New Delhi: Swastika Jajoo wasn’t sure if her grandfather was going to make it. At 86, he was admitted to Aurangabad’s Kamal Nayan Bajaj Hospital with dementia in December last year.

“He had very little control over his actions, and things became really difficult for him,” she recalls. “At its base, dementia is forgetting — things, people, your own stories are rendered unrecognisable to you.”

The doctors had all but given up hope, and Swastika’s parents even signed a set of definitive papers, declaring that they were forgoing ICU care to “lower the degree of his suffering,” the linguistics student studying in Japan tells ThePrint.

“He was in a lot of pain, he was being fed through a nose tube, and doctors were finding it impossible to find veins in his body to inject medicines,” she says. “However still, we tried to keep his spirits up, and we’d often ask, ‘Dadu, you’ll come back home very jaldi (quick), and when you do, what would you like to do first?’”

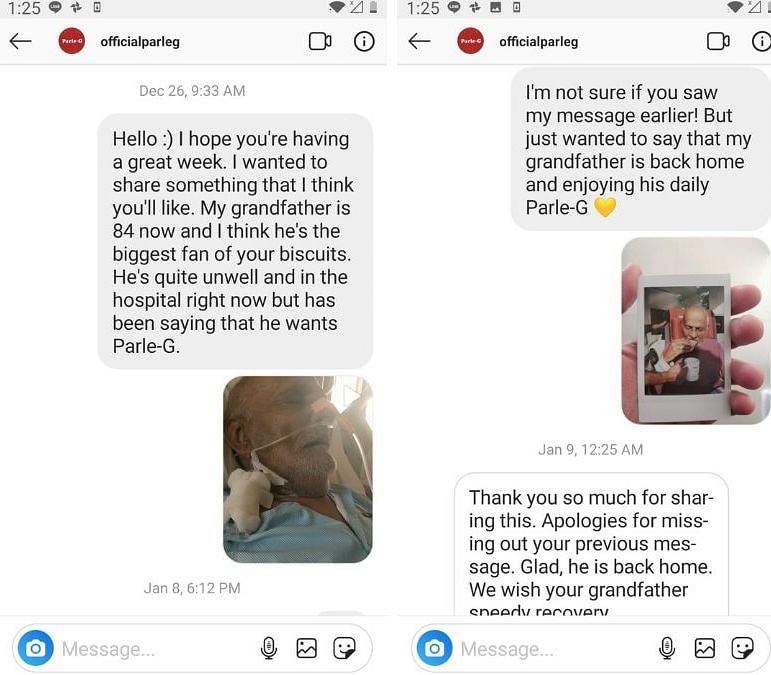

“‘Eat Parle-G biscuits and drink chai’, he said,” Swastika says through a smile. She shot a small video of the interaction on her phone and sent it across to Parle on their Instagram page.

By January, her grandfather was showing rapid signs of recovery. “It really was like a miracle,” she says. “We had called relatives from everywhere, because we had to prepare ourselves, and suddenly we were told that we can take him back home.”

Also read: Police rescues 26 child labourers from Parle-G biscuits factory in Chhattisgarh

“It was a delight to see him being able to drink his tea and eat his Parle-G biscuits — he eats one whole packet a day, has been for decades now. I sent a photo to Parle to thank them again, and this time, they responded by sending him a large 2.3-kg crate of Parle-G biscuits, a red Parle branded cup for his tea, and a personalised letter.”

“For us, something like this lends tangibility to a love that you’ve had for something for so long — I once wrote in a poem of mine that ‘We have Parle-G in our blood,’ and when I heard the news that its struggling, that 10,000 people might lose their jobs, I screamed. It just didn’t seem real to me,” she says.

Today, despite its pride of place in the cultural consciousness of India, Parle Products — the parent company that manufactures the popular Parle-G biscuits — is in trouble.

This week the company publicly announced that they were considering laying off up to 10,000 employees across various factories in the wake of consistently falling demand for Parle-G biscuits in the last two quarters.

In a series of interviews to the press, senior category head at Parle Products Mayank Shah cites “the tax (GST) hike and economic slowdown” as the primary reasons behind a drop in sales.

Further, while Parle’s Platina range (premium products) that includes Milano, Hide & Seek and Nutricrunch “have not been impacted by the economic slowdown” and “are still going strong,” Shah told India Today Thursday, “But our (lower-priced) product has been hit.”

“The volumes of Parle-G have declined by 7-8 per cent,” Shah said.

