New Delhi: When Subodh’s mother was bitten by a snake, slim and barely a foot long, his first instinct wasn’t to take her to a hospital. Instead, he rushed her to a faith healer in Murad Nagar, where her wrist was stroked with a stick—even though the bite was on her foot.

“We don’t trust hospitals. We trust healers, herbs, and Ayurveda,” he said while managing his corner store in Morta, a village in Ghaziabad’s Raj Nagar extension.

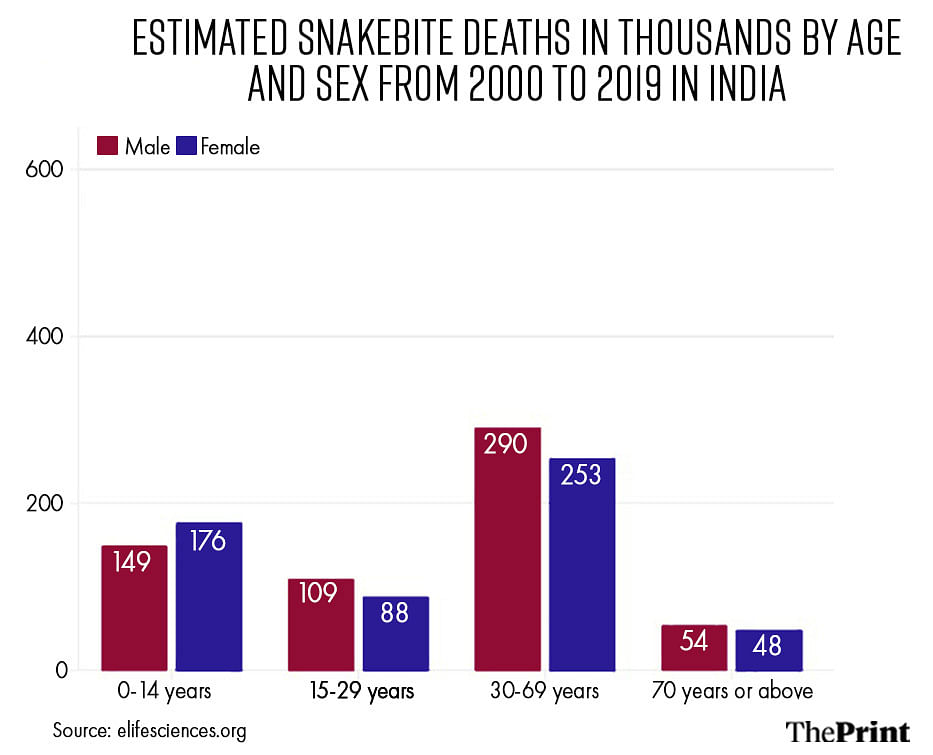

Snakebites in India are mostly brushed away as a rural, poor-people problem, but the numbers are staggering. More Indians die from snakebites than from all other wildlife encounters combined, and the death toll surpasses that of dengue and malaria deaths, which receive mission-mode attention from the government. BJP MP Rajiv Pratap Rudy reported in Parliament last week that as many as 50,000 people die each year from snakebites, though surveys suggest the number is closer to 58,000.

The issue rarely makes headlines despite India being the worst-affected country in the world. Data from a 2020 national mortality study shows that 94 per cent of snakebites occur in rural areas, and 77 per cent of the deaths happen outside hospitals.

It is a story wrapped up in mythology, superstition, and abysmal public health infrastructure. Primary health care centres are just not equipped with the necessary resources or trained doctors to treat snakebites in time.

Subodh’s mother survived the bite—it was a non-venomous snake—but the family credits her recovery to the faith healer.

“A snake is a snake, regardless of the amount of poison. Whether it’s small or big, the effect is the same,” declared Subodh.

This lack of awareness has only exacerbated India’s deadly snakebite crisis. In villages, where snakebites are rampant, people eschew doctors for faith healers.

Earlier this year, the government launched the National Action for Prevention and Control of Snakebite Envenoming, aiming to cut the mortality rate in half by 2030. The deadline is ambitious, according to Dr Priyanka Kadam, founder of the Snakebite Healing and Education Society. The Union Health Ministry also introduced a snakebite helpline to provide “immediate assistance, guidance, and support” to victims.

