New Delhi: In its 30th year, India’s apex human rights watchdog is facing the risk of losing its top-level ranking from a United Nations-affiliated body for the second time since 2016. Today, the National Human Rights Commission is being called out for its silence over human rights violations in India, and is facing a credibility crisis — nationally and internationally.

Over the years, the NHRC has devolved into a “toothless tiger”— a term used in 2016 by its own chairperson at the time, former Chief Justice of India HL Dattu, as well as the Supreme Court in 2017. Allegations of political interference in appointments, failure to act on human rights violations, staff shortage, lack of diversity, poor cooperation with civil society, and non-implementation of its reports have all bedevilled the institution.

Several of these factors led to the commission’s accreditation being deferred earlier this year by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), a UN-affiliated body based in Geneva.

Fifty per cent of the complaints in the commission are by women or concerning women and children… but there is no woman representation on the NHRC

-Jyotika Kalra, former member of the NHRC

Only two other countries out of the 13 reviewed also faced deferrals—Costa Rica and Northern Ireland. This, though, is not the first time that the NHRC’s accreditation has been deferred—it also happened in 2016.

When the NHRC was set up in October 1993, against the backdrop of global criticism and scrutiny of human rights violations in India, there was excitement and apprehension.

The commission was expected to be the defender of human rights in the world’s largest democracy and to correct India’s dismal track record on this front.

Yet, instead of living up to its potential, it’s now being called a “silent spectator” to human rights violations in the country.

“The NHRC has not become an institution that makes a great effort to reach out to the public,” says Maja Daruwala, former executive director at the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI). Her verdict is harsh— the NHRC is “exclusivist” in its composition, disconnected from large sections of the population, and its mandate to promote human rights education “has not at all been realised by a long shot”.

If the NHRC loses its accredited A status, it could lead to a loss of credibility for India on the international human rights stage.

Also Read: Fact-finding isn’t easy in new India, more so for independent groups. What’s the way out?

A US official’s summer visit

In the peak summer of 1993, John R Malott of the US State Department visited New Delhi and turned up the heat. At the India International Centre, he questioned India’s human rights record in Jammu and Kashmir. He also conveyed US concerns over custodial deaths and rapes as well as the misuse of the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, or TADA.

The censure came at a time when India was newly opening up its markets and economy to the world through liberalisation.

Malott’s speech wasn’t the only criticism against India. In March 1993, Amnesty International released a report describing the killing of at least 53 men and women in J&K’s Sopore by the Border Security Force (BSF) in January that year.

(NHRC is a platform) where poor people, merely by sending a postcard or mail, can get relief

-Anil Parashar, retired joint registrar of NHRC

Robin L Raphel, assistant secretary of state for South Asian affairs, repeatedly brought up Kashmir, raising the hackles of the Narasimha Rao government. In one such “background briefing” for South Asian journalists in October 1993, she claimed Washington viewed Kashmir as a “disputed territory”. New Delhi was outraged.

India’s response to Malott was along the set template of sovereignty and national pride. The official spokesperson of the ministry of external affairs told the media that the country did not need “advice or exhortation” as “India’s commitment to human rights is second to none.”

However, the global criticism echoed loudly in Parliament during deliberations over the Protection of Human Rights Act.

Days before Malott’s New Delhi speech, on 14 May 1993, the government introduced the Human Rights Commission Bill. It was referred to a standing committee, while the President promulgated an ordinance establishing the NHRC.

There was scepticism from some quarters. Opposition MP George Fernandes, for instance, dismissed the NHRC as a “half-hearted effort”. He said that if it was just a fact-finding body, “then there is no need for it”.

Such sentiments did not prevail. The NHRC emerged as only the second commission of its kind in Asia—following in the footsteps of the Philippines.

This was in accordance with the Paris Principles— a framework that defines the minimum standards for national human rights institutions (NHRIs) globally, and was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 1993.

Right from the outset, both the NHRC’s leadership and its motivations for pursuing certain cases have been called into question.

Beginner’s zeal

In its fledgling years, the NHRC tried to live up to its lofty goals with bright-eyed zeal.

Anil Parashar spent 24 years of his career at the commission, and beams with pride when he reminisces about the early days. The NHRC actively pursued cases and “tried” every legal provision to take action, according to Parashar, who started as a special assistant to the chairperson in 1993 and retired as a joint registrar in 2016

He recalls the commission’s first suo motu case— the J&K Bijbehara massacre of October 1993, in which at least 37 people were killed when a BSF battalion opened fire to disperse a crowd of over 10,000 people.

