Deorala/Jaipur: Thirty-six years ago, Roop Kanwar was burned alive in the name of sati. Today, fresh red chunris, coconuts, and burnt agarbattis still surround her makeshift shrine, drawing sati pilgrims from all over Rajasthan, UP, MP and Gujarat. And villagers are still saying ‘mandir wahin banayenge’, demanding a bigger, grander temple.

And yet, a Rajasthan court has shockingly acquitted the last men accused of glorifying her death.

Over the years, Rajasthan’s courts have made one thing clear—no one forced 18-year-old Roop Kanwar into the flames, nor did anyone celebrate her death. The state government hasn’t challenged this view, and this month’s final acquittals have only strengthened her status as Sati Mata in her village of Deorala, 80 km from Jaipur. For villagers, she’s a goddess—and a draw for visitors.

In the sun-baked Shekhawati region, Deorala is dotted with old havelis of Rajput and Agarwal clans. The spot where she burned with her dead husband on 4 September 1987 remains a symbol of Rajput pride even today.

“A temple should be built at this spot, since this sati happened before the (1987) law. People’s beliefs are attached to this place,” said Anand Singh Shekhawat, a priest in the village.

Building sati temples is monetarily beneficial… It brings development and remittances to the village and the family also ends up earning a lot of money. It is as much an economic issue as it is a social issue

-Kavita Srivastava, national president, PUCL

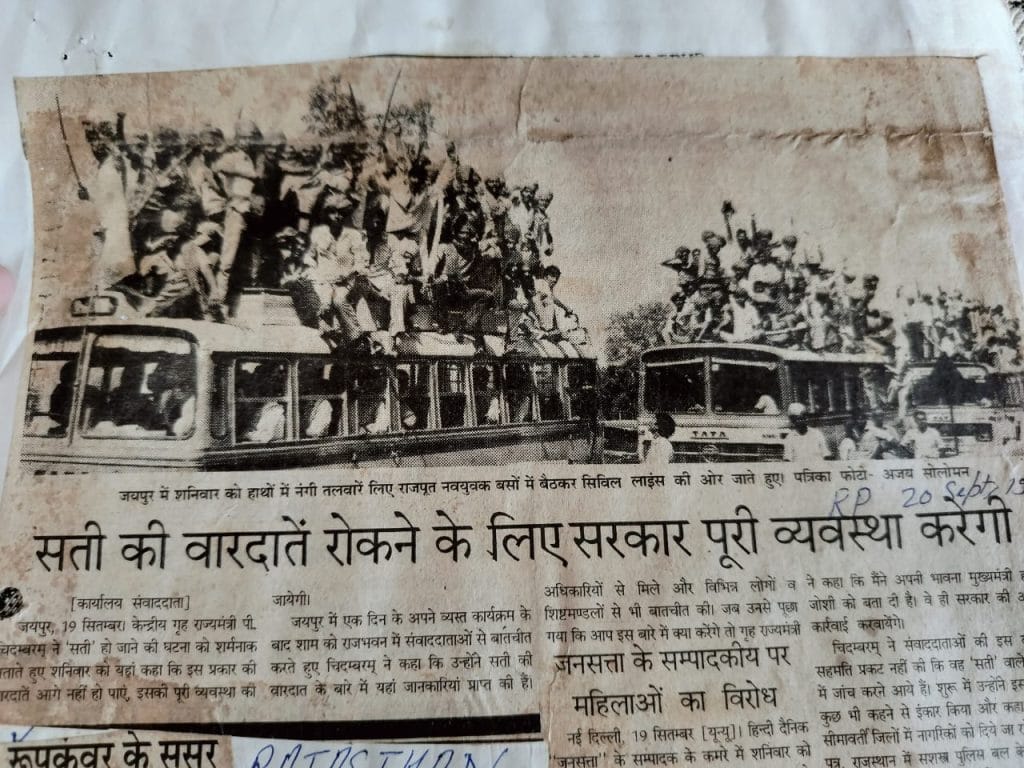

But for women’s groups who fought to end sati and its glorification, these acquittals are a betrayal and a bitter reminder of how deeply such beliefs run in Rajasthan’s soil. Roop Kanwar’s death was more than a fire in a village. It inflamed India. There were mass protests, then Chief Minister Haridev Joshi was compelled to resign, and a new 1987 law criminalised not only sati but its “glorification”.

