Narmadapuram/Bhopal: Madhya Pradesh has transformed into an agricultural powerhouse in the past two decades, eclipsing Haryana and Punjab in wheat production and earning the title of the ‘soya state’. Agriculture now constitutes nearly half of the state’s economy. But warning signs are emerging that this boom could be waning, reminiscent of Punjab’s post-Green Revolution fate. This election season, farmers have several grievances.

Sunil Jat of Ratua village, 20 km from state capital Bhopal, has been a part of MP’s agri success story from the start. He grows soybean in the June-July kharif sowing season, and starts a wheat crop in the October-November rabi season. But though Sunil has been farming for 20 years, his life has not changed much.

Standing at the Bhopal mandi, where he had just sold his 2-acre soybean crop for Rs 3,800 per quintal, Sunil seemed more weary than pleased.

“Production has increased a lot compared to earlier. We grow more now than we used. But the cost of production has increased more than our income,” he said.

He is determined to educate his children so that they have other career options. “I don’t want them to deal with all the same troubles in farming,” he added.

But going by numbers alone, the farming sector presents a rosy picture in MP.

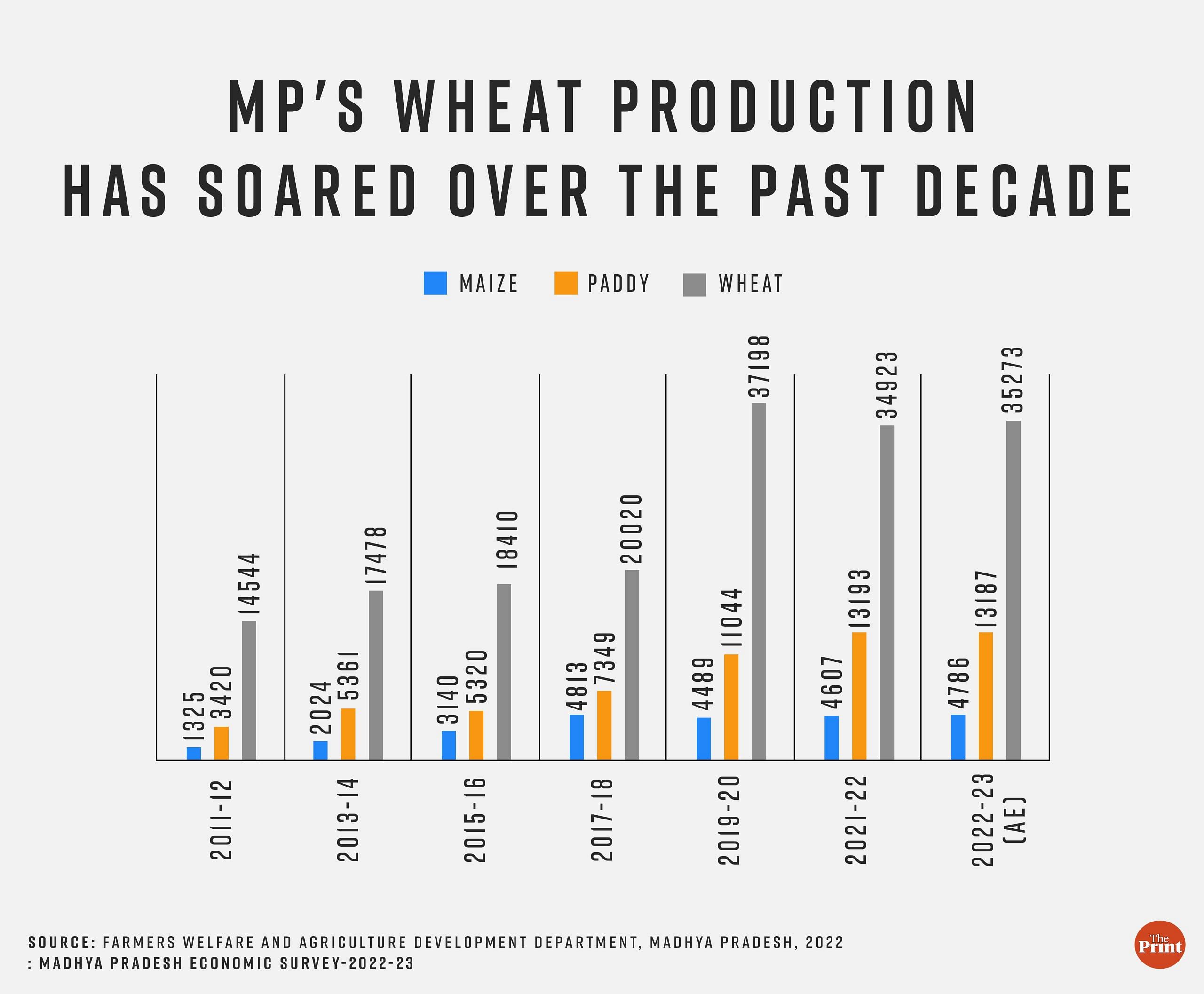

The state’s foodgrain production (rice, wheat, coarse cereals, and pulses) more than doubled from 149 lakh tonnes in 2011-12 to 349 lakh tonnes in 2021-22, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.12 percent.

Agriculture also plays the most important role in the state’s economy. In 2021-22, it made up 47 percent of MP’s economy and was the only sector to record positive growth (5.2 percent). Around 72 percent of the state’s population lives in rural areas, which indicates that nearly three out of four people are connected to farming in some way.

Agricultural experts attribute the boost in food crop production to four major factors: improved irrigation, loans given to farmers at zero percent interest, availability of high-quality seeds, good road networks across the state

“Due to better transportation, farmers are getting better prices in other places as compared to local markets. There was no irrigation facility in districts like Rewa, Shahdol, and Satna, but through the Bargi project, water was supplied there too,” said HD Verma, former dean of Sehore Agricultural College.

But while Madhya Pradesh’s economic growth story has been driven by agriculture, this hasn’t necessarily translated into an improved quality of life or per capita income for farmers. Excessive fertiliser use, soil degradation, and dwindling water resources have also soured the success saga.

Also Read: High on growth, low on development — what ails the economy of Madhya Pradesh

‘MP has pushed itself towards an agri economy’

The agricultural growth rate of MP was 3 percent in 2002-03, soaring to 18.89 percent in 2020-21, according to the state agriculture department. This remarkable growth well outpaces that of neighbouring states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

