New Delhi: As the 2002 freeze on delimitation of Lok Sabha constituencies nears its post-2026 deadline, the possible perils of the population-based exercise for southern states is fast becoming a cause of public debate.

The issue was raised by Tamil Nadu MP and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) member Kanimozhi N.V.N. Somu in the Rajya Sabha last week, in the context of the devolution of funds to states on the basis of population. The MP’s statement came days before the Election Commission started the process of delimitation of assembly and parliamentary constituencies in Assam Tuesday. This follows the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) reported assurance, ahead of last year’s assembly elections in the state, that the exercise would be held in order to protect the “political interests of the people”.

The larger, national delimitation exercise has, however, raised concerns about the unequal representation of states in the Lok Sabha.

According to a paper published ahead of the last general election in 2019, if India’s Lok Sabha seats are redistributed across states after the delimitation exercise scheduled to be conducted after 2026, then states in North India may gain more than 32 seats, at the expense of southern states, which may end up with approximately 24 fewer seats.

Echoing the estimates of the paper, Somu argued last week that delimitation of Lok Sabha seats on the basis of population is unfair to the southern states, which have implemented family planning programmes better than the states in the north.

“Tamil Nadu is the only state which sincerely and successfully implemented the family planning programme proposed by the Union government,” Somu said. “South Indian states, particularly Tamil Nadu, have controlled their population growth to 6 per cent. In North Indian states, family planning was not implemented with sincerity and due respect. As a result, there is an increase in the population of states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.”

She added: “It is absolutely ridiculous and very unfair that states which successfully implemented family planning are penalised, and states that are reckless are being incentivised.”

According to the 2019 research paper India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation by policy analysts Milan Vaishnav and Jaimie Hintson, for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh alone would gain as many as 21 seats in total, while Tamil Nadu and Kerala taken together will lose 16 seats, if the delimitation is carried out according to the 2031 Census — the earliest scheduled after 2026.

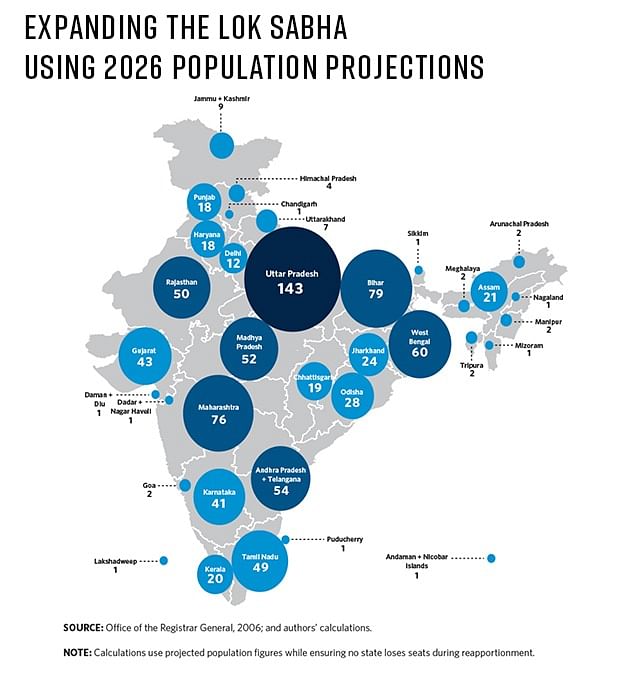

The paper further projected that if the strength of the Lok Sabha is increased after the exercise (according to projected population figures), the lower house would have to have a strength of 848, to enable accurate representation, according to the proportion-to-population principle. In such a scenario, Uttar Pradesh would have a whopping 143 Lok Sabha seats (as opposed to the present 80), while Kerala would still have the 20 seats that it has now.

Delimitation is the process of demarcation of the boundaries of parliamentary or assembly constituencies. According to the Constitution, the number of seats allocated to each state in the Lok Sabha is dependent on its population. The Constitution also calls for the reallocation of seats after every Census. However, because of decisions taken by subsequent governments and Parliaments — starting with Indira Gandhi in 1976 and then Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2002 — the last such exercise was carried out after the 1971 Census. According to the Constitution (84th Amendment) Act, 2002, there is a freeze on readjustment of constituencies till the first Census after 2026.

