With a population that’s swelling by about 700,000 each year, India’s capital could be the world’s biggest megacity by 2028.

London: The effects of unbridled urbanization are inescapable in India’s capital city. Smog blankets landmarks like India Gate in winter, delaying flights at the airport due to poor visibility. Traffic jams are part of the daily routine and slums abut New Delhi’s luxury hotels and private mansions, testifying to a growing wealth divide and chronic housing shortage.

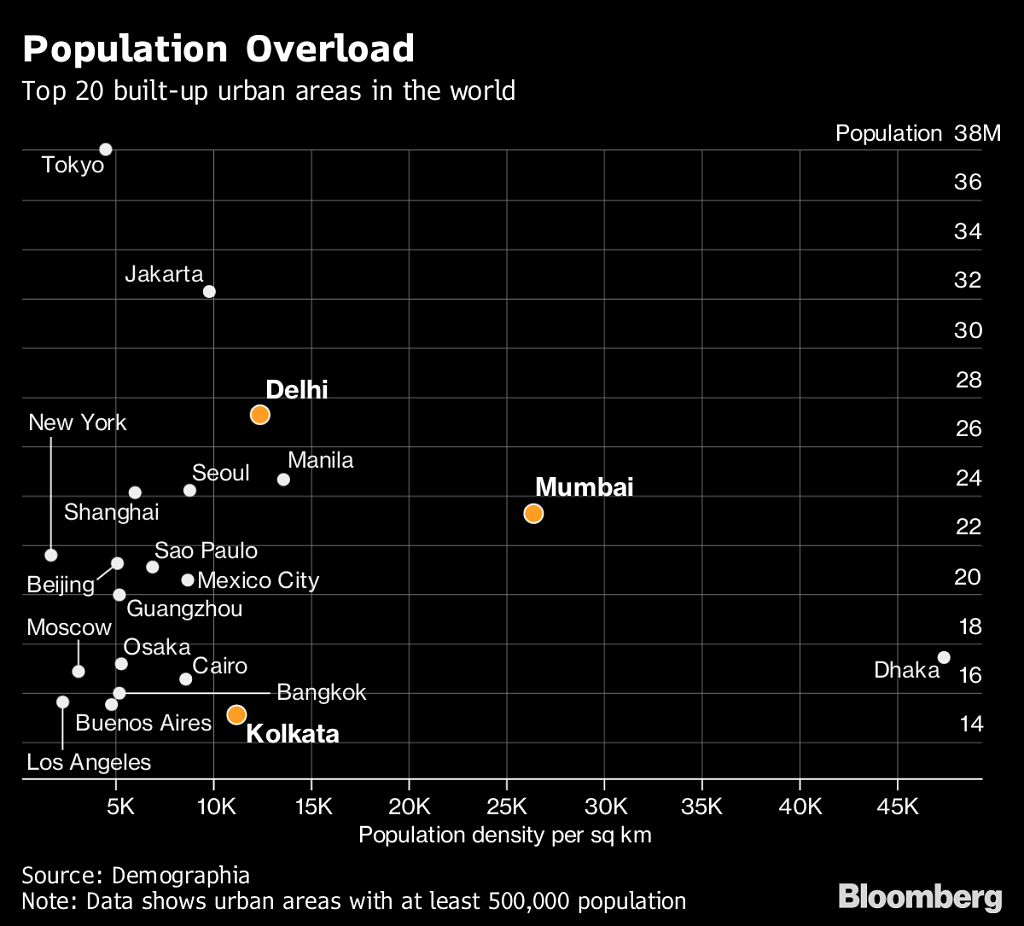

And every day, the problem gets bigger. More than 27 million people live in and around Delhi with about 700,000 more joining them each year, according to research firm Demographia. The United Nations forecasts that by 2028 the population could outstrip Tokyo’s to make Delhi the world’s biggest megacity.

India’s capital chronicles the extremes of a story that is playing out around the world as a flood of people in countries poor and rich move to the biggest cities that generate the lion’s share of economic activity. Already, more than half the planet’s population is urban and the proportion is expected to exceed two-thirds by the middle of the century.

