Nagaur/Sawai Madhopur: A little before midnight, dozens of SUVs, campers, and dumper trucks chased each other for 90 minutes at close range on National Highway 485 in Rajasthan’s Nagaur district in August. The convoy crossed seven villages across 25 kilometres. There was firing and stone pelting. It was a mafia war of another kind. At stake were two trucks filled with something precious and central to India’s growth story. Sand dug illegally from rivers.

Bloodshed is part of the game. In the high-octane chase that summer night, a dumper deliberately mowed down 29-year-old Rajuram Jat near Sanjoo town. He died instantly. He had gone out in the night to support his cousin in a gang war over sand. Three village gangs — curiously named 0044, 4700 and BMC — have been locked in a battle for the past six years for monopoly over sand from the nearby Luni River.

India’s unprecedented infrastructure boom of the past two decades has birthed a new kind of rural and small-town criminality called the sand mafia. And it wraps businesses, politicians, and ganglords in a tightly interlocked rapacious spiral that has resulted in violent attacks, murders, and ruining of rivers in many Indian states. And the Chicago-style omerta among the sand beneficiaries in Rajasthan is ironclad.

In rural areas, illegal sand mining is the hottest new cash-rich job for the youth. The career path is well laid out — from starting off as drivers to becoming gang lords.

And all this is happening under the government’s watch.

“The government has two cash cows — liquor and sand. Legal or illegal, the government loves them both ways,” said Jitender Kumar Sharma, a construction builder based in Jaipur. “Criminality is a byproduct of sand mining.”

But profitability is the great leveller. Today, riverfront land commands a higher price than even prime highway real estate.

Luni, Banas, and Katli rivers are seasonal, flowing only during the monsoons. But deep pits due to sand mining now prevent water from flowing even during this season.

Also Read: UP is the new liquor capital—Record revenues, home bars, model shops. Yogi govt loving it

Blood money, politics, caste

Grocery store owner Rajuram’s murder sent shockwaves through the region, bringing mining operations to a screeching halt for two days. The Luni River was strangely silent. The tractors, trucks, and JCBs stood idle outside dhabas and petrol pumps. The sand lords from rival gangs all went on the run.

But in just 48 hours, their foot soldiers brazenly returned with JCB excavators, shifting their operations to spots with a lighter police presence.

Then, about a month later, local newspapers reported the Nagaur police’s breakthrough in the “Rajuram hatyakand”, with the arrest of Ranesh Kamedia, a member of the BMC gang.

“Ranesh, the main accused of the murder, was hiding in granite factories in Hyderabad, Bengaluru, and Tamil Nadu. The police searched 150-200 granite factories, examined CCTV footage, and conducted toll booth checks to nab him,” read a 17 September police note, written in Hindi, that was sent to media houses.

However, what did not make it to the headlines has now captured the imagination of the entire hotbed — the details of the gang war and the hectic negotiations for ‘compensation’.

Hushed meetings and bargaining have been underway between the sand mafia, local politicians, panchayats, and Rajuram’s family for nearly two months in his village Dangawas in Merta tehsil.

Everybody is involved, but nobody is aggressively seeking legal justice. Instead, the focal point is a demand for compensation, rumoured to be around Rs 1 crore.

“We are hurt by what had happened. But we are compromising for those who are left behind — his wife and two children,” said Rajuram’s cousin Sunil Jat, who was with him on the night that the gang war erupted.

Sunil was booked by the police in a counter FIR and was out on bail the day ThePrint met him.

What complicates matters is that caste and politics are closely intertwined with the gang wars.

The sand crime lords— big and small— coopt local politicians and become local bahubalis during election campaigns. Word spreads fast about their influence-mongering and silences others into compliance.

Sand mafia ‘success stories’ like 4700’s Manish Somarwala and BMC’s Ranesh move around with Bollywood swagger and shows of strength. They are role models for many village youth.

Ranesh Kamedia — who goes as Ranesh Rana Choudhary on his social media— is a prime example of this.

A dimple-cheeked and dapper 28-year-old, Ranesh calls himself a “political leader” on Instagram. His account is filled with selfies with Nagaur MP Hanuman Beniwal, a leader of the Rashtriya Loktantrik Party (RLP) with a large Jat following.

“Ranesh is close to MP Hanuman Beniwal and we are not. Ranesh supports his election campaign,” Sunil claimed.

Earlier this year, when MP Beniwal held a Jan Akrosh rally, a row of JCBs showered flowers on him, one of which belonged to Ranesh, claimed Prem Singh Shekhawat, a Nagaur-based reporter. Ranesh also featured prominently on billboards in Nagaur advertising Beniwal’s rally.

