A petition to clean up a south Delhi stormwater drain reached the National Green Tribunal nine years ago. Environmental activist Rajeev Suri spent four years trudging in and out of the tribunal asking for a strongly worded order against civic bodies. In vain. Finally, the petition was tossed aside.

“When we filed the petition, we were very hopeful. But the case went on for years and during that time, many judges came and retired. Ultimately, nothing came of it. We had to move the Supreme Court,” Suri says.

Meanwhile, the Kushak drain, which flows through several upscale neighbourhoods, continues to be clogged.

In the sprawling courtroom of the NGT, several petitioners like Suri have met with a similar disappointment. What was a grand strategy to create a parallel environmental structure for grievance and unclog the Supreme Court has fallen woefully short of its promise and potential.

Established in 2010 for “effective and expeditious disposal” of environmental cases, the National Green Tribunal, say petitioners, lawyers, and government officials, has been deviating from its core mandate. The institution was UPA’s flagship project and pegged to be in the big league of RTI and RTE reforms. But the government support hasn’t matched the needs and role of the institution that has never functioned with full strength since its inception. In its pursuit of speedy justice, the NGT has lost some of its earlier sheen and trust it enjoyed among both petitioners and the lawyers. Environmental justice has paid the biggest price, with cases languishing for years and judgments not addressing the core dispute. The tribunal has been accused of overstepping its jurisdiction, imposing unrealistic fines and at times completely ignoring violations. For large parts of its existence, NGT’s work has been “person-centric” — characteristic of the judge heading it — and not “process-centric”. The biggest question mark on its functioning has been placed by the Supreme Court itself.

“The NGT was once abuzz with activity by seekers of environmental justice, but its vibrancy is no longer visible. There was a time when NGT’s interventions were causing discomfort to business interests. There were environmental clearances that had better scrutiny, violations in coal mining were being reported and discussed, and government agencies were not being allowed to just undertake projects arbitrarily. The Tribunal was becoming an impediment in the government’s mindless developmental agenda and so steps were taken to restrict it,” Suri told ThePrint.

The tribunal has dealt with a range of environment related issues, from pollution, mining, and waste management, to even directing pilgrims to maintain silence while standing in front of the Amarnath Temple’s ice Shivling.

The Supreme Court, in January this year, said that the NGT’s practice of passing ex-parte orders and the imposition of damages amounting to crores of rupees, “have proven to be a counterproductive force in the broader mission of environmental safeguarding.”

Lawyers also say that the choice of the chairpersons has impacted the institution — the green tribunal often taking on the color of its head.

Suri says the institution hasn’t been “green” over the last few years — implying the increasing apathy of the tribunal towards environmental cases.

Also read: Lynched Muslim man told fellow migrants people in Haryana are nicer than in Delhi

The golden era

In March 2010, when Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh moved the Green Tribunal Bill in the Lok Sabha, he placed the legislation in the big leagues, comparing it to the Right to Information and the Right to Education.

Compared to its two predecessors — the National Environment Tribunal (1995) and a National Environment Appellate Authority (1997) — the NGT does have wider powers. It can look into “substantial questions” related to the environment, as well as hear appeals against decisions on forest and environment clearance.

But it was off to a rickety start. It’s first head, Justice LS Panta, barely lasted a year, leaving the tribunal in dire need of a person who could take it to the heights of environmental glory.

Enter former Supreme Court judge Justice Swatanter Kumar. Several lawyers who ThePrint spoke to called his tenure the “golden era” of the NGT.

Environmental lawyer Ritwick Dutta recalls that initially, nobody would respond to the notices issued by the NGT. However, with Justice Swatanter Kumar’s appointment in December 2012, all that was about to change.

“Justice Kumar began a revolution.”

Justice Kumar issued bailable warrants of arrest against government officials. And the tribunal’s work gained press attention — NGT issues bailable warrant against Delhi chief secretary; NGT issues bailable warrant for top cop; NGT issues bailable warrants against four rail officials in Delhi; Biological Diversity Act: NGT issues warrants against states, UTs.

Dutta says this had a “huge impact”.

“Overnight, everybody started saying even if you don’t go to other courts, you have to go to the NGT.”

The NGT was suddenly in the big leagues, with senior counsels and advocates generals appearing before it, pleading on behalf of the state governments, central government, and government departments.

Dutta credits Justice Kumar for his “no nonsense approach”.

“He (Justice Kumar) made it the most happening place for lawyers to come, because there was scope for arguments. That made the NGT happening,” he says.