Was Roop Kanwar a willing bride on the pyre, or was she drugged, dragged, and weighed down by coconuts and firewood? This, despite sati being banned in India since 1829. Protests, counter-protests, and even ‘festivals’ to celebrate sati followed. There seemed to be progress when, a year after her death, 45 people were arrested for glorifying sati as they attended an event, chanting “Roop Kanwar Sati ki jai.” But interest waned as the cases meandered in court. Many didn’t even take note that the case was coming undone over time bit by bit.

In 1996, 32 people, including her father-in-law and brothers-in-law, were acquitted of murder. The same went for the 45 charged in a special Sati Nivaran Court for glorifying her death. By October 2004, 25 were acquitted, and this month, the last eight were let go. Eight others had died in the interim, and four remain absconding.

The counsel representing the Rajasthan government, Rajneesh Kumar Sharma did not answer calls or respond to texts requesting comment. This report will be updated if a response is received.

Today, Jaipur’s Sati Nivaran Court has no pending file. It’s been settled—no one pushed her, burned her, or glorified her death.

Sati sacrifices can pave the way for temple-building, attracting thousands of visitors and greasing the local economy. Even husbands are elevated to demigod status.

Also Read: Heroic journalists who worked to keep Ajmer 1992 gangrape case alive—in public memory, courts

Deorala’s deity

That Sati isn’t a thing of the past is apparent in the run up to the full moon of the Bhadra month every year. That’s when hundreds of people from Rajasthan’s and neighbouring Gujarat descend upon Deorala in Neem ka Thana to observe the anniversary of Roop Kanwar’s sati.

Following dates of the Hindu moon-based calendar, busloads of these visitors head to her shrine, where they offer coconuts and red chunris. Many devotees arrive from Rajasthan’s Shekhawati and Marwar regions, while a group from Gujarat sets up camp at a local temple and organise bhandaras to feed people.

Last year, Roop Kanwar’s sister organised a special event at a local temple, inviting 12 Brahmin couples and hosting a community feast.

Roop Kanwar’s marital home, freshly painted yellow with bougainvillea leaf designs, stands out in a gully dotted with weathered havelis.

Her paralysed brother-in-law, Bhupinder Singh Shekhawat, maintains a vigil here, tending to the shrine inside dedicated to Roop and her husband Maal Singh. The rest of the family lives in Jaipur. Bhupinder has lost the ability to speak coherently, yet mumbles through a smile that a temple must be built where Roop Kanwar’s pyre was.

The police inferred that Roop Kanwar’s continued existence could have been undesirable to her in-laws

-‘1987 Trial by Fire’ report by Bombay Union of Journalists

Through a small window that’s always open, visitors can peer at the house shrine. Photos from her wedding show Roop in a pink lehenga beside her husband. A black-and-white portrait of Maal Singh is propped up too. But there are no photos of Roop Kanwar alone. Her deity status comes from how she died—and it has everything to do with being a wife.

Other homes in Deorala have made space for Roop Kanwar in their puja areas too. This ‘worship’ of her has its own iconography, crafted with help from local photo studios.

One doctored image shows her sitting calmly in the pyre, holding Maal Singh’s head in her lap—there’s no hint of the girl who reportedly screamed for help in her final moments.

Economics of sati

Sati temples aren’t just about belief—they bring in money and boost village fortunes. Sati itself has an economic aspect too.

Trial by Fire, a 1987 report on the Roop Kanwar case by the Bombay Union of Journalists, alludes to this.

Roop Kanwar, it notes, had brought 40 tolas of gold, Rs 30,000 in fixed deposits, a colour TV, a cooking range, and a refrigerator as dowry. And since Maal Singh fell ill and died just seven months into marriage, before an heir was born, she could have returned to her maternal home with these assets.

“The police inferred that Roop Kanwar’s continued existence could have been undesirable to her in-laws,” the report states.

