Shahjahanpur/UP: The two men have spent the past 10 years attending long-drawn court trials, poring over lawyers’ documents, and fighting to prove their innocence.

But the two couldn’t be more dissimilar. One is Asaram, an 82-year-old powerful, white-robed, bearded, self-styled ‘guru’ from Gujarat—with a massive cult-like empire of devotion, donations, and dominion—convicted of raping a 16-year-old. The other, Singh, is a former devotee himself, but also the minor’s father. His life’s mission is to send Asaram to jail for life and throw away the keys.

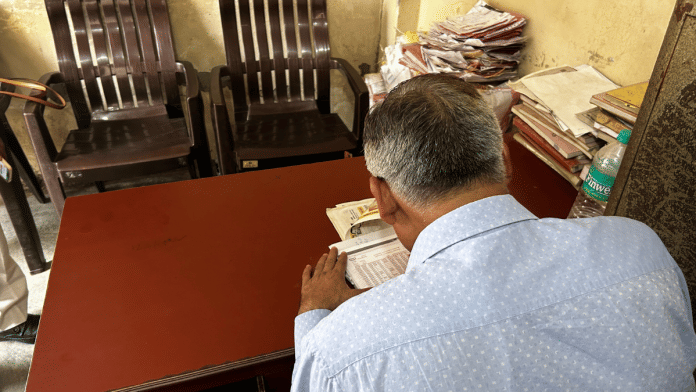

“It is no longer a court battle now, it has become a way of life. We are forever trapped in this,” Singh says as he gulps down an antidepressant, a fallout of the battle for his daughter’s truth.

Asaram has been taken to court in a clutch of cases involving rape, murder, land encroachment, and witness tampering. Convicted by a lower court of the minor’s rape in 2018 in Jodhpur and serving life imprisonment since then, Asaram has been appealing for the suspension of his sentence in higher courts — to no success. This time, he turned to the Rajasthan High Court on 10 July to plead for a 20-day parole to visit one of his ashrams.

It isn’t easy to take on an influential spiritual guru in India. And not everyone can do it either. The spiritual-industrial complex is, in all senses, a formidable mix of religion, politics, money, muscle power, and sometimes even the land mafia. So, when Singh launched a war against Asaram in 2013 after his daughter’s rape, the guru’s cult-like following descended on his family with a litany of counter-cases and an army of the country’s most powerful lawyers.

But what has undoubtedly been an audacious fight by Singh has also become a template for how to fight a Protection Of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act case against a powerful person who enjoys unmatched clout on multiple fronts – legal, social, and financial. At 61, he zealously guards his family’s privacy. A recently released film Sirf Ek Hi Bandaa Kaafi Hai, starring Manoj Bajpayee, brings back a wave of public attention to Singh’s family. It chronicles the legal battle, centering on Singh’s lawyer PC Solanki.

After he filed the complaint, Singh received hundreds of life-threatening calls from unknown men. They abused him, accused him of using his daughter to defame their guru, and tried to coerce him into dropping the case. Singh changed his phone number and stopped taking calls from unknown numbers.

But then, letters started arriving.

Angry Asaram devotees often threw letters with vulgar language against his daughter at his door. Strangers, pretending to be clients interested in his transport business, would knock on his door to intimidate him. But Singh didn’t give up.

In those five years, his trucking business went south, and he lost lakhs of rupees, developed severe health problems, lost the support of his friends and relatives, and became a man with a single-minded obsession. It wasn’t just that his 16-year-old daughter had been sexually abused by the adored family guru, he also felt personally betrayed. It is also a story of broken faith.

“We worshipped him like a god until he sexually abused my daughter,” Singh says, adding that he still feels disgusted every time he comes across a video of Asaram on YouTube. Even though he secured a conviction against Asaram in 2018 against all odds, his court battles are unending. It has been a David versus Goliath battle against the fury of Asaram’s loyal devotees who targeted Singh with multiple counter-cases of kidnapping, cheating, and criminal conspiracy in Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan. He has been running from one court to another for the past 10 years, trying to prove his daughter’s and his family’s innocence.

