Ludhiana/Karnal: It’s a sunny February morning in Katlaheri in Haryana’s Karnal. As 36-year-old Sita Devi steps out of her home to power on her electric autorickshaw, curious neighbours hurry to catch a glimpse of what she is about to do.

“Ever since I returned from Manesar in Haryana, villagers here wonder what I have learnt and what it is that I do,” she tells ThePrint smilingly as she boards her auto.

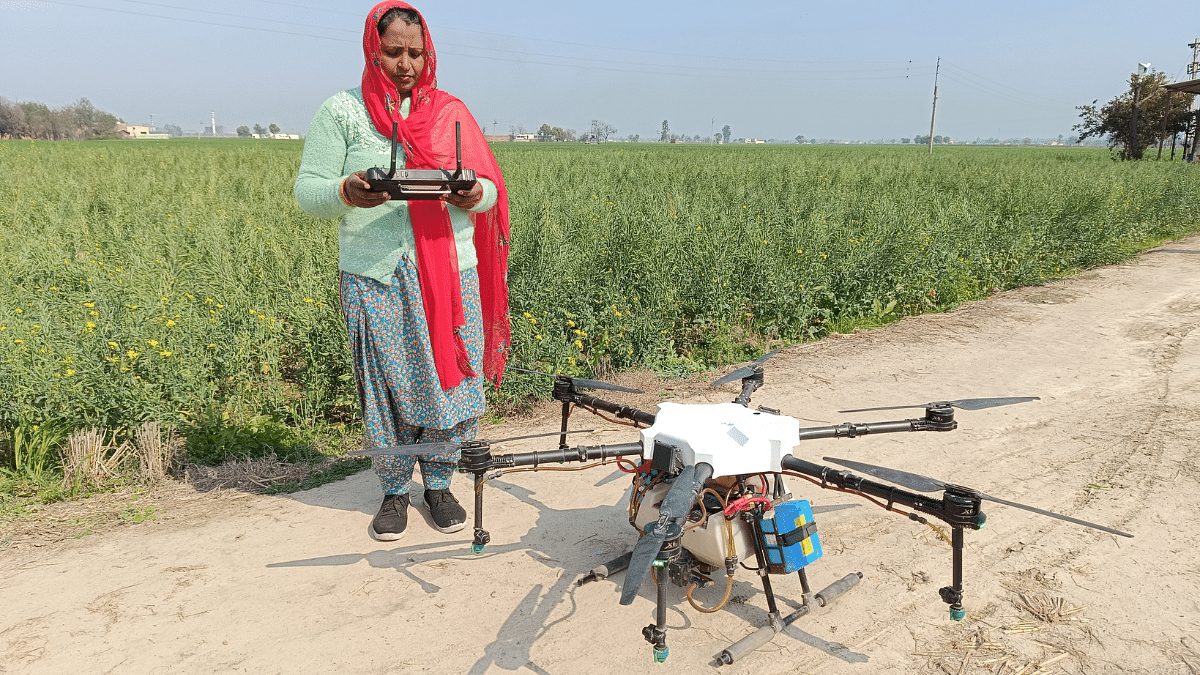

Sita is on her way to some nearby fields to work as ‘NaMo Drone Didi’ — a name given to women drone pilots who have been trained under the Narendra Modi government’s ‘NaMo Drone Didi Initiative’.

The scheme, which Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced from the ramparts of the Red Fort during Independence Day last year and launched last November, is aimed at training and equipping 15,000 women-led Self-Help Groups (SHGs) with agricultural drones. The idea is to offer farmers assistance in agricultural operations, such as crop monitoring, spraying fertilizers, and sowing seeds, thus helping rural women achieve self-sufficiency while simultaneously making the sector less labour-intensive.

For this, women like Sita undertake a certified training course at designated centres.

According to Digitalsky, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation’s (DGCA) database for all drone-related activities, there are 81 such centres including Drone Destination, a drone training institute at Manesar, where Sita trained.

Once they finish the course, these women get the Remote Pilot Certificate (RPC) — the certification required to fly drones — from the DGCA and can take up assignments as ‘Drone Didis’.