However, these policy changes have done little to significantly impact mortality rates, while states continue to disburse substantial compensation—Madhya Pradesh alone paid out Rs 231.16 crore between 2020 and 2022.

A roadblock in policy implementation is the place snakes occupy in myths and popular culture, nudging people toward healers instead of doctors. Socially validated superstitions, such as snakes seeking revenge or residing in nightmares, further drive people away from medical treatment.

It’s not a shortage of anti-venom, but kinks in distribution networks and overworked staff at community health centres that have led to a system that cannot cope, said Kadam. There needs to be a neater, more efficient way to procure anti-venom. According to government data from 2015, treatment at hospitals was sought within 4 hours of the bite in 55.69 per cent of cases. While patients were frightened, “no local or systemic symptoms” had appeared.

“India is a country of belief systems. We come across many educated people who think the solution is faith healing,” said Dr Kadam. “If people are able to identify snakes, half the job would be done.”

Also read: He is Bihar’s ‘Snake Man’ and he won’t stop till he rescues the very last one

Snake rescuers

By virtue of its rural character, snakebites are not a topic of discussion in cities. But snakes receive far more attention in urban areas. Panic is instantaneous, fear is intense –– and a phone call is inevitable.

“Whether the snake is crossing the road or sitting in their bedroom, they’ll call us,” said Annakanna, a snake-catcher in Hyderabad who has been rescuing snakes for two decades.

Annakanna is part of a volunteer group, Friends of Snakes, which receives between 200 and 300 calls every day. So far, the group has rescued over 10,000 snakes in Hyderabad alone, relocating them to adjacent forests in collaboration with the Telangana Forest Department.

“It’s because of the bandicoot or rodent population. They’re creating channels for snakes to travel from one place to another,” said Annakanna.

Following an article confirming the accuracy of their numbers, Friends of Snakes is set to be listed in the Guinness World Records for rescuing the most snakes. No organisation operates on the scale they do, Anakanna said with pride.

Despite his extensive experience, he has never been bitten by a venomous snake, although he has been nipped dozens of times.

The snake-obsessed group, with dozens of fascinated freelancers as members, witnessed its moment of glory in 2014 when they rescued an Indian Egg-eater from the outskirts of Hyderabad. This harmless, yellow-black snake was believed to be extinct since 1969.

“If we hadn’t rescued it, it would have been killed,” said Anakanna. The group took the snake for research purposes and then swiftly released it in a nearby forest, where it can continue to be monitored.

Also read: Snakebites aren’t just lethal. In rural India, it means debts of lakhs to victims, families

Rural problem, neglected disease

It was only in 2017 that snakebite envenomation was categorised as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization (WHO), after being removed from the list in 2013. Once considered a problem of the poor, snakebites have loomed large on the periphery, only occasionally entering mainstream discourse, experts say.

“It affects the most vulnerable sections of society. That’s why it’s been neglected all these years. Who will fight for the rights of poor people?” said Dr Kadam. “People who don’t have medical access are fatalistic. They don’t believe it’s a treatable situation.” She has been working with snakebite victims for the last 14 years.

State governments pay compensation under the Disaster Management Act –– and families receive approximately eight times less than what they would in case the victim had been killed by a wild animal. According to a report by the India Development Review, snake bites have been “misclassified” as a natural calamity.

