New Delhi: After completing her MBBS from the Kannur Government Medical College in 2017, Dr Rahima Ali, 30, worked at a family health centre (FHC) in Cochin for nearly 7 months.

This stint, Ali told ThePrint, ended up defining her career path.

FHCs, a part of the Kerala government’s healthcare framework, are an extension of primary health centres (PHCs) and offer a broader range of services, while working towards providing holistic primary care to all age groups.

In 2022, when Ali was finally selected to pursue a Diplomate of National Board (DNB) course — equivalent to postgraduation (MS/MD) in medicine — her choice of stream was clear: Family medicine, instead of the much more lucrative paediatrics or obstetrics and gynaecology.

“I realised while working at the FHC that I loved helping and connecting with patients of all age groups — from children to the elderly — and catering to their healthcare needs,” Ali, who is pursuing DNB in family medicine from Lourdes Hospital in Ernakulam, said.

“Being a paediatrician or a gynaecologist would have limited my patient group. To become a family physician is to be the first-contact dependable and trustworthy doctor for the entire family — I want to become exactly that.”

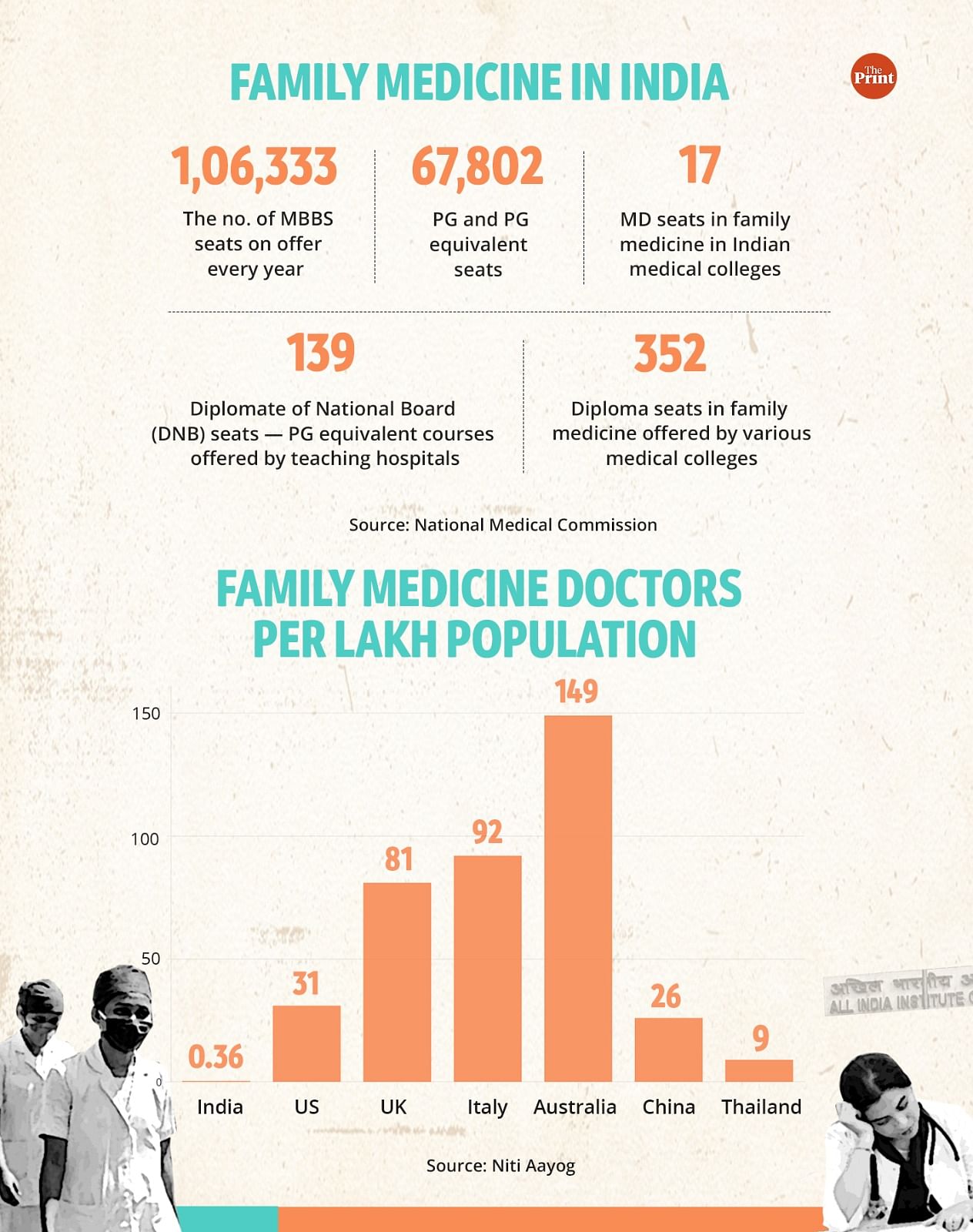

In a country that now boasts of over 1 lakh MBBS seats every year and more than 67,000 PG or PG-equivalent seats in medicine, the likes of Ali are an exception.

