New Delhi: India’s latest price support policy for farmers places more emphasis on keeping consumer inflation in check than reflecting the new normal of rising cultivation costs and soaring food prices following the Ukraine war, a reading of the numbers show.

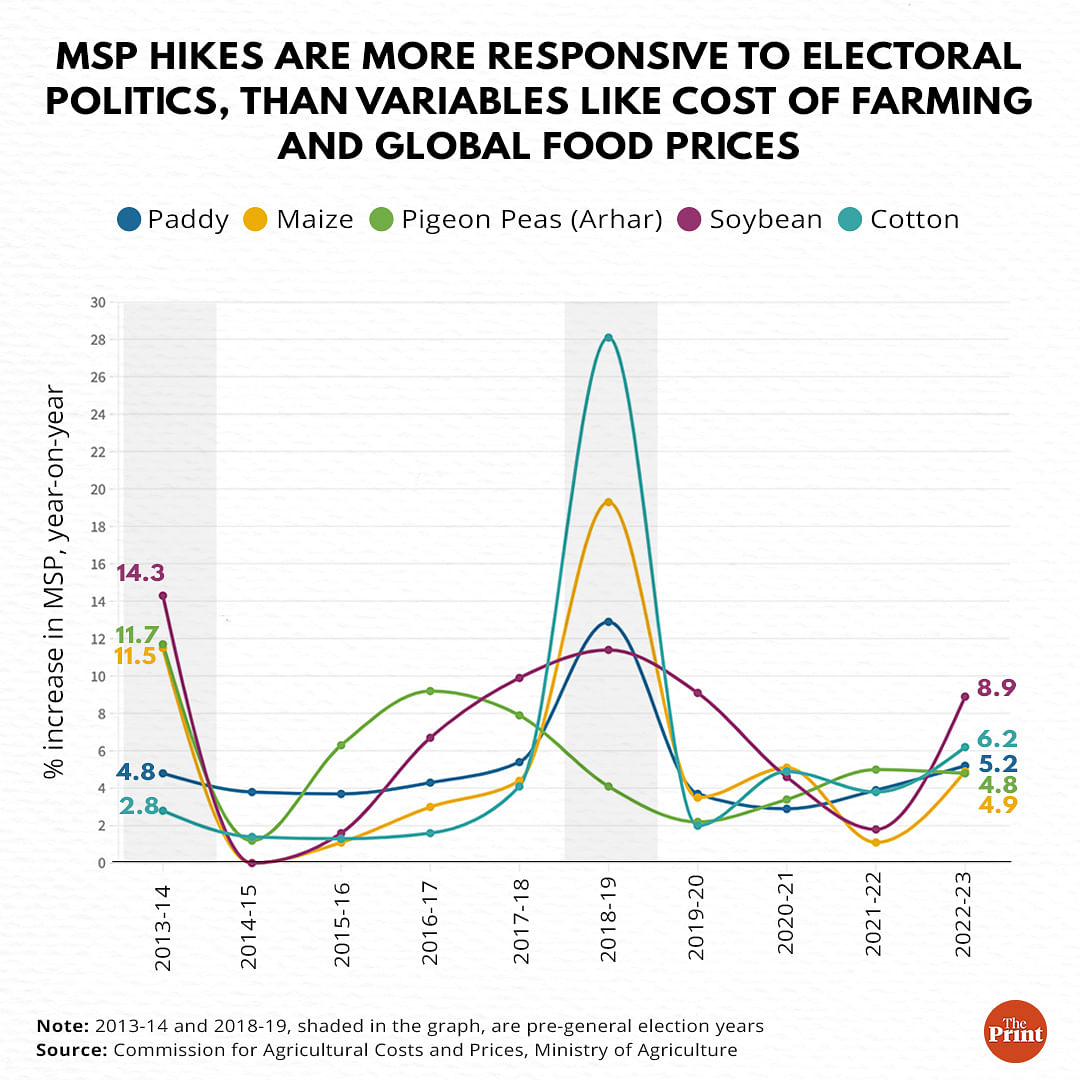

The Narendra Modi government Wednesday announced minimum support prices (MSP) for 14 crops — including grains, pulses, oilseeds and cotton — to be planted during the June to October Kharif season. On an average, support prices were raised 6 per cent, the highest in four years, but significantly lower than the hike announced during the pre-election year, 2018 (about 13-20 per cent).