While the NHRC’s cognisance of the Bijbehara incident was announced with trumpets blaring, the case did not lead to any form of justice for the victims.

Parashar also speaks of how the NHRC stepped in when policemen in Amritsar tattooed the words ‘jeb katri’ (pickpocket) on the foreheads of four women in December 1993. The NHRC intervention opened the doors for a CBI probe, which ultimately led to jail for the cops in 2016.

For Parashar, the NHRC is a platform “where poor people, merely by sending a postcard or mail, can get relief”. He points out that hundreds of crores have been disbursed as compensation on the NHRC’s recommendation.

“It depends on the leadership,” says Parashar.

However, right from the outset, both the NHRC’s leadership and its motivations for pursuing certain cases have been called into question. And it began with the very first chairperson of the NHRC, former Chief Justice of India Ranganath Misra, who leads a long list of commission heads to have courted controversy before assuming the post.

As a sitting judge, he headed a commission of inquiry into the large-scale killing of Sikhs during the 1984 riots following Indira Gandhi’s assassination. But the report was criticised for its lack of transparency and for absolving the Congress party of any role in the riots.

Some of his opinions on human rights were also controversial. In an August 1995 interview as NHRC chairperson, Misra defended “third degree methods” of interrogation. “It is in vogue and to a limited extent, if one does not use it, no investigation is possible,” he said.

The motivations behind the Misra-led NHRC’s taking up of the Bijbehara case raised some doubts too. “The exercise was necessary in the larger interest of the commission’s credibility when it exonerates the government,” legal scholar AG Noorani argued in a 1994 Economic and Political Weekly article.

Noorani’s words were almost prophetic. While the NHRC’s cognisance of the Bijbehara incident was announced with trumpets blaring, the case did not lead to any form of justice for the victims.

‘Hindutva’ controversy

In a 2000 article, Noorani called for an audit of the commission’s functioning and a background check of its members. He wrote that all three chairmen so far — Justices Ranganath Misra, MN Venkatachaliah and JS Verma—were “noted for their illiberal positions on civil liberties and especially on minorities.”

For Justice Verma, the ‘Hindutva cases’, as they collectively came to be called, were akin to an albatross around his neck. On 11 December 1995, Verma had delivered a judgment which held that seeking votes with reference to Hinduism or Hindutva did not per se violate the law.

Despite communal riots having flared up in Manipur since 3 May, the NHRC issued its first statement only on 20 July, after a video of two women being paraded naked by a mob went viral.

The verdict said that “the term Hindutva is related more to the way of life of the people in the subcontinent” and did not indicate bigotry. Another judgment by Verma ruled that BJP leader Manohar Joshi’s 1990 statement —“the first Hindu state will be established in Maharashtra” —was not illegal under electoral law.

Noorani, in the article, said that through these judgments, Justice Verma licensed the use of “rabidly communal Hindutva slogans in election campaigns”. He concluded that NHRC’s impact on national life was “slender”.

“The entire raison d’etre of the NHRC is simply to exist — to ‘answer’ charges of violations of human rights in respect of the insurgency-affected areas and cosmetically for the rest,” he wrote.

‘Politicisation’

The criticism that Justice Verma got for the ‘Hindutva cases’ is often offset by the praise he received for his work as the NHRC chief from 1999 to 2003. He is credited with swiftly setting the stage for justice in the February 2002 Gujarat riots.

The NHRC took cognisance of the riots for suo motu action as early as 1 March 2002, and indicted the Gujarat government for its failure to contain communal violence in the state in its preliminary comments on 1 April 2002.

On its website, the commission recognises the Gujarat riots intervention as one of the only two “significant interventions/landmark judgments”. The other one is its proceedings in Delhi’s Batla House encounter case.

In this instance, it gave a clean chit to the Delhi Police on the grounds that “there was no violation of human rights”. A year later in 2010, the commission conceded to never having visited the site of the encounter even once during its 11-month-long probe. The commission found the version of the Delhi police sufficient to rule out a fake encounter, it said.

Observers and experts like Henri Tiphagne, national secretary of the Human Rights Defenders’ Alert–India, express concern over the “politicisation” of the commission and its proactive selectiveness in some states, while ignoring crisis situations in others.