While Beniwal has given thunderous speeches against the “bajri (sand) mafia”, most of his rhetoric is directed at mining baron Meghraj Singh ‘Royal’, a legal operator from the Rajput community.

“Ranesh and his gang are behind the protests that Beniwal is staging against Meghraj Singh,” Sunil alleged.

Beniwal, however, argued that his objective was to end Meghraj Singh’s “monopoly” over river sand.

“Meghraj has captured the entire sand business in Rajasthan. He is the real mafia, not the youth who operate on a small scale. After I filed five-seven FIRs against his illegal activities, he has packed his bags from Nagaur. But there is still a sand stock, which again is also illegal,” Beniwal said.

If the RLP wins enough seats in the upcoming Rajasthan assembly elections, the party will push to democratise sand mining, he added. The RLP is contesting around 100 out of the 200 assembly seats in the state.

“If I get 80 seats, I will make sure that the government brings in a policy to grant small leases of few hectares. This is the way to engage aam log (ordinary people) in the mining business and it will also stop illegal mining,” he said.

Beniwal refuted allegations that he was close to Ranesh Kamedia. “The JCBs in my rally did not have sand mafia written on them. As for Ranesh, anyone can get a photo with me. It doesn’t necessarily mean that I am supporting them,” he said.

Chasing the high life

Sand brings quick easy money for the village youth. Countless school and college dropouts are jumping into this line — their career role models are 4700’s Manish Somarwala and BMC’s Ranesh. These ‘success stories’ move around with Bollywood swagger and shows of strength — fancy cars, groupies, and nights out on the town at fancy restaurants. The dirty money is bursting at the seams.

There is a hierarchy, but aspirants can move up the ladder quickly.

Teenagers often start off as JCB drivers or as escorts leading the way for sand-filled tractors and trucks through highways and kutcha roads. Escorts have to stay on high alert and warn gang members if they catch a whiff of a possible raid. The risky job pays only Rs 10,000-15,000 per month, but there’s a good growth path for those who have staying power.

High-performers eventually receive a stake in the business — starting with 5 percent and growing over time — and many invest in their own dumpers or tractors. But it usually takes about five years to finally become a Ranesh whose job it is to manage gang rivals, provide muscle and money power during elections, and grow the sand business.

Ranesh, a criminal from Danagwas village in Nagaur, used to run a liquor store but became an illegal sand mining entrepreneur around 2017.

Today, his career trajectory is the talk of the town—he employs over 30 people, his birthday bashes are the biggest in the village, and the MP seemingly hobnobs with him.

Ranesh is seen as a challenger to the legal mining heavyweight Meghraj Singh and a mentor for young boys. One of his Insta posts, set to a DJ remix, shows him teaching a teen how to drive a JCB. “Add new mamber (sic),” the caption says.

Another ‘achiever’ is 27-year-old Mahendra Anwala, 27, of Nagaur’s Jhinitiya village.

He learnt the ropes as an escort for illegal sand miners, watching out for the cops at chaurahas and keeping tabs on the chatter at mining offices, according to his associates.

After about five months on this job, Anwala started renting a JCB for Rs 3,000 per day to mine sand.

“Each day, he’d fill 50 tractors and earned at least Rs 4 lakh in profits every month,” claimed an admiring associate on condition of anonymity.

A few years ago, he, along with his uncle Bhiyaram and partner Chenaram, formed the BMC gang. They’ve since shifted from leasing land to owning it and now possess a Poclain excavator, two JCBs, and three dump trucks. They cruise in black Scorpios, the badge of honour for illegal miners. Ranesh has also emerged as a power centre in their gang.

Sand is the new narcotics. Except there is no jail for stealing or smuggling the sand.

-Jaipur-based mining official

Everyone wants in on the action. Over the last decade, many families have sold their wheat and bajra fields and turned to sand mining. Others have profited from selling riverbed land, and investing in agricultural or residential plots elsewhere.

Signs of success include owning the latest iPhones and acquiring a new black SUV each year. Weddings are a chance to lay it all out, with flashy celebrations that aim to mirror big-city glitz.

But the ultimate status symbols are JCBs and dumpers. The owners take them for spins, performing stunts and blaring loud Rajasthani DJ songs.

“Sand is the new narcotics,” said a Jaipur-based mining officer. “Except there is no jail for stealing or smuggling the sand.”

The gangs of Nagaur

The illicit sand trade flourishes wherever there are rivers, but some areas are more notorious than others.

