Surat: On a curved panel monitor, a frame zooms into a busy road. From inside a parked tempo truck, a driver flings an empty packet of gutkha on the road. But such a blatant breach of public hygiene can’t go unnoticed in Surat. It is a crime caught on CCTV camera and thoroughly reviewed inside a sprawling control room by hawkeyed Surat Municipal Corporation staff. There’ll be consequences. The vehicle’s origin is traced through the Regional Transport Office, a challan is generated, and the SMC’s zonal branch quickly delivers it to the registered address.

This is just one of the many ways in which the SMC’s Integrated Command and Control Centre (ICCC) maintains global standards of cleanliness in the bustling port city of nearly 75 lakh people. And it takes a lot more than door-to-door garbage collection, sweeping roads, or shepherding stray animals.

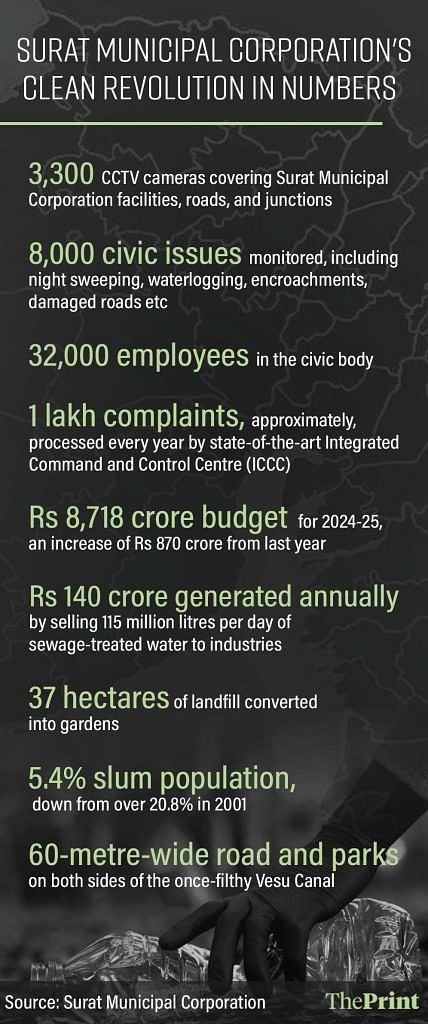

A robust network of state-of-the-art technology and infrastructure works constantly behind the scenes to ensure that no waterlogged drain or garbage pile goes under the radar. This combined effort of boots on the ground with high-tech surveillance earned Surat the government’s cleanest city award last month. After trailing in second place for three years in the Swachh Survekshan survey by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Surat is finally reigning in the top spot alongside Indore.

Every door-to-door (trash collection) vehicle is equipped with GPS. They have a route plan—location, time, how many houses are supposed to be covered… And if that vehicle misses any of the things, there is provision of a penalty

– Shalini Agarwal, SMC commissioner

But the textile and diamond hub couldn’t always brag about its clean roads, beautiful parks, and fully treated wastewater. Thirty years ago, in 1994, Surat gained notoriety for its open drains and uncollected garbage, which led to a pneumonic plague outbreak that killed over 50 people and triggered a panicked exodus. The plague was contained within a week, but it left lasting lessons. Since then, the city has risen from the ashes.

Today, not a single open drain mars the cityscape. Visitors are welcomed by roads and streets adorned with flowering plants, bushes, and trees. Traditional murals and intricate graffiti decorate roadside walls and overbridges. Traffic jams are a rarity. Surat’s transformation into a 21st-century city is built on a solid foundation of infrastructural development, now amplified by technology.

“Cleanliness is not just about sweeping the roads. It’s about providing good infrastructure to the citizens so that the quality of life is maintained,” said Surat Municipal Corporation commissioner Shalini Agarwal.

The Surat urban body has dedicated itself to its goal of delivering world-class physical infrastructure to Suratis and it’s not holding back in exalting its achievements.

“While the population of Surat has doubled, the slum population has decreased from 20.8 per cent (in 2001) to 5.5 per cent,” IAS officer Agarwal said. “When the current Prime Minister Awas Yojana (a housing scheme for the poor) gets completed, the slum population will drop by 4.5 per cent.”

Stepping into the ICCC’s giant main control centre is like being transported to an ISRO control station.

