Jalandhar/Nawanshahr: It’s a bleak afternoon in Nawanshahr’s thick blanket of fog and the young cash counter clerk at a Subway is using his break time to scroll his Instagram feed. This is 18-year-old Jasskaran Rai’s favourite thing to do—checking out how his cousins are “working and partying in Canada”.

Slicing and toasting bread alongside Jasskaran, 20-year-old Surinder also keeps tabs on distant success stories on his phone. “We recently saw a man from our neighbourhood post photos of his Fortuner just purchased here. He had gone abroad, he works as a truck driver in Montreal and now he has acquired enough money to come back and buy it,” Surinder said. “That’s when I realised there is no future here. There are no good jobs.”

Surinder is currently pursuing an undergraduate programme in hotel management at a local institute, and Jasskaran attends a local business and commerce college for his bachelor’s degree. But they are waiting for bigger and better things far away from here. “All my cousins are in Canada, now I wish to go. I’m going to prepare for it,” Jasskaran said. He wants their life, even though they too are apparently trapped in a blue-collar job like him.

An undercurrent of desperation courses through Nawanshahr town, located in the heart of Punjab’s traditional immigration region Doaba. Jasskaran and his colleagues want to get out— but nothing short of Canada will do. Young people drift in and out of ‘study abroad’ and ‘immigration’ consultancies, with clear goals but uncertain paths. His cousins’ flight has now propelled Jasskaran to prepare for the English qualification test called IELTS, an acronym so popular here that it has entered local lexicon as ‘ilets’. But he also points admiringly to a reel of his friend Gurdit Singh, who has publicly posted his own illegal migration journey from South America into California.

In this town with a population of just 1,08,829, per the 2011 census, the real industry thrives on the cultural obsession with moving abroad. The town’s city square and main market are saturated with ticketing and travel agents, IELTS and student visa consultancies.

Saade pind te koi jawaan kudi haigi hi nahi, koi bhi ghar le lo (There’s no young woman in our village, look into any home). You’ll only find women who are married or who are in the process of preparing to go abroad

-Raji, Talhan resident

Police records indicate 94 immigration and ‘study abroad’ centres operating in the city alone. A police official, speaking anonymously, said these were “just the verified ones”, hinting at a vast underground network of illegal agents and institutions.

Across the state, Canada and the dream of immigration capture the social and cultural imagination. Many big names in Punjabi music and cinema either work in Canada or film abroad. Amandeep Singh, a 26-year-old Shadowfax delivery worker, sees Canada as both an alluring and a pragmatic choice because of the ease of obtaining permanent residency (PR). “I have six failed IELTS attempts,” he said, unfazed. His inspiration flows from the success stories of “singers who made it in Canada, like Karan Aujla and AP Dhillon”. Anyone can make it big once you move base there, he added.

The seductive charm of Canada is everywhere. In songs, movies, social media, and signboards with the maple leaf. And the Great Punjabi Dream is to get out of Punjab.

Conversations with young people across cities and villages revealed a consistent theme—most of the Punjabis they knew abroad worked in professions like truck driving, cab driving, construction work, and retail in grocery stores.

Also Read: Meet India’s ‘dunki influencers’. They teach you how to cross Panama jungle, Mexico border

Fantasy of flight

For many Punjabi youth, migrating to countries like Canada isn’t just about jobs—it’s a chance for metamorphosis, a shedding of the old skin. There’s a belief that the usual barriers won’t apply.

“Sidhu (Moosewala) sang about it when he said ‘Tainu pata (Do you know) this is Brampton; where everything and anything can happеn!” Amandeep said between mouthfuls of crisp jalebis outside the Studentway ‘education abroad’ consultancy office.

“I want to go the legal way, but I know some of my former schoolmates have taken dunki,” he added, referring to the illegal donkey route as stowaways, now popularised by the Shah Rukh Khan starrer Dunki.