The point is they don’t feel for human rights, they don’t feel for victims of human rights, they don’t feel for the lives of those people

-Henri Tiphagne, national secretary, Human Rights Defenders’ Alert – India

Tiphagne contrasted the NHRC’s quick response to this year’s panchayat election-related violence in West Bengal with its delayed action to the ongoing ethnic conflict in Manipur.

“I don’t say you should not, but if the only rush is to West Bengal, where did that speed go in the issue of Manipur?” he asks.

Despite communal riots having flared up in Manipur since 3 May this year, the NHRC issued its first statement only on 20 July, after a video of two women being paraded naked by a mob went viral.

“The point is they don’t feel for human rights, they don’t feel for victims of human rights, they don’t feel for the lives of those people,” says Tiphagne, who is also national secretary of the All-India Network of NGOs and Individuals Working with the National and State Human Rights Institutions (AiNNI).

Today, the NHRC is the sole national body for human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir. One of the lesser-known consequences of the abrogation of Article 370 is the shutting down of the erstwhile state’s human rights commission after the two Union territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh were formed.

Earlier this year, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta told the Supreme Court that the NHRC would cater to Jammu & Kashmir as well. However, Tiphagne pointed out that the state human rights commission was closed despite pending complaints from the people of J&K.

“Why could the NHRC not step into the Supreme Court and say, abrogation is a different question but we are a human rights institution?” he asks. “The state human rights institution has been closed, unfortunately, as a result of your political act, but we want to save those complaints that were being handled by an SHRC, which today does not exist. Why did you (NHRC) not do it?”

From CAA to Article 370

The NHRC’s performance is now facing international scrutiny. Earlier this year, GANHRI, the largest global human rights network, expressed concerns in its report about the commission’s purported failure in taking “sufficient action in protecting the rights of marginalised groups including religious minorities”.

The report highlighted the NHRC’s lapses in reviewing laws related to civil liberties and fundamental rights. These laws, it said, include the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act 2010, Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967.

All three laws have been criticised for their alleged misuse against journalists, NGOs, government critics, and advocacy groups like Amnesty International, the Centre for Policy Research, and the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, leading to the cancellation or withholding of their FCRA licences by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

India cannot afford to lose its accredited A status which brings with it several privileges. GANHRI reviews and gives accreditations to NHRIs in compliance with the Paris Principles. The bodies that fully comply are awarded an ‘A status’. They enjoy independent participation rights at the UN Human Rights Council, its subsidiary bodies, and some General Assembly bodies and mechanisms. Losing this status could lead to a loss of credibility for India on the international human rights stage.

