Daudnagar (Bihar): By day, all the young, able-bodied men in the village are lounging on their cots and napping. They are not at work. Women are out and about doing domestic chores. But something is amiss. There is an unusually large number of tractors lined outside homes, hinting at some form of economic activity.

As soon as the sun sets, the village transforms into a hub of busy men. By midnight, young men, aged between 15 and 30, are out on the streets. They climb onto tractors and head to the banks of the Sone River, which flows beside the village. The quiet night is broken by the steady khat khat khat of tractor engines.

The cattle, the dogs, and even those deep in sleep are used to the sound—it’s always the sand diggers in Bhagwan Bigha, a nondescript village with a population of around 1,200 in the Daudnagar block of Aurangabad.

At the riverbank, a 500-metre stretch comes alive as labourers dig into the yellow sand with shovels and even bare hands, loading their tractors. Nearby, bikes stand ready to escort the loaded vehicles back.

Night after night, while the rest of Bihar sleeps, they steal.

The story of loot doesn’t end here. The villagers have turned to another illegal trade—liquor production. Hidden behind the bushes next to the riverbank, nearly two dozen pots bubble away, brewing desi liquor that sells at dirt-cheap prices. The village’s economy, much like many other parts of the state, now rests on two pillars—sand and liquor. These industries run parallel, with a small section of the population employed in both.

Nearby villages have tried to fend off the mafia, but with little success.

“It was so rampant that you couldn’t even walk on the streets to bury the dead. There was no space on the roads to carry a procession,” said Arun Paswan, from the neighbouring village of Amrit Bigha. Villagers pooled resources to block roads, but the mafias then carved out a makeshift kuccha road leading directly to the sand.

In most illegal mining and liquor hubs, caste lines dictate control. The Yadavs, the dominant caste, run sand mining, while the Paswans, Mushars, and Mallahs are the primary liquor manufacturers.

The illegal system is more systematic than the government’s. It seems impossible to go back to what it was

-Kaushalendra Singh, Aurangabad-based businessman and former sand miner

Both industries generate unchecked black money amounting to hundreds of crores annually, driving widespread crime and corruption. Yet, as Bihar counts down to the high-stakes state elections this year, how the two mafias have corroded the economy, fuelled criminal politics, brought in a rural rot, and rendered its youth unemployable for at least a decade will hardly feature in campaigns.

The rivers have depleted, with children drowning in the dug-up holes, and the groundwater levels have drastically decreased. Every month, speeding, overloaded illegal vehicles claim the lives of hundreds of innocent people.

The alcohol ban brought in to keep women safe in 2016 by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar is now an albatross around his neck. Illegal alcohol is flowing freely, and precious sand is slipping through the state’s loose grip.

Both illegal liquor and sand mining feed into each other, according to Dr Bakshi Amit Kumar Sinha, a faculty member at the Bihar Institute of Public Finance and Policy (BIPFP) and a key contributor to state policy documents, including the Bihar Economic Survey.

“One sector’s black money is invested in another sector’s black money,” he said.

Ironically, sand smuggling continues unabated despite most alleged kingpins, including politicians, being jailed or facing ED corruption charges. Now the nature of the mafia itself has shifted.

Also Read: Bihar is on a sports gold rush. Rs 680 cr budget, big-ticket events, hunt for Olympians

Dark economy

The illegal operation starts at 2 AM and wraps up by 7 or 8 AM. Under the cover of darkness, villagers load at least 150 tractors with the precious sand, locally called baloo. Those with enough money buy or loan tractors, while others work as labourers.

Each tractor makes three trips, carrying a minimum of 4 tonnes of baloo per trip. With every load, the Bihar government loses revenue from 12 tonnes of sand, amounting to around Rs 2,000.

On the black market, sand sells for Rs 1,500 to Rs 2,000 per tractor—or just Rs 300 per tonne—far below the legal rate of Rs 3,000 to Rs 4,000. Each tractor-load of baloo is enough to construct at least one room.

The ripple effects of this black-market economy are felt well beyond the sandbanks. Entering state capital Patna from its outskirts, such as Bihta, has become a nightmare. Sand-laden tractors and trucks create endless traffic jams, sometimes stretching for up to 18 hours. All the sand mining hotspots—such as Arrah, Aurangabad, and Rohtas districts—are similarly choked by gridlock.

