Chennai: In the 1920s and early 1930s, when the classical dance now known as Bharatanatyam was on the brink of a complete wipeout, it was one landmark music institution that helped revive and rebrand it. That was the Madras Music Academy, the home of Carnatic music.

“In 1932, the Madras Music Conference of the Music Academy passed a resolution to rename sadhir (sadhir attam, or court dance) into Bharatanatyam. The idea was to remove the unsavoury connotations of the previously existing names like sadhir, dasi attam, etc. The ‘depraved’ Sadhir entered a ‘respectable’ home of Brahmin elites,” writes Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) professor S. Jeevanandam in a 2016 research paper, ‘Exploring Bharatanatyam: A Reformed Dance Form of Devadasi Tradition in the 20th Century’.

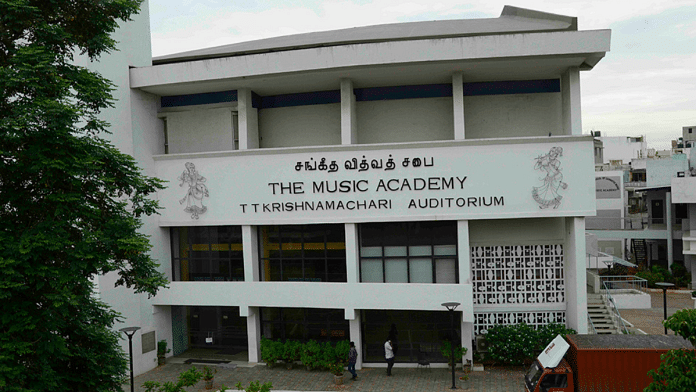

Today, the 97-year-old academy is caught in a blazing row after announcing its decision to award the Sangita Kalanidhi — its most prestigious award, often regarded as the highest accolade in the field of Carnatic music — to T.M.Krishna, a vocalist known to challenge caste and religious boundaries with his art. At the centre of this controversy is the Margazhi Festival of Dance and Music, an event that Krishna, also a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay award, will preside over by virtue of winning the award.

Seven Carnatic vocalists have withdrawn from the event and the Music Academy Conference 2024 — both in December — after accusing Krishna of trying to polarise the music world along caste and communal lines.

The academy has defended its stance, calling a letter written by singers Ranjani and Gayathri, who first objected to Krishna’s presence at the event, “unwarranted and slanderous assertions and insinuations verging on defamation”.

For the academy, which is often viewed as a symbol of Brahminical absolutism, this stance is notable. The row has also left the Tamil Brahmins divided — while some support the protesting musicians, others criticise their stance as perpetuating caste hegemony.

“The problem for those creating this uproar is that an institution that is supposed to represent ‘them’ has gone and sided with the enemy,” writer-columnist Sujatha Narayanan told ThePrint. “The teacher who once made the errant student (Krishna) stand outside the class is now awarding the very same student. And the class is not happy.”

Also Read: How TM Krishna got under the skin of the Carnatic music fraternity

Patron of arts, rebranding Bharatanatyam

According to its website, the academy emerged as an offshoot of the All India Congress Session held in Madras in December 1927.

“A music conference was held along with it and during the deliberations, the idea of a Music Academy emerged. Inaugurated on 18 August, 1928, at the YMCA Auditorium, Esplanade by Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, it was conceived to be the institution that would set the standard for Carnatic music,” the website says, adding that its objective was to “give to music its rightful place in our national life”.

Renowned musicians including Bidaram Krishnappa, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar, Palladam Sanjeeva Rao, and Pudukkottai Dakshinamurthy Pillai served as members of the academy’s first expert committee.

According to Chennai-based Carnatic vocalist Sivapriya Krishnan, there’s much that the institution deserves credit for.

“The academy has played quite a role in Carnatic music. It was started as an academy, the name itself denotes its higher purpose, beyond just being a sabha or institution that holds music concerts. The founders wanted to set up an academy with the objective of propagating music, where it would be sung, performed, discussed, researched, and documented,” Krishnan said.

Today, the institution is known not only for its music festivals — the Margazhi festival being the most prominent among them — but also for its role in collecting, archiving, and publishing an array of musical compositions, maintaining a library and a museum.

The academy’s annual music conference, held during the Marghazhi music festival, is attended by well-known musicians from around the world.

Apart from periodically holding workshops and helping musicians, the music academy also runs the Advanced School of Carnatic Music, an institution offering many courses on Carnatic music and education. In 2011 and 2012, the school signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society (SIFAS) and Kalakruti School of Music, Melbourne, for academic support.

But the music academy’s earliest — and arguably its most notable — achievement was when it helped preserve Bharatanatyam in the early 1930s. Then called Sadir attam (court dance), the dance form was part of the devadasi system — a now-banned religious practice under which prepubescent girls are offered to gods for marriage and are frequently sexually exploited — and faced severe backlash from Periyar’s reformist Self-Respect Movement.