Singh’s daughter is now married and lives away from her parents, who reside in Shahjahanpur in Uttar Pradesh.

“This is the eighth case against me, my lord. I have been discharged in seven cases in the past. I am fighting against one man,” Singh spoke through Garima Bhardwaj, the lawyer who is representing Singh in another case, on a recent afternoon in Delhi’s Rohini Court.

A strapping man in a white kurta-pyjama with a towering presence, he stood in the court’s room number 207, flanked by three Uttar Pradesh policemen. After three hours of waiting and pacing up and down, he finally walked out — with a next trial date in hand.

It has been an endless cycle of court dates and snail-paced arguments in a world of staunch believers of Asaram — ultimately boiling down to a battle of faith versus a father’s fortitude.

The final hearing for Asaram’s appeal against his conviction in the Rajasthan High Court is expected to begin soon.

“If he is out, then we are jailed,” says Singh’s eldest son Omvir*.

Also read: Long wait for nursing dream—Shakti Mills rape survivor fights court red-tape, compensation

One man’s fight

Asaram’s trial is one of the most closely followed criminal proceedings in recent decades. It has been a virtual ‘who’s who’ in the Indian legal industry, with the 50 most powerful and costliest Indian lawyers coming to the guru’s defence—Ram Jethmalani, Salman Khurshid, Raju Ramachandran, Mukul Rohatgi, KK Manan, UU Lalit, Subramanian Swamy, Devadatt Kamat, and Sidharth Luthra, among others.

Singh’s lawyer, Solanki, on the other hand, stood alone on the other side – with no Mercedes Benz, fancy business cards, or Oxbridge accent. But he had a fire in his belly to bring down Asaram’s 40-year-old kingdom—the guru runs nearly 400 ashrams and more than 40 residential schools in India.

“The case has not reached its finality yet. Its appeal is pending in the high court. Once it reaches the Supreme Court, then it can definitely become a landmark in judicial history,” Solanki says.

In Sirf Ek Hi Bandaa Kaafi Hai, Bajpayee plays Solanki’s character and quotes Ramayana in the climax to highlight the nature of the crime committed against a minor girl and its impact on society.

He thundered in the courtroom that there are three types of sin in the world. The first two are forgivable to some extent, but there is no forgiveness for the third type of sin. Ravan had committed the greatest sin — kidnapping Sita, not as Ravan but as a saint.

“It left scars on the entire humanity for centuries to come. This man is Ravan. He has betrayed devotion, minors, and God. He used our God’s name to commit such a heinous crime. I claim the death penalty,” says Bajpayee in the movie. “To be hanged till death.” The court falls silent, and the fictional Asaram character, who is hiding behind a curtain, clutches his hands in fear.

Real-life events were equally dramatic. Solanki knew that a conviction against Asaram hinged on a watertight case by the Jodhpur Police, documentation for every counter-allegation by Asaram’s legal team, and consistency in Singh’s daughter’s account of what happened. Her statement would be scrutinised for inaccuracies so that the case could be discredited.

In a twist to the thorny case, Asaram’s legal team appealed in the lower court that Singh’s daughter was not a minor and that POCSO charges should be dropped. A fabricated certificate was produced to claim that she was a student of a UP school run by Swami Chinmayanand, but a Crime Investigation Department (CID) team from Rajasthan went to UP and confirmed she was a minor.

“Jodhpur Police’s investigation was imperative for the case,” says Solanki. From invoking relevant sections and collecting forensic evidence, everything was done in a timely manner.

In 2014, when the trial court was recording the statements of key eyewitnesses, Asaram turned to the Supreme Court for bail on medical grounds. Solanki flew from Jodhpur to New Delhi, his argument resting on the ‘merit’ of doctors from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) who he suggested could examine the godman. A committee of AIIMS doctors had travelled to Jodhpur to examine Asaram in jail and submitted their report confirming the guru did not need surgery. Not only was Asaram’s bail appeal rejected, but the top court also directed the police to register a case against the godman for misleading the court and levied a fine of Rs 1 lakh on him.