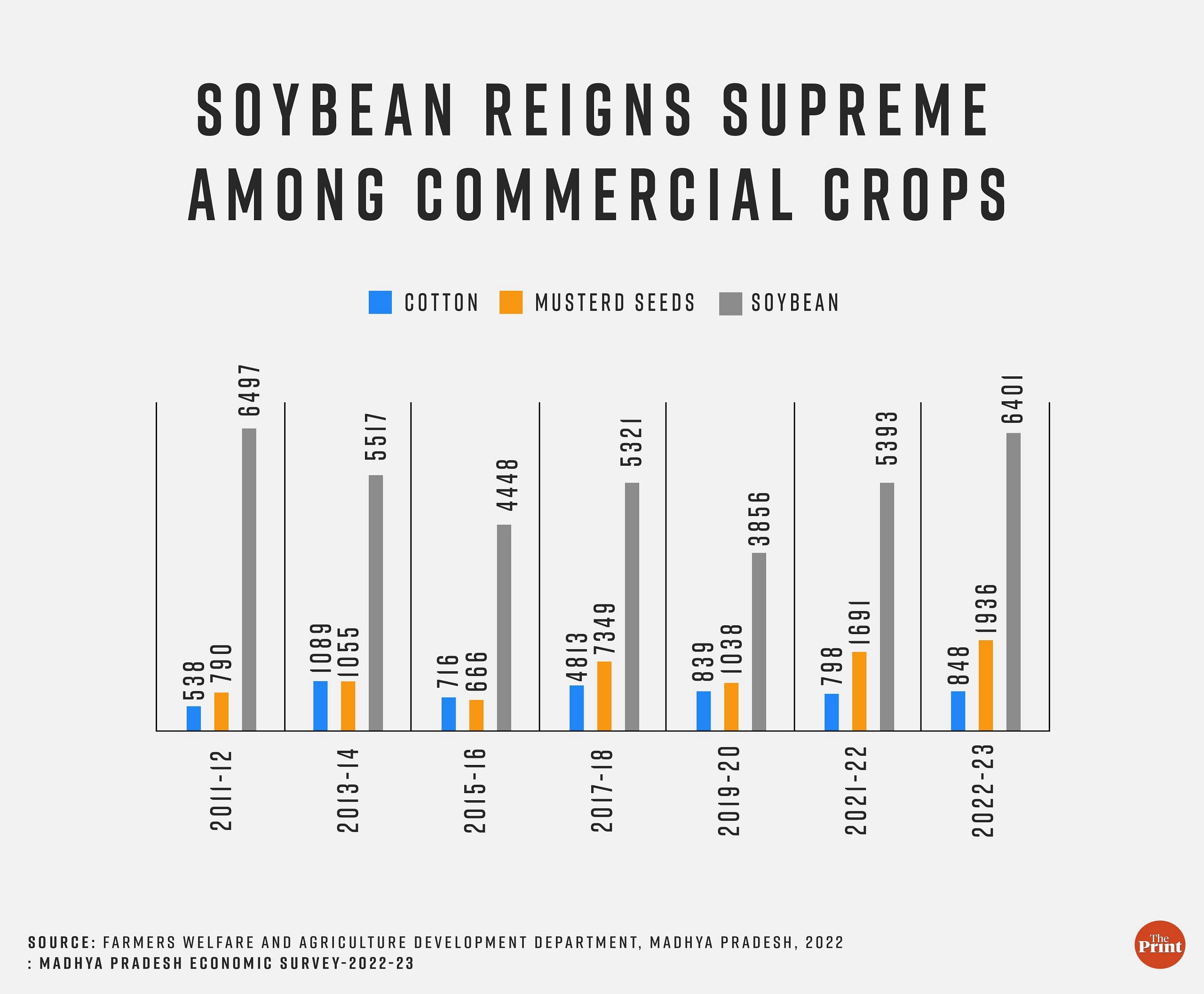

Madhya Pradesh is India’s largest producer of soybean, accounting for over half of the country’s output. It’s also the second-largest producer of wheat, after Uttar Pradesh.

While soybean production has had some ups and downs in the last decade, it has ramped up again in the last couple of years, going from 3,856 thousand MT in 2019-20 to 6,401 thousand MT in 2022-23.

Wheat production in MP increased from 174.8 lakh metric tonnes (MT) in 2013-14 to 349.23 lakh MT in 2021-22.

Earlier this year, Madhya Pradesh clinched the government of India’s prestigious Krishi Karman Award for foodgrain production for the seventh time in a row.

Swadesh Srivastava, a senior official in the Bhopal Agriculture Department, attributed the agricultural development of Madhya Pradesh to long-running government schemes.

“The government places a strong emphasis on input supply,” he said. “Every village was covered through Kisan Rath Yatras, where farmers’ problems were heard. Krishi Melas (agricultural fairs) have also been organised regularly,” he said.

Srivastava said that more farmers were drawn to wheat cultivation due to the Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana, an MP government scheme, launched in 2017, that compensated farmers for the difference between the MSP and the selling price of their crops.

“Wheat is a crop which is less affected by weather and losses are less. At present the average wheat production in the state is 38 quintals per hectare,” said Srivastava. Key wheat-producing districts include Narsinghpur, Hoshangabad, Sehore, Raisen, Bhopal, Vidisha, Sagar, Damoh, Ujjain, Indore, Khargone, and Satna.

