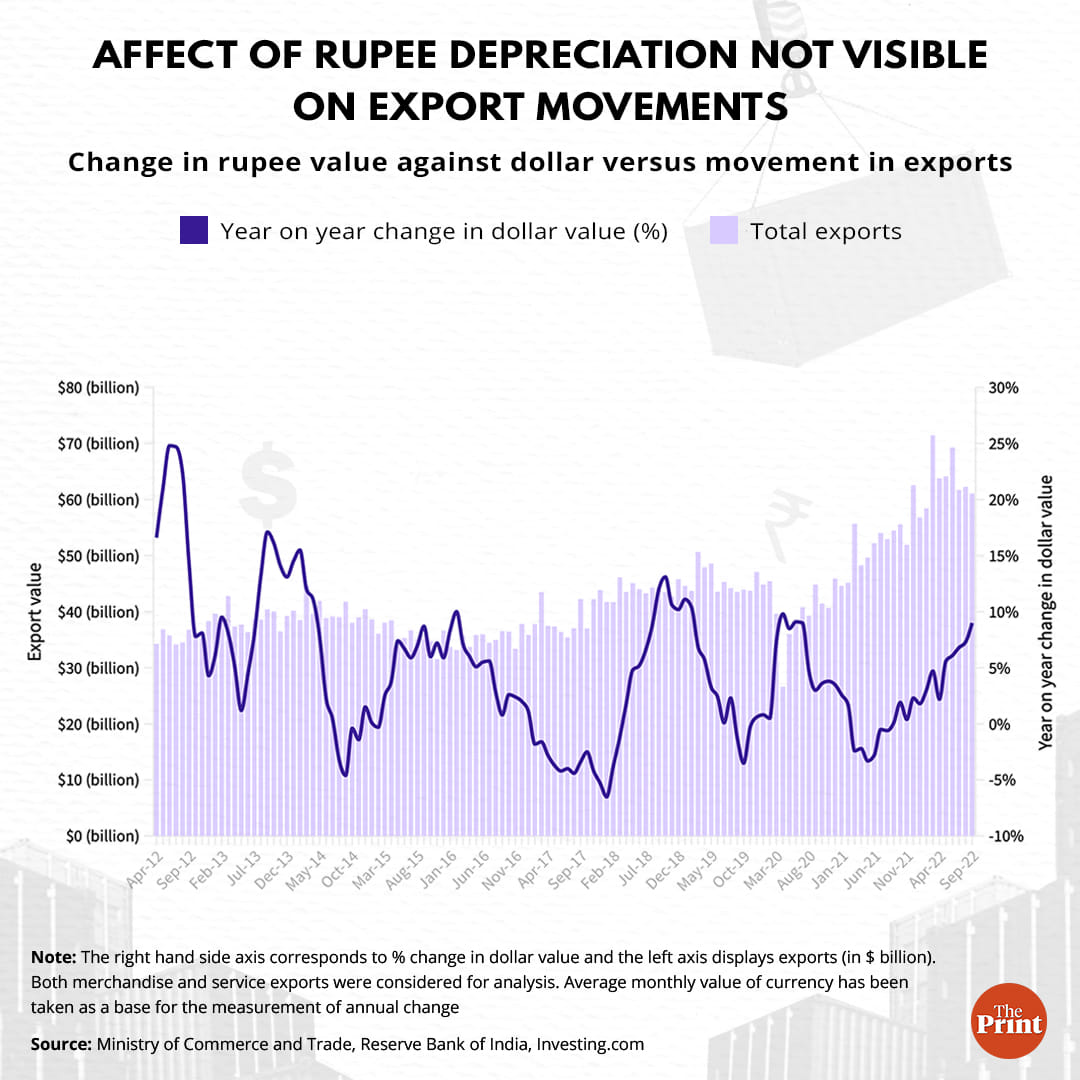

ThePrint analysed 126 months worth of trade and foreign exchange data from April 2012 till September 2022, and spoke to exporters’ bodies and industry players to understand the relationship between the rupee value and India’s export performance.

Both the data and the inputs from the industry players show that the rupee’s exchange rate actually has a negligible impact on India’s export performance.