And the tribunal didn’t limit its role as a mere judicial institution. Soon after it received a new address in the capital, it saw several international conferences held that garnered global attention.

“Justice Swatanter Kumar came in, and that really set the ball rolling. As a fledgling institution, it needed that kind of leadership,” said Senior Advocate Sanjay Upadhyay, former Managing Partner of Enviro Legal Defence Firm. “It almost became an institution which was known globally, with international agencies coming in, tying up and partnering with us.”

The reviews of the tribunal, early on, were promising.

A 2018 study published in Springer analyzing the judgements made by NGT showed that between 2011 and 2016, there was a consistent spike in the number of judgements.

The analysis shows that during this period, 2,051 judgments were issued, ranging from cases related to the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Cess Act, the Forest (Conservation) Act, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, the Environment (Protection) Act, the Public Liability Insurance Act, and the Biological Diversity Act, among others.

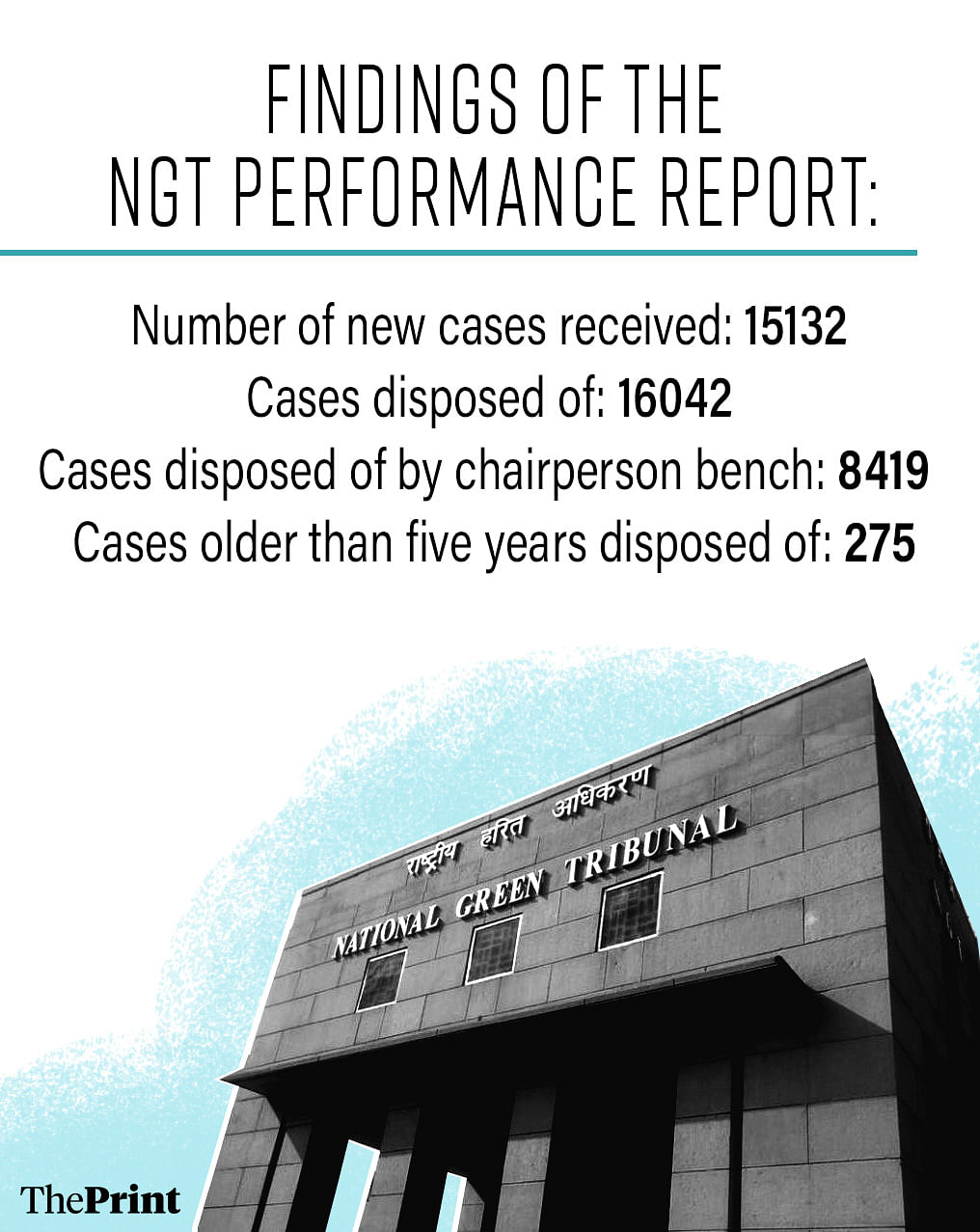

Between 2018 and 2023, the NGT claimed to have “disposed of” 16,042 cases. However, it is unclear as to how many of these matters were decided on merits or dismissed at the threshold.