The average increase in MSP this year is lower than the 6.8 per cent increase in estimated cost of production on account of higher seed, manure, labour and energy costs. Further, for several varieties of oilseeds and cotton, the announced MSPs are significantly lower than current market prices, rendering support prices ineffective.

According to experts ThePrint spoke to, the new MSP regime does little to incentivise farmers to grow more rice, the main cereal crop, at a time when wheat supplies are stretched. For oilseeds, where India is severely dependent on imports, farmers are expected to take a cue from the market and increase planting.

The modest 5.2 per cent increase in paddy MSP is worryingly inadequate, said Avinash Kishore, research fellow at the New Delhi office of the International Food Policy Research Institute. “It is not enough of an incentive for farmers to plant and produce more rice in a situation where wheat is in short supply and there is some uncertainty around the monsoon,” Kishore said.

“Remember, rice is a different ball game. The world depends on India for rice.”

The size of India’s wheat harvest is estimated to be at a multi-year low in 2022 following a record-breaking heatwave in March, which prompted the government to ban exports last month and replace a portion of wheat supplied to food subsidy schemes with rice. Unlike wheat, where it is a marginal player, India contributes about 40 per cent in volume terms to the global rice trade.

Consumer food inflation surged to a high of 8.4 per cent in April while inflation in wholesale prices came at a 27-year-high of 15 per cent. But a muted hike in MSP may not be enough to keep food inflation in check. That’s because a part of the inflation is beyond domestic factors — due to high dependence on import of edible oils, fuel and natural gas which pushes consumer prices up.

Also read: India’s sweet spot in hoarding wheat looks shaky. Ukraine war means new concerns for Modi govt

‘India’s MSP decisions behind the curve’

The moderate increase in support prices despite soaring commodity prices rests on a hope and a prayer, said Himanshu, associate professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

“It hopes that by keeping support prices low, food inflation can be tamed. The prayer is that the monsoon will play a supporting role,” Himanshu said. “The problem is, the government might face a situation similar to wheat where the MSP was lower than market price, leading to a sharp drop in procurement.”

The latest price policy announcement, according to Himanshu, proves that MSP decisions are not dynamic and are “behind the curve”.

For instance, the Kharif price policy report prepared by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), which forms the basis of the MSP announcement, was finalised on 31 March, more than a month after Russia invaded Ukraine — an event that upended global food markets and led to spike in prices across the board. Yet, the CACP report, which takes effect when Kharif crops are harvested in October, does not take into account the impact of the ongoing war and how it drove up food and energy prices globally.

The Kharif price policy has no bearing except for two out of 14 crops, said Pushan Sharma, director at Crisil Ltd., a ratings and research firm. “In the past three years, only paddy and cotton have seen some meaningful procurement (45 per cent and 27 per cent of total production, respectively). Since current market prices for cotton are substantially higher than the support price, farmers will only take a price signal from the paddy MSP.”

The data on annual hikes in MSP over a decade shows paddy support prices rose the sharpest, by 13 per cent, in 2018. That was the last Kharif before farmers, who form a sizable chunk of India’s population, voted in the general elections held in 2019.

It is likely the government will announce another sharp hike in support prices in 2023, months ahead of the general elections in 2024.

“It’s a case of food policy held hostage to electoral politics. And the delay could cost India dearly on the cereal front,” warned Himanshu.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: Great Indian wheat export mystery: Turkey didn’t reject for quality, Israel bought it, ITC says