Vaishnav and Hintson’s research illustrated why the long-overdue delimitation of India’s parliamentary constituencies may set off a political crisis of epic proportions in the country.

Not only do states in the south stand to lose out in terms of the number of seats, but the scheduled delimitation and reallocation of seats may also end up giving more power to parties that have their strongholds in the north, such as the BJP. The exercise will also affect the division of seats reserved for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SC/ST) in each state.

Despite the challenges, however, Vaishnav and Hinston argued that it’s time for the exercise be carried out.

To minimise issues, the two have proposed some remedies in their paper — such as increasing the total number of seats in Parliament to ensure that no state loses the seats it already has. This proposal may also be something that the Union government is considering, going by reports that the architects of the new Lok Sabha, being built as a part of the Central Vista, have been asked to plan for at least 888 seats in the Lower House.

ThePrint looks back at some of the projections of the Vaishnav-Hintson paper, in view of the current debate over delimitation.

Also read: What is delimitation and why it is so crucial and controversial in J&K

India’s crisis of representation

The number of seats in the Lok Sabha is constitutionally decided according to the principle of proportional representation. Article 81 requires that each state receive seats in proportion to its population. These seats are thereafter allocated to constituencies of roughly equal size.

The Constitution also currently requires that the number of Lok Sabha seats be capped at 550. In order to ensure proportional representation, Article 82 of the Constitution calls for the reallocation of seats after every population census.

The current strength of the Lok Sabha, 543, is based on the Census of 1971 — data that’s over five decades old data. The delimitation process has been frozen since.

In 1976, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, during the Emergency, suspended the revision of seats until after the 2001 Census. In 2001, the Parliament extended this freeze until the next decennial census after 2026, scheduled for 2031. Therefore, if Lok Sabha seats are reallocated after 2031, legislators and policy makers will have to factor in demographic and political changes in the country over the past 60 years.

This attempt at fixing representational status will also be looked at through the critical lens of electoral politics.

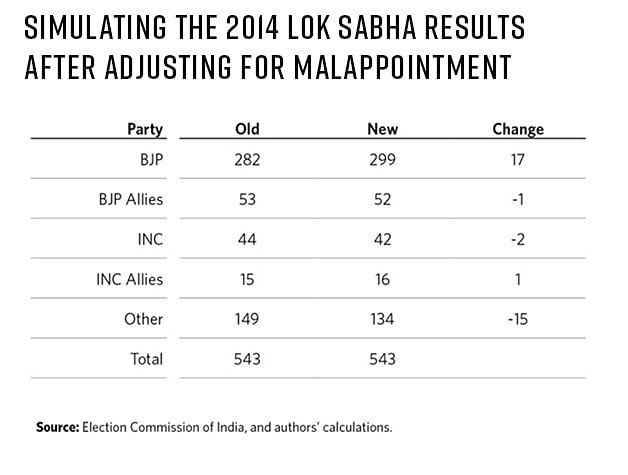

For example, Vaishnav and Hintson’s paper projected that if India’s Lok Sabha seats and their distribution across states accurately represented the country’s population according to the 2011 Census, then the BJP would have had 17 more seats in the Lower House than it did when it came to power in 2014. Most of these extra seats would have come to the BJP at the expense of regional parties from the south.

Over-representation in south, under-representation in north

The chief challenge in this exercise, by all accounts, will be the South-North divide.

Vaishnav and Hestin used previous research by political scientist Alistair McMillan to draw this conclusion. In his 2000 study, McMillan had used a methodology of calculating delimitation — the Webster method — to estimate the malapportionment in the Indian Parliament according to projected data for the 2001 Census. The Webster method is used to calculate the delimitation of electoral constituencies. It is the system that most closely satisfies the ideal of one-person, one-vote, one value. It does not favour allocation of seats according to the size of states and is instead based on the number of seats of average population size that each state could return.

