The IL&FS crisis exposed the problems plaguing India’s bond markets, and they continue to struggle. The regulator is trying to keep a strict watch and reduce losses for millions of households.

In this context, the role of rating agencies is evident. Rating agencies failed to detect discrepancies in companies such as IL&FS, Dewan Housing, Zee and Reliance Communications as they grew over time. This led to sudden downgrades, which, in turn, required funds to sell their downgraded bond holdings.

The safety of savings in mutual funds, pensions, provident funds and insurance policies is related to regulations for measuring risk levels of bonds that funds invest in. The role of regulation is to protect small, retail consumers and their savings to the extent possible. Small, retail investors put money in provident funds, mutual funds, insurance companies etc., and do not know or understand where fund managers are investing their savings.

Rating agencies have a huge say

Investment guidelines are created to reduce the risk that fund managers may take in their quest for higher returns. Many funds cannot hold low rated or risky bonds under their investment guidelines. Liquidity for most corporate bonds is low as there are not many buyers and sellers. As a consequence, sudden downgrades cause difficulties. Bond prices fall and consumers suffer huge losses as funds find it hard to sell bonds at short notice. Securities regulator SEBI’s focus has, therefore, turned to rating agencies.

Under the present system, investment guidelines often say how much should be invested by funds in AAA-rated, or AA-rated companies. These ratings are provided by credit rating agencies, which rate bonds according to their risk profile. Credit rating agencies, therefore, have a huge say in which companies can borrow from the market and at what cost. Companies that borrow pay rating agencies to rate their bonds.

This model is riddled with problems that are not unique to India. The same issues were seen in the US at the time of the Lehman Brothers crisis. Highly-rated bundles of housing loans were suddenly downgraded to junk status, which led to a debate around the role of credit rating agencies in the 2008 global financial crisis.

The problem is not easy to solve as investors are averse to paying for ratings. Proposals for independent rating agencies have also not taken off. The world has so far stuck with the issuer-pays model.

The incentive of the borrowers who get their bonds rated is always to get a better rating. A higher rating lowers the cost of borrowing. Whether a rating agency genuinely rates a bond high as it fails to detect trouble in its balance sheet, or whether it knowingly gives a company a higher rating is a matter of conjecture. It is reported that four rating agencies are currently being probed by the Serious Fraud Investigation Office (SFIO) for their rating of IL&FS’ finance subsidiary.

Also read: SEBI moves to curb excessive speculation by regulating derivatives

Tighter norms

After the sudden and sharp downgrade of IL&FS bonds in September 2018, SEBI introduced new, tighter norms for credit rating agencies. One company has been downgraded almost every month since November 2018. Asset managers also shun companies, related companies and group companies that look risky. This has a feedback loop as the value of the bonds of these companies falls.

This story also feeds into the health of the NBFC (Non-Banking Financial Company) sector. NBFCs normally borrow money in the bond market. They constitute about a third of the non-government bond market borrowing.

Starting with the trouble with IL&FS, DHFL and Indiabulls, weaker NBFCs found it difficult to borrow. Some NBFCs were found holding bonds of their own group companies. Others were holding bonds of illiquid or risky companies.