But what does flow easily and smoothly is illegal liquor. Anywhere in Bihar, a call to the right contact is all it takes for a bottle to arrive, whether it’s outside Patna’s Medanta Hospital or just two kilometres from the Chief Minister’s residence.

“Sab kuch sarkar ki naak ke neeche ho raha hai. Baloo churao ya daaru” (Everything is happening right under the government’s nose. Whether it’s sand theft or liquor), said Rakesh Kumar, a driver for a private agency. Illegal sand mining generates at least double the revenues of legal operations, according to mining department officials.

Mafia’s ‘humble’ new face

At the top of Bihar’s rural black market are the policymakers—MLAs and MLCs—collaborating with relatives to grease the wheels of the operation. At the bottom, labourers from marginalised castes toil endlessly. In the middle are the munshis, managers, and owners of tractors, JCBs, and Poclains, along with small-scale businessmen.

The money from sand, legal or illegal, runs into crores. On the legitimate side, Bihar earned Rs 1,558.16 crore from sand mining in 2023-24, almost twice the Rs 836.57 crore earned in 2018-19

While the state has increased its revenue through policy changes, surveillance, and political efforts, the sand syndicates have only grown stronger. The illegal market generates at least double the state’s revenue, according to the estimates of mining department officials.

Now, the state is trying to wrest back control. Deputy Chief Minister Vijay Kumar Sinha, who also heads the mining department, has taken an aggressive approach—touring mining hotspots by helicopter, suspending corrupt officials, and introducing measures like GPS tracking, mobile apps, and CCTV at riverbanks.

“The government is committed to increasing revenue while turning nature’s resources into a boon, not a curse,” he declared last month.

We have installed CCTVs to monitor activities 24 hours a day… if they indulge in corruption, we will take action

-Bihar Deputy CM and mining minister Vijay Kumar Sinha

Ironically, the sand smuggling continues rampantly even though most of the alleged kingpins, including several politicians, are either in jail or facing corruption charges from the Enforcement Directorate (ED) for money laundering.

Now the nature of the mafia itself has shifted. Gone are the brazen bosses with gold chains, rings on every finger, and black SUVs. Instead, villages like Bhagwan Bigha have become the new face of the mafia. There’s no kingpin. But the buzz and the network thrive. It has a life of its own.

“The illegal system is more systematic than the government’s. It seems impossible to go back to what it was,” said Kaushalendra Singh, a 43-year-old businessman from Aurangabad district.

The riverbeds have become hotbeds of crime and impunity where even the police fear to tread. Those who attempt to intercept trucks risk their lives. In May and June 2024, three policemen were killed in separate incidents tied to illegal sand mining. In some villages, tensions are escalating into gang wars between upper-caste mining groups and the Dalit communities they target for their sand-rich land.

But in most illegal mining hubs, everyone is complicit.

“You can’t pick fights with anyone because everyone has a stake in the sand,” said 50-year-old Radhe Shyam Yadav who lives near Bhagwan Bhiga.

Where baloo and booze meet

Often, the two rural mafias, sand and liquor, overlap. Literally under the top layer of the sand on the riverbank—a place for both digging and fermenting. These parallel stealth operations work in tandem, both holding up the night skies in Bihar’s villages.

Both pose different conundrums to the state’s politicians. In the sand mafia, politicians are embedded so deep that the state is bleeding revenue. As for alcohol, they still do not know how to honourably extricate themselves from the liquor ban and save face.

The white kurta-pajama mafia created by [the 2013 sand mining policy] continued to thrive. They have muscle power, weapons, and political backing

-Ramadhar Singh, four-time BJP MLA from Aurangabad constituency

For many young people, meanwhile, both trades offer better opportunities than run-of-the-mill jobs. The risks are high, but so are the rewards.

JP, a man in his 30s from Bhagwan Bigha, turned to sand mining and liquor production after struggling with low-paying jobs. He had once aspired to join the defence forces but the dream ended in 2015 when he failed the physical examination.

“For the next few years, I did odd jobs in the private sector, earning around Rs 8,000-10,000 a month, like delivering packages for an NGO during floods,” he told The Print on condition of anonymity.

About six months ago, he joined the baloo mining trade as a location informer. Soon after, he began producing desi liquor as well. He now earns around Rs 300 a day from sand and Rs 1,200 from liquor—nearly four times his previous income.

However, there’s always a looming risk. Competitors or irate customers could tip off the police. Or he could be caught red-handed while escorting an illegal tractor and have his bike seized.