This is due to the limited chances on offer to pursue a course in family medicine, which is considered the backbone of the healthcare system in some developed countries like the UK and the US.

A doctor carrying all the necessary paraphernalia on the go, who would appear within minutes every time a person — a child with high fever, a woman experiencing pregnancy symptoms, or an ailing elderly family member — would need medical aid and a healing touch, used to be a ubiquitous presence in Indians’ lives, their centrality to the family depicted in many a yesteryear movie.

However, that tribe, over decades, has shrunk.

Despite recognising the importance of family-medicine doctors in the 1980s, India just has about 5,000 physicians in the field — or just about 0.36 per lakh population, against 81 per lakh population in the UK and 31 per lakh population in the US, according to Niti Aayog data accessed by ThePrint.

Dr Raman Kumar, president of the Academy of Family Physicians of India (AFPI), a network of about 1,700 doctors, said that, for decades, the medical regulator and the health policymakers had veered the system towards superspeciality, while turning the focus away from family physicians.

He cited statistics to back his claims. There are just 17 PG seats in family medicine in medical colleges across India, and only 139 DNB seats in hospitals (DNB courses are offered by teaching hospitals).

This, despite the fact that the government, on several occasions, has pledged to promote and facilitate postgraduate courses in family medicine while also promising to develop a competency-based dynamic curriculum for addressing the needs of primary health services, community medicine and family medicine.

“Yet, family medicine as a concept is not even taught in the MBBS curriculum as on date,” Kumar said.

While some hospitals have been offering DNB in the stream since the 1980s, the first PG course in the stream was launched in 2011 at the Government Medical College in Kozhikode, Kerala.

“The course, however, has not flourished in the manner it should have,” said Dr Resmi Menon, a teacher of family medicine in Kerala.

“It has meant that PG candidates look at it as a limiting career option, with no prospect of a government job or a career in academics.”

In many north Indian states, she said, those with a PG in family medicine, especially those who cannot practise independently, end up working as assistants to specialists in hospitals.

ThePrint called NMC spokesperson Dr Yogendar Malik for a comment on the issue, but did not get any response. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

Speaking to ThePrint, government officials denied allegations of neglect towards the field, saying efforts have been under way to equip the good old family doctor in line with changes in medical science.

Also Read: 80,000 seats, 7 lakh takers — inside story of why thousands of aspiring Indian doctors fly abroad

Long road to nowhere?

The need to promote family-medicine practitioners in India has been felt for a long time.

In 1983, a ‘medical education review committee’ — set up by the Union health ministry under the chairmanship of the late Dr Shantilal Mehta, a distinguished surgeon — recommended that “undergraduate (MBBS) medical students should be posted in a general practice outpatient unit in order to be exposed to the multidimensional nature of health problems, their origins”.

The committee also recommended that this specialty should be further developed so that an increasing number of students pursue higher study in the area.

The National Health Policy (NHP) 2002 noted that, in any developing country where adequate health services are not available, the requirement of expertise in the area of ‘public health’ and ‘family medicine’ is markedly more important than that for other clinical specialties.

The working group of the erstwhile Planning Commission for the 12th plan (2012–2017) estimated the projected need for specialists in family medicine (family physicians) as 15,000 per year for 2030.

This estimate found resonance in the 2017 NHP, which stressed the importance of family medicine as a specialty, and mandated the popularisation of programmes like MD in family medicine.

It also recommended that a large number of distance and continuing-education options be created for general practitioners in both the private and the public sectors, to upgrade their skills to manage the large majority of cases at the local level, thus avoiding unnecessary referrals.

These recommendations, however, never materialised in action.

Disappointed that the stated policy in successive NHPs was not being followed, the AFPI, in 2018, filed a PIL in the Supreme Court, asking for the implementation of family-medicine training. But it was directed to the Union health ministry and the erstwhile medical education regulator Medical Council of India (since replaced by the National Medical Commission).

In response to a plea by the AFPI, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), the same year, said that, under the National Medical Commission (NMC) Bill, 2017, the PG medical education board had been mandated to promote and facilitate postgraduate courses in family medicine.

It also said that the Graduate Medical Education Board under the NMC had been mandated to develop an MBBS curriculum featuring family medicine. ThePrint has a copy of the PMO’s reply.

The NMC Bill became an Act in 2019 and reiterated the message. But this June, after the commission released the Graduate Medical Education Regulations 2023, the AFPI found that it had no mention of the stream.