You could smell it before you saw it

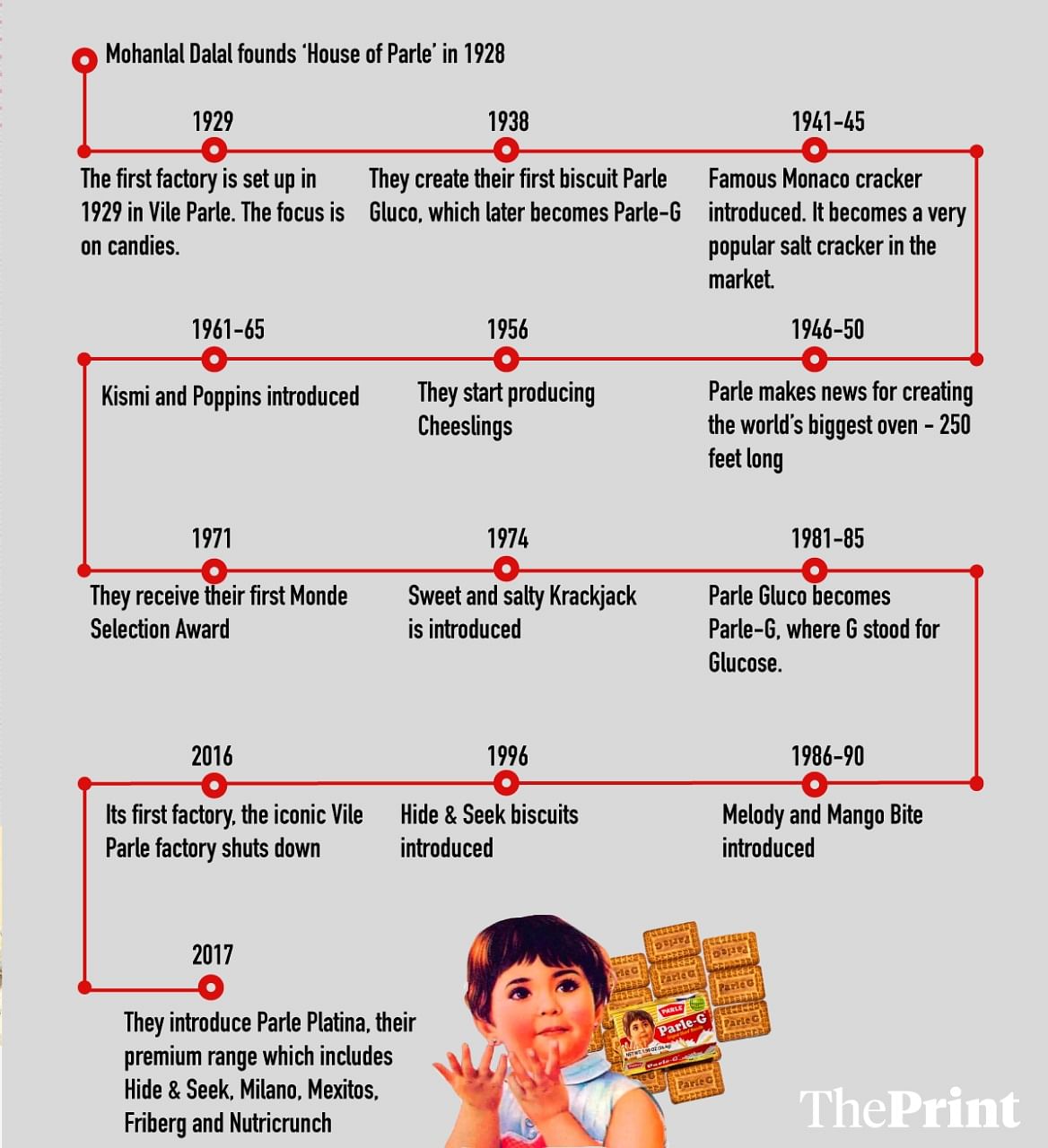

Cracks first started to appear when Parle’s iconic factory in Vile Parle, Mumbai, was shut down in 2016 due to a massive slump in production. It was the 90-year-old company’s first factory, set up in 1929 by founder Mohanlal Chauhan with just 12 employees.

The factory was not only integral to Parle’s history as a company, but was also a source of pride for the suburb from which it derived its name — Vile Parle.

After nearly 87 years of existence, the factory had become a historic landmark and the sweet fragrances that wafted from its kitchens were known to all those who passed Vile Parle in Mumbai’s local train.

Bharat Gothoskar, 44, left 17 years of work experience in sales and marketing for companies like Godrej, Pidilite and Mahindra behind him to pursue what he calls “a quest to rediscover and popularise Mumbai’s heritage.”

He now runs Khaki Tours out of the Wadala neighbourhood, but for the first 30 years of his life, he was a proud resident of Vile Parle, he tells ThePrint.

“Right opposite the first Parle factory in Vile Parle, there was a Gold-Spot factory on the highway — what is today Bisleri,” Gothoskar recalls, “and both became an integral part of Bombay’s historical sensory archive”.

“An actual, large Gold-Spot bottle sat atop that factory across the road, and you’d always look out for it when you crossed. And with Parle biscuits, you could make out what they were baking each day — Monaco, Parle-G or Krackjack — by the smell, and even the trains carrying the biscuits would leave behind a trailing scent of trail of glucose every morning,” he reminisces.

The desi product with a global presence

Apart from being a national favourite, Parle Products has stretched its arms in world markets that include the US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Middle East, and has manufacturing units in seven countries, besides India. But the company, which was established before Independence and inspired by the Swadeshi movement, had very humble beginnings.