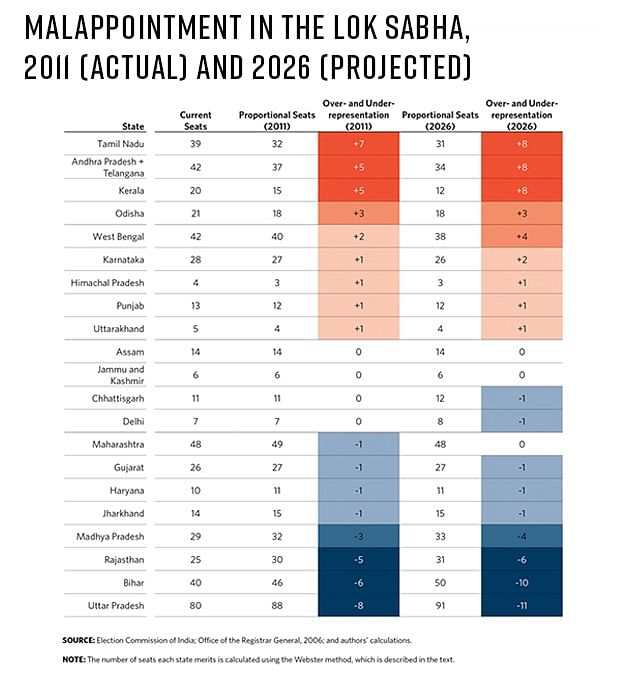

According to McMillan, in 2001, the over-and-under representation in the Lok Sabha was already so stark that — if the proportion-to population-formula were followed — Uttar Pradesh would have had seven more seats in the House and Tamil Nadu would have lost the same number.

Vaishnav and Hestin have used the same methodology to project total Lok Sabha numbers based on the 2011 Census. Thereafter, by using the 2001 and 2011 Censuses, the two have projected state population figures till 2026 and then repeated the calculation. This has shown that by the time the next delimitation exercise can be carried out after 2026, the severity of malapportionment in the Lok Sabha will be a lot worse.

The reason for this is that the present seat allocation in the Lok Sabha does not account for the drastic shift in India’s demography over the past five decades, especially with regard to the differences in the rate of population growth in South and North India. These vast differences in population growth rates are a “product of disparate — albeit slowly converging— fertility rates”, stated the paper.

While states in the south have controlled population growth better, the North Indian states have seen a population boom, explains the paper. This means, over time, in terms of proportion to population, North Indian states should have more seats in Parliament than South Indian states.

“What struck me when I saw the numbers was how out of balance things have become. We are at a situation where there are several states in the south that are highly over-represented in terms of representatives per actual population and then states in the north that are under-represented. This is a kind-of violation of one-person, one-vote,” Vaishnav had earlier told ThePrint.

However, while the one-person, one-vote policy rules Indian elections, the southern states argue that they should not be penalised with less representation just because they’ve implemented population-control policies better.

“The popular saying is that if you don’t perform, you perish. It cannot be changed to if you perform, you also perish,” Kerala Rajya Sabha MP and CPI(M) member John Brittas told ThePrint.

He added, “The spirit in which this was discussed 25 years ago, that should prevail. Southern states should not be penalised for their success in population control because that was done as per the national policy that was envisaged.”

According to Vaishnav and Hestin, if accurate apportionment of Lok Sabha seats had been done in keeping with the 2011 Census, then four northern states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh) would collectively have gained 22 seats, while four southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu) would have lost 17 seats in the present Lok Sabha.

This trend is likely to intensify by 2026, according to population projections, which show that Bihar and Uttar Pradesh alone would gain as many as 21 seats together, while Tamil Nadu and Kerala together would lose 16 seats.

Lok Sabha MP from Tamil Nadu and Congress member Karti Chidambaram told ThePrint that he was in agreement with Somu and Brittas, and that the scheduled delimitation, if carried out in its present form, would weaken the federal structure.