Sati sacrifices can also pave the way for temple-building, attracting thousands of visitors and greasing the local economy. Even husbands are elevated to demigod status, motivating some families to pursue sati rites, according to Kavita Srivastava, national president, People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL).

“Satis are considered kuldevis by people of Rajasthan. A deity that must be worshipped and held in high regard. Some satis are said to leave directions before going to the pyre, like imposing restrictions on wearing glass bangles, which are followed strictly by people,” she said.

Entire cottage industries can spring up around these temples.

“Building sati temples is also monetarily beneficial for those involved in opening of the temple,” Srivastava added. “It brings development and remittances to the village and the family also ends up earning a lot of money. It is as much an economic issue as it is a social issue.”

They were yelling, ‘Ek do teen chaar, Roop Kanwar Sati ki jai jaikaar!’ and ‘Sati Mata ki jai!’ People randomly started these slogans. I didn’t. I was just 17.

-Shravan Singh, acquitted this month in the sati glorification case

Rajasthan’s Shekhawati region, including Sikar, Jhunjhunu, and Neem Ka Thana, is known as the ‘sati belt,’ with over 100 sati temples.

The grandest and oldest of the lot is the Rani Sati Mandir in Jhunjhunu, where the practice has long been glorified. Since independence, at least 28 widows have immolated within a 200-mile radius of this temple. A writ petition filed in 1996 against sati puja there is still pending in the Rajasthan High Court.

Several sati temples lie within 5-20 kilometres of Deorala too, including the Om Kanwar Sati Mata Temple, dedicated to a 16-year-old woman who died in 1980. This marble temple, managed by a trust, draws thousands each year. Also nearby is Devipura’s “living sati” temple—dedicated to a woman who was rescued by police but spent the rest of her days as a recluse. Near Roop Kanwar’s shrine, small, crumbling structures mark where other women met the same fate.

In keeping with the digital age, sati pratha has even gone online.

YouTubers from Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh offer virtual tours of sati temples, sometimes interviewing priests who glorify the practice—although they are careful to add disclaimers to avoid legal trouble.

In one video, a YouTuber provides a digital darshan of the Om Kanwar Sati Mata Temple.

“This video doesn’t glorify sati but shares the true miracles of Sati Mata,” he says. The priest in the video then claims Om Kanwar performed miracles from the pyre, like blinding a man who tried to stop her. “We don’t even know how the pyre was lit!” he says.

There are also bhajans dedicated to Roop Kanwar on YouTube. “Sati Roop Kanwar Mata, humein apni sharan dena,” sings Mukesh Bagda in one video. Another YouTuber describes the “privilege” of visiting her shrine. Some commenters warn him against glorifying sati. Others just write, “Jai Maa Sati.”

The Commission of Sati Act 1987 made abetment to sati punishable by life imprisonment or death. And sati glorification, under Section 5 of the law, could bring seven years’ jail and a fine of Rs 5,000.

Rajput pride, and not just in Rajasthan

Sati is still stitched into 21st-century Rajput pride. For many in the community, it’s a noble death, second only to jauhar, the mass self-immolation Rajput women undertook to save their ‘honour’. Yet, the tradition extends beyond the Rajputs; Jhunjhunu’s Rani Sati Temple is dedicated to an Agarwal bride. Dying as sati is seen as valorous for women, just as death on the battlefield is for men. Some even believe sati grants a woman the honour of being reborn as a Rajput man.

This belief persists across multiple states. Nearly four decades after Roop Kanwar’s death, temples dedicated to Sati Mata still draw worshippers in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

As recently as 2018, Rajput groups were not only glorifying jauhar, but threatening to walk into fire if Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat was released in theatres.

Even though the practice of sati seems unfathomable, the 21st century hasn’t been immune to it.

In 2002, a suspected sati case was reported in Tamoli Patna village in Madhya Pradesh’s Panna district, and three years later, another in Banda, Uttar Pradesh. In 2006, two more sati incidents surfaced in MP’s Bundelkhand region—one woman was saved in the nick of time, the other died.

Such incidents, though, faded quickly from public memory, with Roop Kanwar being immortalised as India’s last-known sati.