Amandeep then praises the popular 2022 Punjabi movie Aaja Mexico Challiye, for its depiction of the donkey-flight phenomenon. “The movie has shown it all so realistically, and tells us why the illegal route can cause so many problems,” he said.

But Aaja Mexico Challiye is only the tip of the iceberg, if immigration-related themes are anything to go by. If Hindi films like Udta Punjab and Netflix series like CAT or the recent sleeper-hit Kohrra explore the region’s underbelly, commercial Punjabi cinema has long romanticised dreams of going abroad, churning out titles like Jatt vs IELTS. Even cross-border parallel cinema like the Naseeruddin Shah-starrer Zinda Bhaag tell similar stories set in Pakistan’s Punjab.

Aaja Mexico Challiye stars Ammy Virk, a big name in Punjabi cinema, along with Pakistani Punjabi actors like Nasir Chinyoti and Zafri Khan. Opening to good reviews, the movie depicts Virk’s journey as a man harbouring the ‘American Dream’ who crosses into the US border illegally via Panama and Mexico. Redditors and other social-media users have lately been making parallels between Rajkumar Hirani’s Dunki and this film, with some claiming it to be a copy given the similarities in their themes.

This culture of desperate youth is shared across the border too.

In 2013, the Pakistani film Zinda Bhaag, which also collaborated with Indian actors and was co-written by Indian-origin screenwriter and filmmaker Meenu Gaur, deals with the theme of illegal immigration and a desperate, dissatisfied set of Lahoris seeking a better life abroad. Pakistan’s first Oscars entry in over 50 years, the movie was a sleeper hit, speaking to the shared relevance of this issue across the region.

“Punjabi movies and songs romanticise migration and establish it as an intrinsic aspect of Punjabi culture,” said Dr Sugandha Nagpal, a migration studies scholar and associate professor at OP Jindal university.

“In many movies and songs, the male protagonist is a migrant or aspiring migrant and is portrayed as someone who is both a son of the soil, someone who personifies Punjabiyat, and at the same time can engage in Western consumption. The female protagonist is sophisticated, urbane, and modern while fulfilling the expectations of young women in Punjabi culture”, she added.

Dissatisfaction, desire, & the ‘influencer’ dream

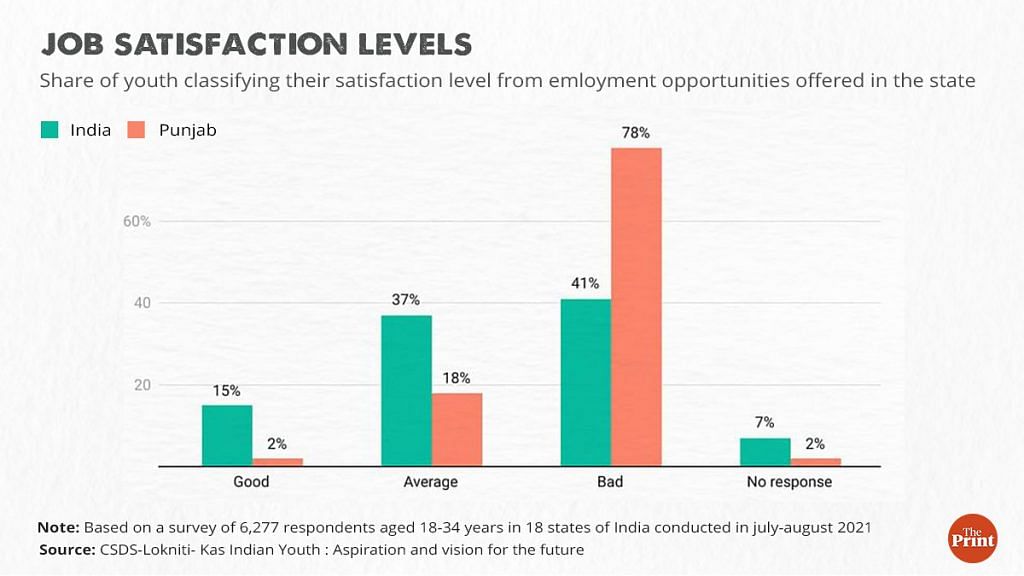

In December 2021, a survey conducted by the Centre for Studying Developing Societies (CSDS)-Lokniti and the German think tank Konrad Adenauer Stiftung found that Punjabi youth are the most dissatisfied in India with job opportunities in their home state. Only 2 per cent of the respondents from Punjab rated employment opportunities in their state as “good”, far below the pan-India average of 15 per cent.