Jeevanandam writes: “The Self-Respect Movement propagated for the restriction of the performance of devadasi women. In 1928, the Youth Conference of Isai Vellalar at Chidambaram passed resolutions that the musical system of devadasi was degraded and recommended for reform. In 1930, the Women’s Conference asked the devadasi performers to leave their degraded profession, such as prostitution and it appealed to the people not to engage in nautch parties.”

A subgroup within the Vellalar (agrarian) caste, Isai Vellalars were traditionally performers of classical dance and music in Hindu temples and courts. This community, lower in the traditional hierarchy than Brahmins, comprises groups such as melakkarars (tavil artistes), nayanakarars (nadaswaram artistes), nattuvars (those who teach and conduct a dance recital), and Devadasis (women dancers).

By the late 1920s and 1930s, the process to revive the dance form had begun with the academy at the helm. The first step was rebranding — the Tamil sadhir or dasi attam gave way to the more Sanskritised ‘Bharatanatyam’.

However, this move too came under criticism, with many calling it the “Brahmanisation” of the art form, which has increasingly come to be dominated by Brahmin artistes over the past century. “While there were many discussions on renaming the dance form, it is difficult to find the exact person who coined the word Bharatanatyam,” writes Jeevanandam.

Overlooking musicians & question of inclusivity

Even before the T.M. Krishna row, the academy has had its fair share of controversies over the Sangita Kalanidhi award. For instance, violin maestro Lalgudi. G. Jayaraman famously declined the award, miffed that it came “too late” in his career.

The academy later bestowed the Lifetime Achievement Award upon him during its 80th anniversary celebrations in 2008.

The cultural lodestar also saw another controversy in 1978, when it announced the Sangita Kalanidhi award for Telugu Carnatic vocalist, musician, and composer Mangalampalli Balamuralikrishna for his contributions — including inventing ragas. Veena maestro S. Balachander opposed this move, saying that ragas can’t be invented.

“Many stalwarts like Lalgudi Jayaraman, Ramnad Krishnan, Madurai Somu, MD Ramanathan, T.N. Rajaratnam Pillai were not given the award. But even that didn’t become this controversial,” Carnatic vocalist Sivapriya Krishnan said.

In 2018, the #MeToo movement hit the academy, forcing it to bar seven musicians — N. Ravikiran, O.S Thyagarajan, Mannargudi A. Easwaran, Srimushnam V. Raja Rao, Nagai Sriram, R. Ramesh and Thiruvarur Vaidyanathan — from the Marghazhi festival.

But the biggest allegation against the music academy concerns its lack of inclusivity. Chennai-based Dalit activist and author Shalin Maria Lawrence calls it a citadel for “high-society Brahmins”.

“It (the academy) holds relevance only within the 3 percent (Brahmin) community. That too, only elite Brahmins. I know poor Brahmins who cannot even think of going and buying those expensive tickets,” Lawrence told ThePrint.

Tamil isais (songs) are less commonly performed at the academy and Telugu keertanas are more popular. “And most of the artistes performing there are Brahmins,” she told ThePrint.

According to Narayanan, what’s needed is the “democratisation” of the academy and its music.

“I await the day when a generation can follow Carnatic music, not because it’s the dhwani (note) they are used to hearing in their family homes but because it’s an art form that deserves attention and expression. It will be the day when an audience that has people from all economic groups can learn the art form irrespective of religion, caste, or subcaste from genius musicians who exist amongst us today,” she said.

However, vocalist Krishnan disagrees with the allegation that the academy isn’t inclusive.

“It’s about, talent, hard work, and persistence. It’s not and should not be about a group of people. The art is the most important thing. Anybody who has unwavering faith in the art does well in life,” she said.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: 1 yr on, Kalakshetra still fractured. ‘Passive aggressive’ jibes, no student on POSH panel

The Dalit activist and author Shalin Maria Lawrence uses eliminationist rhetoric of the DMK and DK – using 3% as a code for Brahmins. She is also indignant, like the DMK xenophobes, that Telugu songs are performed. Readers need this context to understand the language being used.

Learning and mastering carnatic music requires co considerable time evotion and little wealth. Practice makes the person perfect. Previously it was guru shysia traditon Nowa days govt musical colleges, University degrees, ph.d s which can be secured by any music interested person… So this kind of anti Brahmin bashing is totally unwarranted…. There are thousands of Brahmins family. Which had no access to any type of arts like others. Only people living in towns upwards had the access. This Sadhir turned into respectable sentences is simply meaning less. It was undeniably fact that Brahmins nourished the arts and culture and Isai vellars contributed marvellously… This proving art has no caste barrier. Hence I expect to stop spreading this canard. Carnatic music soul is Bhakthi, devotion to God…. Both are inseparable… Unwittingly TMK too indulged and proved it by rendering in mosque and Christian stage. TMK is such a pathetic soul and he is turned a person of negativity.