Also Read: Between the brothel and Brindavan—Bengal art shows twin faces of Hindu widows after sati ban

Old demand, fresh wound

It was an inflammable cauldron of faith, fire, and feminist anger in 1987. Rajput honour was at stake. So was the idea of a modern India. Feminist fortitude and Rajput faith locked horns on the streets of Jaipur.

As women poured onto the streets to denounce sati as glorified murder, Rajput leaders and their followers assembled at the Ramleela grounds, calling these protestors “bazaari aurtein” (loose women) and chanting “mandir wahin banega”—the temple will be built at Roop Kanwar’s ‘sati’ site.

They called us ‘baal kati, baah kati, jeeb kati’ aurtein (short-haired, short-sleeved, foul-mouthed women)

-Neerja Misra, social activist

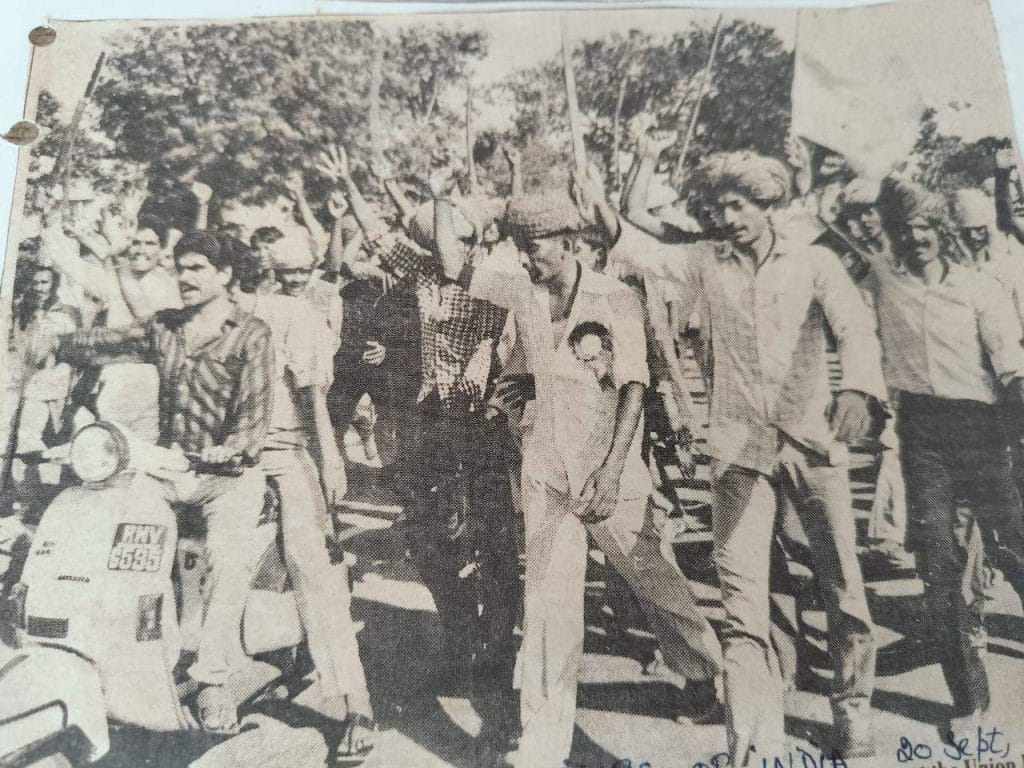

The freshly formed Sati Dharma Raksha Samiti—now just the Dharma Raksha Samiti—even organised a gathering of nearly 70,000 men, brandishing swords, in Jaipur. Their message was loud and clear: don’t interfere in our faith.

This demand for a temple never faded—and now, it’s gained new momentum after the acquittals. Roop Kanwar’s family members and many villagers in Deorala remain firm in their belief that her ‘strength’ deserves a mandir.

“If not a Sati mandir, then a Shakti mandir must be built,” said village priest Anand Singh Shekhawat.

For those who fought to end sati glorification, the acquittals in Roop Kanwar’s case are a serious setback.

“This (sati) outraged the world, and successive governments have been equally responsible for not holding anyone accountable. Glorification is something that perpetuates the ideology of sati,” said Kavita Srivastava of the PUCL.