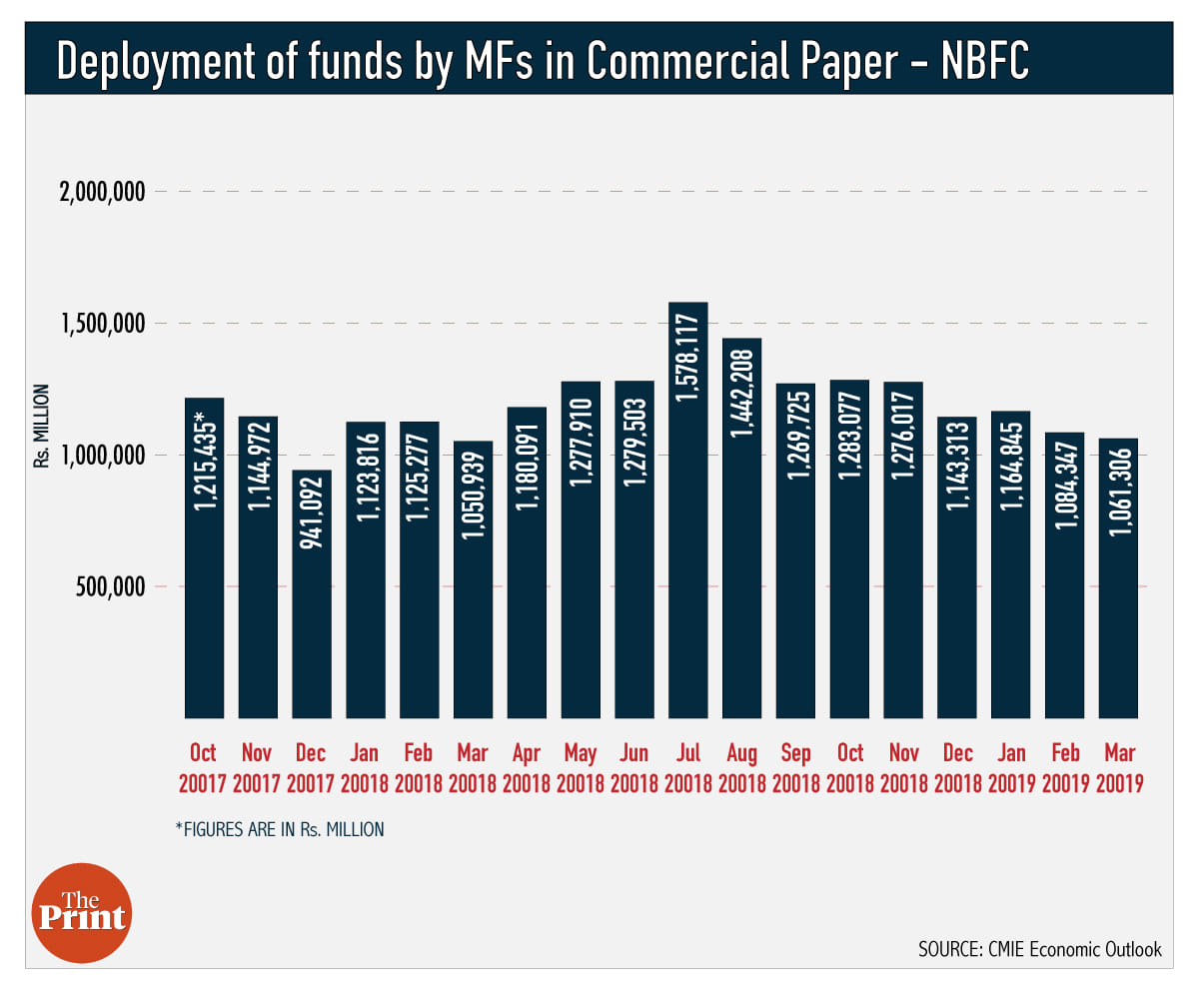

Overall, there has been a sharp decline in borrowing by NBFCs after the IL&FS downgrade. As the figure shows, in July 2018, mutual funds were investing Rs 1.58 lakh crore in short term bonds of NBFCs. By March 2019, this number had fallen by more than a third to about Rs 1 lakh crore.

In the last few weeks, promoter loans against shares have become an issue in the bond market. It seems many mutual funds entered into an agreement with the Essel Group not to sell promoter shares as they were required to do after a default, on the grounds that selling shares of the defaulting company would have hit share prices. This violated the terms of Fixed Maturity Plans through which the money was invested. The extent of loans against shares in mutual funds could be the next source of problems in the bond market.

Need for reform

While tightening regulations for credit rating agencies is a step in the right direction, it will not be enough to solve the problems of India’s bond market. There is a need to build deep and liquid markets. The reform of the bond market requires an integration of the government and corporate bond market infrastructure with regulation, as well as an independent government debt manager.

There is a need to bring all markets for bonds, equities, commodities, currencies and derivatives under the securities markets regulator as proposed by various expert committees such as the committee on Mumbai as an International Financial Centre and the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission. SEBI’s actions are to be appreciated but broader bond market reform requires legislative reform and amendments of the powers given to regulators.

Also read: In IL&FS crisis season, why you should be worried if your PF money is with exempt trust

The author is an economist and a professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. Views are personal.