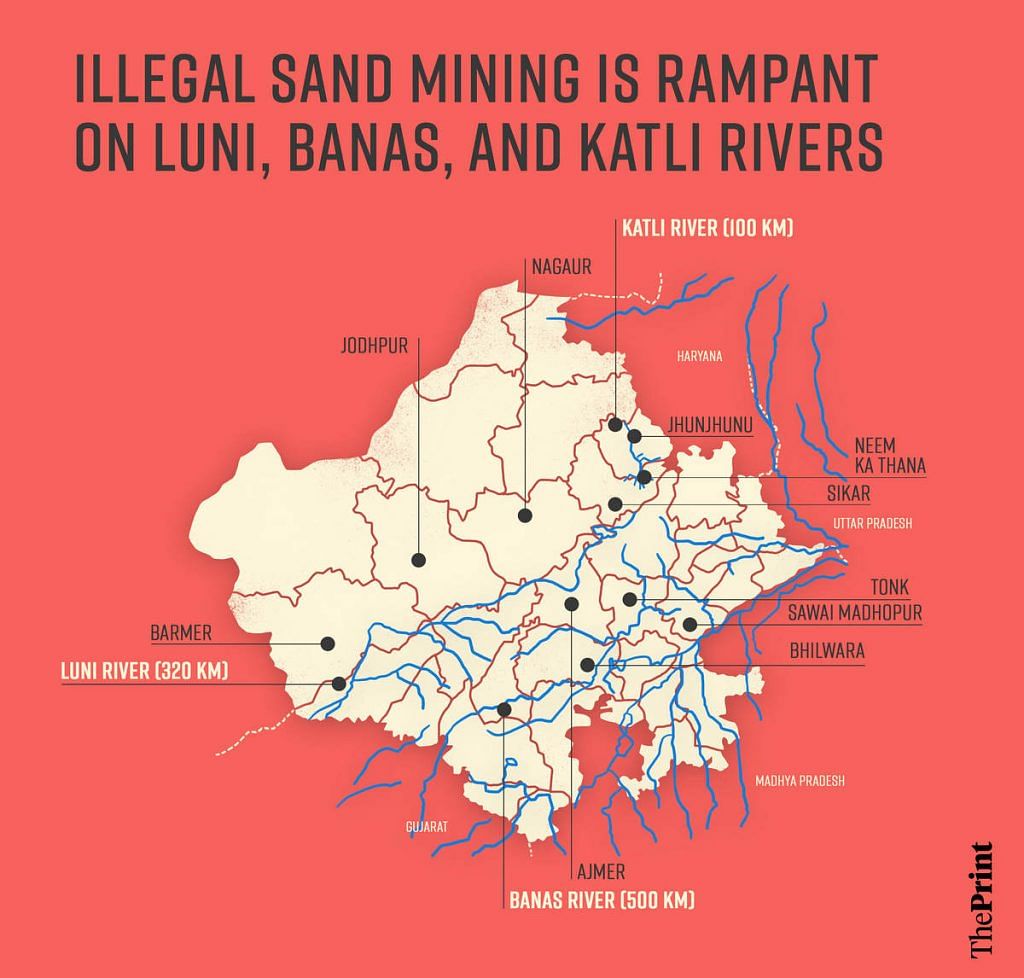

The 320-km Luni River cuts through central Rajasthan, including Ajmer, Jodhpur, Barmer, and Nagaur. Farther east, illegal activities have flourished along the banks of the 500-km Banas River, especially in Sawai Madhopur, Bhilwara, and Tonk. Similarly, the 100-km Katli River serves Sikar, Jhunjhunu, and Neem Ka Thana districts, but the latter is the biggest mining hotspot.

All three rivers — Luni, Banas, and Katli — are seasonal, flowing only in the monsoon season. But deep pits resulting from sand mining now prevent them from flowing even during the monsoon.

Illegal sand mining is entrenched in all these regions, but the business models vary.

In eastern Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur, for instance, it’s more like a cottage industry where everyone shares in a slice of the pie. Thousands of villagers, mostly from the Gurjar and Meena communities, have bought JCBs, trucks, and tractors through EMI schemes and every second person is a mini-sand baron.

However, on banks of the Luni, a clutch of organised gangs fight for monopoly, especially in the Jat-dominated Riyan Badi and Merta tehsils of the Nagaur district.

The intense rivalry among the top three gangs in the region ignited the bloody chase in August.

On one side was the Bhiyaram-Mahendra-Chenaram (BMC) gang, named after its founders. On the other were the 0044 and 4700 gangs, named after JCB number plates. All gang members flaunt the same plate number to assert their affiliation.

(Mafia leaders) started as labourers and drivers for legal mining firms until they learnt the ABCD of the game themselves. The river belongs to all and so does the sand

-Jitender Kumar Sharma, Jaipur-based builder.

The Nagaur police filed two FIRs in the case against 24 men. The first FIR was filed by Rajuram’s cousin who was supporting the 0044 gang and the counter FIR by the 4700 and BMC gangs.