A leader in the anti-sati movement of the 1980s, she has since kept close watch on the case, filing multiple petitions and documenting the court proceedings.

“Acquittals will embed the ideology deeper into the minds of people,” Srivastava added. “We have to nip it in the bud.”

The fire

Roop Kanwar’s brother Gopal Singh Rathore sits in a humble, grey-walled office in the by-lanes of Jaipur’s Transport Nagar, with a fat file on his table. Inside it are newspaper clippings, growing brown and brittle with time. It is his archive documenting the aftermath of his sister’s death.

On 5 September 1987, Rathore awoke to the news of his sister’s “sacrifice”. He recalls it as a moment of pride.

“Even if you touch a hot cauldron while cooking, it hurts so much. She sat in a funeral pyre,” he said admiringly.

Rathore, eight years older than Roop Kanwar, claimed she was always deeply devout.

“She used to go to sati temples even as a child,” he insisted.

By the time Rathore arrived in Deorala, the pyre of Maal Singh and Roop Kanwar had cooled to smouldering ashes.

“When I reached, women were taking parikrama of the funeral pyre. We were told she (Roop) gave her sati willingly. And I am very proud of her,” he said.

In Deorala, villagers and Kanwar’s family members hold on firmly to this story—that Roop Kanwar chose her fiery end after her husband died of gastroenteritis in a Jaipur hospital on 3 September.

They say she stepped out in full bridal regalia, the solah shringaar, on the morning of 4 September, leading a procession to her husband’s pyre. No one forced her, they claim, but clearly no one stopped her either. According to local lore, as she climbed the pyre, she told her father-in-law her only regret was that she never got to serve him. She’s portrayed as the perfect, divine bride.

There were no eyewitness accounts that the prosecution could produce to prove my client or other co-accused were guilty

Bhanwar Singh Rajpura, a defence counsel in the glorification case

But independent fact-finding reports paint a different picture. For the Trial by Fire report, a three-member team recorded testimonies by villagers. Some claimed that Roop Kanwar—suspecting she was about to be forced into sati—tried to flee, hiding behind a dhaani (barn). But then, they say, she was found, dragged back, and pushed into the pyre.

“She is said to have screamed and struggled to get out when the pyre was lit, but Rajput youths with swords surrounding her made her escape impossible,” reads the report.

Eyewitnesses also described seeing Roop stumbling and dazed on the way to the cremation ground. The police, too, suspected that Maal Singh’s doctor had injected her with drugs.

“Eyewitnesses questioned by the police said they heard her shout ‘bachao’, she cried for help and struggled to get out but the coconuts and the heavy logs of firewood buried her,” says the report.

It was Kanwar’s 15-year-old brother-in-law, Pushpendra Singh, who lit the pyre as hundreds watched, it adds, unequivocally describing her death as murder.

“It is common in Sati cases that villagers push a minor to light the pyre, so the quantum of punishment, if found guilty, is less severe,” Kavita Srivastava of PUCL said.

The prosecution couldn’t convince the court that Roop Kanwar had been murdered—or even that she had been immolated at all. No eyewitnesses to the sati were brought forward.

