New Delhi: When Rajiv Riyaz Pratapgarhi spoke at Dalit Chetna, the Sahitya Akademi event marking Ambedkar Jayanti, the audience came alive. They clapped and cheered as the Delhi secretary of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen turned a mundane celebration into a mushaira, inserting shayari into a basic biography of BR Ambedkar and a primer on Dalit representation. Barely a few weeks earlier, just after the Akademi’s Festival of Letters, venerable Malayali author C Radhakrishnan quit the Sahitya Akademi council citing political interference.

But in interviews with writers like Namita Gokhale and Harish Trivedi, ThePrint found that the Sahitya Akademi is one of the last bastions of autonomy, surrounded by compromised institutions.

“We are all singing the same song about social justice and social equality. We’re all human beings, not untouchables,” said one speaker at Dalit Chetna.

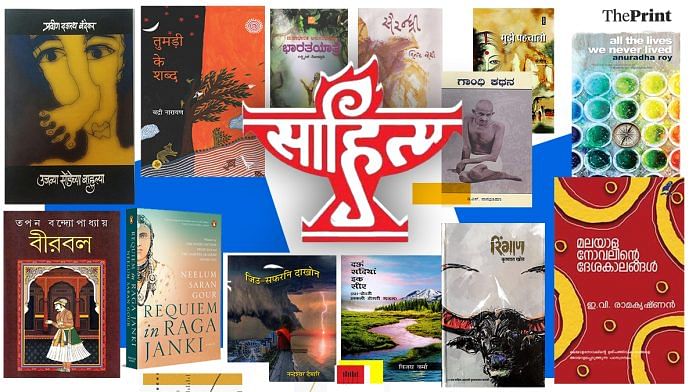

The 70-year-old literary institute is in the middle of a churn amid accusations that its threadbare walls are turning saffron. But Pratapgarhi’s debut speech at the Akademi stands in contrast to that. And the Sahitya Akademi is poised to shed its Nehruvian-era skin and propel itself forward—it’s looking to expand, and then transform. According to the administration, a Sahitya Akademi book is published every 18 hours.

It’s integrating Kashmir into the collective literary consciousness of the country, promoting the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, taking festivals to different parts of the country, and recognising the diaspora as a force to be reckoned with.

The scale of its festivals is increasing—last year alone, it held more than 600 programmes across the country with hundreds of writers in dozens of languages partaking in session after session. It’s also wading into fresh territory. The literature of the marginalised is taking centre stage, with Dalit, LGBTQIA+, and Adivasi writers gaining access to a coveted space that not too long ago, was far out of reach.

Literature is no longer highfalutin, and nor is the Akademi.

“Not only has the Sahitya Akademi sustained, it’s improved. Moreover, in the last few years, the quality of seminars has improved. The funding has risen, though that’s happened with all other institutes. We’re a more affluent country,” says writer and translator Harish Trivedi, who was previously part of the Akademi’s Hindi advisory board.

In 2016, the Akademi introduced the first Gramalok Prakash programme, in an attempt to make literature a lifestyle in the remotest of villages, including in Kargil. Set up to frame a corpus of literature that is distinctly ‘Indian’ by paying homage to 24 languages, including English and Urdu, which aren’t enshrined in the Constitution, it’s now about making literature easy and accessible.

Last month, the Sahitya Akademi astutely marketed its Sahiyotsav—an annual Festival of Letters at Delhi’s Rabindra Bhavan—as the world’s largest festival with 200 authors and 175 languages. Writers from the LGBTQIA+ community, the Northeast and the Adivasi communities were at the helm. Discussions traversed a range of domains—tech, the Bhakti movement, and transgender narratives.

Not only has the Sahitya Akademi sustained, it’s improved. Moreover, in the last few years, the quality of seminars has improved.