This morning, for example, Sita, who got RPC in December, is on her way to spray nano-urea across acres of fields in her village. “The girls in the village are very proud of me and happy to see my drone,” she tells ThePrint.

But three months since its launch, the scheme has already found sceptics. Agriculture policy analyst Devinder Sharma believes agriculture has, over the years, become the dominion of a few companies and it’s their interests that this scheme aims to further. The idea, he adds, is not to empower women but to help boost the GDP.

Significantly, the Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative (IFFCO) — a farmer-owned fertilizer collective and India’s largest fertilizer company — has been part of the NaMo Drone Didi Scheme since its inception. IFCCO produces two major fertilizers — nano urea and nano DAP — both of which the Modi government has been promoting.

“The application of drones is not to help Drone Didis in improving their finances, because there are many other ways to do that. It’s only a scheme to promote the use of drones. As more drones sold the more the GDP grows, let’s not forget this,” he says.

However, a scientist at Hyderbad’s ICAR-Indian Institute of Maize Research, an autonomous research organisation under the Department of Agricultural Research and Education, dismisses these allegations saying it’s too soon to pass any judgement on the scheme.

“The scheme has just been finalised and work under it has yet to be done on it,” he says.

ThePrint reached senior officials in the agriculture ministry for comment via calls and email but had not received a response by the time of publication. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

Also Read: BJP Mahila Morcha reaching out to ‘silent voters’ with Modi’s Lakhpati Didi, Drone Didi initiatives

How ‘Drone Didi’ scheme works

During his Independence Day speech on 15 August last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about leveraging the potential of science and technology in areas such as agriculture. He also announced that 15,000 Women’s Self-Help Groups would be given a loan and offered training for operating and repairing drones between 2024-25 and 2025-2026.

Under the ‘NaMo Drone Didi Initiative’, district authorities such as local collectors help handpick the women who could be recommended for training. The National Rural Livelihood Mission, under which these women self groups come, also recommends candidates.

Anurag Shukla, general manager (training) at the Manesar centre, says training costs approximately Rs 65,000 and currently lasts about five days. Then there’s a four-day ground training that comes at an additional cost of Rs 16,000.

According to officials, the initial training is sponsored by companies while the trainees themselves pay for the subsequent one. While IFFCO was the first to get on board — not only training for the first 300 women but also paying for drones (estimated to cost between Rs 8 and 13 lakh) and miscellaneous things such as its batteries — several other companies have since become part of the scheme.

These include not only fertilizer companies like Chambal Fertilisers and Chemical Limited, Indian Phosphate Limited, and Hindustan Urvarak & Rasayan Limited (HURL) but even agri-tech companies such as Iotech World, a collaboration (titled Project STREE) between HDFC Bank Parivartan and financial consultancy firm Grant Thornton Bharat.

Every woman who undergoes training gets a certificate, and eventually, a drone. Since its official launch, the central government bears 80 percent cost of these drones while the trainees pay the rest, officials said. In the interim budget announced this month, the Modi government earmarked Rs 500 crore for the ‘NaMo Drone Didi’ initiative.

Drone Didis — against all odds

It was in January that 45-year-old Laxmi Ghaghare from Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara got a call for training, she says while at the Drone Destination in Manesar’s Pataudi Road.

Ghagare was one of 20 people undergoing when ThePrint visited the centre earlier this month.

“Chambal Fertilizers, the company that’s sponsoring my training, told me I had two days to get Manesar for training. In my excitement and hurry to inform my husband, I burnt the sabzi I was cooking,” she laughs, her eyes still on the drone simulation on the computer in front of her.

She then narrates how other villagers mocked her when she was leaving. “They said: ‘Chali hai badi mastarni banne, kya karke ayegi, (set out to become a skilled master, what will she achieve),” she says, a steely determination creeping into her voice. “I have come here and will return after becoming a successful drone pilot.”

All drones that the women receive under the scheme are registered under the DGCA.