The fallout of that shift hinges on whether governments can provide the necessary services and infrastructure to match that growth, an undertaking that some analysts estimate could cost as much as $78 trillion over the next decade.

The challenge isn’t lost on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which has set ambitious targets to provide “housing for all” by 2022, and is upgrading transport, sewage and drainage systems across India. Technology is being harnessed to develop “smart cities,” that better manage traffic, water, waste and other urban systems.

But the unabated growth of New Delhi makes it hard to keep up. Since 2005, the government’s two main housing programs for the poor have built about 43,000 new homes in Delhi. In the same time, the capital’s population has risen by as much as 10 million, according to data from Demographia, in large part due to the arrival of poor rural migrants.

“Between now and 2030, we need to build something like 700 to 900 million square meters of urban space every year, which means one Chicago every year,” Hardeep Singh Puri, India’s Minister for Housing and Urban Affairs, said in an interview in his office over gold-rimmed, porcelain cups of tea. “Can this be done? I don’t think that’s an appropriate question — you have no option but to do it. And you have to do it in a green and resilient manner.”

India has the world’s fastest-expanding major economy, which has helped lift millions out of poverty in the past decade. But inequality is growing. Many are above the official urban poverty line of 47 rupees (64 cents) a day but are not quite middle class and are vulnerable to shocks, according to Sumila Gulyani, program leader for infrastructure and sustainable development in India at the World Bank. What’s more, non-monetary measures of poverty, like access to healthcare and education, are sometimes worse for the poorest urban inhabitants compared to their rural counterparts.

“Housing hasn’t kept pace and environmental issues have lagged,” Gulyani said. “The inability to manage this massive influx, to keep pace with needs for infrastructure, services and housing, and sustain the environment, has reduced the kind of economic returns that you would expect to see from this massive urban population growth.”

Government efforts to remedy the housing problems have been beset by difficulties over land acquisition, relocation, infrastructure and environmental concerns. One of Delhi’s flagship smart city projects — the development of an enclave for civil servants in the East Kidwai Nagar district — shows some of the obstacles that can make urban regeneration a slow and painful process in India.

The project, begun in 2014, will replace 2,444 old low-rise homes with 4,608 apartments in modern 14-story towers, together with car parking and retail space. Scheduled to be completed by June, the 87-acre project is touted as a poster child for new government housing, with solar panels, on-site waste management and rainwater harvesting.