– Harish Trivedi, writer and translator

There were hundreds of writers, but only two mattered—Radhakrishnan, who has won dozens of awards, and Arjun Ram Meghwal, Minister of State for Culture, who the Akademi quickly clarified in a statement, was also a ‘writer’. But for writers like Radhakrishan, the minister’s presence is representative of a larger malaise: the ruling party’s interference in the affairs of the country’s cultural institutions.

K Sreenivasa Rao, Sahitya Akademi’s secretary since 2013, dismisses such allegations—the Sahitya Akademi’s interests lie not in politics, but in introducing itself to a new generation of Indian readers. It’s all about expanding its footprint.

“Our existence has changed. There’s more visibility, more outreach. Earlier, we were only thinking about elite writers,” says Rao.

As a result, their sales have increased “tremendously”. Prior to Rao’s tenure, the Akademi’s turnover was about Rs 2 crore, as of this year, it’s increased to Rs 15 crore. There are Sahitya Akademi bookstores in three metro stations in Delhi, so fatigued commuters, many of whom are young professionals unacquainted with the Akademi, can read on the go.

As an institute, we’re very balanced, but it’s about Indian literature for us. We cannot separate being Indian from our culture, our religion, our epics

– K Sreenivasa Rao, secretary, Sahitya Akademi

There’s a corner dedicated to children in the Sahitya Akademi library in Delhi, once a mainstay for sombre scholars and writers. It’s all part of a project to revive the masses and to make books fashionable in the age of doom scrolling.

“There’s nothing like this in the government sector,” declares Rao.

Since 2021, every single seminar and symposium has been a celebration of Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav—literary validation of India’s cataclysmic success on the global and domestic stage. Whether it’s a book launch on modern Iranian poetry or a seminar on the centenary year of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, it’s all in service to the country.

“As an institute, we’re very balanced, but it’s about Indian literature for us. We cannot separate being Indian from our culture, our religion, our epics,” says Rao.

Also read: India’s cultural renaissance has begun. IGNCA leading it with Vastu, Vedas, and ‘new’ history

‘Every book is one’

In its new avatar, where literature and culture are now inextricable, the Ramayana and Mahabharata now occupy positions of prestige in the Akademi. Rao’s tenure has ensured two sessions on the “popular consciousness of the Ramayana”, as well as international conferences on the epics to assess their global appeal. Japanese translator of Indian myths and texts, Hiroyuki Sato, called the Ramayana “a symbol of values and lifestyle” at the Festival of Letters last month.

“The government is fully supportive of promoting Indian culture. That is the need of the hour. We are the role models of the world. We’ve given so much, and that’s what the government is able to establish,” says Rao, adding that literary activities are conducted in a “dignified manner” and no one community or religion is favoured. But he’s quick to add that the Akademi is an institute under the Ministry of Culture. It’s fully funded by the government. “We present our annual report every year in Parliament.”

The Akademi’s founding principle is ‘oneness,’ as it centralises disparate languages. Every year, 24 awards are given—one for each language. That’s when the machinery kicks in. These winning books are then translated into the 23 other languages, by translators spread across the country.

“Sahitya Akademi, in effect, is India’s largest publishing house,” declares Sahitya Akademi President Madhav Kaushik. “Every book is one, though it has 24 versions.”

This governing ethos ties in neatly with Ek Bharat Ek Shrestha, a government initiative to “promote mutual understanding between people of different states”. There’s no better example than Rao himself.

“We are all human beings. I’m from Andhra Pradesh, I’ve settled in Delhi, and I’m speaking in Hindi. Today, we have Tamil literature coming to Kashmir. That itself is going to lead to a developed India,” Rao says.

Last year, the Ministry of Culture and Sahitya Akademi held a series of three lectures in Chennai, Pune, and Srinagar as part of a festival to invite and emphasise the integration of Kashmiri culture with the rest of India. The conversations were then converted into a book published by the Akademi, in the synopsis of which the scheme is extolled as one of Prime Minister Modi’s many virtues.

Sahitya Akademi, in effect, is India’s largest publishing house. Every book is one, though it has 24 versions

– Madhav Kaushik, Sahitya Akademi President

“Without understanding Kashmir, we cannot understand the age-old dictum of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the world is one family—the axiom that shaped last year’s G20 summit,” reads the synopsis.