BMC operates out of Jhitiyan village in Merta tehsil, where the three founders and top operatives like Ranesh Kamedia rule the roost. Nearby Rohisa is home to gang 4700, where Rampal Somarwala, Manish Somarwala, and Ramchandra Somarwal are the head honchos. Dangawas, situated more than 20 km from the Luni River, is the headquarters of gang 0044, where the main players include Manish Kamedia and Shyam alias Sam.

These rival gangs are often at each other’s throats, but they do find a sense of brotherhood when they face common challenges like police crackdowns, uncooperative legal leaseholders, and resistance from activists and journalists.

The leaders of these gangs, including Ranesh, Mahendra, Ramchandra, and Manish, are among the ‘most wanted’ men in Nagaur, with bounties of Rs 25,000 on their heads. Most of them have at least four to five cases against them in multiple police stations under various IPC sections related to offences like rioting, disorderly conduct, public mischief, and criminal conspiracy.

But they weren’t always criminals. Ranes, 28, ran a liquor shop. Mahendra and Ramchandra were farmers. Suresh and Manish completed their schooling up to Class 12 before entering their life of crime.

“They started as labourers and drivers at legal mining businessmen’s firms until they learnt the ABCD of the game themselves. The river belongs to all and so does the sand. Then they started digging the river with their own tractors and JCBs,” said Jitender Kumar Sharma, a Jaipur-based builder.

The Supreme Court’s 2017 mining ban had an unintended consequence: it halted legal mining operations while providing an opportunity for the illegal ecosystem to thrive.

How a blanket ban unleashed the mafia

A little more than a decade ago, the residents of Jhitiyan and Rohisa lived simple lives, tending to their crops and cattle. The sand along the Luni River did not scream riches to them.

“Whenever someone needed bajri (sand) for construction, they would get it for free from the river after paying some royalty to the government. And that’s all,” recalled Naveen Sharma, president of the All Rajasthan Bajri Truck Operators Welfare Society (ARBTOWS), which represents the interests of sand transporters.

Things started changing in 2012 when the Supreme Court stepped in to protect rivers and curb unchecked mining. The court ruled in Deepak Kumar vs Government of Haryana that leases for sand mining could only be granted after environmental clearance (EC) from the central government. The court also restricted the depth of river sand mining to 3 metres.

This ruling, though intended for environmental protection, served the interests of other stakeholders too. Mining magnates wanted big leases to create a monopoly and state governments saw an opportunity to generate revenue through regulation.

It changed the way business operators and states dealt with sand mining.

One of the beneficiaries was Meghraj Singh, a former chef at Jaipur’s five-star Rambagh Palace Hotel who later ventured into the liquor and mining businesses, earning the title of “sand king” in Rajasthan.

In 2013, the Rajasthan government auctioned five-year mining rights, issuing 82 leases and earning nearly Rs 500 crore in revenue. Sixty percent of these leases went to Meghraj Singh’s MRS Group of Companies, including for the Nagaur stretch of the Luni River.

Meghraj has captured the entire sand business in Rajasthan. He is the real mafia, not the youth who operate on a small scale

-Hanuman Beniwal, Nagaur MP

Singh told ThePrint that he spent crores on constructing checkposts and buildings and hiring drivers, labourers, and managers in the area.

But in 2017, a big blow came for him and other lease-holders like Aman Sethi, Ashok Chandak, Manjeet Chawla, and Rahul Panwar.

The Supreme Court imposed a blanket ban on sand mining in the state until a scientific study on replenishment was conducted and environmental clearances were issued from the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change.

The court also ordered the chief secretary to file an affidavit on allegations that the Rajasthan government colluded with miners to allow unchecked sand mining.

Singh said that the worst phase of his 25-year-old mining career was in 2017.

“When we were given leases in 2013, the environmental clearances were kept pending with the ministry for years. The EC had been reduced to a piece of paper and a tool for extortion money from businessmen who wanted to do legal mining. The court allowed us to work on temporary permits (before 2017),” he explained.

The ban, meanwhile, had an unintended consequence. The thirst for construction sand never waned, and a throng of eager suppliers emerged.

The drivers, labourers, and managers who worked with Meghraj Singh and other legal operators became thekedars (contractors) themselves. They were the new sand lords of the villages and no rules applied to them.

“It shattered our confidence,” Meghraj said.

However, members of the sand mafia allege that the mining lease-holders colluded with them for a cut of the profits.

“They had the resources, and the villagers had the muscle power. There was no other way but to join hands,” said a small-scale illegal sand miner on condition of anonymity.

The new breed of miners fixed commissions for the station house officer (SHO), regional transport officer (RTO), mining officer, and representatives of local bodies. Local politicians propped up the enterprise from the shadows, providing the villagers, constructors, and drivers immunity and political patronage.