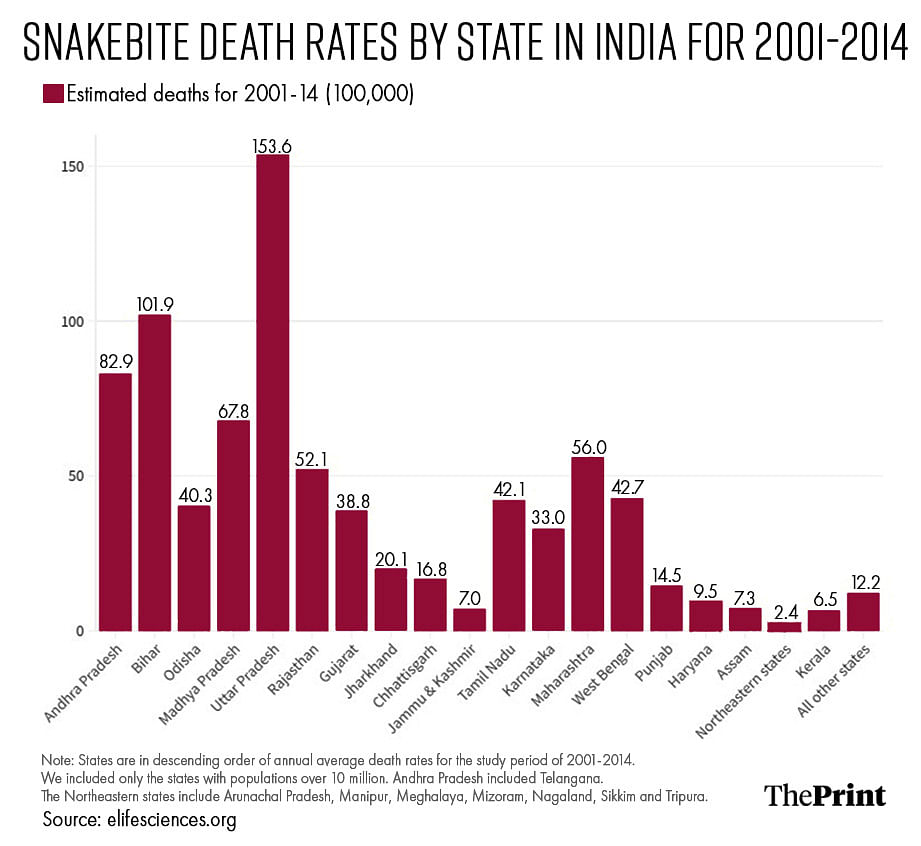

In March, Karnataka became the first state to classify snakebites as a notifiable disease. This means bites must be reported under the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (ISDP). This move has been welcomed as a step toward better documentation. A 2020 study revealed that Rajasthan and Gujarat recorded the highest number of bites from 2001 to 2014. In 2016, a health ministry document highlighted that Uttar Pradesh faced the most severe crisis, with 8,700 deaths reported annually.

A director at the Humane Society of India hailed Karnataka’s decision as the start of a “snowballing effect”, hoping other states will adopt similar measures.

For the people of Morta, snakes are a part of life. They are wary of them, but view their presence as inevitable and are frustrated by the inconsistent financial compensation, which varies by state. In Uttar Pradesh, the Disaster Management Authority provides families with Rs 4 lakh in case of a death. Between 2019 and 2023, 3,348 people died from snakebites.

A 19-year-old woman from Morta, whose family wished to remain anonymous, was bitten by a snake while lounging on a charpai. The snake had entered their cooler, and she didn’t realise what had happened.

“It’s been a year. We handled the treatment by ourselves and didn’t get anything from the government,” said her sister.

Last month, two children in Dhanora Gusai, a village in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district, were bitten by a common krait while asleep. The five-year-old girl, initially mistaken for having a mosquito bite, was declared dead on arrival at the Government Medical College in Nagpur. The ten-year-old boy survived.

In the first eight months of 2024 alone, the Nagpur hospital reported 200 snakebite cases, according to data shared with ThePrint. There were two deaths.

However, procuring accurate data and notifying deaths from snakebite incidents remains difficult, and many cases go unreported.

“No number is reliable. Our systems aren’t fully automated. If someone dies before reaching the hospital, their death isn’t recorded,” explained Dr Kadam. Legally, deaths should be reported to the local police station, but bureaucratic hurdles like post-mortems and death certificates often deter families. Many are unsure if the snakebite is the cause of death.

According to a 2019 study published in the National Library of Medicine, 97 per cent of snakebite deaths in India occur in rural areas.

“The government still isn’t awake. We go to school and colleges to hold awareness programmes, but receive no support from the government. They need to be more aware,” said Bhandakkar.

Awareness programmes focus on the fundamentals—keeping rats out as they attract snakes. Villagers are told to ensure there are no gaps between homes and the ground and harvest produce are not stored inside houses.