Then there’s the social stigma of liquor production, unlike sand mining, where those who profit are envied, not judged.

“Sand trafficking is risky in terms of financial burden, and liquor manufacturing or smuggling can be three times more painful,” he said. “Firstly, it is a vice in society’s eyes. Secondly, you could spend years in jail. And thirdly, your family will suffer financially to get you out. My mother doesn’t even know that I am engaged in liquor.”

Among the dozen people in Bhagwan Bigha working part-time in both trades, he is the newest recruit. Villages near the rivers often combine sand mining with liquor production, while those farther away focus on hooch.

Producing desi liquor is labour-intensive. A single batch requires 10 kg of sugar and 500 grams of mahua flowers. Cheaper varieties use thethar, a type of wild grass that grows near canals. The mixture is buried under the sand in the Sone River for a week to ferment, then carefully extracted using steel pans.

Despite the skill and precision required, there’s no formal training. Most people learn on the job. Once some liquor is collected, it is tested by setting it on fire.

“If it burns, it is good quality,” said JP, speaking with a brisk expertise. “One batch is sold for Rs 2,500. We make 125 pouches out of it, each with 80-90 ml of liquor.”

He sells these pouches to middlemen for Rs 15 each, who then resell them for Rs 35-40, often right at customers’ doorsteps.

Then there are seasonal customer expectations to deal with.

“People will drink even the lowest quality in summer, but in winter, desi liquor has to be thick,” he said.

The past few weeks have been tough. On 1 January, he toiled to produce four pots to meet demand, but three turned out bad and had to be discarded. Plus, just before the New Year, police raided the area with the help of drones.

“Daaru ke chakker mein baloo bhi pakda gaya” (They came for liquor, but sand miners got caught too), he said.

Raids are financially crippling. A seized tractor wipes out nearly a year’s earnings for sand miners. For liquor producers, the damage is slightly lower—most use stolen bikes bought from the black market for Rs 5,000 to 6,000.

A new crop of middlemen has emerged—delivery workers who buy liquor from producers and resell it, often delivering directly to homes in the evenings.

Also Read: Red-eyed, lost young men in Bihar’s Seemanchal show how Nitish Kumar’s alcohol ban backfired

The rise of the Bihar sand mafia

The sands of the Sone River didn’t always harbour a sprawling underworld. In the mid-2000s, sand mining in Bihar was a modest, manual trade. Labourers dug with shovels, ferried sand on boats, and the sight of heavy machinery like JCBs or Poclains was rare. A tractor-load of sand cost just Rs 50.

Back then, villagers were not involved in the commercial sale of the sand. It was only local businessmen who obtained contracts from the government to extract sand to sell it.

Kaushalendra Singh, a young businessman from a zamindar family in Daudnagar, was part of this earlier era. He and five others pooled Rs 12 lakh as a security deposit to lease sand ghats near their town, located 35 kilometres from Aurangabad. Over the years, as construction boomed, their investment paid off. By the third term, their deposit had risen to Rs 72 lakh, and they planned for a fourth term.

Then came the Bihar Sand Mining Policy of 2013.

“The policy pushed out small businessmen like myself,” Singh said. Instead of leasing individual ghats, the government began auctioning all the sand ghats in entire districts as a single unit.

Even 15-year-olds are making liquor. Both baloo and daaru policies have turned out to be disastrous for the state

-Jai Prakash Singh, Bhagwan Bigha resident

“Now the deals were in the millions. Lakhpatis were out and crorepatis were in,” Singh said, alleging that the policy was designed to boost the political economy.

“Whoever got the bid would naturally bribe the minister or the secretary to secure an entire district for sand mining.”

Under the new policy, the government established 25 river units across 29 districts. In some cases, such as Rohtas and Aurangabad, the entire river stretch was treated as a single unit.

“This led to the rise of monopolies and gave birth to the sand mafia. Small-scale businessmen were crushed. They were either pushed out of the market or absorbed by the mafia on a monthly pay scale basis,” Singh said. He has since left the trade and now works as a property dealer.

A businessman familiar with Bihar’s political landscape said the main intention behind the 2013 policy was to enable a new crop of businessmen to flourish. But the conditions opened the door for coal mafias from Jharkhand’s Dhanbad to shift their attention to sand. Businessmen with political connections— like Surendra Kumar Jindal, Jagnarayan Singh, and Punj Singh — rushed into the sand mining industry. Today, all three face money laundering charges from the ED.