High pendency, staff shortages

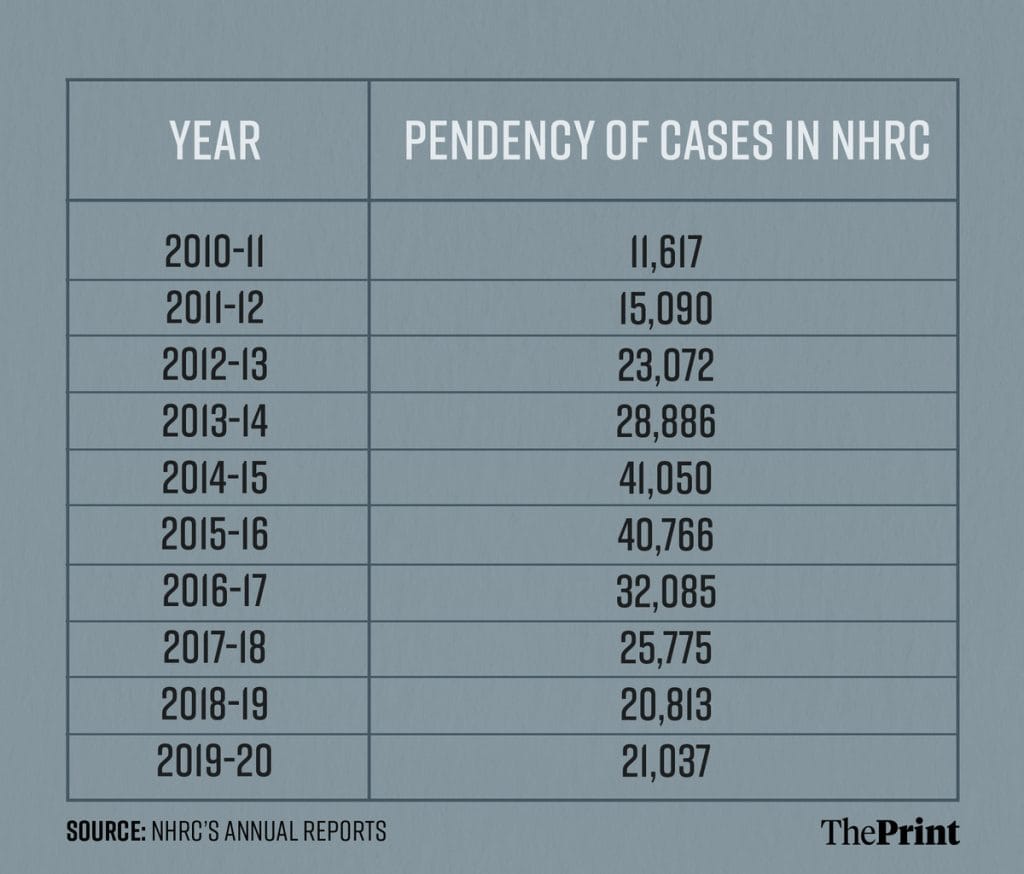

The NHRC, much like Indian courts, has seen a huge rise in backlog of cases over the years.

A perennial staff shortage–a problem it has been facing since its inception—has a part to play. The commission has only two members at present, against a sanctioned strength of five (excluding the chairperson). There’s a shortfall in other staff too. In 2018, the NHRC had 331 approved staff positions, of which 296 were filled. It also had 55 casual and contractual workers, and was awaiting approval for an additional 77 staff positions.

“More than 10 per cent of the approved positions are vacant at present,” according to a capacity assessment undertaken by the Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions (APF), United Nations Development Programme, Asia Pacific Regional Hub, and Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