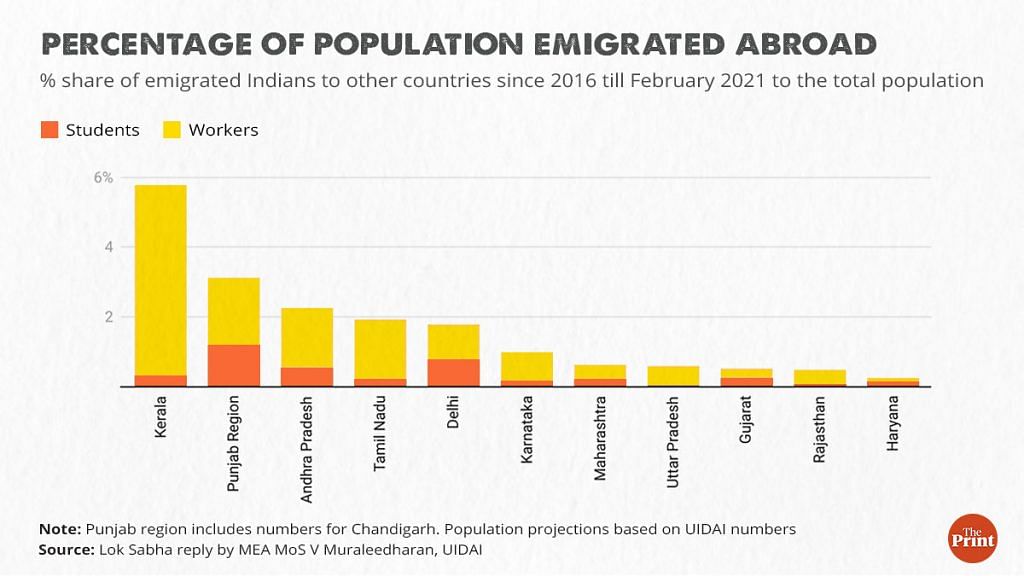

Statistics on the number of people moving from Punjab to work and study abroad are striking. In 2021, data provided by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in the Lok Sabha revealed that Punjab ranked fourth among Indian states in terms of emigration for work relative to the population, with at least 1.6 per cent of its population seeking employment abroad. When combined with the UT of Chandigarh, the number goes higher to 1.9 per cent, making it among India’s top two states with an immigrant population. The same data also shows that Punjab had the highest number of persons to go abroad for studies.

It’s little wonder, then, that looking at a Canada-based friend’s Facebook post featuring a new Fortuner, or Instagram reels of college parties abroad, feels like the answer to a deeply dissatisfied and jaded youth. Socially, the gendered experiences of women also play a big role in how fever dreams of migrating abroad are consumed by Punjabis. Young women see moving abroad to a country like Canada favourably not just because of better economic prospects, but also for safety, better individual freedoms, and more institutional regard for civil liberties.

“My daughter first tried to live and work in the UK, but when that didn’t work out despite her engineering diploma, she went to Canada. It’s not just about money. Women here are not safe. You should live here— have you ever seen a woman out past 7pm here? In Canada she is walking home at 11pm-midnight, but I don’t feel the need to worry,” said Sukhwinder Kaur, 55.

Kaur is a seamstress, living with her married elder daughter and grandson in a two-bedroom house in Talhan village on the outskirts of Jalandhar. Getting up from her seat on the sewing machine, she emphasises how out of her two daughters, it was the younger child who “put her foot down and insisted” upon going abroad without getting married.