A month before Justice Kumar retired, the World Commission on Environmental Law, the Global Judicial Institute on the Environment, and participants from across the world paid tribute to him in an international conference in Delhi.

Also read: Lalbagh to Seattle—Bengaluru’s 100-yr-old MTR chain goes international like Saravana Bhavan

Growing trust, dwindling manpower

NGT’s journey as the provider of environmental justice began from a small office in south Delhi. Soon, this lack of infrastructure reached the Supreme Court too.

The tribunal was initially housed at two places — a bench at the Van Vigyan Bhawan in R.K. Puram, and another at the Bhikaji Cama Place.

Jairam Ramesh had argued the tribunal should be in Bhopal, the site of one of the “worst industrial tragedies”. However, the government settled for Delhi for administrative reasons.

In May 2012, the Supreme Court directed the Centre to allot the entire 36,000 square feet space available in the capital’s heritage Faridkot House — which was being used by the National Human Rights Commission — to the NGT. The tribunal finally found a new address in October 2013, on its third foundation day.

A new home though could not plug the key resource gap.

The 2018 Stringer study said that while environmental cases found a dedicated home for redressal, the tribunal was battling issues of manpower and facilities, which was making it difficult to keep up with the six-month case disposal deadline.

“There may be enormous pressure on NGT, which needs more manpower, probably in the context that NGT aims to dispose of cases within six months,” the analysis read.

The lack of members continues to drag NGT’s work.

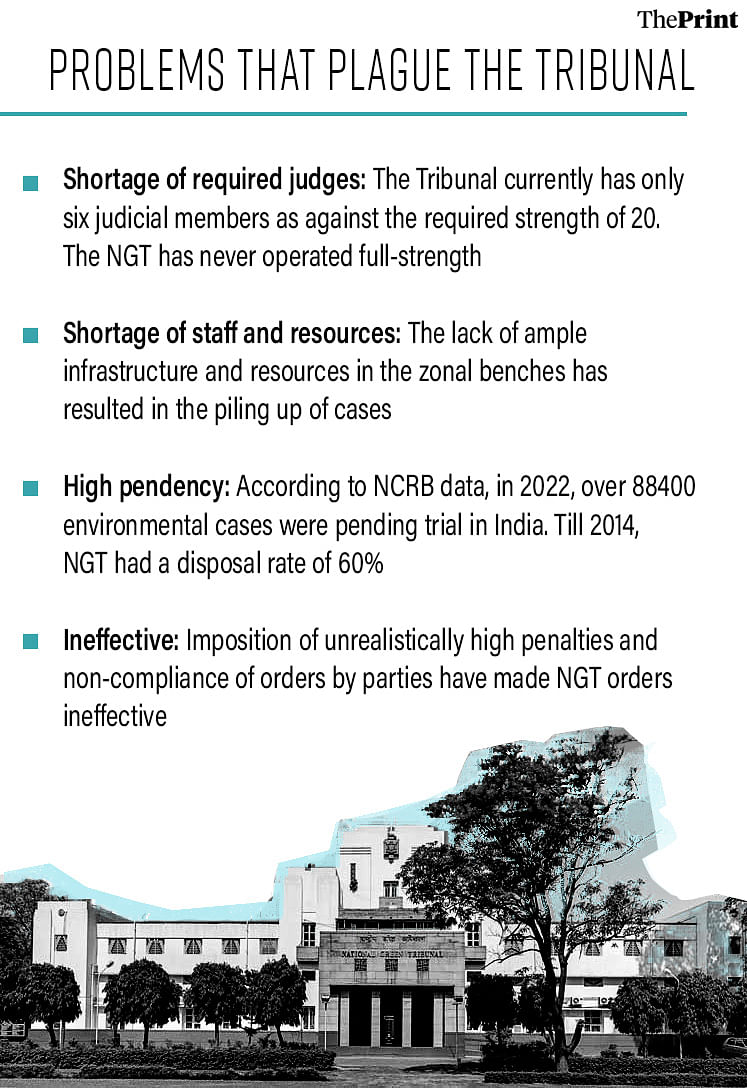

The NGT Act provides for 10 benches in five zones — northern, southern, central, eastern and western — with two courts in each zone. It, therefore, mandates appointment of a chairman and 20 members — 10 judicial and 10 experts — who constitute the benches. However, NGT has never had full strength ever since it was set up. Owing to the vacancies, several of its regional benches often get defunct, burdening the principal bench in Delhi.