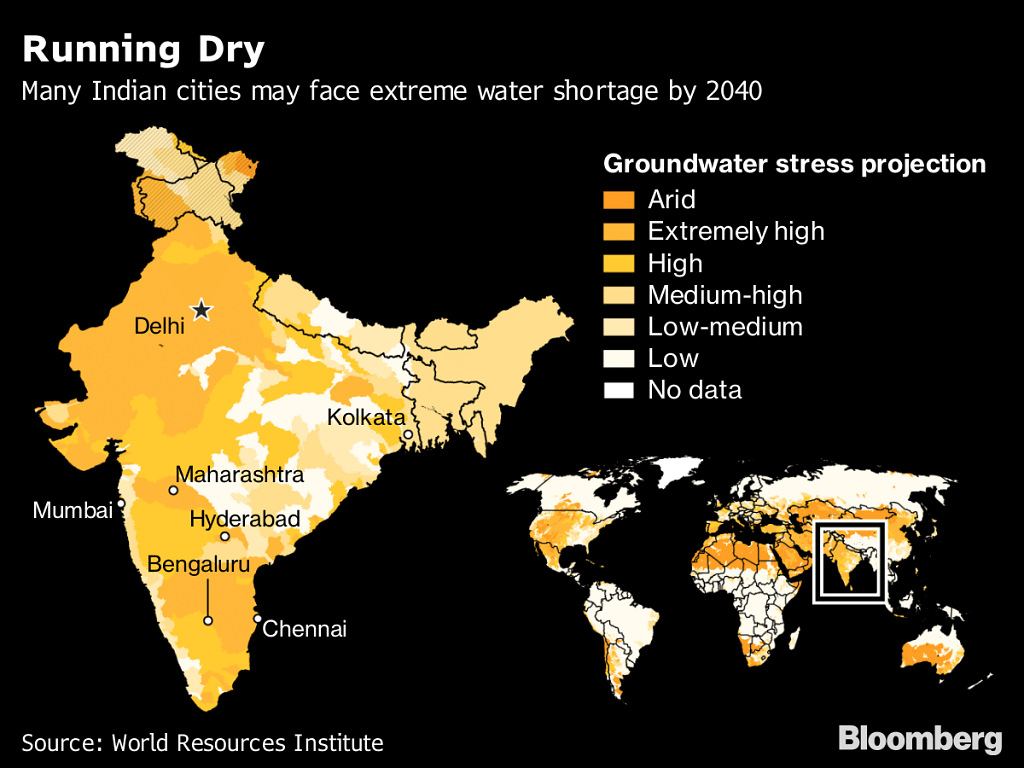

But the project has angered many locals, with lawsuits filed over traffic and environmental concerns, and compensation for existing residents. Almost 2,000 trees were cut down, and while some new ones are being planted, critics say a 10,000-space basement parking garage will restrict the replanting of large trees on the site and could threaten groundwater supplies.

At least 20 Indian cities, including New Delhi, are set to run out of groundwater as early as 2020 if measures aren’t taken, according to government think-tank NITI Aayog.

“These are acute problems in a city which these projects are actually aggravating more than mitigating,” said Kanchi Kohli, an environmental researcher at the Centre for Policy Research. “We need development in the city that helps address these problems.”

Delhi’s high court ruled in August that some of the commercial property on the site — which is being used to fund the development — can’t be handed over while questions remain over how water will be supplied and traffic managed.

Even when it’s complete, the new district will have added only 2,164 units after five years of construction. To keep up with the city’s growing population, hundreds of such developments are needed.

And that presents an even bigger difficulty. Over 200 families living in slums in East Kidwai Nagar were relocated 15 miles away to the Western edge of the city, to make way for the new gated community.

Urban planner and architect Ranjit Sabikhi says that type of geographical segregation of the poor can create serious social stresses in cities.

“It’s a very unhealthy concentration, and large numbers of our population are living in conditions with no schools, no health centers, no open spaces for children to play,” Sabikhi, who previously taught at Harvard, said in an interview in his studio in Delhi. Instead, “you could have a whole series of mixed housing, for both government as well as for low-income groups.”

A spokesman for India’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs said the slum dwellers from East Kidwai Nagar were moved to a “central” area “close to the airport.”

The separation of income classes is a global problem that has fueled social discontent in cities from Sao Paulo to Baltimore.

“This geography of haves and have-nots is creating the greatest political backlash — and the greatest political crisis of our time,” said American urbanist Richard Florida. “Having urbanization doesn’t mean that you’re going to lift all or even many boats. What tends to happen is you have a very lopsided, or spikey, or winner-takes-all globalization.”

In India, much of the migration to cities is “hidden,” with the urbanization rate probably closer to 55 percent, rather than the official estimate in the 2011 census of around 32 percent, according to Gulyani at the World Bank.

And the bigger the city, the more attractive it becomes for migrants. By 2030, the world is projected to have 43 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants, most of them in developing regions.

“A lot will depend on how cities are managed,” Gulyani said. “Right now we’re having a severe set of management issues.” Key to improving the efficiency of cities is to empower local authorities who are better-placed to deal with the challenges of urbanization, she said.

In Shimla in the Himalayan foothills, a refuge from the summer heat for Delhiites since colonial times, the state government is creating a city-level water agency for the first time. For a city where taps ran dry over the summer, that could prove a step in the right direction, Gulyani said.

Still, Shimla has a population of about 200,000, while Delhi is more than 100 times the size, with national, provincial and city administrations all having a say in how the capital is run. And while those who can afford it may visit Shimla to enjoy the mountain air, there’s no escape from Dehi’s smog for most of its inhabitants.

“It’s totally haphazard, mad growth of population with no regard” for the effects on the environment and health, said Arvind Kumar, a surgeon at New Delhi’s Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, who has seen a surge of lung-cancer cases among non-smokers due to pollution in recent years. “There was just massive growth, growth, growth.” – Bloomberg