Also Read: Gujarat’s true crime drama—flying gold coins, fleeing labourers, police chase, & an alert ASI

A high-tech war room

With its arched doorways and high-ceilinged rooms, the headquarters of the Surat Municipal Corporation exudes an old-world aura. Housed within a 17th-century building known as Mughal Sarai, this Old City structure served as a travellers’ inn during the time of Shah Jahan and later functioned as a colonial jail before accommodating the SMC in 1867. Inside, administrative offices are cluttered with heaps of files, and busy clerks shuttle paperwork much like in any bureaucratic outpost.

But the corporation’s real muscle lies elsewhere: the sleek, futuristic Integrated Command and Control Centre (ICCC) in the upcoming Althan locality. This glass-walled war room, armed with cutting-edge technology, acts as the brain and eyes behind Surat’s spic-and-span status, continuously monitoring day-to-day public services related to cleanliness, hygiene, and sanitation. Though having an ICCC is mandatory under the Smart Cities Mission, the cash-rich SMC boasts one of the biggest and most advanced setups in the country.

Stepping into the ICCC’s giant main control centre is like being transported to an ISRO control station. A massive 1,000 square foot digital wall dominates the space, with a panel saying ‘Surat Emergency Response Centre’. It’s a reminder that the centre can morph into a crisis command post if Surat is hit by a disaster like an earthquake, cyclone, or flood.

But on normal days, 50 workers keep vigil behind their monitors. Some track littering incidents, others check if the city buses are running on time, and some oversee garbage truck schedules. From monitoring damaged footpaths and drainage water flow to detecting illegal hoardings, around 3,300 CCTVs feed data to the urban body.

“Each of our services is integrated with technology and monitored at the ICCC,” commissioner Agarwal said.

The ICCC, in operation since 2016, has two such rooms, of which one is currently in use for day-to-day activities.

The centre also handles complaints registered by Suratis through various channels: a toll-free number, the SMC app and website, or even walk-in visits. A centralised complaint management system collects all the complaints and tracks the redressal of the grievances.

“In a year, we receive around 1 lakh complaints,” said a member of SMC’s IT department.

While these grievances offer a glimpse into the issues on the ground, members of SMC’s IT department insist that they are not necessarily a reflection of the urban local body’s service quality. Team members claimed they often get multiple complaints about one issue from certain areas where people are more “vigilant” while there tend to be fewer grievances from pockets where people are less educated.

“But you get a picture and a sense of which SMC services are good and which services people have issues with. You get the flavour and you get an idea of the actual scenario,” SMC’s IT department head Jigar Patel said.

Complaints also vary by season, with the monsoon often bringing reports from citizens of damaged roads and mosquito breeding. All the data collected at the ICCC is analysed to prepare for future needs.

“We study what kind of complaints are received at which time of the year. It gives us an idea of what types of problems are faced in different parts of the city,” Patel said. “If there is a drainage-related complaint, it might turn out that the capacity of the installation has been exceeded. It’s an indication to the engineering team to augment the particular drainage line.”

Surat’s cleanliness victory isn’t just about top-down decrees and ramped up surveillance, but also community action.

Plague to sanitation pioneer

Surat’s transformation into a beacon of cleanliness traces back to the bleak events of the 1994 plague outbreak. The task to reboot the city fell on IAS officer SR Rao, who took over as SMC commissioner in 1995. His work has since become the stuff of legend, both within the SMC and among the populace of Surat, even earning him a Padma Shri.

“The fundamental changes that SR Rao brought about ultimately led to the foundation of where we stand today,” a doctor who works with the SMC said. Previously, the SMC allocated a significant portion of its grants to public welfare initiatives like water supply and schools, according to the doctor. However, in the aftermath of the plague, Rao strategically refocused their efforts on sanitation, a core function of municipal bodies. “When it comes to cleanliness, sanitation, and hygiene, the real journey could be said to have begun with SR Rao,” he added.

From a street hawker to a senior citizen, Indoris have a consciousness and awareness about cleanliness and waste segregation which Surat residents are yet to achieve

-Akash Bansal, founder of Project Surat

–

After taking charge, Rao implemented an administrative overhaul, bolstered manpower, and allocated increased funds for sanitation. Surat also pioneered mechanised night sweeping under his leadership in the 1990s. Even after his tenure, the SMC kept up its momentum, launching door-to-door garbage collection in 2004, a decade ahead of the Swachh Bharat Mission.