“Initially, she wanted to stay here. She never even had a passport before the Covid year. She would say, ‘Anyone can become big if you leave this country, I want to prove myself here in India!’ But when there are no good jobs, what can be done? Itne dhakkay khaaye hain (We got pushed around so much). We tried for government jobs here, I took her for job interviews in Moga, in Jalandhar, in Chandigarh, but to no avail. Then finally she thought that it was better to spend on going abroad than being a peon here,” Kaur said.

Her 27-year-old daughter studied for an engineering diploma in the UK before finally going to Canada “because it is easier to get a PR” there. Kaur claimed that the men in her village “do not work, they just do nasha (drugs)” even as the women are “full of ambitions”. No “jawaan kudi” or young woman was left in their village, she said, because they had all left with their families.

Walking through Talhan, it is easy to see why Kaur says so. Of the four women spotted, the only one who was young and unmarried was still in high school and preparing for exams. “Saade pind te koi jawaan kudi haigi hi nahi, koi bhi ghar le lo (There’s no young woman in our village, look into any home). You’ll only find women who are married or who are in the process of preparing to go abroad and are still in +2 (class 12th). When I go to the gurudwara, I never see any young women,” said another resident Raji, 42, asking that her full name not be disclosed.

In the heart of Jalandhar city, 23-year-old Aditi Singh, newly armed with a computer applications degree, wants to move to a country with the easiest prospect of getting a work permit. Months ago, a WhatsApp exchange with a former classmate introduced her to the videos of Angel Sharma, a popular YouTuber documenting her and her partner’s Canadian migration journey. The channel, ‘Angel’s Shivam’, has more than 288,000 subscribers and over 74 million views.

“(Angel) has been filming her journey to Canada, along with her husband. I don’t know how to explain, but it’s something a lot of us want, this kind of freedom and life; she is so lucky that she gets to enjoy it with her husband,” Aditi said.

One such video—with over 1.2 million views—depicts Angel’s preparations before heading back from India to Canada, including a tearful adieu to her parents. Yet, minutes later, the mood shifts. Angel tells her audience that she will be making “ghaint, ghaint vlogs” (cool, cool vlogs) documenting the visa procedure, filing official paperwork, and her shopping sprees, urging everyone to subscribe for more.

After arriving in Canada, Angel proceeds to make multiple videos depicting her day-to-day shopping shenanigans and getting nail-extensions. Each receives at least a 100,000 views. There’s one titled “Household shopping. Shoes in just $7”, where she’s buying rugs, mats, and other “sohne, sohne” (beautiful) items and showing viewers how all of it is at a “vaddiya” (great) price. There’s another YouTube video of her trip to the Dollar Tree store, expressing excitement over every $1.5 item, leading one interested viewer to ask where this particular branch is located.

Jobs that don’t have much status back home, like construction work, offer good pay and opportunities for growth abroad, making them attractive to Indians.

Such videos can evoke deep longing. Aditi, who is currently looking for jobs in Jalandhar, said watching “influencers” like Angel and the Melbourne-based Gurkirat Randhawa has opened her eyes to the “better lifestyles and social relations” abroad.

Conversations with young people across cities and villages revealed a consistent theme—most of the Punjabis they knew abroad worked in professions like truck driving, cab driving, construction work, and retail in grocery stores. Truck driving, especially, is seen as a profession synonymous with the region across the globe. Amandeep, the delivery worker, cited Rahul Gandhi’s video of going from Washington DC to New York with Taljinder Singh Gill, a truck driver and immigrant in the USA.

Amandeep pointed out that, unlike India, truck driving in the US or Canada is a “well-paying job with dignity, where you can easily earn as much as Rs 5 to 6 lakh a month”.

On Instagram, many immigrants upload reels and photos of their trucks, including popular ‘migrant influencer’ Ankush Malik. Subway employee Surinder echoed the sentiment that jobs that don’t have much status back home, like construction work, offer good pay and opportunities for growth abroad, making them attractive to Indians.