“It is unfair to the southern states to redraw the boundaries according to population, which will keep us completely under-represented in Lok Sabha”, said Chidambaram.

“Electorally, it would imply that by winning the Hindi heartland, a national party can ignore the southern states. The southern states would get further ignored if this exercise is carried out in this form and it would weaken the federal structure,” he added.

Shift in political power

While such realignment of seats may fix representation in the Lok Sabha, it’s also likely to hand over political advantage to parties that are based out of northern states, such as the BJP. This has given rise to a debate in which some have questioned if representation according to population numbers should also include provisions for inclusion of those who are under-represented due to social factors.

Vaishnav and Hestin’s paper used population figures from the 2011 Census to reapportion Lok Sabha seats and thereafter re-imagine the electoral numbers for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. Assuming that the proportion of seats in each state won by each party does not change, the BJP’s majority in the Lok Sabha in 2014 would have increased from 282 to 299, largely at the expense of southern regional parties.

Another important shift in terms of electoral politics would be in the number of constitutionally reserved SC/ST seats in the south and the north. The number of SC/ST seats reserved in each state is in proportion to the population share of these communities in the overall population of the state. If revised according to the 2011 population figures, the Lok Sabha overall would have one more seat reserved for the STs and two more for the SCs, the paper pointed out.

However, the real political shift lies in how the total number of SC/ST seats in the Lok Sabha will be redistributed among states. Slower-growing southern states would lose reserved seats, while faster-growing northern states would gain them. All in all, the reservation status of 18 seats would change, claimed the paper.

However, Vaishnav said the country has “come to a moment” where the exercise cannot be stalled any further.

“This (is) a moment akin to the 1956 States Reorganisation Commission, which was a moment when we really had to think about what a grand bargain would look like, and how we address the question of a federal structure. If we consider some of these issues (the loss of seats by Southern states) together, there can be some kind of barter. For example, of course Kerala would not like losing relative share of power, but this upset might be offset if it could lock-in some kind of guarantees on fiscal transfers,” he had earlier told ThePrint.

According to the 15th Finance Commission’s formula for tax sharing among states, Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh were reportedly the biggest losers.

Possible solutions to delimitation dilemma

Vaishnav and Hestin have provided possible solutions to fix this problem of malapportionment. All of them, however, will require political will and for parties across the spectrum to work in tandem.

The first strategy that the two suggested was simply committing to a reallocation after 2031, and not causing any more delays in the exercise owing to political or policy difficulties, or both.

Their second strategy is one that follows from McMillan’s hypothesis, which is to increase the number of seats in the Lok Sabha. This has two advantages, according to them — first, MPs would then represent smaller constituencies, which would help expedite governance, often delayed due to the massive population pressure on poorly-staffed administrative agencies.

Futher, the two explained, it also seems to be a more politically feasible option, as politicians are more likely to agree to the number of seats increasing in certain areas or states, as opposed to letting go of seats in geographies where they wield more power.

However, McMillan proposed that the Lok Sabha “expand just large enough that the most over-represented state does not lose any seats under reapportionment”. When projected to 2026 by Vaishnav and Hinston the numbers show that the Lok Sabha would then have to have a strength of 848, with Uttar Pradesh having 143 Lok Sabha seats (as opposed to the current 80), while Kerala would still have the 20 seats that it has now.

The third solution that Vaishnav and Hestin proposed is to reform the composition of the Rajya Sabha — known as the House of States. While the Upper House is constitutionally meant to be a house where states can advocate for themselves, it has become common practice over the years for non-residents of a particular state to hold Rajya Sabha seats of that state. This practice became even more common after a 2003 amendment removed the link between a representative and their state, by doing away with the domicile requirement which mandated that MPs be residents of the states they represent.

The two suggested that the Rajya Sabha be made representative of states and state interests so that one house in Parliament can give equal voice to all states.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Delimitation shows India’s democracy continues to struggle in the face of Kashmir challenge