Several other schemes have also encouraged farming in the state.

As of December 2022, 74.11 lakh farmers in MP have been issued Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs), of which 39.63 lakh were issued by cooperative banks alone, according to the agriculture department.

To protect farmers from the clutches of moneylenders, the government is also providing loans up to Rs 3 lakh at zero percent interest. The MP government also provides Rs 6,000 annually to farmers under the Chief Minister Kisan Kalyan Yojana.

In 2022-23, MP allocated 6.4 percent of its total expenditure to agriculture, exceeding the average allocation for agriculture by states, which stands at 5.8 percent.

“As the budget documents show, Madhya Pradesh has pushed itself towards an agri economy,” said Biswajit Patra, assistant professor in the Department of Economic Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Bhopal.

“Madhya Pradesh’s irrigation schemes and agri credit schemes are behind this agricultural growth rate which benefited the people,” he added, noting that the sector employs many people in the state.

The growth of MP agriculture production is also reflected from the sale of tractors in the past one decade,” said Patra. While more recent data was not available, tractor sales in the state witnessed a nearly four-fold increase from 24,306 units annually in 2008-09 to over 87,831 units in 2013-14, according to an Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) analysis.

Patra, however, acknowledged that the state’s economic growth was “not always reflected in the income” of farmers.

‘Farmers are just an election issue’

Half of Madhya Pradesh’s total land area is under cultivation and the state is home to over 98.44 lakh farmers. Of these, about 76 percent are small and marginal farmers.

Farmers and experts alike said that the ground realities behind the growth story were sobering— rising costs for farming inputs, stagnating incomes, and a lack of market security. A shortage of storage facilities, leading to crops spoiling, is also a widespread complaint.

Rajesh Kumar Gautam, professor and anthropologist at the Hari Singh Gaur University in Sagar, said that a change in crop pattern had driven up agricultural production in MP, but farmers were still struggling.

“Land holdings in Madhya Pradesh are already very small and are getting even smaller due to family splits, which directly affects individual income,” he said.

Input costs for labour, equipment, and other agri essentials have also soared. “Income will increase only if the costs in agriculture reduce,” said Ashok Patra, former director of the Indian Institute of Soil Sciences.

Farmer leader Rahul Raj concurred. “The cost of cultivation is not practical. The rural economy depends on farmers, but farmers have become only an election issue that no one can solve,” he said.

In the lead-up to the state assembly elections, the BJP and Congress parties are vying for the support of farmers.

The Madhya Pradesh Congress has put up posters that read “18 saal kisan badhaal. Bas bahut hua. Vote nahi, maafi mango Shivraj (18 years of farmer neglect. Enough is enough. Shivraj, don’t ask for votes, ask for forgiveness).”

In its manifesto, the Congress has also promised to waive farm loans, provide free 5 HP electricity for irrigation, purchase cow dung at Rs 2 per kg, end old cases against farmers, and waive their electricity bills. Congress leader Kamal Nath has claimed that during his party’s 15 months in power, loans of 27 lakh farmers were waived off.

The BJP, meanwhile, has contended that the Chouhan government has already provided subsidies to farmers using five horsepower pumps, waived electricity dues during the pandemic, taken back cases against farmers, and begun providing 12 hours of electricity per day.

But this election season, farmers have numerous grievances.

“The food grain production that has increased in Madhya Pradesh is mostly in the Malwa region and Narmada valley. And the real challenge before the farmers is the procurement of crops,” farmer Raj said.

According to him, farmers predominantly cultivate crops with high cash potential, such as wheat, paddy, and soybean, while those engaged in the cultivation of alternative crops often face financial challenges.

Raj pointed to the 2017 farmers’ agitation in Mandsaur, when six protesters were shot dead by police, leading to a huge political controversy ahead of the 2018 election. The farmers had been protesting for an increase in the minimum support price.