The writing on the wall is clear: this is the mafia’s territory. And nearly everyone else has been sucked into this dangerous game too.

A new turf war

In 2021, the Supreme Court lifted its ban on riverbed sand mining. It acknowledged that the ban had inadvertently led to an explosion of illegal mining and related crimes.

But when legal players like Meghraj Singh resumed their businesses, the illegal operators refused to back down.

Last year, Singh, armed with an environmental clearance, ventured back to the Luni River, ready to resume mining without reliance on the sand mafias.

“He didn’t need the sand mafias any longer to help him from the Luni river,” said a former employee who worked at Meghraj’s sand stock unit in Nagaur.

The EC (environmental clearance) had been reduced to a piece of paper and a tool for extortion money from businessmen who wanted to do legal mining

-Meghraj Singh, legal mining baron

But the Nagaur ganglords were unyielding, unwilling to relinquish the territory they had seized for themselves. They launched a fierce war.

Hundreds of vehicles belonging to Meghraj were burnt down. Check posts were destroyed and his men were chased out by the gangs. Mafia members at times recorded videos of these incidents and then shared them triumphantly on WhatsApp and social media, complete with thumping soundtracks.

Meghraj found himself unable to exercise his rights on his own legal lease, as the mafias were now encroaching even upon legitimate territories.

A complaint was filed at Merta police station on behalf of Meghraj. Ranesh was the main accused this time too.

Police records indicate that the case remains pending, but Meghraj Singh is swiftly disengaging from Nagaur. He’s completed his permit’s remaining duration and relinquished the lease.

People started spending crores to get elected as sarpanch. It gets them a monthly commission in lakhs of rupees

-Kailash Meena, activist

Singh’s associates in Nagaur as well as Jaipur claimed that he has already sold a building and checkpost in the area and is wrapping up operations. He still has stock near the Luni river, which he must sell within the next six months.

The writing on the wall is clear: this is the mafia’s territory. And nearly everyone else has been sucked into this dangerous game too.

A parallel economy

In the mining hotspots, everybody is complicit. And everyone makes money— from young drivers to the old men discreetly stationed at tea stalls, panchayat bhawans, or chaurahas, to keep an eye on law enforcement.

Others profit indirectly. In some villages, residents set up makeshift ‘tax’ booths with official-sounding names like village development tax, temple tax, and gaushala tax. At night, they issue “tax permits” to trucks and tractors passing through their village on the way to the highway.

“Usually, if we have to cross 7 to 8 villages, then we end up paying between Rs 1,000-1,500 for each round,” said a truck driver who delivers sand from Luni to Sikar.

If a driver refuses to pay, villagers “tip off” the police about illegal sand mining.

“Once we get caught, we will have to pay a penalty of Rs 5 lakh for a truck to get it released. Then the RTO, mining office, and the local court get involved. It is a costly affair then,” the driver added.

It is no longer just a financial lottery. The illegal mining nexus allegedly influences the panchayat elections too.

“People started spending crores to get elected as sarpanch. It gets them a monthly commission in lakhs of rupees,” alleged Kailash Meena, an anti-sand mining activist from Neem ka Thana.

The pervasive murk of illegal sand mining has led to widespread crime and corruption in Rajasthan.