“These outsiders didn’t have competitors from within the state,” Kaushalendra Singh said. “Those from the state joined hands. It’s now a syndicate.”

Bihar’s sand trade bigwigs have faced intense heat since 2023, with the Enforcement Directorate swooping down on dozens of top players, most of them with political links, especially to the RJD.

Yesterday’s businessmen, today’s mafias

Some of today’s mafias were once legitimate businessmen with legal sand mining contracts, pushed out of the legal framework by the 2013 policy. And those in the sand trade say even a new 2019 policy did not alter this status quo.

“You gave us contracts to dig sand and sell it. Now you’re calling us mafia? We paid the highest bid to get that sand stretch,” said a businessman currently facing corruption charges.

In the last decade, Bihar’s political alliances have shifted repeatedly, with Nitish Kumar’s JDU alternating partners between the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and BJP. And not only have ministerial boards changed, so have policies for industries like sand mining.

“When Nitish realised that the 2013 policy empowered the RJD and mostly Yadavs to take over the sand business, he changed the policy in 2019,” the businessman quoted above claimed.

The Bihar Sand Mining Policy 2019 policy divided districts into smaller units. Each river within a district was treated as a separate unit, allowing more contracts to be issued. Major rivers like the Sone, Kiul, Chanan, and Morhar were divided into multiple ghats based on topography, with limits set at two ghats or 200 hectares per bidder—whether an individual, company, partnership, or cooperative society.

But the change did little to disrupt the entrenched mafia.

“The white kurta-pajama mafia created by 2013 continued to thrive,” said Ramadhar Singh, a four-time BJP MLA from the Aurangabad constituency and former cooperative minister in the Bihar government. “They have muscle power, weapons, and political backing.”

He pointed to Uday Singh, a sand mining heavyweight from Daudnagar, who has been charged by the ED for corruption.

“Whoever takes the tender for a ghat anywhere in the district must get Uday Singh as a partner. He has amassed massive agricultural land near the river,” Ramadhar Singh alleged. “If Uday Singh is summoned to a police station, he will appear in broken slippers, but he is a man of millions of rupees.”

Police and administrative officials also play a crucial role in sustaining the trade. In 2021, for instance, 17 officials across four districts were suspended for allegedly aiding and abetting the sand mafia.

“It is a business that can’t be done without getting mining officials and police on your side. The major chunk of bribes goes to these two posts. Posting in baloo hotspots is a money-making post,” the MLA said.

The sand trade isn’t just lucrative, but a pathway into politics, according to him.

“They aren’t janpratinidhi (public representatives) but dhanpratinidhi (money representatives),” he said. “You can be an MLA or MLC with the money from baloo. (The mafia has been) mainstreamed in politics now.”

But over the past few years, law enforcement agencies have ramped up crackdowns on the upper echelons of these networks.

Big fish in the net

Bihar’s sand trade bigwigs have faced intense heat since 2023, with the Enforcement Directorate swooping down on dozens of top players, most of them with political links. At the centre of the multi-state investigation is a Rs 250-crore sand mining ‘scam’.

The probe began after the Bihar police filed complaints against two companies for illegally extracting and selling sand, resulting in massive losses to the state exchequer.

While politicians from various parties are under scrutiny, the opposition RJD has been hit hardest. Businessmen accuse the government of “politically motivated” targeting, and there’s growing speculation that the raids have prompted some politicians to switch sides.

The state is going to elections next year. If RJD’s political funding has to be hit badly, hit the sand business

-Political insider from Bihar

Though minister of mining and BJP leader Vijay Kumar Sinha told ThePrint that the “mafia is the target and not political parties”, scepticism remains.

Last year, the late BJP leader Sushil Kumar Modi claimed the sand and liquor mafias were acting as “washing machines” for black money tied to RJD leaders Lalu Prasad Yadav and Rabri Devi.

“The state is going to elections next year. If RJD’s political funding has to be hit badly, hit the sand business,” said a political insider who wished to remain anonymous.

At the heart of the Rs 250-crore scam is Subhash Prasad Yadav, an RJD politician from Gopalganj and close aide of Lalu Prasad Yadav. Alleged to control 60 per cent of Bihar’s illegal sand mining, Yadav was arrested last March and is now in Patna’s Beur Central Jail.