In 1976, S Gopal won the Sahitya Akademi award in English for his biography of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was also the institution’s first Chairperson. According to a clarification issued by the Ministry of Education, Nehru was invited to be chairperson, not because of his governmental position, but because he was a “man of letters”.

India’s literary might

In its previous age, the Akademi’s sole claim to fame was its translations. Now, the books are being buoyed by a litany of events and seminars. The Festival of Letters is one of many—part of the institute’s quest to be both Indian and international. Shimla and Bhopal have both played host to Unmesha, an ‘international festival’—a programme that flexes India’s literary might. “We want to showcase our talent on international platforms too,” says Rao.

Much like the Festival of Letters, Unmesha’s 2022 edition was accompanied by a grand suffix. It was promoted as the country’s largest literary festival, even if it didn’t usurp the entire continent. There were writers from 15 countries and a thousand books on the Independence movement.

A lecture by Geetanjali Shree, a bharatanatyam performance by Sonal Mansingh, and sessions by Gulzar and Vishal Bharadwaj—all stops were pulled out in Shimla two years ago. Gulzar and Bharadwaj participated in a session on literature and culture, while Shree discussed women writing in Indian languages. Meghwal, the minister, was present at Unmesha as well. Simultaneously, buried beneath the big names, were also programmes held to promote local dialects, and those that featured queer writers.

The Akademi is also tapping into the now widely influential Indian diaspora. Since 2020, International Diaspora Day has been celebrated through a number of conferences, a first for the Akademi.

There weren’t that many literary activities taking place earlier, though our predecessors were great people. Festivals were only within the Ravindra Bhawan [the building in which the Akademi is housed]

– K Sreenivasa Rao, secretary, Sahitya Akademi

There are Telugu writers in Canada, Tamil writers in Singapore and Malaysia, and the shift online gave a gateway to all. They’re also keeping track of foreign writers in Hindi, Rao says, mentioning an Uzbek professor who specialises in Hindi.

Last year, according to the Akademi’s annual report, a total of 690 programmes were held across the country, with 124 book fairs, 29 seminars, and 13 centenary-year symposiums.

“There weren’t that many literary activities taking place earlier, though our predecessors were great people. Festivals were only within the Ravindra Bhawan [the building in which the Akademi is housed],” says Rao. The slowness, the doggedness typical of government institutions is now replaced with slick speed.

Also read: ‘India’s only nationalist historian’ — ASI’s go-to curator was a card-carrying communist

Methods of protest

The reported ‘fielding’ of candidates that belong to one party in internal elections, the lack of resistance, and the Akademi’s descent into mediocrity led to Radhakrishnan’s exit. In the past, attempts by the culture ministry to “browbeat decisions of the executive council” were met with stiff resistance.

But the executive council elections held in March 2023 changed this. “Nominations to the general council from universities were also attempted to be made partisan in states controlled by a party,” says Radhakrishnan.

His detractors accused him of being politically motivated. “But my colleagues in the Akademi and my readers in the country know well that I have never been partisan in my 85 years of life,” he says.

The last time the Akademi made waves of such intensity was in 2015, when 39 of the country’s biggest literary names returned their Sahitya Akademi awards, in protest against the “assault” on liberal values, the erosion of secularism and the institution’s stony silence. It’s come to be known as ‘award-waapsi’—an era-defining moment in the institute’s history.

Even those authors who have returned the awards, they participate in our programmes. It was a minor impulsive incident that had no effect on the community

– Madhav Kaushik, Sahitya Akademi President

Almost a decade later, the process is still underway and the methods of protest continue to be similar. “I did it [resign] to highlight the imminent need for attention to save the independence of the last democratic cultural institution in the country,” says Radhakrishnan.