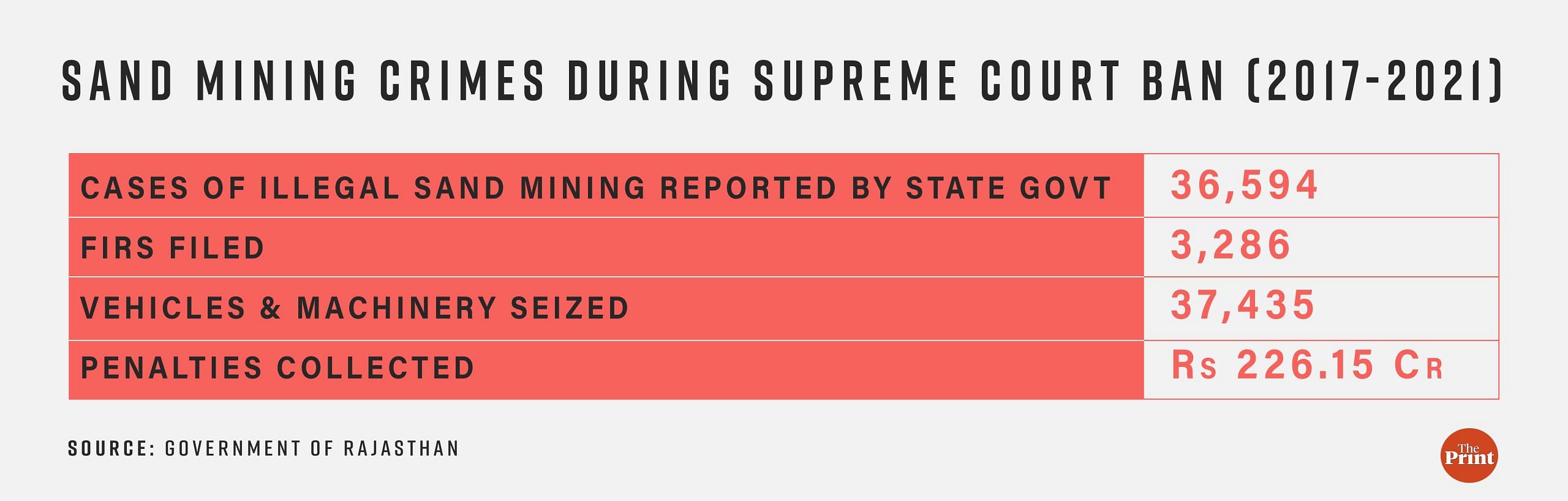

Rajasthan reported 36,594 cases of illegal sand mining between 2017 and 2021. The state filed 3,286 FIRs, seized 37,435 vehicles and machinery, and collected penalties of Rs 226.15 crore. Activists argue that many more cases went unnoticed or unreported.

A former director in the Rajasthan mining department suggested that the most workable solution would be to loosen restrictions on sand mining.

“Police and politics are hand in glove with the mafias. The mining department cannot tackle it because of its limited resources,” he said on the condition of anonymity.

However, many police officers in the mining areas refute the allegation that they collude with the mafia.

A station house officer who was earlier stationed at the Padu Kallan Police Station in Nagaur told ThePrint that mining did not directly come under the jurisdiction of law enforcement.

“Our role starts when there is a law and order situation due to illegal sand mining,” he said.

He emphasised that corrupt police personnel face disciplinary action.

“Last year, the entire Riyan Badi police chowki in Nagaur was suspended for their involvement in the illegal sand mining,” he said.

Also Read: A Tamil Nadu village and its precious soil put Chandrayaan-3 on moon. Now, farmers are scared

Khatedari system: a loot for all

In the last decade, India has built massive six-lane highways, new airports, medical colleges, subways, and skyscrapers in the metro cities. There is a greater demand for construction materials than ever.

“The third most consumed material after air and water in the world is sand,” said builder Jitender Kumar Sharma. “The consumption of sand is thrice that of cement in construction.”

Vikas (development) has destroyed the relationship between villages and rivers. Sand is the lungs of a river. The rivers can’t breathe as their lungs are stolen now.

Rajendra Singh, environmentalist & ‘water man of India’

When the ban on sand mining was in force, supply was facilitated by two factors— the rise of the mafia and the state government’s decision to allow sand excavation in khatedari lands.

In Rajasthan, khatedari refers to a system that allows landowners to sell, mortgage, or lease their government-given land, typically for farming.

However, in 2017, the state government amended the Rajasthan Minor Mineral Concession Rules, allowing short-term permissions known as ‘ravannas’ for sand mining on khatedari lands, specifically for government or government-supported projects. In 2019, 194 leases on khatedari land were granted.

This new system created a fertile ground for exploitation.

The sand mafia did not even touch the khatedari land but stole the entire river bed in many cases

-Kishor Kumawat, researcher & activist

The entire illegal ecosystem gravitated towards farmers with land adjacent to riverbeds, offering them prices up to five times the value of their agricultural plots.

The gangs wanted access to a permit and riverbeds. The landowners wanted a payday.

“It was a good deal for many. There was not any way to get much from these fields as they were dependent on rainwater. So, they sold the land,” said a resident of Nagaur’s Riyan Badi tehsil, asking not to be named. Others kept their land, but rented it to the gangs monthly.

Simultaneously, the sand mafia, using khatedari leases, dug pits, some as much as 100 metres deep, along riverbeds. They also exploited a single permit for multiple trips between the river and their drop-off points. For instance, a permit issued from Nagaur to Mathura might be employed for deliveries in Jaipur.

“The sand mafia did not even touch the khatedari land but stole the entire river bed in many cases,” said Kishor Kumawat, a Neem Ka Thana-based mining activist and researcher.