Praying for escape

The village gurdwara in Talhan is a must-stop for anyone with an escape dream. At this 150-year-old site, the Shaheed Baba Nihal Singh gurdwara, devotees make offerings not of flowers and sweets, but of toy airplanes and helicopters.

Amid the crowd, 36-year-old Amarinder Singh, who serves halwa or ‘kadha-prasad’ at the site, whips out his phone to show a video clip of Shah Rukh Khan and Dunki director Rajkumar Hirani.

“The footfall at Talhan Sahib has increased since 17 or 18 December, after SRK mentioned us and this video went viral on Facebook and WhatsApp groups. All that’s left is Shah Rukh himself coming here!”

Every day, hundreds flock to make what Baljeet Singh, the gurudwara’s manager, dubs “foreign jaane ki muraadein”—prayers for flying colours in the IELTS exam, visa approvals, Canadian PRs, green cards.

Flanking the gurdwara are shops and street vendors selling plastic planes. The management estimates that until a few months ago, up to 5,000 toy planes were offered here each week. However, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) forbade the practice in August 2023 after a visitor offered a model airplane at the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Devotees here continue to buy and offer the plastic planes, albeit in a designated area now set aside by the gurdwara management. Footfall dipped during the winter, but the immigration buzz has returned, thanks to Dunki and Shah Rukh Khan’s reference to the village during promotions for the film.

However, even for those whose immigration prayers are seemingly answered, not everyone ends up in Canada, the UK, or the US.

The UAE—which draws the greatest number of Punjab’s emigrants— attracts the highest proportions of Dalits (52 per cent), landless households (41 per cent), and those with the lowest standard of living (72 per cent).

Also Read: Punjabi illegal migration to US relies on asylum letters. And one MP is doling them out

Hierarchy of destinations & caste factor

There is a totem pole of destinations for the desperate, and if the US and Canada are at the top, new horizons are propping up on the map for those willing to compromise.

“There is no way to settle in the UK, so I’m going to Cyprus,” said 30-year-old Amandeep Singh Chouhan. A BTech graduate and a former manager with a leading app-based delivery platform, he is all set to shift and invest capital to start a business in the European island nation. He cites the promise of a “better life, better weather, and mobility” in the region as the reason for his change of heart.

Chouhan’s story is not uncommon. In Chandigarh’s bustling Sector-17 market, at least two consultancies displayed a row of shiny brochures touting accredited programmes of study and state-of-the-art campus facilities in the American College. But look closer and college is nowhere near the US, but in the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

If the brochures and signs outside ‘study abroad consultancies’ are anything to go by, then a growing number of Punjabis are now choosing destinations like Cyprus, Malta, Croatia, Qatar, and Eastern European countries like the Czech Republic over the traditional Canada route. They may not be top of the list, but still have the lure of “a better life”.

It helps that some East European countries, along with Italy, are also seen as gateways for illegal or undocumented migration, with reports of agents and traffickers being apprehended for donkey flights via these routes. While people do choose to work and settle in countries like Italy or Cyprus, these are often seen as stepping stones rather than final destinations, with the ultimate goal of reaching Canada, the US, or the UK. Farming, dairy, and cattle-rearing have famously become common occupations for Punjabi migrants in Italy.

If we rank the destinations by upward status, the top choice is the United States if you have the resources. Many go to Canada with the ultimate dream of going to the US

-Prof Aswini Kumar Nanda, economics and migration research scholar

Close to 11 per cent of households in Punjab reported at least one current international out-migrant, according to a 2015 analysis of migration patterns by the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (CRRID) in Chandigarh and the National Institute for Demographic Studies in Paris. But this survey of over 10,000 households debunks the popular perception of Canada being the primary destination for Punjabi migrants. Many more land up in the UAE.

While no recent official data is available from the region, the report further contradicts the Canada stereotype by showing that Asia is the top destination for Punjab’s migrants (45 per cent), followed by Europe (26 per cent) and North America (18 per cent).