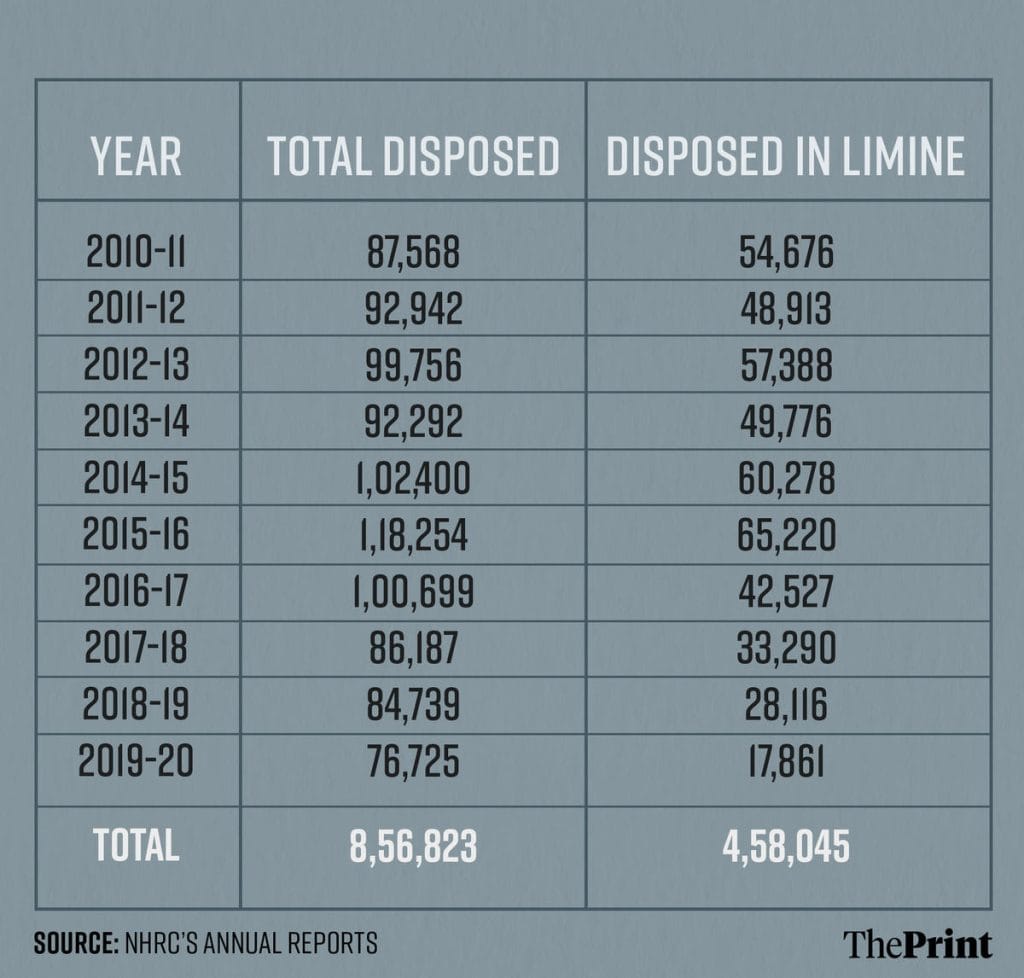

While the commission boasts of disposing of over 8.5 lakh cases from 2010 to 2020, a closer examination shows that 53 per cent of these cases were disposed of “in limine”, or ‘at the threshold’. This means that the complaints were not thoroughly examined and were dismissed on technical grounds.

Compensation is also a rarity in the cases disposed of by the NHRC. According to the NHRC’s 2019-2020 annual report, the latest available on its website, out of the 76,725 cases disposed of between March 2019 and April 2020, monetary compensation was ordered in only 0.5 per cent (437) cases. Out of the total number of compensation awards, only 0.14 percent (113 cases) had been complied with as of June 2020.

‘No institutional memory’

What happens to the reports that come out of the NHRC? Activist Harsh Mander’s resignation in 2018 provides a troubling answer to that question.

Mander was appointed to the NHRC in 2017 as a “special monitor” for matters relating to communal riots and minorities. And he got right to work, joining the NHRC mission to Assam’s detention centres in January 2018. Mander subsequently submitted a comprehensive report to the commission, with clear recommendations for the central and state governments.

However, he allegedly received no response regarding the actions taken based on his report. This became one of the factors that led to Mander’s resignation.

“It is apparent that there is no constructive role for the NHRC Special Monitor,” he wrote in his resignation letter.

Another civil society activist, on the condition of anonymity, also points to NHRC’s lack of action on several reports submitted to it.

“Go and ask them to show you their reports on prisons. Go and ask if they can find them. I know for a fact that there are over 50 reports on prisons. With 50 reports, you can’t decide what to do with prisons?” she says.

The problem, adds the activist, lies in the lack of “institutional memory” in the NHRC.

Approachability is another issue. “If you’ve got sandbags and policemen standing outside a human rights institution, who is going to come in there? It is a secluded building with sequestered commissioners,” the activist says of the NHRC’s Delhi office.

Policemen and peacocks

The NHRC is as good as its members and chairperson. But concerns over the appointments made to the commission have been a perennial problem.

In 2004, the NDA government appointed former CBI director PC Sharma as a member amid “raging controversy”. There was resistance from within the NHRC as well, with chairperson at the time Justice AS Anand opposing the decision.

The People’s Union of Civil Liberty (PUCL) challenged the appointment in the Supreme Court, asserting that the appointment of a former police officer would affect the faith of the people in the commission. The petition was rejected by the Supreme Court, but that did not stem the tide of criticism.

Noorani wrote an article titled A Policeman as Judge? against the appointment and Ravi Nair resigned from the NHRC’s NGO core committee, a monitoring body and helps coordinate with NGOs in human rights violation cases.

When human rights are at stake, who chooses the protectors becomes as important as the protectors themselves. But the selection process of the NHRC has come under the scanner for its lack of transparency.

Members of state human rights commissions have similarly come under criticism. Former Rajasthan High Court judge Mahesh Chandra Sharma’s appointment as a member of the Rajasthan Human Rights Commission (RHRC) in October 2018, created a stir. His claim to fame was his media interaction on the last day of his judicial career in 2017 where he praised the cow and the peacock for their piousness.

“The peacock is a lifelong brahmachari (celibate). It never has sex with the peahen. The peahen gets pregnant after swallowing the tears of the peacock,” he had said. Sharma’s comments came after he issued an order calling for the cow to be declared the national animal.

A couple of years later, as part of a two-member RHRC bench, Sharma, along with panel chair Justice Prakash Tatia equated women in live-in relationships with “concubines”.

The current NHRC chairperson, Justice Arun Kumar Mishra, also drew flak for calling the Prime Minister a “versatile genius” when he was a sitting apex court judge.