The Singhs remained steadfast in their commitment to get Asaram convicted. They had to stay in Jodhpur for months on end during the trial. It took around three months for the girl’s statement to be recorded and cross-examined. Singh underwent the ordeal for a month, while his wife’s lasted for two months.

“This was a way to financially exhaust us,” says Singh, adding that they had to bear accommodation and food expenses not just for themselves but the security personnel assigned to guard them. The family rented a hotel room in Jodhpur. One day, Singh opened the room to see a man book the room opposite theirs.

This feeling of helplessness was magnified in court.

“It was a very small room. Asaram sat on a chair behind a curtain. We were made to feel like we were the accused. My daughter was pinched and her foot was stamped (stepped upon) to distract her from recording her statements,” Singh says.

Her mother recalled a similar feeling of despair when they were made to wait outside while the girl recorded her statements.

“Our child needed us, but we had to wait outside. After she was done, we would cross a hoard of lawyers who hurled the worst kind of abuses at us,” she says.

Asaram filed around 40 applications during the case. “Barring three, he lost most of them,” says Solanki.

Also read: A rape forgotten—50 years ago, Mathura was denied justice. Then society betrayed her

A decade of worship and betrayal

As a young man growing up in a village in Haryana in the 1980s, Singh peeled off his military family to start a trucking business in Shahjahanpur.

“It was a backward district waiting to be transformed,” Singh recalls. Back then, he was among the three transporters in the town; now there are 15.

Although Shahjahanpur felt like “pardes” (foreign), Singh toiled to establish a flourishing business. He then brought his wife and three children along.

By 2001, he had built his own house in Shahjahanpur. He also renovated his house in his ancestral village.

“When you have enough on your plate, you seek a spiritual guru to guide you in life. I happened to meet a local lawyer once, who was Asaram’s devotee,” says Singh. The lawyer gave him a magazine published by Asaram, which was full of his spiritual teachings.

Singh and his wife were the third couple in Shahjahanpur to join the growing list of Asaram’s devotees.

The list of Asaram’s VVIP visitors included former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, PM Narendra Modi, former Madhya Pradesh CM Uma Bharti, former Rajasthan CM Vasundhara Raje, and former Chhattisgarh CM Raman Singh, currently BJP’s national vice-president. The minor girl’s parents started attending the guru’s satsangs. They enrolled their daughter and a son in Chhindwara Gurukul in Madhya Pradesh—one of the 40 gurukuls that Asaram runs.

“Asaram used to preach that we should donate 10 percent of our savings. I considered whatever he said as gospel truth. He made us believe that disbelieving him was equal to killing a cow,” says Singh. The family adhered to all the rules to seek his blessings on each Purnima or full moon night. Singh travelled the length and breadth of India, from Odisha to Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh to Uttarakhand, to catch a glimpse of Asaram.