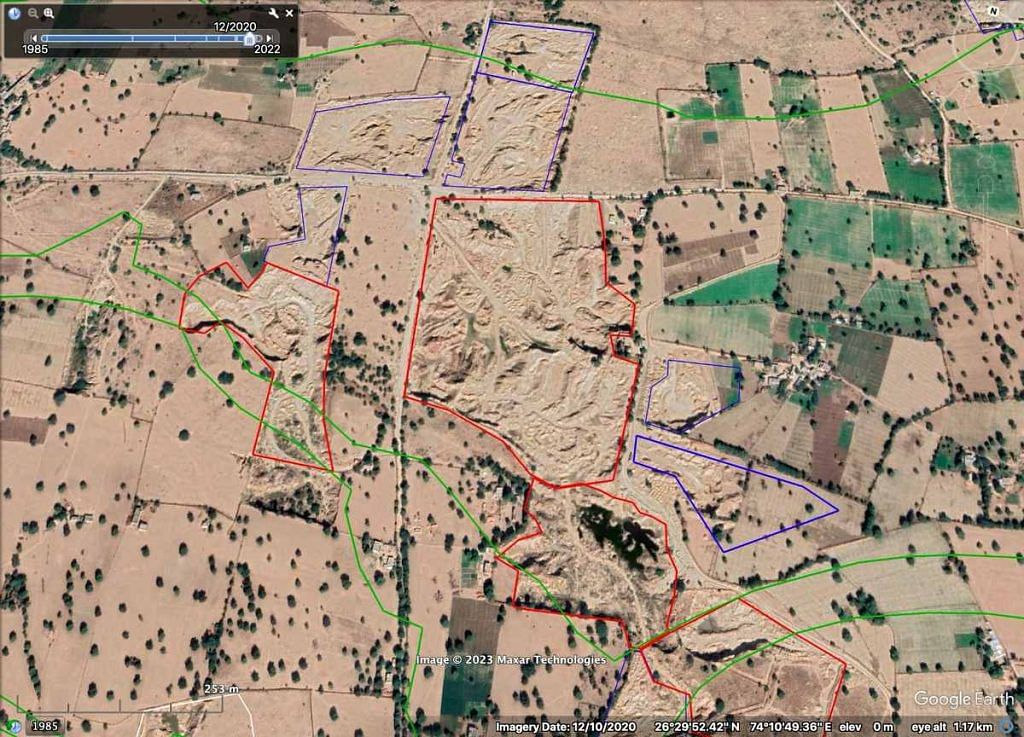

Kumawat, at considerable personal risk, filed numerous RTIs with the mining department to uncover extensive corruption in khatedari lands. He compiled comprehensive data, including satellite and drone images, to illustrate the spread of illegal mining across ecologically fragile river systems.

In 2020, the issue of khatedari lands reached the Supreme Court following a petition by Naveen Sharma, the president of ARBTOWS. The court appointed a Central Empowered Committee (CEC) to investigate, uncovering widespread corruption during its 2020 inspection.

“The team visited Bhilwara district along with the DM and the SP. We saw rivers being mined in the name of khatedari land,” said Naveen Sharma, who accompanied the CEC team during the inspection.

The CEC, in its December 2020 report, accused the state government of participating in the “free-for-all loot” of riverbed sand.

It highlighted that 194 khatedari leases for sand mining had been granted near riverbanks, likely to exploit their “locational advantage”. Moreover, the CEC noted that agricultural lands could not provide quality construction sand.

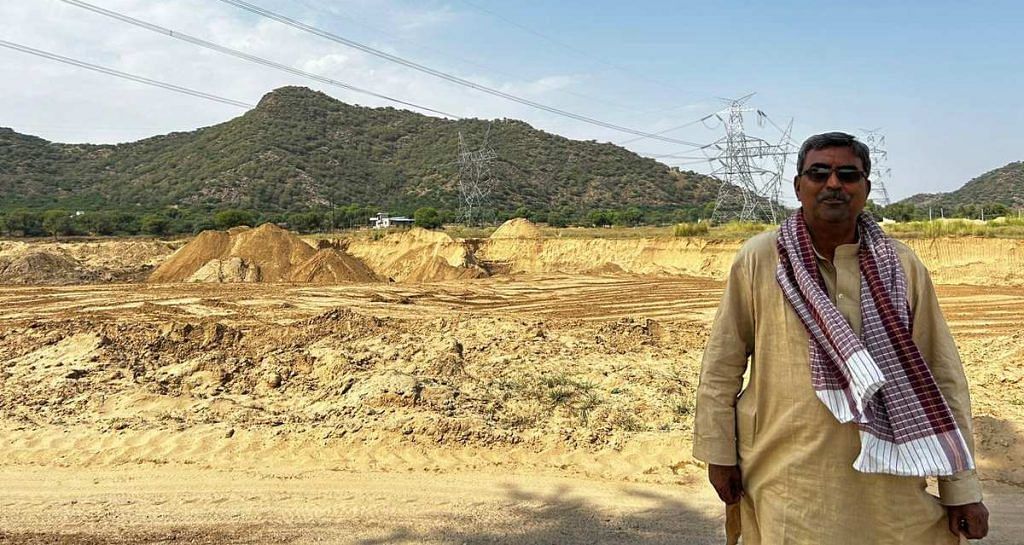

The CEC recommended the cancellation of khatedari leases within 5 km of riverbanks, but when ThePrint visited villages on the Banas and Luni banks in October, the frenzied digging appeared to continue unabated.

