A woman wearing a white muslin sari with a black border posing in the pleasure houses of 19th-century Bengal paintings carried twin identities. She was a widow working as courtesan, living between two worlds – one dead and the other yet to be born. Sati had been banned and widowed women were not being flung into the flames, but families continued to reject them.

Many survived by taking up sex work. And the brothels comprised of predominantly Hindu women. They had gained the gift of life because of the social reforms sweeping through colonial Bengal but were still not assured of dignity.

“The 19th-century art from Calcutta documented many small and large changes that were occurring under the colonial regime: gods and monsters wear Oxford shoes, women beginning to wear blouses, the end of Persian as an official language,” says Shatadeep Maitra, Project Manager of Exhibitions at DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery). “Like everything else, the end of satipratha and its social consequences became mixed with popular imagery. Having limited or no education, many women whose husbands had died had to rely on sex work for survival.”

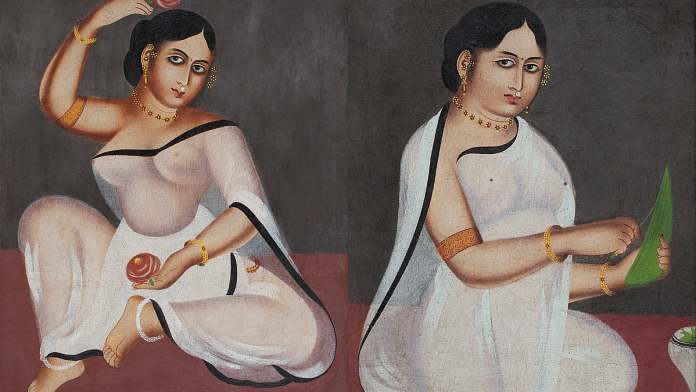

In a curated walkthrough of the colonial watercolour Kalighat pat artworks, early Bengal oil paintings and prints called ‘Sati & Sundari’ at the DAG, about a dozen images served as a reliable narrator of women’s history of the times. These images are part of an ongoing exhibition called The Babu & the Bazaar.

“The Sundari images in early Bengal art served as pin-ups for gentrified audiences but had a dark history,” says the DAG brochure.

The bejewelled women in white were portrayed playing the violin or tabla, preparing paan, and adorning their hair with roses – paan Sundari and gulab Sundari. They wore ghungroos (anklets) on the right foot – much like the Mughal tawaifs. They were widows and courtesans. And embedded in their hybrid identity was the story of great social disruption.

This Sundari iconography formed a complex world of popular erotica of that era and was commissioned by wealthy individuals of Kolkata, says Maitra. These oil paintings and the prints wouldn’t be displayed in temples or homes but more likely in the men’s pleasure houses. Many of them featured private moments of the women.

It is like “we are peeping into the sanctum santorum of a woman’s home. These images are pin-up, they are also voyeuristic, given how the women are always shown wearing translucent saris.”

Also read: North Indian artisans carry a photo of this textile historian — she helped revive…

Between the brothel and Brindavan

The 19th-century churn in Bengal was a heady era of changes in a society still largely unprepared for and unwilling to allow women’s autonomous lives. Reformers Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar bookended some of the century’s most transformative changes from ending sati, and child marriage to a move to end polygamy, promoting widow remarriage and inheritance rights for women.

But traditional, dominant caste families were still not ready to accept these women. Famine and poverty-stricken women, abducted and raped women, and, most significantly, widows from Kulin Brahmin families who were rejected as liabilities ‘formed the first generation of prostitutes in the colonial world of market economy of 19th century Bengal’, wrote Sumanta Banerjee in a 1993 article titled The ‘Beshya’ and the ‘Babu’: Prostitute and Her Clientele in 19th Century Bengal in Economic & Political Weekly.

“In Bengal, the prostitute class seems to be chiefly recruited from the ranks of Hindu widows,” wrote British civil servant Alexander Mackenzie in a letter to HL Dampier, the Official Secretary to the Government of India in 1892.

A survey report in the 1850s said there were a total of 12,000 sex workers in Kolkata, of which 10,000 were Hindu widows and daughters of Kulin Brahmins, according to author Usha Chakraborty’s book Condition of Bengali Women around the 2nd Half of the 19th Century (page 9). Muslims allowed widow remarriages, something the Hindus opposed for long. The Dharma Sabha wrote a petition with scores of signatures countering Vidyasagar’s efforts to enable widow remarriages. It was finally legalised in 1856.

But society took a much longer time to catch up with the new legal reforms.

This dysfunction with tradition and encounter with modernity, Tapati Guha Thakurta wrote in a 1991 article titled Women as ‘Calendar Art’ Icons: Emergence of Pictorial Stereotype in Colonial India, produced “a sharp edge in all cultural expressions” of that era.

For many, one road led to the brothel. The other went to Brindavan.

Women in white saris with black borders are also seen cradling and playing with baby Krishna in many watercolour paintings. To this day, Brindavan is considered a religious refuge for widowed women who spend the rest of their lives in Krishna devotion.

BR Ambedkar wrote in his Columbia University thesis in 1916 about sati, forced widowhood, endogamy of caste, and what he called the problem of ‘surplus women’ in Hindu society. “Sati, enforced widowhood, and girl marriage are customs that were primarily intended to solve the problem of the surplus man and surplus woman in a caste and to maintain its endogamy…Burning the widow eliminates all the three evils that a surplus woman is fraught with. Being dead and gone, she creates no problem of remarriage either inside or outside the caste.”

The sati ban made it into a bigger problem.

Also read: Delhi’s Partition Museum remembers pain of separation—through artefacts, images, personal items

Missing in history books

Social change doesn’t come in one fell swoop for women. It is messy and comes in staggered waves. And yet, women’s historiography is primarily made up of points of quantum leap reforms. Not enough is said about the price of freedom some women paid because of unintended fallouts of change. How the lives of women got impacted in the immediate aftermath of the Sati ban is one such information gap.

The Sundari stereotype does not exist in history books, says Maitra.

In the United States, World War II brought around five million women into the workspace of defence manufacturing and factories because men were on the battlefield. The iconic artworks called ‘We Can Do It’ by American graphic artist J. Howard Miller and ‘Rosie the Rivetter’ by Norman Rockwell came out in 1943 and marked a seminal shift in the history of women’s work.

But this liberating encounter of women with the factory floor was short-lived. When the war ended, the men returned home and took back these jobs. It wasn’t easy for the women to return to the confines of their kitchens. A lot of writings and letters by women around that time of difficult transition – both about the factories and their exits — are preserved in the State historical archives.

Indian scholarship is almost non-existent on similar stories of liminal spaces between social reform and pushback.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)