In March 2021, the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) introduced the Drone Rules, 2021, which allowed the use of drones in agricultural fields under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY). According to Digital Sky, there are currently 9,416 certified drone pilots and 18,667 drones registered in India. This includes 4,874 ‘small drones’ with a payload of up to 25 kg and 3,426 ‘medium’ drones with a payload of 25 to 150 kg.

All women undergoing training get a licence, or certification, under the medium category. A pilot under the initiative could potentially earn up to Rs 400 for each acre of land, officials said.

But for these aspiring ‘Drone Didis’, many of whom have never crossed the borders of their districts, the initiative offers more than a mere employment opportunity — it gives them a chance push to past their limitations and change their narratives.

“It challenges the stereotype that women are confined to the kitchen,” Lakshmi, a 36-year-old from Rajasthan’s Jhunjhunu district, tells ThePrint.

There are, of course, other advantages. For instance, Ritu, a 27-year-old from Karnal’s Balu village, talks about how her “status” changed in the village since she returned.

“When I returned (from Manesar) and recounted what I learnt to my friends, they didn’t understand much,” says Ritu, who is currently finishing her graduation. “But they told me ‘tu akeli padhi likhi hai hamare group me, tune kuch seekha hai, acha hi kiya hoga’ (you’re the only educated one in our group, so whatever you’ve learnt must be commendable.”

However, despite this, the training came at a cost for some.

At Lapran village in Punjab’s Ludhiana, Rupinder Kaur, 38, had to leave her four-month-old daughter with her mother in November, when she underwent training.

“I come from a farming background and so have already worked in fields. But with this, the Prime Minister has given us girls the opportunity to venture out and achieve something. Our lives may still be confined to these villages, but now we can proudly tell our children that their mother is a (drone) pilot,” says Rupinder, sitting in her house amid mustard fields while feeding her daughter.

Manpreet Singh, a manager at GT Bharat, admits to ThePrint that despite having licences, several pilots in Punjab are yet to receive their drones.

“Drones being handed over to them,” he adds.

Coursework & criticism

Currently, the course follows DGCA norms for drone training. This includes theoretical sessions, using computer simulations to fly drones, viva, and finally, a practical exam.

But the Union agriculture ministry has ordered a review of the curriculum for the drone initiative, Satyender Kumar Yadav, deputy director of Haryana’s Department of Horticulture, tells ThePrint.

Yadav, chief drone instructor at Karnal’s first government remote pilot training organisation — the Drone Imaging and Information Service of Haryana Limited (Driishya) — was part of the Agriculture Skill Council of India committee that designed the original coursework.

The Agriculture Skill Council of India (ASIC) is a not-for-profit organisation that comes under the Union Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship.

According to Yadav, the new coursework will include three additional days of training on the fundamentals of agriculture — including lessons on which plant requires which fertilizer.

“The course has been prepared but the final approval has yet to come from the ministry,” says Satyendra Arya, chief executive officer of the ASIC.

Agricultural policy analyst Devinder Sharma compares the use of drone technology to the way the third green revolution changed the agricultural scene across the world. But he also worries about its impact on jobs.

The Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields across the world, including in India.

“Today rural wages have been stuck for the last ten years. Making Drone Didi to help strengthen the rural economy cannot be the solution,” he tells ThePrint.

But even this lack of conviction does nothing to dampen the spirits of those this initiative is meant to benefit. At the Manesar training centre, 36-year-old Suman Rani beamingly shows a photo of her 8-year-old son, whom she left behind at Rishpur village in Haryana’s Panipat when she came to Manesar for training.

“Mere bete ne kaha hai, mummy pilot ban kar ana (my son insisted, you must return as a pilot),” she says proudly, holding up a photo of her son.

This is a sentiment with which Jaswinder Kaur Dhaliwal, who was one of the first women to undergo the drone training last year, agrees.

“Assi thaan leya si ki aittho jitt ke hi jaana, apa drone leke hi ghar jaana’ (we had decided that we would only return victorious and we will return home only with the drone),” says Dhaliwal, sitting on a jute cot with four other women at Rattian village in Punjab’s Moga.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Haryana’s first female drone pilot has admirers all the way from Japan, US