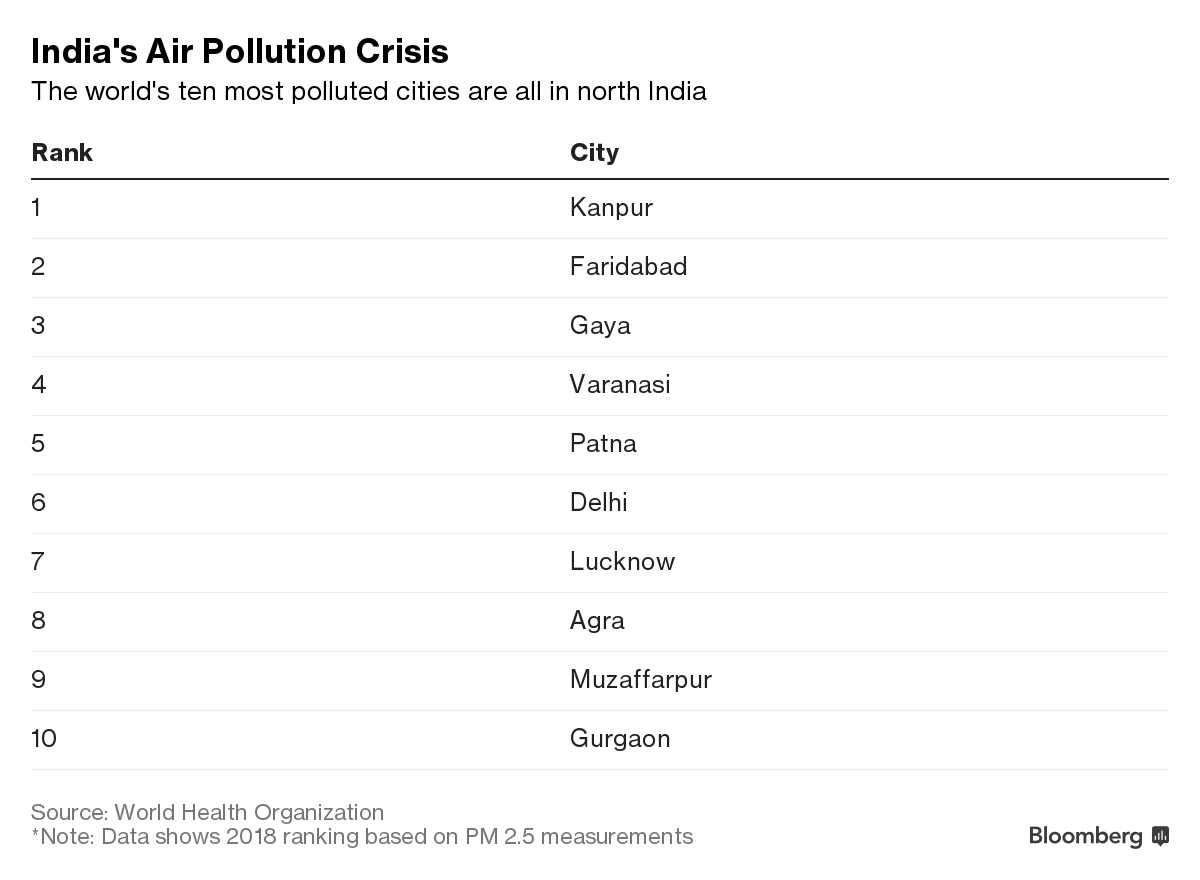

The sheer scale of India’s toxic skies is making progress in the fight to reduce pollution difficult.

New Delhi: As black smoke pours out of an ancient scooter that’s been pulled over, a khaki-clad New Delhi transport official issues a fine to its rider: 100 rupees, about $1.42. It’s hardly Hollywood stuff, but this is progress in a city of 20 million on the front lines of India’s battle against the world’s worst air pollution.

India’s smog-shrouded capital has become a symbol of the country’s struggle to contain a deadly haze that kills an estimated 1.1 million citizens every year. The government has pledged millions of dollars and deployed extra teams to improve enforcement of existing environmental laws that include banning farmers from burning their fields. But the sheer scale of India’s toxic skies makes progress difficult.

“It’s an uphill battle,” says Varsha Joshi, the top official for power and transportation in the Delhi government. But, she adds, “there’s a feeling that we’re doing something important.”

Between mid-October and mid-November, Joshi’s team issued roughly 16,000 fines for “visible pollution,” compared to less than 6,000 in the same period last year, and around 8,000 tickets for drivers failing to have an up-to-date pollution certificate — double last year’s figures. She also helped shut down the coal-fired Badarpur power plant on Delhi’s outskirts.

While environmental activists say Prime Minister Narendra Modi needs to take more action on air pollution, powerful bureaucrats such as Joshi are in the driver’s seat for some of India’s less-visible measures to reduce smog.

But in New Delhi — a city caught between federal, state and local government responsibilities — coordination on even routine matters is slow. On Monday, the National Green Tribunal set up to rule on environmental issues fined the Delhi government $3.5 million for failing to curb pollution, according to news agency Asian News International.

Joshi’s request for 60 new cars for transport officers took 18 months to wind its way through the system, and she only ended up with 27. Her attempt to order low-floor buses for Delhi’s struggling public transit network stalled. Her follow up to procure standard-floor buses went all the way the Supreme Court after it was challenged by a disability activist. Delhi government spokesman Raghav Chadha did not respond to a call or texts for comment.

Still, Joshi says there has been progress, including a 14 per cent increase since October in the number of people getting pollution control certificates for vehicles. And there is greater political will to implement policies, she says, adding she hopes India can move toward hard pollution reduction targets, something China has already done.