Two decades on, tech has become a major driver of timely garbage collection. The tiniest movements of all the garbage pickup vehicles are monitored at the ICCC.

“Every door-to-door vehicle is equipped with GPS. They have a route plan—location, time, how many houses are supposed to be covered are specified,” Agarwal said. “And if that vehicle misses any of the things mentioned in the route plan, there is provision of a penalty and further actions.”

But Surat isn’t resting on its laurels. The SMC’s 2024-25 draft budget, a record-high Rs 8,718 crore, reflects the city’s vision for enhanced infrastructure, tourism, flood control, and overall liveability.

While property tax remains the biggest source of the SMC’s revenue, it also generates income from waste.

For instance, the corporation earns Rs 140 crore annually by selling 115 million litres per day (MLD) of treated sewage water to industries. This year’s budget anticipates an increase in capacity to 275 MLD. “The SMC was one of the first municipal corporations in India to treat sewage water and supply it to the textile industry,” Agarwal said.

In addition to this, the SMC operates several waste management plants, including facilities for converting plastic into polymers for textiles, repurposing construction waste into paver blocks, and processing wet waste into biogas and manure.

All legacy waste has been eradicated, according to Agarwal. Days before Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Surat Diamond Bourse last December, the SMC converted 37 hectares of a nearby solid waste landfill into lush gardens. Another major beautification project was the revitalisation of the once-decrepit Vesu Canal area.

While many cities began focusing on cleanliness only with the Swachh Bharat Mission, Surat had already established a well-oiled system comprising nine zones, each overseen by a deputy commissioner and a health commissioner.

“With the coming of the Swachh Bharat Mission, we used its provisions to set up other major interventions. As the Mission moved from low-hanging fruits to difficult things to more behavioural changes, we tried to stay one step ahead of it,” the doctor said.

Also Read: Gujarati Muslims struggle to buy Hindu property. Disturbed Areas law weaponises real estate

Changing attitude of Suratis

Surat’s cleanliness victory isn’t just about top-down decrees and ramped up surveillance, but also community action. Citizens aren’t merely toeing the line—many are also taking the reins.

Akash Bansal, a 32-year-old businessman, is one such resident. Back in March 2019, Bansal arrived early for a friendly football match on Dumas beach when he noticed a pile of trash on the seashore and decided to involve family and friends in cleaning it up. This took off into a grassroots movement, ‘Project Surat’ , to clean up the dirty pockets of the city.

Bansal credits the rise of civic consciousness in Surat to SR Rao’s vision. “We are still following his footsteps,” he said.

Retired merchant navy officer Ashok Gondalia, who has participated in some Project Surat’s cleanliness drives, stressed the importance of “cooperating” with the SMC for effective change.

“We gather trash from areas along the Tapi riverfront and the Dumas beach. Then we upload the images on the corporation’s app. Their people come and take it. That way, SMC is efficient,” he said.

While cleanliness issues do persist in certain public spaces, residents widely commend the SMC’s competence in garbage collection and local sanitation. “If a service stops or is irregular, one complaint to the SMC resolves the issue,” said a resident asking not to be named. “There are no major problems.”

Bansal, who has experience working in the field of sustainability, said Surat’s cleanest city award was long overdue. “SMC is competitive and has the right infrastructure. They always wanted recognition at the national level,” he said.

However, Bansal added that Indore still has an edge over Surat—full-scale buy-in and participation from residents.

“From a street hawker to a senior citizen, Indoris have a consciousness and awareness about cleanliness and waste segregation which Surat residents are yet to achieve,” he said, noting that waste segregation and littering remain problem areas.

Bansal conjectured that the issue might stem from Surat’s demographics, specifically its large migrant population. SMC officials also cited Surat’s population size as a major challenge.

The city has nearly 75 lakh people concentrated in 461 sq km, compared to Indore’s approximate 33 lakh in 530 sq km and the third cleanest city Navi Mumbai’s 15 lakh in 344 sq km. Officials said the city has a floating population of 15-20 lakh, with migrant workers coming from various states, including Maharashtra, Odisha, UP, and Bihar.

“Ultimately, what we are trying to create is a sense of ownership and belongingness—that ‘it’s my city’,” an SMC official said. “That can come easily when it’s a homogenous population born and raised in the city rather than someone who is here only for their livelihood.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)