New Delhi: Even as the debate over freedom of expression and speech has been reignited over the last few days, with questions being raised about applicability of sedition laws especially in case of media and journalists, the irony of the situation can’t be lost.

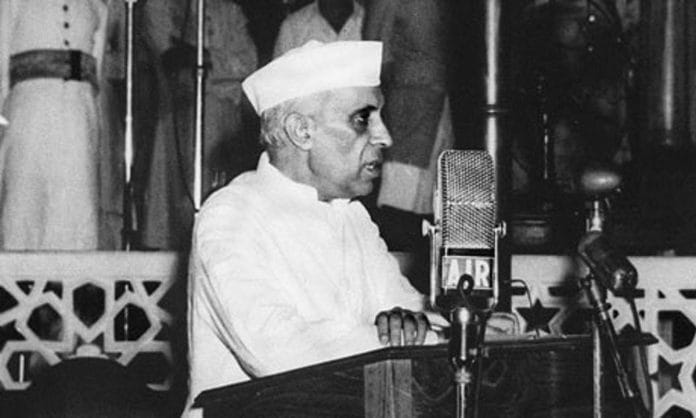

Seven decades ago, the first amendment to the Constitution of India was brought in by the then Jawaharlal Nehru government. This amendment, in addition to bringing sweeping changes in laws related to socio-economic issues, also drastically curbed the freedom of speech.

It was an outcome of the Nehru government’s intent to clamp down on voices critical of the government. Incidentally, one of the immediate triggers for restricting freedom of expression by Nehru was primarily the battle between him and Organiser, an English weekly backed by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh(RSS).

Organiser Vs Nehru

The Organiser was quite critical of the Nehru government in wake of the partition of India in 1947 and widespread communal violence against Hindus in Dhaka and several other parts of Pakistan.

In February 1950, the weekly published several reports critical of the Nehru government. These reports criticised the then Prime Minister’s policies and brought to the fore the plight of thousands of Hindu refugees, who were forced to migrate from East Pakistan to West Bengal after they were targeted in widespread communal violence.

The weekly demanded that the Muslim evacuee property should be distributed to Hindu refugees as they were forced to exchange blood for bread at blood banks.

As Nehru was facing heavy criticism for proposing confidence-building measures with Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, when Hindus were being targeted, the weekly published cartoons of Nehru and Liaquat and in a piece titled ‘Villains vs Fools’, it wrote, “the villainy of Pakistan is matched only by our idiocy”.

An infuriated Nehru decided to clamp down on the Organiser. On 2 March1950, the Central Press Advisory, a regulatory body under the Nehru government, met to discuss what had been published by the weekly. On the same day itself, an order to gag the weekly was issued by the Chief Commissioner of Delhi.

It was a ‘pre-censorship order’ and was issued under the notorious East Punjab Public Safety Act. This order made it mandatory for the editor and the publisher to submit to the government for approval, all content related to communal issues or Pakistan. It also included cartoons.

K.R. Malkani, the then editor of Organiser, was not to be cowed down. Malkani, who later became a Bhartiya Jana Sangh and BJP stalwart, hit back at this gagging order with a bold editorial on 13 March.

“If the administration earnestly wants ugly facts not to appear in the press, the only right and honest course for it is effectively to exert itself for the non-occurrence of such brutal facts,” the editorial read. “Suppression of facts is no solution to the Bengal tragedy. Surely the government does not hope to extinguish a volcano by squatting more tightly on its crater.”

Also read: RSS doesn’t run BJP by remote, it isn’t a school principal regulating BJP leaders as students

Battle in the court

On 10 April 1950, Organiser’s publisher and printer, Brij Bhushan, and Malkani went to the Supreme Court to get the pre-censorship order quashed.

Organiser was represented in court by N.C. Chatterjee, a former president of the Hindu Mahasabha and whose son Somnath Chatterjee later became a Left stalwart.

In this famous case, which is known in Constitutional history as Brij Bhushan vs The State of Delhi, Chatterjee argued that the pre-censorship order was an infringement on the freedom of speech. He also argued that the law under which this order has been issued doesn’t fall under any provisions in the Constitution of India. So the government’s pre-censorship order is illegal.

The case got widespread attention and ignited a nationwide debate. The Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court, Justice M.C. Chagla castigated the Nehru government in a public lecture at Pune on 1 May.

“The Constitution had not left it to the party in power in the legislature or the caprice of the executive to limit, control or impair any fundamental rights,” he said. “… The right to express opinion, however critical it might be of the government or society as constituted, was one of the most fundamental rights of the individual in a democratic form of government.”

P.R. Das, a prominent jurist, former judge of Patna High Court and brother of Congress stalwart C.R. Das, remarked, “The danger, which I apprehend is that the government may suppress all political parties that do not believe in the Congress government on the plea that the interests of the public order demand that these parties should be suppressed.”

Noted jurist and Governor of Bengal at that time, Kailash Nath Katju, warned, “We must take care that in the name of preservation of state and stopping of subversive activities, we may not stifle democracy itself.”

Also read: How Karl Marx’s grandson fought for Savarkar against British in International Court of Justice

The verdict

The Supreme Court gave its verdict in this case on 26 May 1950 in favour of Organiser, quashing the pre-censorship order.

The apex court order said that under Article 19 of the Constitution, restrictions could be imposed on freedom of expression only in certain cases that were given in clause 2 of the Article. Public order was not one of the grounds, so no restriction on the freedom of expression could be imposed on the grounds of ‘Public order’.

Following this defeat of his government in the court, Nehru then pushed for introducing more curbs on freedom of expression through the first amendment. Despite fierce resistance from within his party as well as in parliament and media on the issue of freedom of expression, Nehru moved the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951, on 10 May 1951 and it was enacted by Parliament on 18 June 1951.

(References:1.‘Sixteen Stormy Days’ by Tripurdaman Singh, Penguin Random House India’, Archives or ‘Organiser’, ‘Selected Works of Jawahar Lal Nehru’(New Delhi, Jawahar Lal Memorial Fund)

(The writer is a research director with Delhi-based think-tank Vichar Vinimay Kendra. He has authored two books on the RSS. Views expressed are personal.)

Also read: Why Bhagwat lecture wasn’t a ‘snub’ for Modi govt but had larger RSS message to fight Covid