Yadav is linked to several companies involved in sand mining. He is a director of Broadson Commodities Pvt Ltd and Banshidhar Construction Pvt Ltd, while his wife, Lalita Devi, associated with Radha Raman Construction and Marketing Pvt Ltd—all accused of illegal mining activities. His business partner Radha Charan Seth, a former JDU MLC, was also arrested last year.

The ED’s investigation has ensnared several others tied to the sand trade and Subhash Yadav. Former RJD MLA Arun Yadav and Uday Singh—the brother of RJD MLA Bhim Singh Yadav—face corruption charges, while prominent businessmen such as Surinder Jindal, Baban Singh, Punj Singh, and Jeevan Kumar have been arrested.

In December, the ED raided Hulas Pandey, a businessman and prominent member of the Chirag Paswan-led Lok Janshakti Party (LJP).

ThePrint could not access the email addresses of Subhash Yadav, Radha Charan Seth, Jeevan Kumar, Arun Yadav, and Bhim Singh Yadav; calls and text messages to them were not answered.

Meanwhile, to stamp out illegal sand mining at the ground level, Bihar has ramped up surveillance and enforcement with a mix of technology, community involvement, and steep penalties.

CCTVs, Digital Yoddhas, Baloo Mitra Portal

In November, Deputy CM Vijay Kumar Sinha carried out a dramatic “helicopter raid” on sand ghats, resulting in the capture of 3,000 trucks. The state has also been establishing control and command centres in mining hotspots.

It’s a clear message to the public that the government is not burying its head in the sand.

अवैध खनन के खिलाफ हेलीकॉप्टर से छापेमारी 15 लाख सीएफटी बालू जब्त।#IllegalSandMining #Bihar #BiharNews #VijayKumarSinha pic.twitter.com/D4P22Lz57U

— Vijay Kumar Sinha (@VijayKrSinhaBih) November 25, 2024

“We have installed CCTVs to monitor activities 24 hours a day,” Sinha told ThePrint. Citizens can now report illegal mining or overloaded sand vehicles via dedicated WhatsApp numbers. For acting as informers, they’re rewarded with cash and the title of Digital Yoddhas—or Bihari Yoddhas. On 2 January, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, along with his two deputies, rewarded 24 such informers.

“For a truck, the prize money is Rs 10,000, and for a tractor, it’s Rs 5,000,” Sinha said, adding that Bihar is the first state to introduce such a system. The state has also introduced rewards for the raiding teams that seize vehicles.

The crackdown will gradually fade once the money is made. Every raid in the illegal market drives up the bribe prices

-Mining insider

Meanwhile, penalties for illegal activities have been hiked: a Rs 10-lakh fine for a truck and Rs 5 lakh for a tractor. GPS tracking devices are now installed on sand transport vehicles to prevent multiple trips within a single time slot.

“If they get stuck in traffic or meet with an accident, we will consider it, provided they submit pictures on the WhatsApp groups launched. However, if they indulge in corruption, we will take action,” Sinha added.

To make sand accessible to citizens, the government has launched the Baloo Mitra Portal, which sells sand at government rates. The government has also allowed local communities to commercially sell sand from their fields near riverbanks, provided they pay royalties and obtain prior permission.

According to the Bihar Mining Department, 152 of the state’s 369 auctioned sand mining ghats are currently operational. These are now geo-fenced to curb unauthorised activity.

But in the shadow economy of illegal mining, the state’s actions carry a different meaning. Insiders say raids are often interpreted as signals to raise bribes.

“The crackdown will gradually fade once the money is made. Every raid in the illegal market drives up the bribe prices,” an insider claimed.

Money, mobility, mayhem

Just a decade ago, about 80 per cent of Bhagwan Bigha’s residents relied on farming, while some worked in the CRPF, Bihar Police, or as teachers, say residents. Everything started to change when the 2013 sand mining policy was enforced.

“Suddenly, JCBs, Poclains, and multi-axle trucks lined up at the river. People called back their sons who were studying in other states,” said 27-year-old Rajnish Yadav, one of only two village residents to land a government teaching job in the past decade. Apart from their families, the rest of the village is now involved in sand mining.

Rajnish spoke of a friend with a BTech degree who scraped by on a Rs 20,000 monthly salary until he switched over to sand mining.

“Today, he earns over a lakh monthly,” Rajnish said. Once prohibition came into force in 2016, yet another demand and avenue for work opened up.