The study also suggests that caste dynamics heavily influence both destination choice and reasons for migration.

Nanda noted that the Gulf meant “lower-grade job opportunities and work” and many Dalits ended up there in “labourer class” jobs.

Although upper-caste populations, particularly Jatts and Khatri Sikhs, constitute the largest group of out-migrants at more than half the total share, Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Scheduled Castes (SCs) also represent significant proportions at 23 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively.

Paradoxically, the emigration rate is highest among OBCs (41 per 1,000), followed by upper castes (37 per 1,000) and SCs (14 per 1,000). But the most striking difference lies in the destinations where these communities end up.

The UAE—which draws the greatest number of Punjab’s emigrants— attracts the highest proportions of Dalits (52 per cent), landless households (41 per cent), and those with the lowest standard of living (72 per cent).

In contrast, the study found, Canada is most preferred by non-Dalit and non-OBC castes (17 per cent), households owning at least 10 acres of agricultural land (25 per cent), and those with the highest standard of living (16 per cent).

“The Doaba region has one of the highest populations of Dalits in India, many (of whom) also have small-sized land holdings,” explained economist and migration studies scholar Aswini Kumar Nanda, one of the authors of the CRRID study. He told The Print that deprivation is a strong driver of migration, leading many to even “borrow money or resources” just to leave the country.

“Borrowing from friends/relatives is highest among immigrants who are at the bottom of the wealth index (74 per cent) and are from the SC community (71 per cent). This can be due to lack of productive assets, which restricts their access to commercial banks that offer funds at relatively lesser costs and risks compared to money lenders,” he said.

Nanda noted that the Gulf meant “lower-grade job opportunities and work” and many Dalits ended up there in “labourer class” jobs. “If we rank the destinations by upward status, the top choice is the United States if you have the resources. Many go to Canada with the ultimate dream of going to the US.”

There’s no value of learning here, there are no jobs. No matter what caste

-Krish Bali, BSP disstrict secretary, Nawanshahr

In Nawanshahr, the district office of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) looks somewhat out of place among a row of study-abroad centres lining the Phagwara-Mohali expressway. For Krish Bali, the BSP’s district secretary, immigration remains a burning concern. While most Dalit families have historically been denied access to land ownership and financial resources, Bali pointed out that this has not stopped anyone from aspiring to Canada or other foreign pastures. “There’s no value of learning here, there are no jobs. No matter what caste,” he said.

But it is widely understood even on the ground that caste does play a role in the visa stamp. “Canada is mostly for Jatt boys, those from marginalised castes tend to go to Australia, Eastern Europe, or the Gulf,” said 18-year-old Jaspreet, who is not a member of a dominant community.

Jaspreet attends IELTS classes daily and says she and her friends all hope to make it abroad after completing school even though none of them are awash in finances. The pay-offs for settling abroad— anywhere—are worth it in the long term, according to her. Jaspreet isn’t obsessed with Canada, suggesting it’s the dominant Jatt Sikhs who fetishise it in films and music.

Financial duress, exploitative ‘diplomas’

Not every move overseas unfolds like a fairytale. It doesn’t guarantee success, and families often continue to struggle with paying the costs involved, resulting in resentment and disillusionment.

Vinod Kumar, a 53-year-old scrap dealer who moved to Punjab from UP’s Kasganj, knows this all too well. The eldest of his five children, a son, hoped to move to Canada, but these aspirations were dashed by a low IELTS score. “So, finally, he opted for the UK and left two years after +2, when he was 20. But I don’t know what he is doing, he only calls his mother and siblings and he seems extremely depressed,” Kumar said.

To sustain his son’s “initial period” of stay abroad, Kumar sold off whatever land the family owned in UP—a step quite common among families with few other finances.

“Even if it’s just 1 killa, that helps with Rs 8-10 lakh to fund the first year of a diploma. Then, the child can try to find a job, or do something or the other there to sustain (themselves),” he said. Kumar is relieved that his other children have resolved not to leave.