The association shot off a letter to the regulator, pointing out that the family-medicine component had been completely excluded from the draft — with the term not even mentioned in the 83-page draft. “This is not inadvertent or by default,” they said.

Speaking to ThePrint, Kumar of the AFPI said this “shows the intent of the NMC”.

“Earlier the MCI, and now the NMC, are just not interested in promoting family medicine either at the UG or PG level. The whole system continues to be skewed towards hospitals and superspecialists.”

But Dr V.K. Paul, member (health), Niti Aayog, said the government was clear in its intent to promote family medicine in India’s healthcare and medical education systems.

“Our ultimate goal and hope is to move towards a system in which the general-duty doctor in every PHC and CHC (community health centre) in the country is a competent family physician who can deal with a wide variety of illnesses that are commonly seen at community-level health centres,” he told ThePrint.

It is for this reason, he said, that in addition to PG and DNB courses, a two-year diploma course in family medicine had been started in several colleges — to produce clinicians who could offer patient-centred initial, continuous and comprehensive care to all age groups.

There are, currently, 352 such diploma seats available across the country every year, Paul added.

A senior official in the medical education division of the Union health ministry said the “doctor next door” of the past was just an MBBS physician — with no specialisation whatsoever.

“With time, however, medical science has changed tremendously and it was felt that on the lines of the West, the family-medicine doctor — who could cater to the primary healthcare needs of an entire family — should also be trained after the basic degree in medicine,” he said.

The official pointed out that, in the UK, in order to become a general practitioner (GP), an MBBS doctor needs to train for five more years. In the US, GPs have a residency programme in family medicine after their basic MD training (equivalent to MBBS), he added.

If there is acknowledgement that the system needs a drastic change to produce competent general practitioners, however, there are some moves that are seen as counterproductive too.

Dr Menon pointed out that some colleges had established joint departments of family and community medicine.

“These two streams are poles apart — one is concerned about looking at the clinical aspect of a family, the other at the health challenges of a community,” she added. “Conjoining the two helps neither.”

A senior NMC member who did not wish to be named said there were two main reasons why family medicine had not been promoted in a big way by the regulator yet.

“There is no separate department for this in medical colleges because there are nearly 20 departments in medical colleges teaching MBBS courses and the curriculum is already very heavy,” he said.

“Secondly, there is a crisis of faculty teaching the stream at PG level,” he added.

Kumar countered this. “In countries where the government wanted to promote the stream — they came up with alternative methods such as allowing practising doctors to teach the subject in medical colleges.”

Also Read: Distrust of Indian doctors isn’t new. Class-caste bias always ruled medical profession

Victim of systemic neglect?

According to Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, a public health specialist based in New Delhi, the healthcare system in India may have been, in a way, a victim of the success of a “good medical education system”.

“Since India produces good MBBS doctors and then specialists who do well in other developed countries, the argument has been that there is no need to promote generalists.”

This approach, he said, may have been problematic on several counts.

“A person going to an endocrinologist for diabetes or to a neurologist for a headache every time, for example, makes the healthcare far more costly,” Lahariya said.

“Also, a family physician is often far better at primary and preventive healthcare because they know the past and present medical history and lifestyle of a family and can guide the members better,” he added.

His suggestions find resonance in various studies.

“The family medicine practitioner can address a wide range of health issues, either through direct care or through referral to other specialties, thereby maximising the cost-effectiveness of the healthcare system,” said a 2022 study by researchers from the US, China and Morocco.

All hope, meanwhile, may not have been lost.

Last year, the government decided that all new All India Institute of Medical Sciences branches — except for AIIMS Delhi — will start a PG course in family medicine from the 2024 academic session.

“Every AIIMS institute will have at least two PG seats in the stream,” a senior health ministry official confirmed to ThePrint.

“This was possible after our continued push,” said Kumar. “But AIIMS are outside the direct control of NMC; we also want the commission to end the complete neglect of the branch.”

Some other experts, meanwhile, suggest an idea that may require a review of the whole medical education system.

“Family doctors and family hospitals — doctor-owned small nursing homes — are the need of the hour to provide affordable and ethical primary and secondary healthcare,” said Dr Ravi Wankhedkar, a senior member of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), the largest network of doctors.

Unfortunately, they are on the death bed, he said. But instead of specialisation in family medicine in the form of a PG degree, he added, the MBBS course should be strengthened and suitably modified so that a medical graduate can be confident enough to start a family practice.

“Increasing clinical training in MBBS is required,” Wankhedkar said “As of now, MBBS graduates are only focused on studying for the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET-PG) and more MD seats in family medicine will again just create another stream of specialists”.

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: India needs to innovate in filling vacant hospital posts. Building new AIIMS alone won’t cut it