This goes against conventional understanding since, when the rupee depreciates, it means a dollar can buy more goods and services from India. In other words, imports from India become cheaper for the country’s customers abroad who pay in dollars. But exporters’ bodies in India have told ThePrint that things aren’t as simple.

Ajay Sahai, Director General and CEO of the Federation of Indian Exports Organisation (FIEO), an exporters’ body recognised by the government of India’s export promotion councils, says that while there are multiple factors affecting export performance, currency isn’t a strong one.

“India’s exports are generally commensurate with the global trends in trade. When the global exports go up, India’s exports also grow and at times with better speed. Currency value does play a role but not significant enough to cause substantial shifts in exports,” he said.

Also Read: Indians cut down on milk purchases or switch to cheaper options as price rise, finds survey

Weak Correlation

This weak relationship between the exchange rate and exports is backed by the data.

ThePrint took the year-on-year change in the average monthly value of the dollar in terms of the rupee (Rs per dollar) and checked it with the corresponding month’s exports figures. The data shows that the relationship between the two is weak. In fact, the data shows that even imports do not exhibit any pattern corresponding to currency fluctuations.

The coefficient of correlation, a measure of the strength of the interdependence between the annual percentage changes of average currency movements and exports was -0.3, establishing a weak relationship between the two.

The coefficient of correlation is used to define the magnitude of a relationship between two independent events. It can range between -1 and 1, with -1 implying a very strong but inverse relationship, while a reading of 1 implies a strong positive correlation. A correlation coefficient at or near zero implies there is either no correlation or a weak one.

What a correlation coefficient of -0.3 simply means is that a movement in the currency value does not exhibit any significant impact on exports. Often, exports have moved in ways that belie the conventional rupee-export dynamics. That is, sometimes, when the rupee has depreciated significantly, India’s exports have fallen. Other times, when the rupee has appreciated strongly, exports have surged.

Also Read: More bad news after inflation hits 5-month high: Wheat stocks at 6-yr low, ‘rice output to fall’

Other Factors At Play

Sahai further explained that a depreciating currency has consequences for export industries that have to rely on imported inputs from other countries.

“A depreciating rupee means that importers will have to shell more rupees in order to get the same product,” he said. “For exporters who have to import input goods, the increased cost actually nullifies the gains they could have made from currency depreciation. Further, currencies across the world are depreciating, and not just the rupee, so the competitive advantage of devalued currency is also ruled out.”

Another factor that affects the performance of the export-oriented sector is inflation, industry players say.

SK Saraf, chairman of the Technocraft Industries India Limited, a company exporting industrial goods from India said that there is “hardly any relationship” between exports and a depreciated currency.

“Even if the rupee depreciates by 10%, the exporters may gain only by upto 0.1 – 0.3% that too depending on the circumstances. The potential of gaining from depreciating currency is lost out on higher inflation. Then, the customers also start asking for discounts. Hence, the exporters generally do not gain much when currency depreciates,” he added.

Rajeswari Sengupta, associate professor of Economics at Mumbai-based policy research centre, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR) said that the relatively weak relationship between the exchange rate and export performance might also be a result of a delay in the transmission of the benefits of a depreciating rupee.

“I don’t think that exports respond to exchange rate changes within the same month. The lags are much longer,” she said, adding that the international prices of commodities also play a crucial role in determining the direction of trade.

“For example, when commodity prices are high, petroleum and metals exports will increase, which may lead to an appreciation of the rupee (as in the mid-2000s),” she explained. “So, then, you would see an inverse correlation between exports and depreciation. These factors (and some others) mean that one needs to do a careful econometric analysis. A simple correlation will not show the relationship.”

Besides time lags and commodity prices, Rajeswari also says that trade movements involve “immense institutional complexity”.

“It takes a long time to build relations in international trade and gain trust and credibility and then to participate in the global production chain,” she said. “Once the production and exporting process takes off, everyone would be reluctant to rock the boat. This would tend to drive down the short-term impact of USD-INR changes.”

(Edited by Anumeha Saxena)

Also Read: Russia-Ukraine war, prior orders, new importers — why India’s wheat exports ‘doubled’ despite ban