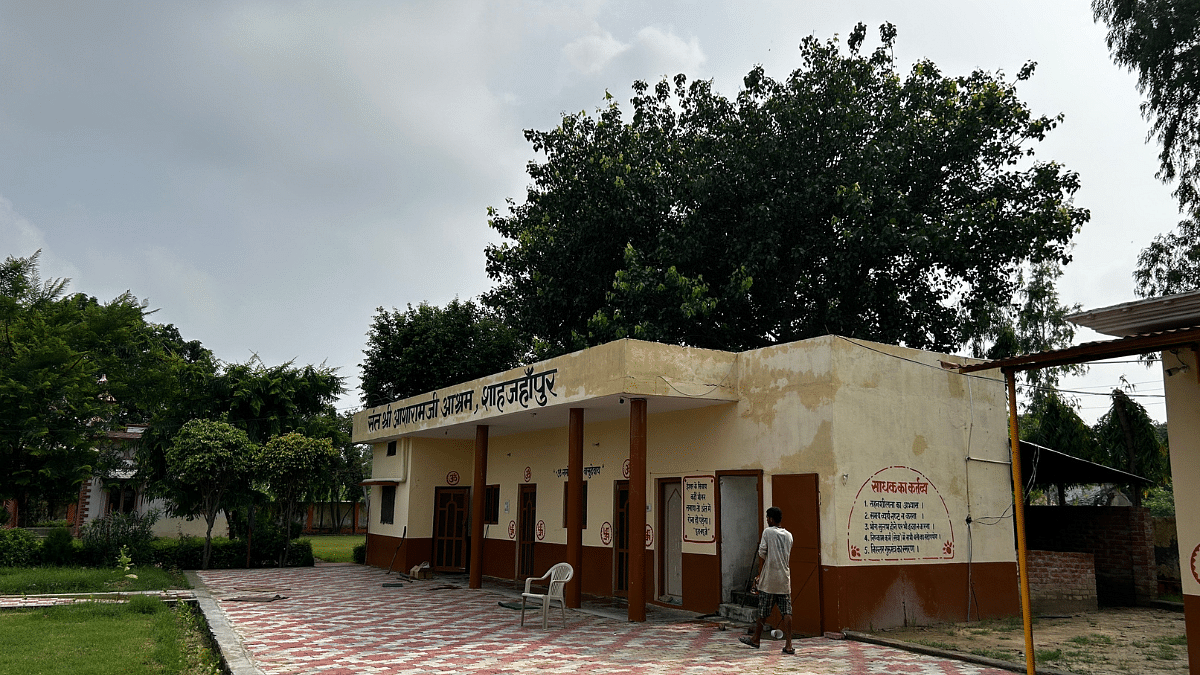

He even offered to build an ashram for the guru in Shahjahanpur. From purchasing a seven-acre land to constructing the building, planting trees, and installing an electricity connection, he did everything to make the ashram a grand success befitting Asaram.

The family started believing that Asaram wasn’t an incarnation of God — but God himself. The walls of their two-storey house adorned Asaram’s posters until 2013, when Singh’s unshakeable faith in his guru came crashing down.

“More than 50 of his devotees barged into our house after we filed that complaint and started heckling us to withdraw the case. And we would have been lynched that day if then-Shahjahanpur SP had not sent a police force,” Singh says. The day Asaram was convicted in 2018 by the court in Jodhpur, Singh’s house was transformed into a police cantonment.

“The city magistrate camped outside the house to protect us,” Singh recalls what his family had to face.

The year 2013

Singh’s daughter wanted to become a chartered accountant.

“She used to say that she will help her father in the business,” her mother Anita* says. But in August 2013, while she was studying in the Chhindwara Gurukul in Madhya Pradesh, she fell ill, and her parents were called in. The warden directed them to meet Asaram himself because they thought she was possessed by evil spirits.

The family followed what they were told. They reached Jodhpur on 14 August to meet Asaram. The following night, the godman raped her at his private quarters in the ashram under the pretext of treating her.

In her court testimony, the girl said Asaram removed her clothes and forced her to perform sexual acts on him while her parents waited outside, chanting mantras.

She was also threatened that her family would be killed if she told this to anyone.

“When she came out, she said, ‘He is not a god, he is a monster’,” her mother recalls, who didn’t know what had happened at the time. It was only later that she sensed something was horribly wrong. The family immediately left for their home in Shahjahanpur. Both parents distinctly remember that night when she finally told them that the very man they worshipped had raped her.

“She had tears in her eyes. I just put my hands on her head to convey that I believed in her,” Singh says, who then ripped out Asaram’s posters from the walls and tore them up one by one. The parents and daughter immediately left for Delhi in the car to confront the godman.

Asaram was preaching to thousands of people at the Ramlila Maidan. When the three of them tried to meet him, he shooed them away.

“I wanted to confront him by grabbing his beard in front of the crowd of thousands. I wanted to ask him why he did that to my daughter,” says Singh. But his daughter warned him that they would be lynched by the army of devotees if they dared to confront him in public.

“Let’s go to the police,” she urged her father. The closest police station to Ramlila Maidan was the one at Kamla Market. The police finally filed an FIR — a ‘zero FIR’ that can be filed in any police station irrespective of where the crime took place — on the intervening night of 19-20 August. The case was later transferred to Jodhpur.