At the time, the MP government had encouraged crop diversification, leading many farmers to switch to onion cultivation. However, due to a surplus in production, farmers claimed they did not receive adequate prices

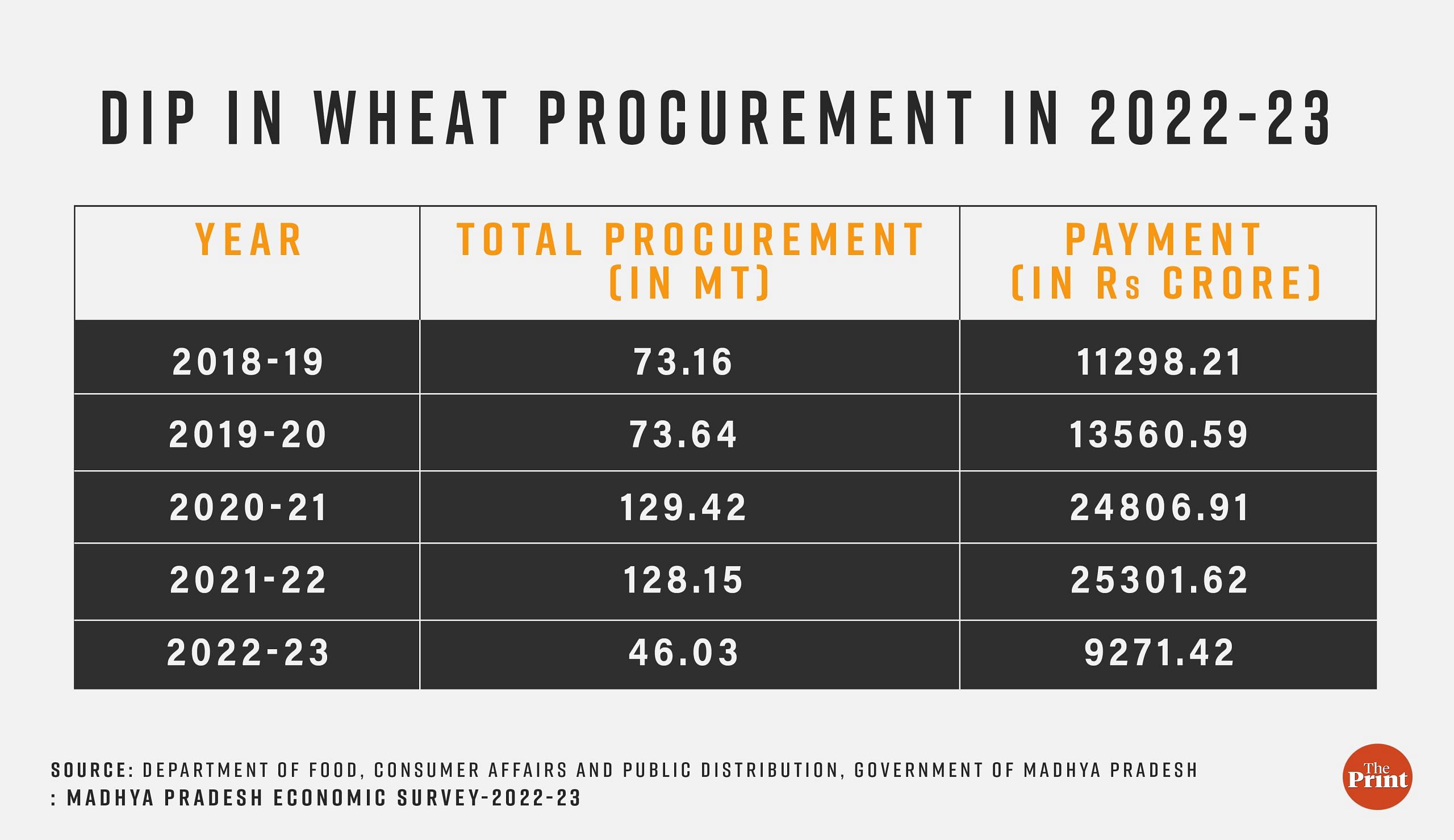

Wheat procurement, notably, went off balance too in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict due to a spike in prices in the open market.

