Girnar, Junagadh: Prabhat Chinabhai Bhavnath, a herdsman in his early 40s, saw the forest of Girnar — draped across the folded hills of Gujarat’s Junagadh district — come to life in front of him.

“My family has lived here for generations. When I was a child, there was nothing here. The face of the hills was bare. All the trees had been cut. There was no jungle to speak of,” he said. “Then things started to change.”

The past three decades have marked a period of transformation in Girnar. Once left balding by relentless deforestation, grazing, encroachment and mining, it now grows over 500 different species of plants and trees.

In 2008, part of the forest became a wildlife sanctuary that is home to, among others, the majestic Asiatic Lion, a threatened animal that has seen its numbers dwindle on account of poaching and habitat fragmentation.

Of the 672 lions in India, approximately 48 reside in the Girnar forests, about 40 kilometres away from the more famous Gir lion reserve, the only other abode of the Asiatic Lion.

The rare predator is believed to have migrated back to the area right after conservation efforts began in 1992. Before that, it was last seen here in 1963.

The Girnar is better known for the temples that dot its landscape.

Lakhs of Jain and Hindu pilgrims across the country flock to the hills around Mahashivratri and the Girnar Parikrama to seek enlightenment and salvation by walking around its five peaks.

But for those who live at its foothills, the forest itself is no less sacred, and its transformation a blessing. The return of the animals has given rise to instances of animal-wildlife conflict — one woman described seeing her dog being taken away by a leopard — but residents largely speak of a peaceful coexistence and improved lives.

“The forest is linked to our livelihoods. We bring our cattle here to graze, and when the forest prospers, we prosper too,” said Bhavnath.

Also Read: On World Wildlife Day, a look at some of India’s success stories

A forest degraded

Gir and Girnar were once part of a major forest ecosystem that was slowly eroded by economic and development activity. Eventually, the two were isolated from each other, and Girnar was recognised as a separate forest in 1980.

Deciduous and rich in teak, the forest lies within the enclosure of Girnar’s peaks, covering about 178 square kilometres.

The throngs of pilgrims who visit Girnar contributed to its degradation over the years by leaving behind garbage.

But there was a problem bigger than that. For generations, the 39 villages surrounding the forest depended almost entirely on firewood to earn a living.

Jamalbhai Bachubhai Pathan, 60, was one among thousands who earned a living chopping trees for firewood.

“There used to be a space allotted for people to cut. Back then, the forest officers would take money from us and only then allow us to cut. We would sell 10 kg of wood for Rs 10 in the market. It was how we earned our living. There was nothing else for us to do at the time,” he said.

It was the legacy of a practice known as the kathiyara system. Before Independence, people would pay a small tax at a gateway, known as the Paj naka, before being allowed to go into the forest to cut wood, said Dr K. Ramesh, the district’s chief conservator of forests.

“The system continued after Independence and ended in the 1980s, but woodcutters would still go into the forest. All the trees had been cut, and the land was barren. The forest had been totally degraded,” he added.

In 1992, however, a wind of change began to blow as Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer Bharat Lal arrived In Junagadh as deputy conservator of forests, a role he served until 1994.

In a report prepared at the time, Lal wrote that Girnar had been by the 1980s “ruthlessly exploited by illegal tree felling”.

He noted other factors too. “Due to a ban on liquor in the state and the proximity of the forest to the adjacent city, bootleggers started using Girnar, and its various resources, such as water dead and dry fuel wood, and undulating terrain, for making illicit liquor,” said the report. “Uncontrolled grazing and illegal cutting of trees for timber and bamboo, coupled with encroachment and mining caused rapid degradation of the forest.”

Lal wasted no time in putting together strict measures to ensure the forest wasn’t destroyed further. The department secured funding from the World Bank’s Integrated Forestry Development Project programme, and those who felled trees were offered alternative jobs.

“They were extremely strict about it. They threatened and beat us into leaving the forest,” said Pathan, who was given compensatory land outside the forest, upon which he started to farm.

“In retrospect, they did the right thing. When we would cut wood, we would toil for little money. Now we get good rainfall, there’s a good water conservation network. We’re grateful for how the forest has been restored,” he said.

Bringing back the lions

Girnar’s revival offers many lessons when it comes to restoration. One of the primary ones is that the restoration of a forest begins, at its most granular level, in the soil.

“Many people think of tree plantations when they think of restoring a forest. But that’s just one part. Our primary motivation is to protect the soil from erosion. If the soil is healthy, everything else will fall into place,” said Sunil Barwal, deputy conservator of forests in Junagadh.

A key ingredient in the prevention of soil erosion is water. The natural structure of the hills has defined the passage the water takes when it rains. Typically, water runs down the face of the hills without stopping, robbing the soil of essential nutrients.