Also read: ‘To live is to kill’ — a Malabar pit viper and gliding frog affirm nature’s basic law

The rise of faith healers

In Katta, a village near Nagpur, volunteers with a local NGO conducted a sting operation. They simulated a snakebite wound and went to a temple where a healer practiced.

Upon arrival, they were told to wait. A man emerged from within the temple complex, slithering toward them and using his arms to move forward.

“He said there was a snake inside him,” Nitesh Bhandakkar, who runs the NGO, told ThePrint. The man, dressed in a red vest, then began to suck on his leg—supposedly extracting the venom. He was the snake and the venom was being returned to its place of origin.

The man has since been booked under the Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifices and other Inhuman, Evil, and Aghori Practices, and Black Magic Act (2013) and is currently in jail.

What works in favour of these homegrown, socially sanctioned healers is the higher likelihood of encountering non-venomous snakes. Out of 300 snake species in India, only 17 are considered “medically important,” causing serious harm like vision impairment, excessive bleeding or renal failure. This, combined with inadequate medical infrastructure, creates an ideal incubator for the proliferation of healers.

In Morta, where residents frequently see snakes, their identification skills are limited to size and shape. They encounter snakes in their homes, fields, and on shop-lined streets. Stories of snake sightings, and bitings, pass from one person to another—a girl bitten in her classroom; a woman bitten on her way to the toilet. Sightings become frequent during the monsoon season.

The nearest government hospital is about a 20-minute drive away, but when a 19-year-old woman was bitten by a venomous snake last year, her family claimed the hospital didn’t have anti-venom. They had to travel 40 km to Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital for treatment.

The trust deficit between villagers and hospitals further perpetuates the reliance on faith healers who continue to thrive.

According to Dr Kadam, even the spectacled cobra, one of the “Big Four” venomous snakes, may administer a “dry bite” and not inject venom. If there are no clear symptoms, healers can smoothly take credit for a recovery.

It took Golu, a former healer from Nagpur, a venomous snakebite to see the error of his ways.

“I’ve given dozens of people herbs and a paste made from trees,” Golu said. His career ended abruptly when he was bitten by a Russell’s viper and needed to be rushed to the hospital for treatment with polyvalent anti-venom, which addresses bites from the Big Four venomous snakes.

“I was probably treating non-venomous bites. Now I’ve realised [the difference],” he said.

Bigger battle is superstition

Snakes have been mythologised and eulogised—mostly though, they have been demonised. For awareness activists, their primary battle is against superstition.

Snakes are portrayed as cunning, malicious, and a force that must be defeated. Rudyard Kipling’s Rikki-Tikki-Tavvy, inspired by Panchatantra folktales, depicts a mongoose defeating cobras who resent humans. The story ends with the mongoose ensuring no snakes return.

Bhandakkar, who works with NGOs to educate victims and facilitate treatment, says it’s an uphill task convincing villagers to visit hospitals first. Over the years, he has received bizarre complaints of strange dreams and random changes in taste, which villagers attribute to the spread of poison. These symptoms, though varied, can often be fear-induced and psychosomatic.

“It’s because of movies. There’s too much superstition around snakes,” said Bhandakkar. “Snakes have been turned into toys for entertainment. We’re in 2024.”

More often than not, timely medical intervention can be expensive. Last week, when Kavita Selokar, a farmer’s wife from a village near Nagpur, was bitten by a Russell’s viper while working in the cotton fields, her family initially sought help at a private medical facility before moving to the local government hospital.

“I am a graduate, my wife is a graduate, and so are our children. We don’t believe in faith healers,” said her husband Dashrath Selokar. “I immediately took her to the hospital.”

After initial treatment at a private facility, they racked up a bill of Rs 40,000—beyond the family’s means. Kavita is now receiving treatment at a government hospital in Nagpur, where she’s running a high fever. Doctors have prescribed ten injections and estimate a full recovery within a month.

Meanwhile, in Morta, residents are puzzled by the concept of snake-only NGOs. For them, snakes are not a problem but rather a natural part of life.

“It’s the dogs that are a menace here. We can barely leave our homes,” said one resident.

(Edited by Prashant)