New Delhi: Authorities are on high alert over Niphah infections in Kerala as five cases have been reported this monsoon season from a wide geographical area in separate spillovers, a trend not seen since the first outbreak in 2018.

In May, a 42-year-old woman from Mallapuram district, who has since been critically ill, was confirmed with the infection, which is understood to reach humans from fruit bats, commonly known as flying foxes.

But starting this month, 4 more cases—two each from neighbouring Mallapuram and Pallakad—have been diagnosed with the infection. The two districts have large and continuous forest cover. Of the four cases, two have already succumbed to the infection, while the other two are critically ill and hospitalised.

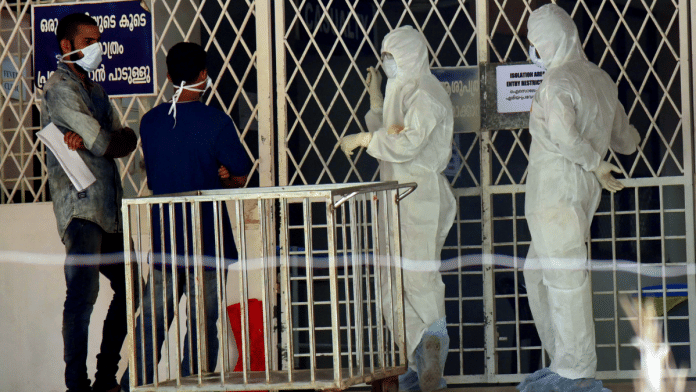

Additionally, 571 people from five districts who came in contact with these four patients have been put under isolation, while 27 identified as “high-risk” contacts.

Public health specialists in the state and outside point out that while Kerala is seeing the sixth outbreak of Nipah virus, there is a possibility of higher viral shedding of Nipah among the bats as compared to previous years.

In all the previous outbreaks, there was a primary or index case, which remained either a standalone case or led to cluster cases in close family members of medical personnel treating them, pointed out Dr M.G.Deepak, head of community medicine and public health researcher at Karuna Medical College in Palakkad.

“But the trend this year indicates that bats could be shedding a higher load of virus—though it needs to be confirmed through scientific studies—due to stress such as deforestation and this is not a good sign,” Deepak told ThePrint.

Prior to this year, Nipah outbreak had been reported in Kerala in 2024, 2023, 2021 and 2019 after 2018—the biggest one so far which claimed 17 lives. All of them were close contacts, including several medical personnel, of a single index patient.

The fact that the cases have been reported from an area spanning roughly around 60 km has also pushed almost the entire administration in two districts towards containment measures while four other neighbouring districts are on high alert, sources in the health department said.

ThePrint contacted Kerala health minister Veena George over phone calls for the government’s outbreak management. This article will be updated if and when a response is received.

Also Read: Health diagnostics is a game of ‘molecules & money’. Amazon has just entered the race

Frequent strikes in Kerala

Nipah is a zoonotic virus—transmitted from animals to humans—but can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly between people. It is one of the deadliest pathogens known to infect humans, as it kills nearly 75 percent of those infected.

In 2022, the World Health Organisation (WHO) put Nipah virus on its list of priority pathogens for the first time. Scientists have been concerned about the virus’s potential to cause a global pandemic as it is capable of human-to-human transmission.

The solace so far in the current outbreak, highlighted Deepak, is that there is no evidence of this transmission route despite the virus’s capability to become air-borne.

During the first recognised outbreak in Malaysia, which also affected Singapore, most human infections resulted from direct contact with sick pigs or their contaminated tissues. Transmission is believed to have occurred via unprotected exposure to secretions from the pigs, or unprotected contact with the tissue of a sick animal.

Nipah’s first two outbreaks in India were reported from West Bengal. The most lethal was the first outbreak, in 2001 — when 66 cases, the highest so far, were recorded in the eastern Indian state and 45 fatalities.

In 2007, the disease claimed five lives in West Bengal. There was, however, a gap of over a decade before the virus struck humans again, this time in Kerala in 2018.

While there has been no Nipah outbreak in West Bengal after 2007 despite a nearly annual outbreak in neighbouring Bangladesh, Kerala has been seeing an episode almost every year. The southern state’s dense tropical vegetation provides a natural home for fruit bats which are carriers of the Nipah virus.

Those infected with the pathogen in the beginning develop symptoms such as fever, headaches, myalgia or muscle pain, vomiting and sore throat, though very few can actually stay totally asymptomatic as well. The initial signs of the disease can be followed by dizziness, drowsiness, altered consciousness, and neurological signs that indicate acute encephalitis.

Some patients can also experience atypical pneumonia and severe respiratory problems, including acute respiratory distress and encephalitis and seizures occur in severe cases, progressing to coma within 24 to 48 hours.

A senior virologist with Indian Council of Medical Research- National Institute of Virology (ICMR-NIV) pointed out the outbreak over the last several years has been triggered by eating contaminated fruits and vegetables, through body fluids, excretory material, saliva, and secretions of infected animals or fruit bats.

“The natural source of the Nipah virus are fruit bats. The understanding is that rapid urbanization and encroaching the original cores, where fruit bats stay, is possibly causing the disease to spike over to humans. In the current outbreak, however, the spillover dynamic of the virus is not fully understood,” the scientist added.

Though there is evidence of Nipah virus being present in bat populations in at least nine states and one Union Territory—Karnataka, Maharashtra, Bihar, Assam, Meghalaya, Tamil Nadu, Goa, Kerala, West Bengal and Puducherry—their spillover in humans in Kerala has been linked with eating pattern or links between animals and humans, mainly due to cultural reasons.

“Fruit bats typically don’t fly long distances but deforestation and climate change bring bats closer to humans. It’s possible that bats in areas (where the outbreak is being reported from) carry the virus and get transferred to humans due to either consumption of infected fruits, sap or bat meat or handling of dead bats,” the ICMR scientist explained.

‘Good response but need to do more’

Kerala’s response so far has been exemplary, with the identification of the source, declaration of containment zones, immediate contact tracing of those who might have had close physical contact with the known cases, isolation and quarantining of suspected cases, and testing of contacts, experts told ThePrint.

“The state’s Nipah protocols were implemented immediately, even before final confirmation of the virus was obtained. These are all sensible steps,” said Gautam Menon, dean, research and professor of physics and biology, Ashoka University

Others said that the health seeking behaviour and health care utilisation pattern in case of the viral outbreak seems to be saving the day for Kerala.

“The 2018 outbreak was an outlier. The rest were probably more contained due to health care seeking behaviour and utilisation in Kerala as people are playing a major role in containment,” Deepak said.

In the state, he pointed out, the alert or suspicion levels are high both in public and private sector hospitals and suspect cases eventually end up in tertiary care hospitals—unlike in Bangladesh, where deaths happened at home or peripheral clinic levels.

However, public health specialists also cautioned that the acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) surveillance in Kerala needs strengthening. “Each spillover can lead to a cluster outbreak. As we are seeing now, containing four separate spillovers simultaneously is a big test for the health care system,” Deepak said.

Also, there has not been enough scientific efforts put in to understand study behaviour patterns which may be triggering the viral spillovers from bats to humans. “One such extensive study was done in Bangladesh and it identified how the viruses were getting transferred to humans. Eventually this led to evolution of practices which reduced outbreak incidences in the affected areas there,” Deepak said.

(Edited by Tony Rai)