There are two camps—writers convinced that the Akademi has been saffronised, and those who see it as a last remaining frontier. But Kaushik, elected last year as the custodian of India’s writers, is unconcerned by the furore. “Even those authors who have returned the awards, they participate in our programmes. It was a minor impulsive incident that had no effect on the community,” he says, almost nonchalantly.

Even so, the tussle persists. “There has always been a struggle between the state and the Akademi, but the Akademi did not succumb to attempts to eat into its autonomy,” says Congress-era cultural czar and acclaimed Hindi writer Ashok Vajpeyi, one of the first to return his award.

A Punjabi book, published by the Akademi which had a “critical description” of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her actions and views drew controversy. When the matter was raised in Parliament, an MP said the Akademi was an autonomous body, and its decisions are neither influenced by nor interfered with by the government. This, according to Vajpeyi, is no longer possible.

Also read: Drive out Marxists, focus on Savarkar, Hindu kingdoms — ICHR’s walls now saffron. Literally

Temptation to interfere

In the early 1990s, when Narasimha Rao was Prime Minister, and Arjun Singh was Human Resources Department Minister, there were reports that the latter was in favour of replacing the Sahitya Akademi with a new body.

The Akademi then sent a delegation of about 40 writers to go and meet the PM at his house, and the threat was averted, recalls Trivedi. He was one of them. And it’s not the only instance of successive governments in the past feeling tempted to interfere.

As reported earlier by ThePrint, a number of India’s cultural institutions have come under the scanner for their shrinking autonomy and fluid identities following the BJP coming to power in the centre. For some writers, Sahitya Akademi is the last remaining frontier.

In certain ways, it’s been spared so far by virtue of its internal democratic structure—a collegium and a “free and fair election”, understood as such since even the most renowned writers have lost—including Vajpeyi.

“The Sahitya Akademi isn’t like the other Akademies. There, the government nominates the Chairpersons. But in the Sahitya Akademi, writers from all over the country elect a president every five years,” says Trivedi. “Writers of all kinds of opinions and inclinations have stood for the elections, and all kinds of writers have won—and lost.”

It’s a bastion, according to Namita Gokhale, who won the Sahitya Akademi award in 2021. “It’s a valuable cultural institution, independent and committed to literary diversity. And most importantly, what needs to be preserved is its heritage and legacy. Look at the books they have published, the writers they have nourished,” she says. “There’s no gatekeeping, it’s a gateway for young writers.”

Its history has been shaped by the luminaries who have walked its halls and overseen its workings.

The Sahitya Akademi isn’t like the other Akademies. There, the government nominates the Chairpersons. But in the Sahitya Akademi, writers from all over the country elect a president every five years. Writers of all kinds of opinions and inclinations have stood for the elections, and all kinds of writers have won—and lost.

– Harish Trivedi, writer and translator

From Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya to Uma Shankar Joshi, literary legends and Jnanpith Award winners have been presidents. Kaushik, on the other hand, has far fewer achievements to his name. Its ‘inclusivity’ and the dwindling number of illustrious writers also point to a fresh trend—it’s been infused with mediocrity.

“There has been a steady decline as evidenced by the stature of office bearers, the content of programmes, and the actual effect of the Akademi on India’s creative literary scene,” says Radhakrishnan. The ‘opening-up’ of the institute comes with fading relevancy.

“The vast majority [of the Akademi] consists of mediocre and popular writers. In the general council [which has about 100 people], there are probably not more than 10 people who matter in their respective languages and writers,” says Vajpeyi.

Siyaram Sharma, Sri Tulsi Raman, and Maha Singh Poonia, as well as other present members of the Hindi advisory boards, do not boast of Vajpeyi’s literary laurels.

What we have got, instead, says Vajpeyi, is an “organised spectacle” in the name of culture. “The contradiction is that where there’s supposed to be a national institute to promote excellence, that institute is also supposed to provide excellence,” he says.

The reset, however, has already taken place. And the chances of another are slim. “The time has come. It should be closed down. The Akademi has outlived its importance and its relevance. It’s entrenched in mediocrity,” he says. There are no two ways about it.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)