Some make money from sand, some from liquor, and a dozen or so dabble in both, he added. Farming has become an afterthought.

“Even 15-year-olds are making liquor. Both baloo and daaru policies have turned out to be disastrous for the state,” said 80-year-old resident Jai Prakash Singh.

Every three to six months, the village is rocked by police raids, with drones hovering over the river and clashes between the sand mafia and administration. But then it’s quickly back to business.

“They destroy the liquor stills, seize illegal sand, and issue challans for vehicles. But by the time they reach the police stations, the bricks of the liquor pots are already being put back,” Jai Prakash Singh said.

A 500-metre stretch along the banks of the Sone River is where most of the action unfolds. JCBs and Poclains dig relentlessly all day, stretching as far as the eye can see. The mining rules mandate that sand should not be mined deeper than 3 feet to prevent excessive extraction, but here, no such restrictions apply. The Sone River now resembles a highway riddled with potholes.

Farmers along major highways have leased their agricultural land to sand mafias. These plots are used as dumping grounds to store baloo for the monsoon months of July, August, and September, when sand digging is prohibited.

When the big names are jailed, the trade doesn’t stop—it simply shifts to their deputies and their vast network of associates.

In Daudnagar, for instance, Munna Sharma is now said to call the shots. A decade ago, he was a Tata Maxi driver ferrying passengers between Aurangabad and Daudnagar. Today, he oversees four sand ghats: Tejpura, Nanhu Bigha, Barun Keshav, and Kera.

“Ever since he got into the sand business, he has become a millionaire,” said Chintu Mishra, a resident in his 40s.

Also Read: Sand miners are the new narcos. Rajasthan gangs offer cash, career, swag

Bihar’s mini booze barons

For Kiran Devi, a 40-year-old Dalit woman in Bhagwan Bigha, sand mining isn’t the problem. Her husband earns Rs 500-700 a day loading trucks for the miners. But liquor is.

“The government did the right thing to ban this poison. It is far more of a sin than loading sand onto the tractors,” she said, as a group of her friends murmured in agreement.

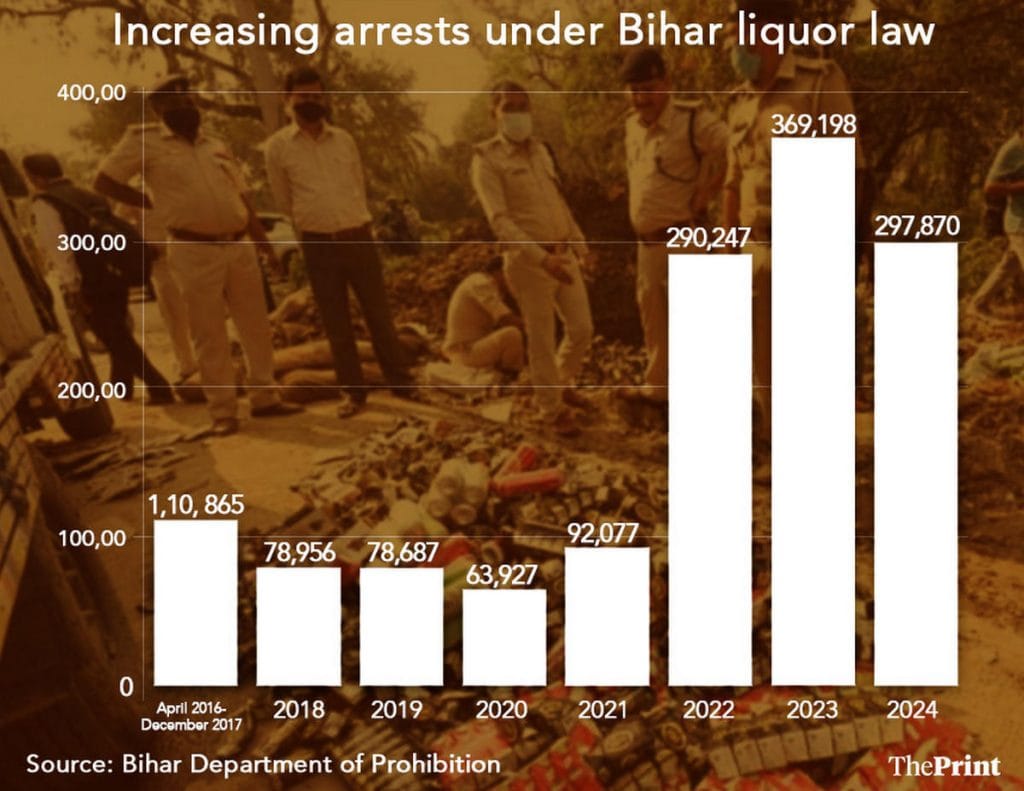

Since 2016, nearly 14 lakh arrests have been made under Bihar’s liquor law. And according to BIPFP’s Dr Bakshi Amit Kumar Sinha, the ban has shown positive signs, including less domestic violence and fewer impulsive crimes.