The case marked the end of Singh’s daughter’s chartered accountancy dreams and life as she knew it. She could never go to college and was forced by circumstances to get her BA and MA degrees through distance education.

“The only time she stepped outside her home was to either give her testimony in the court or appear for her exams,” her mother says. “She was very intelligent, confident, and spoke English fluently.” Despite being trapped inside the house, she performed well in her final college year.

Solanki, too, vouches for her confidence, saying that she never wavered and stood by her truth throughout the trial.

In his book, Gunning for the Godman: The True Story Behind Asaram Bapu’s Conviction, Indian Police Service (IPS) officer Ajay Pal Lamba, who led the investigation in this case, wrote that every time his team had a low moment, they remembered her face. It would remind them that the 16-year-old wanted nothing but justice.

The book details how a PIL was filed to transfer the case to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Lamba, then DCP of Jodhpur East, told his team of 20 officers that it would be the biggest case of their lives. He was right.

Against the tidal wave of popular opinion, the Jodhpur Police arrested Asaram from his Indore ashram on 31 August.

Lamba is the latest person to be dragged into the high court and Supreme Court by a battery of lawyers representing Asaram for revealing details of the investigation in his book.

Anybody who calls out Asaram is subjected to severe social and legal intimidation, criticism, and bullying. There have been instances when strangers have stalked Singh and kept an eye on his whereabouts. Two men came to his home with a pistol, pretending to be customers.

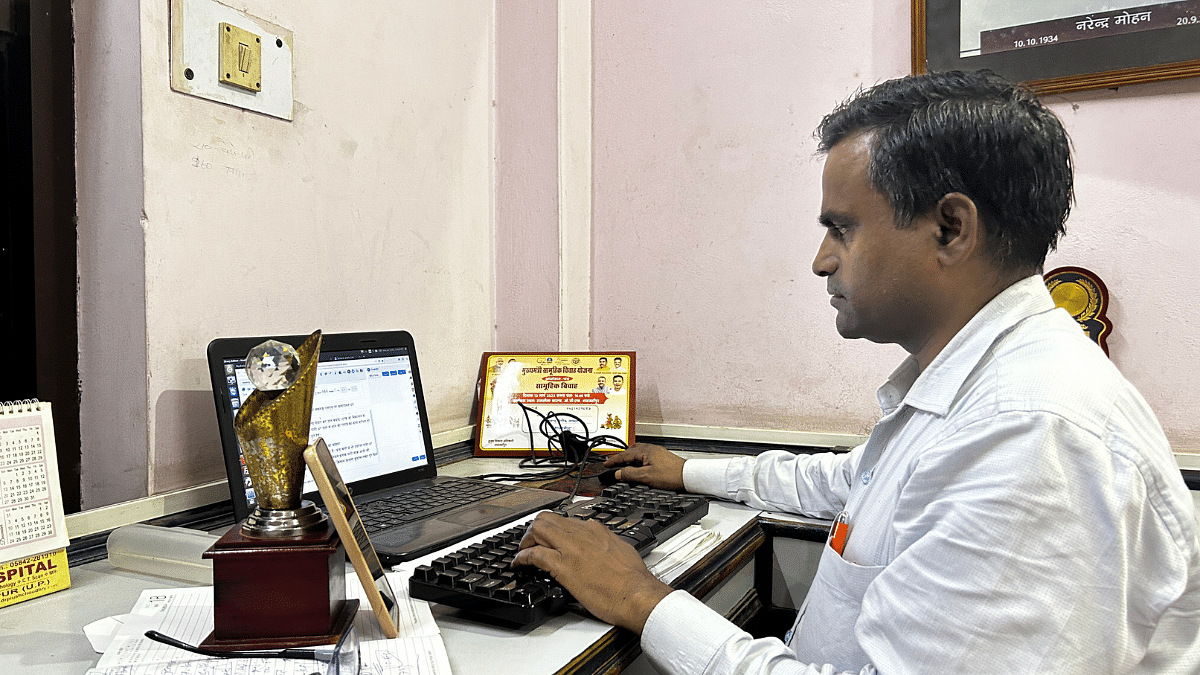

Narender Yadav, now an investigating journalist, started his career as a cub reporter at Dainik Jagran’s local edition when he met Singh.