“We’re now stumbling, moving toward a place where we understand what’s happening, if nothing else,” Joshi says. “My sincere hope is that next year we’ll be able to talk about quantitative targets, which still hasn’t happened. Till now, we’ve just been kind of begging the lord for mercy.”

Crop Burning

Outside of the city, there’s actual fires to put out. In the rush to plant the next wheat crop, north Indian farmers burn leftover rice stubble — sending plumes of smoke into the sky that foul the air in Delhi and dozens of other cities in northern India and across the border in Pakistan.

In the nearby state of Haryana, in a field of stiff rice stalks left over from the recent harvest, a group of 20 farmers gathered in late September to watch a tractor pull a basic-looking piece of farm equipment called a Happy Seeder. The machine plants wheat through the stubble, leaving the crop residue to rot, preserving soil moisture and reducing the amount of water needed.

“There was a whole lot of stubble in my field last year, so I had to burn,” says Dharma Vir, a 55-year-old farmer. “I’m going to experiment with the Happy Seeder this year. And if there’s a better yield, a better profit, I’ll keep using it.”

Sonalika Group, India’s third-largest tractor manufacturer, organized the workshop and donated two seeders and two other pieces of farm equipment to 25 Haryana villages. Costing $2000, the seeder is too expensive for most farmers, but the government — as well as companies like Sonalika — are making the machines available at local depots and stressed farmers can earn more money by using less fertilizer and water.

“You have to make them understand the economics,” says Lopamudra Priyadarshini, who heads corporate social responsibility at Sonalika unit International Tractors Ltd. “Indians don’t learn because of what I say, they learn because of what their fellow brothers do.”

Satellite Data

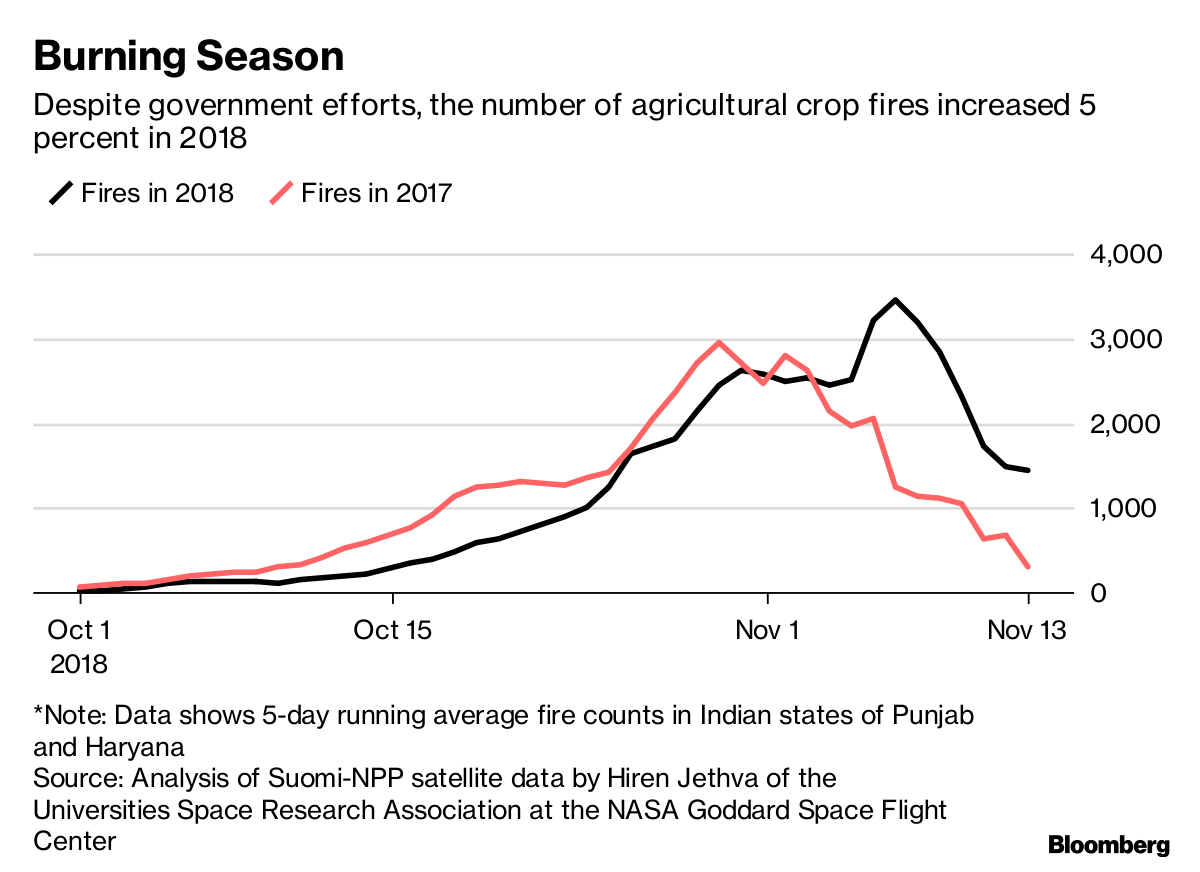

The central government has distributed about $85 million to the states to try and eradicate crop burning, according to environment ministry spokesman Gaurav Khare. But satellite data shows that amount has not made a difference — this year farmers have continued to set thousands of fires.

There were 5 per cent more fires this year in the peak burning season between Oct. 1 and Nov. 15 than there were last year, said research scientist Hiren Jethva of the Universities Space Research Association at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Apparently, the efforts and the amount dedicated to reducing the crop fires haven’t been effective,” at least according to satellite data, he said.

The central government can only do so much, Khare said. “The center cannot do everything on its own,” he says. “It’s a work in progress.” – Bloomberg