Battle on the streets

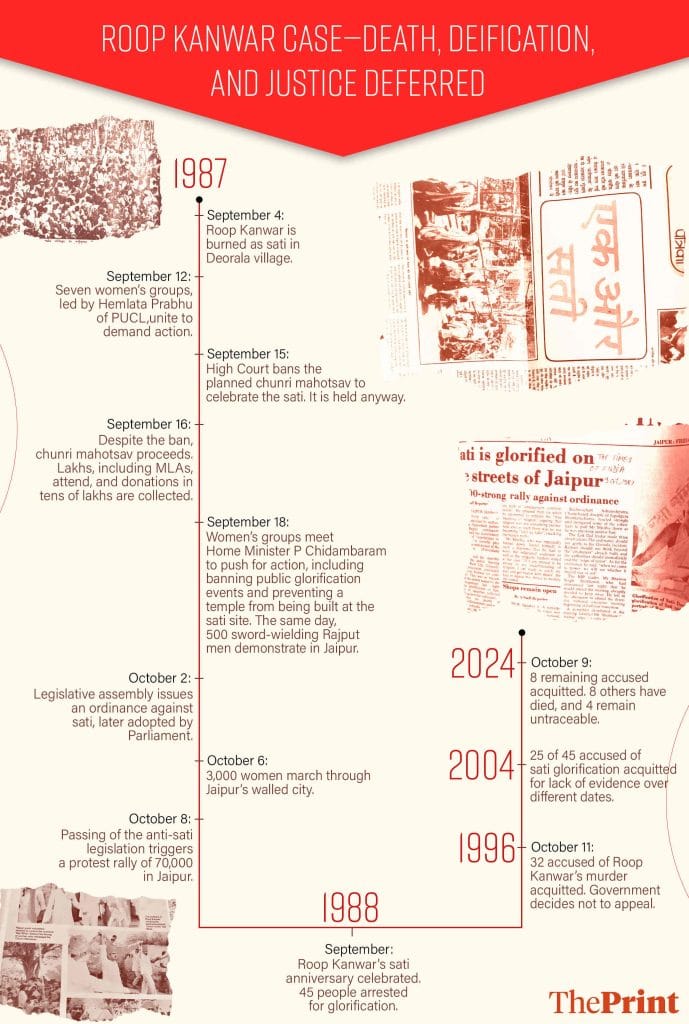

In the autumn of 1987, Neerja Misra, a lecturer at Kanoria College in Jaipur, was strolling near Bapu Bazaar when a young man handed her a poster. It announced a chunri mahotsav— a ‘festival’ centred around the ritual of placing a red scarf over a pyre. This one was to be held on the 13th day of mourning for Maal Singh and his bride Roop Kanwar.

The poster immediately set off alarm bells for Misra, who was a part of the women’s groups pushing the government to act against the glorification of sati. Holding it, she was repulsed.

“I took that poster to Miss (Hemlata) Prabhu, who was the general secretary of PUCL at that time. I told her Roop Kanwar’s sati had happened, but now she will be celebrated and immortalised as Sati Mata, and they’d make a temple there,” she said. “The women’s groups were prepared to not let that happen.”

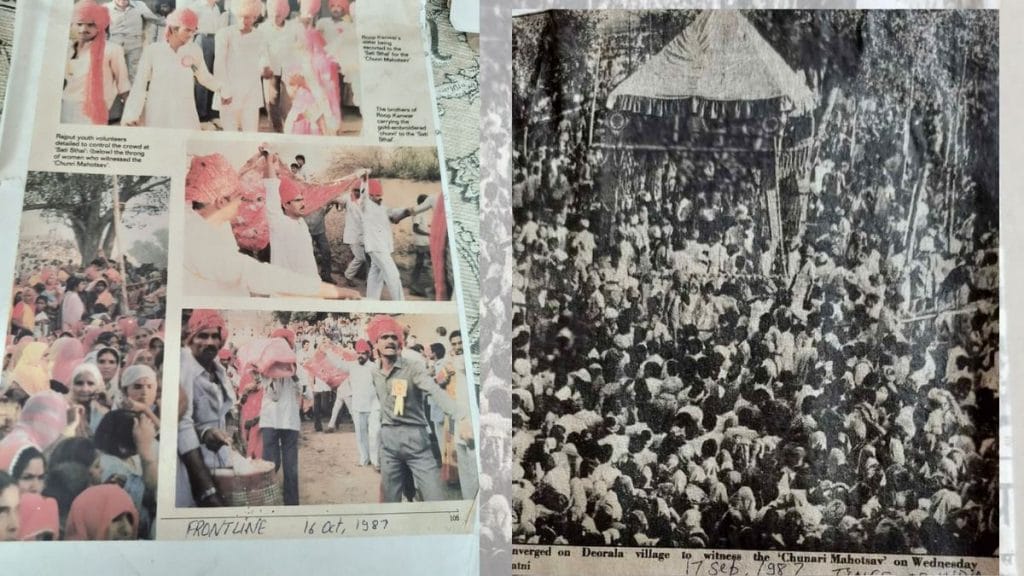

On 14 September, 300 women from 11 different organisations led a morcha to the secretariat, headed by PUCL’s Hemlata Prabhu. They demanded a stop to the glorification of sati and murder charges against those involved in the “sacrifice.”