Mohanlal Chauhan, the founding father of the legendary brand, dreamt of becoming a tailor and even opened a tailoring shop in Mumbai’s Gamdevi when he was 18, which soon evolved into a successful textile business.

Eventually, his sons joined the business and they took the decision to move out of tailoring and explore confectionary. His son Narottam set off to Germany to learn advanced modern confectionery techniques and returned with enough machinery for them to set up their first factory.

Unable to even afford engineers at the time, Mohanlal’s other son Jayantilal and his grandson Ramesh set up the plant themselves.

Like many family-run companies, the Chauhans could have chosen their family name to anoint the business legacy they were hoping to create, but instead, they chose their neighbourhood of Vile Parle.

Over time, the factory became an important presence in the neighbourhood and in the city of Mumbai. Often opening its doors to school children, Parle Products instituted factory visits as school field trips.

Mihir Joshi, a lawyer and Vile Parle resident, recalls, “Having always smelled the aroma of the biscuits but never having actually visited the factory, it was very exciting to visit for the first time. Right from the processing of raw materials, manufacturing, quality control, assembly and dispatch, we were taken through the entire process from scratch.Of course, the best part was the tasting session that was reserved for the end, when freshly baked biscuits and confectionery were handed out to us.”

Parle’s presence in the region was so ubiquitous that it soon became the stuff of legend.

“The myth goes, and every Parlekar will tell you, that a local Marathi-speaking Christian named Jack was employed at the Parle factory and accidentally mixed the dough for both Parle-G and Monaco,” Gothoskar tells ThePrint.

“They were planning to throw away the baked mixture, but then they tasted it and realised the flavour was quite good. That’s how Krackjack was born — named after the guy who messed up.”

When the factory closed, it was “an end of an era,” says Joshi, for whose family the factory meant more than just teatime snacks.

“For my parents, it symbolised a simpler time of the past, that could be held as a constant amidst the rapidly changing urban cityscape,” Joshi says.

When biscuits worth Rs 5 is too much, its troubling

When the country was reeling from the shock of demonetisation in 2016, Parle Products took a hit too, and the worst hit was its flagship biscuit, Parle-G.

As the note ban resulted in a loss of about Rs 1.2 trillion from the Indian consumer goods market, the company’s sales nosedived and consumer demand shrunk. And any hope of recovery was quashed when the government introduced GST in 2017, increasing the tax on the below-Rs 100 per kg biscuit category from 12 to 18 per cent.

In response, Parle had to raise prices by 5 per cent, which further reduced sales. Parle-G biscuits, which have stayed within the same price range of Rs 4-5 for its smallest packet since 1929, is now finding it difficult to push back against a levelling tax.

In an economic environment that is witnessing the loss of 2.30 lakh jobs in the automobile industry, a fall of 33 per cent in cotton yarn exports between April-June this fiscal year, and a significant decline in growth across the FMCG sector, the company’s gradual decline isn’t unbelievable.

However, a fall in demand for biscuit packets worth Rs 5 indicates something far more troubling about this economic downturn than a decrease in car sales does.

“… decline in car sales or slowing GDP growth…do not necessarily suggest a squeeze on the poorest segments of society,” Hindustan Times’s Roshan Kishore writes, “as the burden of a slowdown in economic activity can also impact the relatively well-off disproportionately.”

With an extremely low price point, Parle-G is a poor man’s biscuit, with 50 per cent of its sales coming from rural India.

As Mirror Now Editor Faye D’Souza pointed out in 2017, taxing glucose biscuits like Parle-G was a direct attack on poor mothers across the country who use them as a substitute for baby food like Cerelac. For context, the average daily rural wage as of June 2019 was a mere Rs 328.

The impact of an economic slowdown on Parle’s business will be significant — the company employs approximately 1,00,000 people across 10 company-owned facilities and 125 contract manufacturing units.

Recording an annual revenue of above $1.4 billion, the FMCG umbrella organisation has witnessed a gradual decline in growth for a few years now. In the financial year of 2017-18, Parle Products reported a 7 per cent revenue growth at Rs 8,487 crore, a slight bump from the Rs 7,922 crore the previous year.

However, as Business Line reports, “The growth was lower than in 2016-17, when the company recorded a 10 per cent growth in revenues over the previous year, according to data sourced from business intelligence platform Tofler.”

Still, the company doesn’t expect “free handouts,” Shah insists.

All it wants is for the government to rethink its blanket taxation policies that have crippled the home-grown biscuit company, which has been such an integral part of India’s cultural, economic and emotional heritage.

Also read: Sambit Patra’s ‘ice cream’ joke on Chidambaram, Mamata’s 90 books & Derek’s Parle-G crisis

Before GST era there was excise duty of 6% and vat of 12.5%(vat was levied on 6% ED also) so effectively total duty used to be 19.25%. Now it is 18%. It is lower. Why such a hue & cry…..