People will take a loan, beg, or borrow—and this is to go to some diploma programme in Canada that has no recognition or value

-Sukhmeet Bhasin, journalist

Apart from financial duress and the risks of selling land or taking loans, dubious degree programmes and unregulated workplaces can lead to deportation. Last month, the Canadian government doubled the minimum cost-of-living requirements for foreign students due to the country’s own housing and inflation crisis. Strained geopolitical relations with India since the Hardeep Nijjar killing haven’t helped either. Reports indicate a 40 per cent drop in study permits for Indians since last July.

These setbacks come after two major jolts for Indian students, especially Punjabis, in 2022 and 2023. First, nearly 2,000 students were left in the lurch after three Quebec institutions were declared bankrupt and shut. Then came a college offer-letter scam that affected over 700 students and nearly led to their deportation.

Twenty-three-year-old Simran Batth from Sangrur was one of those affected. His family sold their 5 acres land as ‘security’ for his business degree in Montreal, Quebec. When the college shut down, Simran had to run from pillar to post, even resigning himself to doing his MBA back in Punjab. Finally, the Canadian authorities intervened to stop the students’ deportations.

Sukhmeet Bhasin, a journalist who has been covering the issue of immigration for years, railed against the scourge of families “going in for useless diploma programmes”. These diploma courses typically offer skills-oriented learning for a specific subject like business administration or computer analytics but are shorter and less academically rigorous than a full-fledged degree programme. Akin to ‘certificate courses’, diploma programmes are relatively easy to get into but usually lower in value in the job market.

“People will take a loan, beg, or borrow—and this is to go to some diploma programme in Canada that has no recognition or value,” Bhasin added.

Despite all the nightmarish stories, however, overseas dreams persist across caste and class. Ved Pal, a 50-year-old jalebi-vendor whose cart sits outside one of Nawanshahr city’s better known IELTS centres, beamed that taking a loan of close to 30 lakhs “paid off” for him. His 24-year-old son is now settled in Canada after getting a “technical degree”. For Pal, his son’s journey abroad represents an “upgrade” from his own migration from Dehradun to Punjab decades ago.

Also Read: Punjab youth are unemployable. The state doesn’t have a Bangalore, Hyderabad, Pune or Noida

Ghost towns

Every other doorway seems to be locked and young faces have all but disappeared in many villages across the Doaba region, as well as in places like Khatkar Kalan, Talhan, and Kotli Than Singh.

In Khatkar Kalan, Bhagat Singh’s ancestral village, a disquieting stillness descends as the sun goes down despite its status as a tourist site and “model village”.

At just 6 pm in the last week of December, the village seemed deserted, barring a group of middle-aged men huddled by a bonfire near the park and library. Amrik Singh, 45, pressed groundnuts between his palms, and then gestured to a row of neat pucca houses. “This one has gone to Norway. Those two are in Canada. This family just left for America,” he said. The houses are now dark and empty, with only a caretaker checking in now and then.

The former sarpanch, Sukhwinder Singh told ThePrint that the local population would be close to 1,200-1,300, with “at least double, if not triple” of that figure having moved abroad.

It’s the same story in villages like Talhan and Bhadas. Young men and women are scarce and many houses are locked or under caretakers. With a handful of crumbling Partition-era homes in the mix, reminders of another exodus, they almost feel like ghost villages after nightfall.

Jai Singh, another middle-aged resident of Khatkar Kalan, ruefully recounted how the Aam Aadmi Party’s Bhagwant Mann chose this village to be sworn in as Chief Minister in 2022. “Even the next year, Mann addressed villagers on Bhagat Singh’s birth anniversary and made promises that his government would start a ‘reverse migration’ in Punjab,” he said.

Yet, the multitude of locked doors and compounds in the village tells a different story. “Whoever has gone, has gone, never returned. How can you reverse this?” Jai Singh asked. “Why return? There is no looking back. What is there for anyone here?”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)