According to the 2022-23 Economic Survey of Madhya Pradesh, procurement of wheat dropped to 46.03 MT in 2022-23 from 128.15 in 2021-22.

Farmers also emphasise other systemic issues such as lack of development in the agri-processing sector, particularly in harnessing resources like soybeans for the oilseed industry and wheat for ethanol production.

Further, government mandis suffer from inadequate storage facilities, resulting in crop damage during the rainy season. For instance, in September this year, hundreds of quintals of garlic were ruined due to exposure to rain in Mandsaur Mandi.

There is also a shortage of cold storage in the state and most of it is in the hands of private players. Out of the 250 cold storages in the state, only five are government-run.

“Small farmers do not have the option to keep the crop in cold storage. The cost of storing crops in private cold storage is very high. Only big farmers can do this,” said farmer Sunil Jat, quoted earlier.

Irrigation projects— a mixed blessing

The Narmada River is the lifeline of Madhya Pradesh, both for drinking water and agriculture.

Over the past two decades, Madhya Pradesh has undertaken numerous irrigation projects aimed at channelling the Narmada River’s waters to the fields to facilitate farming.

Data from the state irrigation department shows that in the last three years alone, 179 new irrigation projects have been initiated, leading to a substantial increase in irrigation capacity. In 2013, the state’s irrigation capacity stood at 7.5 lakh hectares, but by 2023, it had surged to 47 lakh hectares, with a target to further expand to 65 lakh hectares by 2025. There are currently 475 new irrigation projects in progress.

CM Chouhan has also prioritised irrigation projects in the runup to the assembly elections. Over the last few months, he has laid the foundation stones for dozens of irrigation projects, including in Harda, Narmadapuram, Khandwa, Alirajpur, and Khargone districts.

With water supply becoming more abundant, there have been significant changes to agriculture in the regions surrounding the Narmada River.

Dr Kashmir Singh Uppal, a former economics professor at Itarsi College, said that coarse grains and pigeon peas were widely grown in Narmadapuram and its surrounding areas until the 1970s and 1980s. However, in 1972, when the Tawa Dam was built, farmers began to grow wheat and rice instead.

Farmer Hemant Dubey, a resident of Zamani village of Narmadapuram (earlier Hoshangabad), said that paddy was now more popular than traditional crops. “Now people grow more paddy than even soybean,” he added.

Another new trend in the region, Dubey said, is the cultivation of moong as a third crop between the kharif and rabi seasons.

Moong cultivation in Narmadapuram district has grown from 62,000 hectares in 2014 to 293,000 hectares in 2023, with a corresponding boost in production from 1,150 kg per hectare to 1,600 kg per hectare, according to data shared by JR Hedau, head of the district agriculture department.

However, this bounty has come with some side effects, including increased pressure on the soil and the practice of stubble burning.

“As soon as the rabi wheat crop is harvested, farmers start setting fires to clear the fields so that the third crop can be planted. With the increase in moong cultivation, incidents of fire have also increased significantly,” said Prashant Chaudhary, a farmer from Itarsi in Narmadapuram.

In 2019, stubble burning in Narmadapuram affected many villages on a large scale, killing three people.

Amar Singhekalme, a farmer from Khatama village in Kesla block, Narmadapuram, said that farming used to be dependent on nature alone, but that has changed. “When water started reaching the fields, people switched crops. With the construction of tube wells and canals, new crops began to be grown in this area,” he said.

Uppal pointed out that agricultural production has undoubtedly increased due to better irrigation facilities, but at a cost.

“With the increase in irrigation, the use of chemicals in this area has also increased significantly. Now, chemicals are sold in every village, which is polluting the land,” he said.

The groundwater level is also declining in Narmadapuram district.

“Earlier, water was available at 70-80 feet, but now it has reached 180 feet. The lifespan of borewells is also short,” he said. “Crops like wheat and paddy require a lot of water. A lot of water is used to produce these crops. In a way, water is also a curse,” Uppal said.