“People are spending less on medicine, which means they are falling sick less often. Dairy shops have replaced liquor shops, and kuccha houses have been transformed into cemented houses. All these factors contribute to the state’s economy,” he said.

Yet prohibition in Bihar hasn’t erased alcohol; it’s only driven it underground, complete with a network of manufacturers and stealthy delivery agents.

“Liquor is delivered by three bikes. The first and last bikes escort the middle one, which carries the liquor. In case of a raid, one can always abandon and leave,” JP said.

It helps, he added, that lower-ranking policemen and home guards are often among the clientele.

“They will ask for it for free or sometimes pay a bare minimum price,” he sighed.

The customer base for desi liquor has expanded over the years. Teachers and government employees no longer look down on it, according to JP. Rickshaw pullers, competitive exam aspirants, and even school kids deliver liquor part-time for extra cash.

Still, the money doesn’t translate to flashy lifestyles like in Rajasthan’s mining areas, where a black SUV and the latest iPhone are status symbols. Here, it’s mostly spent on lottery, gambling, and more liquor, claims JP.

“Galat cheez ka paisa galat mein chala jata hai, sirf samajhdar log hi sahi se kharch karte hain” (Money earned through wrong means is spent on wrong things; only wise people spend it properly),” he said.

There are exceptions, however.

KK, 22, came to Patna from Jharkhand to prepare for government exams. Instead, he became a liquor entrepreneur, delivering to the city’s elites. With his family’s small hotel closing and money troubles, he started as a daily wage delivery agent after the second wave of COVID-19.

“The dealer paid me Rs 100 per day—at 11 pm after I had done my last delivery,” recalled KK, who could pass for a studious university student with his long hair and glasses.

Then, his uncle encouraged him to start his own operation and he took the plunge. Even an illegal venture needed capital, and KK had none, but he began by borrowing and reinvesting his profits.

“The profit was 50 times higher than what I made daily for delivering,” he said. Within six months, he had enough to expand into a full-fledged business. Today, he employs six young men, aged 15-21, to deliver liquor to middle-class and elite homes in Patna.

“The monthly turnover is Rs 25 lakh, with profits of around Rs 4-5 lakh,” KK told ThePrint.

Staying ahead of the competition is a challenge, though.

“Every street has 5-6 people delivering liquor, sometimes for Rs 50 less,” KK said. “There are even husband-and-wife teams doing this.”

The most in-demand brands are 8 PM, Blenders Pride, Black Label, and Royal Stag.

“We talk in codes such as BP for Bade Papa, 8 PM is called Fruity Pack, and RS is Rocky Singh,” KK added.

He is not worried about the police. He claims they can be “bribed easily” and that those who are languishing in jails are mostly poor people who can’t grease palms.

His real fear is that his mother will find out what he does for a living.

“Liquor brings shame. God forbid, my mother comes to know what I do. I don’t know how I will face her wrath,” said KK, who plans to turn his black money into a white-collar business by 2027. “She still believes I work in the solar panel industry.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Excellent reportage. Kudos to Ms. Jyoti Yadav. Keep up the good work.

Bihar is indeed a cesspool. Always at the bottom across all HDI parameters. No wonder Biharis migrate to other cities and never come back.

The sad part is that once in a different state, say Delhi, they try their utmost to disown their Bihari identity. Most would not say that they hail from Bihar – such is the stigma associated with the state and it’s people.

Thanks to AASU and other such active organisations, Biharis are not really welcome in Assam. Otherwise, even Guwahati would have turned into a mini-Delhi.

I don’t think CM Nitish Kumar thinks any longer in such grandiloquent terms as creating a legacy. Author of the Prohibition policy, which he thought would create a national women’s constituency for his prime ministerial ambitions. Now down to ensuring that jab tak samose mein aaloo hai, he remains in the saddle.