Women’s groups, students, doctors, and lawyers marched silently through Jaipur’s streets, holding placards that read: “Sawaal hai naari ki pehchaan ka, sawaal hai naari ke samman ka” (It is about women’s identity and respect). They sought meetings with the Chief Minister and Home Minister, but were told no minister was available. Ultimately, they handed over a memorandum to the Chief Minister’s secretary.

People’s beliefs are attached to this place (where Roop Kanwar died). If not a Sati Mandir then a Shakti Mandir must be built

-Anand Singh Shekhawat, Deorala priest

Rajput leaders then hit back with their own campaign, mocking the women as “Western ideologues” and slandering them as club-goers who lived in AC houses.

But the activists pressed on. A writ petition was filed in the Rajasthan High Court against the planned chunri mahotsav set for 16 September in Deorala. Though they secured an order banning any public gatherings glorifying sati, over 2 lakh people attended the event. MLAs from different parties also attended, and the police did not impose Section 144 to prevent the event.

The ceremony itself just saw Roop Kanwar’s brothers place money and a dupatta over the pyre. But the turnout was grand. ‘Devotees’ poured in from all over the state and the event reportedly generated around Rs 70 lakh, as visitors purchased offerings and other items.

Shortly after the event, however, police arrested several members of Roop Kanwar’s marital family. This led to nationwide protests from Rajput groups, with thousands flooding Jaipur’s streets, chanting “Roop Kanwar Sati ki Jai!” and forming the Sati Dharma Raksha Samiti.

They also unleashed invectives on women protestors. An activist who argued that Sati was not suicide—since someone else lights the pyre—was surrounded, abused, and defamed, reports Trial by Fire. Activists also said they received many threatening calls and insults.

“They called us ‘baal kati, baah kati, jeeb kati’ aurtein,” (short-haired, short-sleeved, foul-mouthed women),” Misra recalled with a snort.

Politicians of various hues also jumped into the fray, possibly eyeing the Rajput and Hindu vote-bank.

“How could these women know about pavitrata (piousness) or the desire to commit Sati?” BJP leader Om Prakash Gupta reportedly said at one public meeting.

But the outcry from women’s groups and activists—not just in Rajasthan but in Delhi, Kolkata, and elsewhere— tipped the scales. The Rajasthan government quickly passed an anti-sati ordinance, which soon became a central law—the Commission of Sati Act, 1987. It made abetment to sati punishable by life imprisonment or death. And sati glorification, under Section 5 of the law, could bring seven years’ jail and a fine of Rs 5,000.

But in Roop Kanwar’s case, no one faced the full force of the law.

“No matter how hard you fight, sometimes it doesn’t give results,” said Renuka Pamecha, a retired professor of Political Science from Jaipur. “The convictions didn’t happen. Bolo, kya karein?”

The murder trial

When several people from Deorala were arrested for their role in Roop Kanwar’s death, there were calls to boycott Diwali if they weren’t released. Despite the pressure, the murder case went ahead in the court of the Neem Ka Thana additional district judge, with 32 people on trial.

This case was the first to go up in smoke.

The First Information Report was based on the complaint of Chandra Ram Jathi, a police constable who became the main prosecution witness. According to the FIR, 125 people were present around the pyre when the police reached the village.

But the prosecution couldn’t convince the court that Roop Kanwar had been murdered—or even that she had been immolated at all. No eyewitnesses to the sati were brought forward.

Crucial evidence, like the Trial by Fire report, was never presented. The prosecution also didn’t pursue the eyewitness accounts collected by the journalists. After years of delays, on 11 October 1996, the court acquitted all the accused, citing a lack of evidence.

“It is not proved from the evidence of any witness of the prosecution that Shrimati Roop Kanwar had died due to burning in the pyre or she was forcibly burnt by Pushpendra Singh or somebody else killed her,” read a translated excerpt of the judgment, as reported by The Lawyers Collective in 1997.