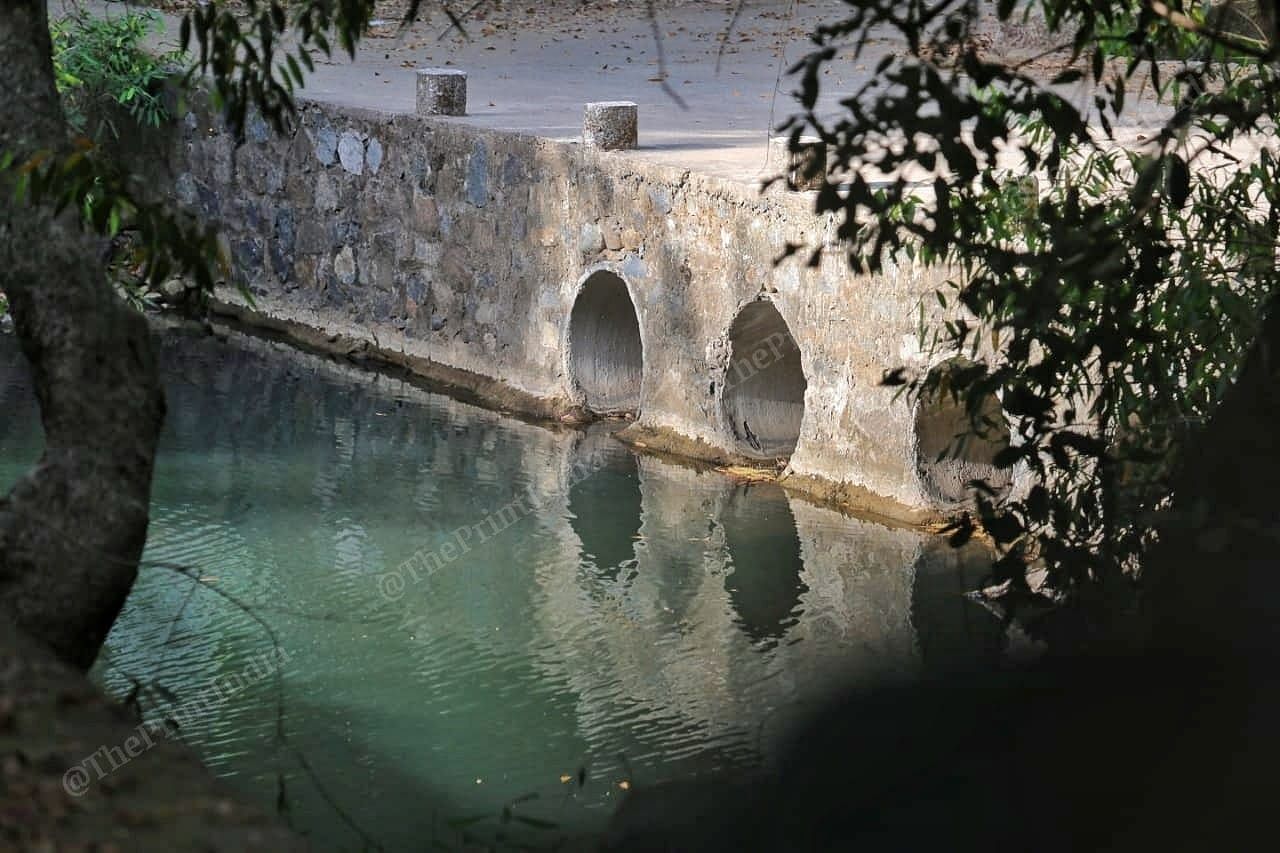

The solution to this lay in building check dams — structures that take the form of basins dug into the ground, to trap water that can then seep into the soil. Over a hundred check dams were built into the sanctuary, which fuelled the natural growth of trees.

A devastating drought that hit the nearby Gir forest reserve in 1987 also sped up the reformation efforts.

“The massive drought that hit Gir national reserve in 1987 led to migration of herbivores and cattle into the Girnar forest reserve. When water became available for the animals to drink, the lions started to migrate too, seeing that it was a suitable habitat,” said Ramesh.

Although the forest hadn’t regrown, the results of the restoration work began to show soon after they were started. The first Asiatic lion was spotted in the Girnar forest in 1993, and the numbers haven’t stopped growing since.

Also Read: From widespread hunting to wildlife conservation — how Manipur district took 180 degree turn

Living with lions

Inside the forest — not too deep — two young lions around three years old, named Nuro and Gogro after their caretakers, laze about under the cover of some trees. They are nearly concealed by the yellowing leaves of the season, and take no notice of the human spectators who came especially to see them.

“Lions don’t consider us natural prey. They don’t make an attempt to sneak up and attack people. Leopards are far more dangerous in that sense,” said Deepak, a forest guard who has been with the department for nine years.

Given the small size of the sanctuary, the 48 lions in Girnar are about as many as it can comfortably accommodate. Instances of infighting — when male lions fight for their territory, sometimes to the death — are beginning to surface, say forest guards, but they aren’t as rampant as in the Gir reserve, where over 600 lions live.

Instead, a growing area of concern is conflict between the wildlife and humans. Between 2020 and 2021, two people were killed by wild animals (other than lions) in Girnar.

“Unlike a lot of other sanctuaries, we don’t have a buffer zone between the wildlife sanctuary and revenue land. They border each other, so it’s a challenge we have to consider,” said Barwal. “But we have made sure every household can contact us in case we need to intervene when there’s been an interaction with humans.”

Lions seem to have a preference for cattle. From 2020 to 2021, there were 209 cases of cattle kills by lions, for which their owners were compensated between Rs 3,000 (for small animals like goats) and Rs 30,000 (for larger ones like buffalo). A total of Rs 15.25 lakh was disbursed in compensation, according to data with the forest department.

“Yes, lions do attack our buffalo, but this is natural and not a deterrent for us,” said Lakhanbhai Charan, 55, who lives in Rawat Sagar village that shares a fence with the sanctuary.

“We aren’t scared, and if there is a predator in our backyard the department always comes to help. Our only complaint is that the compensation we get for the cattle kills should be higher.”

A few kilometres away, in Vagnahiya village, Labubehen Bhaliya, who grows corn and chillies in her small patch of farmland, said, for now, it’s a peaceful coexistence.

“One of my dogs got picked up by a leopard. I saw it, but I couldn’t do anything,” she added. “It’s okay. It’s the way things are over here. We’ve learned how to live with the jungle, and we wouldn’t have it any other way.”

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Covid proved that India needs a dedicated Wildlife Protection Authority