But if some regions have a problem of plenty, others still largely rely on rainwater for irrigation.

“Farming is done on about 180 lakh hectares in Madhya Pradesh, but irrigation is only done on 45 lakh hectares,” said Kedar Sirohi, a former member of the MP Agriculture Advisory Committee. “Water still only reaches one-fourth of the fields. Production in the state’s tribal areas is still very low because they are still reliant on rainwater.”

Also Read: Hungry India, a nawabi US President, ‘Mexican blood’ — The real story of Green Revolution

On the Punjab track?

With its push for high-yield crop varieties, modern farming techniques, and increased fertiliser use, the Green Revolution of the 1960s-70s turned Punjab into a top producer of food grains, the proverbial ‘bread basket of India’.

However, this came at a cost, both ecologically and economically. The excessive use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides caused soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and water contamination. Punjab’s economy was also overly reliant on agriculture, leading to unemployment, urban migration, and stunted industrial growth. In hindsight, the revolution is often called a failure.

Some experts have raised concerns that MP could be following a similar path.

In Narmadapuram, the soil is fertile and there is no shortage of water, but wheat production has stagnated over the last few years, hovering between 48-50 quintals per hectare, according to a Mongabay report.

Uppal said that the “indiscriminate” use of fertilisers has contributed to this problem.

“The lands of Madhya Pradesh have now reached such a state that without medicines they do not produce crops at all. The quality of the soil continues to deteriorate,” he added.

The MP Economic Survey shows that fertiliser use in MP has doubled in the last five years. According to CEIC data, 96.4 kg fertiliser was used per hectare in Madhya Pradesh in 2021, up from 93.060 kg per hectare in 2020.

Uppal told ThePrint that a similar situation arose in Punjab after the Green Revolution and that MP seems to be heading in the same direction.

“MP has adopted the agri methods of Punjab but has not learned from the failures there. At present, there is an increase in food grain production, but the state may face a crisis in the coming few decades,” said Uppal.

Professor Verma echoed these concerns. “Looking at the current situation, it can be said that Narmadapuram and Harda can become Punjab in the future,” he said.

However, SN Mishra, vice-chairman of Narmada Valley Development Corporation and former irrigation secretary of Madhya Pradesh, said that the two states could not be compared.

“Madhya Pradesh has adopted a long-term strategy, unlike Punjab. Work on pipe-based irrigation projects is also going on in the state, while organic farming is also growing rapidly,” he said.

Soil expert Ashok Patra, while acknowledging the harmful effects of fertiliser overuse, said that MP was unlikely to emulate Punjab’s mistakes.

“Farmers are much more aware now compared to that time and the government is also paying attention to the environment,” he said.

A push for organic farming

Amit Dubey, a resident of Dewas, left his corporate job and started organic farming in Madhya Pradesh about five years ago, using strictly sustainable practices.

“There are a large number of people doing organic farming in Madhya Pradesh, he said. “There is a lot of scope in this field, which can greatly benefit the entire economy.”

While MP continues to increase food grain production using fertilisers, it is also emphasising organic farming.

The state has the largest area under organic farming in the country, at 16.37 lakh hectares, according to the agriculture department.

Last year, Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan announced that “natural farming” would start in 5,200 villages of the state as a measure to restore soil health and productivity, which had been damaged due to the overuse of fertilisers.

The government also introduced the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) in 2015-16, offering comprehensive support for organic farming. It includes financial aid of Rs. 50,000 per hectare over three years, with 62 percent disbursed directly through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) system for inputs like bio-fertilisers, bio-pesticides, and organic manure.

Professor HD Verma contended that the widespread adoption of organic farming could shield Madhya Pradesh from long-term problems

“It may lead to losses (for farmers) in the initial years because there will be a reduction in production, but the government can balance this out by giving compensation.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Ashwagandha is the new gold rush for Indian farmers. King of Ayurveda is on global wishlist