“I used to cover the dharam-karam beat. Singh was associated with the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), and that’s how we got a few chances to interact. He appeared like a hard-working Jat from Haryana,” Yadav says.

Yadav later broke more than 287 exclusive stories on Asaram and his men at the peak of the case between August 2013 and September 2014. Then, on 17 September, he miraculously escaped a mysterious murderous attack. He was walking out of his office around 10:30 pm when he was accosted by two men on a bike. While the rider waited by the bike, the one riding pillion got down, walked toward Yadav, and slit his throat with a sickle.

Assuming Yadav to be dead, both men rode off. Yadav survived the attack but received 28 stitches on his chin and 42 around his neck. The following year, the local police identified his attackers when another witness and a close family friend of the Singhs, Kirpal, was murdered. One of the men, Kartik Haldar, who was arrested for Kirpal’s murder, was allegedly involved in the attack on Yadav as well. The trial is underway, and the second attacker is yet to be identified.

At least seven witnesses were attacked, killed, or went missing during the trial. Three, including Kirpal, were murdered, three went missing, and one person was stabbed inside the court premises in Jodhpur.

A family together in loneliness

The complainants, journalists, and witnesses lived in fear all those years. The unsaid warning was: If you revealed anything against Asaram, you will be made to pay.

Even now, Singh lives in constant fear of being falsely incriminated — for crimes such as rape. He does not meet strangers, especially women, alone, and chooses his words carefully when talking to the media.

“Any interview can land me one more case. I have been threatened that a case under Section 376 (rape) will be filed against me. Fake women journalists have knocked at my doors too,” says Singh. After all these years, he is exhausted.

The fight for justice has cost him greatly. People no longer drop by for friendly visits, and at the height of the trial, his transport business almost folded. Nobody wanted to work with him.

In this sea of isolation and loneliness, his daughter and family were his islands of refuge.

“My daughter’s marriage has relaxed me in ways that I could not imagine,” says Singh. In 2019, Singh found a “brave family”, willing to be associated with them. When the prospective husband was told about the case, he took a vow to not let his daughter down.

The family married her off in a grand manner before the entire village in their ancestral hometown. But just before the groom arrived on a horse at the wedding venue, a villager went up to him and whispered something into his ear. “Do you know she is the same girl?” he said to the groom, Singh recalled. But he paid no heed.

Those who had once threatened to organise a 12-village panchayat to pressure Singh to withdraw the case came to the wedding.

“She is proud of her father. He is a hero for us,” says the son Omvir*. He, too, had to sacrifice his ambitions at the altar of justice. He wanted to become a government officer but dropped out of the higher education cycle because his father was mostly travelling to appear in court.

After suffering (more than) 50 per cent losses in their business, Omvir is trying to get it back on track. Today, Singh is the president of the Jat Sabha in Shahjahanpur.

However, the girl’s mother confines herself to the second storey of the house. The ground floor is used for police security and the transport business, while Singh lives on the first floor.

Today, Singh has found solace in Hindu god Hanuman.

“This time, there is no middleman or godman,” he laughs.

Meanwhile, the city has moved on. At the Shahjahanpur ashram, which the couple built, satsangs are still held and Asaram devotees still flock to pray there. Ashram workers are told that ‘Bapu’ will be out of prison soon and that his time has come to bless the devotees, who distribute ashram pamphlets in the neighbourhood while maligning Singh’s daughter in passing. From their balcony, Both Singh and his wife helplessly watch their neighbours and friends go to the ashram.

And Singh has moved on from the faith. He doesn’t follow the ashram’s activities anymore. He hasn’t visited it since 2013.

There is, however, one question that he is curious about even today.

“Have the saplings grown into tall trees?” Singh can’t help himself from asking.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)