The judgement also noted that the prosecution’s witnesses had based their testimonies on hearsay rather than firsthand accounts.

“The prosecution had not examined those persons who have witnessed the commission of the alleged incident,” it added.

ThePrint could not access the full 1996 judgment, which remains unavailable online or at the Neem ka Thana court.

The glorification case

A year after Roop Kanwar’s death, a truck rolled through Deorala village, a banner on its side reading, “Jai Shree Maha Sati Roop Kanwar ki Jai”. Dozens of men rode on top, shouting slogans and praising her “sacrifice”.

This open show of devotion to a banned practice didn’t go unnoticed. Police quickly charged all 45 people on board with glorifying sati. Among them were some high-profile names—Rajendra Rathore of the BJP and Congress’ Pratap Singh Khachariyawas.

The prosecution’s evidence included the truck itself, a manipulated photograph of Roop Kanwar seated calmly in the flames, and statements from key witnesses.

The trial, held in a special court, unfolded in two batches due to the large number of accused—some of whom had initially absconded and surrendered later. And each time it was like a sequel to the earlier murder case—witnesses turned hostile, and evidence seemed to evaporate.

In 2004, 25 of the accused, including the politicians, were acquitted. This month, eight who later surrendered were acquitted, while four remain absconding.

The witnesses in 2004 included 14 policemen— all claimed they couldn’t identify any of the accused they themselves had charged.

Sub-inspector Bajrang Lal told the court he never saw the truck full of people. Another officer, Rakeshprakash Sharma, said that after 17 years, he couldn’t remember the accused. Other police witnesses acknowledged that pro-sati sloganeering happened but couldn’t confirm if the accused were involved. One RPF officer, who had a video camera back then, testified that he captured no footage of the event.

Also Read: 2 men raped Bhanwari Devi for trying to stop 1992 child marriage. ‘I curse her daily,’ says bride

A free man

After nearly 40 years, Shravan Singh can finally breathe freely. Earlier this month, he was acquitted of glorifying Roop Kanwar’s sati—an accusation, he says, that ruined his life when he was just 17.

Today, he is a frail man living with his wife in a one-room house in Rathoron ki Dhaani, a prosperous Rajput village. Farmers, contractors, and liquor shop owners have built sprawling mansions here, but Singh hasn’t shared in the village’s fortune.

“I wanted to be in the army or the Border Security Force. I had cleared all my exams but would always fail police verification. I could have led a comfortable life for my children, but couldn’t,” he told ThePrint at his house.

Singh insists he was simply at the wrong place at the wrong time. In September 1988, he says he was just along for the ride when friends and relatives hyped up the sati mela at Deorala. He put on his best clothes and boarded a bus for the festival.

“They were yelling, ‘Ek do teen chaar, Roop Kanwar Sati ki jai jaikaar!’ and ‘Sati Mata ki jai!’” he said. “People randomly started these slogans. I didn’t. I was just 17,” he said

But Singh was charged along with 44 others with glorifying sati under Section 5 of anti-sati law.

Singh lived like a fugitive for years, ignoring court warrants until he surrendered in 2004, after 25 co-accused were acquitted. He claimed he missed the warrants because he was away working in Delhi or Gujarat.

“My client (Shravan Singh) had been fighting this case for 36 years because earlier he couldn’t respond to court warrants. It was a logistical nightmare for courts as well to have 45 accused in the court at the same time,” Bhanwar Singh Rajpura, one of the eight defence counsels in the glorification case, told ThePrint. “There were no eyewitness accounts that the prosecution could produce to prove my client or other co-accused were guilty.”

With the case now closed, the accused, villagers, and Roop Kanwar’s family still stop short of condemning the practice of sati. Yet they dismiss the idea that it could happen again—some with regret.

Bhagwan Singh Rathore, a member of the Karni Sena, echoed a sentiment reminiscent of the Rajputs’ rhetoric in 1987.

“I don’t think sati can ever happen again,” he said with a scowl. “Today’s women are not like women of the past. They’d never walk into a burning pyre out of love for their husband.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Sati mata ki jai

Glorification of Sati in 21st century! And there are stiil people in our country who argue practitce of sati never happened in our history.