Mishra was appointed in 2021, and was the first chairperson to assume the position after the Narendra Modi government revised the eligibility criteria. Earlier, only a retired CJI could be appointed as NHRC chairperson, but the amended law allows retired SC judges to be considered as well.

The role of the police is another thorny issue. Thirty years ago, in an article published on 23 October 1993, civil liberties advocate PA Sebastian addressed the need for the commission to have its own “independent investigative machinery, appointed by and accountable to itself”.

If you’ve got sandbags and policemen standing outside a human rights institution, who is going to come in there?

-Civil society activist

This holds true even today. A large chunk of the complaints the commission receives pertain to police action or inaction—whether it is custodial violence or encounter deaths.

But there’s a catch— the NHRC investigates complaints related to police actions through its investigation wing, comprising serving police officers.

“It is too much to expect that the same police will investigate and bring their colleagues to book,” wrote Sebastian.

Tiphagne has no problem with the police being used by the commission, but offers another solution—the probe arm of the NHRC needs to be a human rights investigation wing, not a criminal investigation one.

Tokenism

When human rights are at stake, who chooses the protectors becomes as important as the protectors themselves. The selection process of the NHRC, however, has come under the scanner for its lack of transparency.

The President of India appoints the NHRC chairperson and members based on the recommendation of a committee comprising the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the Union home minister, the leaders of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, and the deputy chairperson of the Rajya Sabha.

But in its 2023 report, GANHRI noted that the selection process is “not sufficiently broad and transparent”. This is a recurring criticism. GANHRI’s reports for 2006, 2011, 2016, 2017 and 2023 have all demanded an overhaul of the appointment process.

One of the issues raised is that the selection process does not require the advertisement of vacancies. It also does not specify the process for applications, screening, and appointment.

The exclusion of certain groups from the commission has also garnered attention, including women, religious minorities, and SCs, STs, and OBCs.

When Justice Arun Mishra was appointed to the commission, Leader of Opposition in Rajya Sabha Mallikarjun Kharge criticised the government for “refusing to consider any SCs, STs, OBCs or minorities”. He also said that “the appointments smack of partisanship and quid pro quo”. Kharge is a member of the selection committee for the commission, making his comments all the more remarkable.

The lack of “pluralism” in the NHRC’s composition has been consistently flagged by GANHRI in its accreditation reports.

To address this, the Protection of Human Rights Act was amended in 2019 to increase the number of commission members from four to five, including one woman.

However, activists like the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative’s Daruwala point out the “tokenistic” nature of the amendment. And as of the latest GANHRI report, neither of the two current NHRC members are women.

The report also pointed out that of 393 staff positions listed by the NHRC, only 95 are held by women. It has recommended that NHRC should complete the appointment process to fill the remaining vacancies and also amend the Protection of Human Rights Act to ensure a “pluralistic balance” in the composition and staff.

In the 30 years of its existence, the commission has had just three women members— Justice Fathima Beevi, Justice Sujata Manohar, and Jyotika Kalra.

Kalra quit in January 2018—eight months after she had joined— alleging a “discriminatory attitude” towards her.

In her resignation letter, she accused the commission of limiting members’ power to take suo motu cognisance of human rights violations. Kalra, however, re-joined the commission in March that year, and went on to serve her full term.

“Fifty per cent of the complaints in the commission are by women or concerning women and children. Imagine a body that deals with women’s issues on such a large scale, but there is no woman representation on the NHRC,” Kalra tells ThePrint.

Also Read: Lack of funding, underequipped labs — a study by NLU’s Project 39A finds gaps in Indian forensics

‘Not even an ornamental body’

The NHRC’s track record reveals more misses than hits, more omissions than commissions, and more controversies than accolades.

Former Supreme Court judge Justice Madan B Lokur calls it “tragic” .

“The NHRC must appreciate that it has to shoulder a responsibility, not perform a duty. This realisation does not exist today,” he says.

The warning bells that were sounded decades ago on the NHRC’s scope being at risk are still tolling.

In his October 1993 article, activist PA Sebastian wrote about the commission ending up as “another ornamental body” in India. But lawyers, experts, and human rights activists that ThePrint spoke to say that the situation is even worse than this.

According to Tiphagne, the reality may be bleaker than Sebastian’s warning.

When seeking investigations into the Manipur violence and the December 2019 ‘encounter’ killings of four suspects in the Hyderabad rape and murder case, the courts bypassed the commission, he points out.

“The judiciary of this country doesn’t consider it even ornamental,” he says.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)