Murder, mayhem, and silence

In the cash-flush world of mining villages, dissent is rare, and for good reason. Those who dare to protest face peril.

Last June, alleged members of the sand mafia gave chase and attempted to assault a former sarpanch in retaliation for raising concerns about Luni River mining. In 2018, the sarpanch of Hathdoli village in Sawai Madhopur was beaten to death by a mob for joining a raid against sand miners.

The message was loud and clear. Everybody has their hand in the till. And activism is dying.

This issue is not confined to Rajasthan. Right to Information (RTI) activists, journalists, and officials alike have fallen prey to the sand mafia.

Data from the non-profit South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) shows that between April 2022 and February 2023, there were three deaths and five injuries from attacks by illegal miners on RTI activists and other adversaries in western Indian states, including Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, and Madhya Pradesh.

Journalists too have paid a heavy price, with casualties such as Sandeep Sharma, mowed down by a dumper in 2018, and Shubham Mani Tripathi, shot to death in June 2020, not long after he posted on Facebook that he feared reprisals because he investigated murky land deals linked to illegal sand mining.

In October 2022, Gujarat RTI activist Ramesh Balia and his son were run over by the SUV of an alleged illegal sand miner. The activist’s son died. This April, three officials of Bihar’s Mines and Geology Department, were violently attacked by the alleged sand mining mafia in Bihta town, with “hundreds” of residents joining in.

While measures like increasing road checkpoints and employing drones and satellite imagery to monitor illegal sand mining help to some extent, it’s a tough task when everyone is involved.

Also Read: ‘Let’s teach police a lesson’ — illegal miners who ran over DSP ‘threatened his team with gun’

Running on empty

In arid Rajasthan, rivers were once revered as deities, but their status has shifted over time, said Rajendra Singh, a Magsaysay Award-winning environmentalist from Alwar, known as the “water man of India” because of his work on conserving waterbodies.

“During the 1990s, when we started protests, people from villages joined us as there was an emotional connection to the rivers. Rivers were worshipped as Narayana (God). Today, the connection has been lost. Vikas (development) has destroyed the relationship between villages and rivers,” he said. “Sand is the lungs of a river. The rivers can’t breathe as their lungs are stolen now.”

Illegal sand mining has a heavy cost. It depletes riverbeds, triggers erosion, disrupts natural water flows, and upsets aquatic ecosystems. It not only brings down groundwater levels but also impacts the quality of water.

Farmer Maniram Yadav, 55, of Kanwat village in Neem Ka Thana claimed that the last time the Katli River flowed vigorously here was in the mid-1990s. Now, it’s all hollowed out.

“My sons would hold their slippers in their hands, and fold their pants to their knees and cross the river to reach school every day,” he recalled. “But with each passing year, the water started to disappear.”

Maniram lamented that the groundwater level has also gone down drastically and the profit margin in agriculture has sunk.

Kailash Meena, another Neem ka Thana resident, has been fighting a losing battle for decades to save rivers like the Katli.

“The sand mafia has killed the soul of the river by digging deep pits all across it,” he said.

Meena was an idealistic young man in 1997-98 when he saw big crusher machines arrive in the hills near his village Bharata in Neem ka Thana.

“The water was polluted and there was dust all around. We decided to take out a two-day paidal yatra in the village to raise environmental awareness,” said Meena, 58.

The first yatra drew 150 people. Another the next year pulled a crowd of 1,000.

“Our yatra made some noise. Even a team from NDTV came to cover it in the second edition,” Meena added.

But it’s no longer easy to rally crowds against issues such as illegal sand mining. Even memorandums and petitions have not had much effect and he has faced numerous threats. Yet, he soldiers on, convinced he is fighting an existential battle.

“In 25 years of activism, I have faced 24 cases against me. Once, even terror charges were put against me. There have been six murderous attacks on me,” Meena alleged.

His battle against the sand mafia has become increasingly lonely and even his family has lost the will to participate. Filing RTIs and petitions and trying to mobilise villagers has exhausted him. He has to follow strict rules for his own safety. “I have to be home before 5 in the evening,” he said.

But many residents in Rajasthan’s mining hubs argue they are doing nothing wrong.

“It is not like stealing cash or gold from somebody’s house,” said a tractor owner who operates along the banks of the Banas in Sawai Madhopur. “People see rivers and sand as public property. How can they steal something that belongs to them?”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)