According to a report, there may be enormous pressure on NGT, which needs more manpower, probably in the context that NGT aims to dispose of cases within six months

Currently, it has five expert members and six judicial members, one of whom, Justice SK Singh was set to retire in January last year but is currently serving on an extension.

According to experts, the process has especially been slow since the government modified the rules in 2017 to hire members for tribunals. The amendment gave the government an upper hand in recommending members. While the Supreme Court set aside the 2017 rules, the new ones framed thereafter also came under the top court’s scrutiny, but were upheld with some modifications.

Also read: Rs 4,800 cr IPO bids are now making Delhi bike dealer nervous. Mountain of paperwork is next

The committee-raj…

When Justice Adarsh Kumar Goel replaced Justice Kumar as the Chairperson in 2018, lawyers and litigants didn’t know what was to follow. Within a month of assuming office, Goel alleged that 50 per cent of the cases before the tribunal were being filed by “blackmailers”.

“Earlier, we used to issue notices…But now we are not issuing notices and disposing of the cases,” Justice Goel was quoted as saying.

Upadhyay says this was the time when NGT turned into a court without lawyers, with everybody being seen with “suspicion”.

“I can understand three years down the line, you have some data to back that up, and you say something like this…He came with a presumption that there are certain lawyers, especially the biggies, who are hand in glove,” says Upadhyay.

Justice Goel’s tenure came under scrutiny for making the justice system weak. It was called the “committee-raj” where the NGT relied exclusively on expert committee reports to pass orders, often at the cost of hearing the parties and their lawyers.

The Committee’s reports being considered the “gospel truth” was “discomforting”, Supreme Court advocate-on-record and Partner at VSA Legal, Sumeer Sodhi told ThePrint.

The Supreme Court had then stepped in, observing that the adjudicatory functions of the NGT cannot be delegated to administrative expert committees.

Justice Goel’s tenure came under scrutiny for making the justice system weak. It was called the “committee-raj” where the NGT relied exclusively on expert committee reports to pass orders, often at the cost of hearing the parties and their lawyers.

“There was a big distance that was created between the bar and the bench that was felt…when Justice Goel took over, there were confrontations between the bar and bench that could have been avoided,” Sodhi says. He also referred to the international seminars being organised during Justice Kumar’s tenure.

“However, all of that stopped immediately. There were no international conferences where the bar and the bench stood together,” says Sodhi.

Also read: Gurugram has a king of good times. Lakeforest Wines is both liquor monopoly & a renaissance

…and its fallout

In 2023, Justice Goel demitted office in a lonely farewell, in stark contrast to Justice Kumar’s that saw lawyers hobbling around the judge to click selfies.

In a report titled Bird’s eye view of NGT performance in the last five years (July, 2018 – July, 2023), the NGT says that it received 15,132 new cases and disposed of 16,042 cases. The chairperson’s bench alone disposed of 8,419 cases.

But the absolute reliance on expert committee reports meant that the tribunal did not hear the lawyers of various parties involved in these cases, snatching away the rich, argumentative atmosphere that’s the hallmark of a judicial forum.

With the establishment of the NGT, and its growth as an institution building environmental jurisprudence, several prominent lawyers dedicated their practice to environment matters. However, lawyers now claim that Goel’s tenure had led to several of them moving away from the NGT.

“Lawyers stopped coming to NGT because nobody wanted to be in a court where you are not heard,” says Sodhi.

Sodhi recalled that in 2018, when he was part of the executive committee of the NGT bar association, the collective had around 190 lawyers. This number has now dwindled to around 30-40.

Petitioners have also admitted to moving away from filing cases in the NGT and preferring the High Court for interventions in environmental cases.

“We do prefer filing environmental petitions before the High Courts now. It is more open and sensitive to environmental cases and has a better track record in giving strong judgments,” says an environmentalist who did not wish to be named.

Also read: Malayalam cinema is a Boys’ Club. Its progressive tag coming apart with Hema Committee report

Angry young tribunal?

While the NGT’s functioning may have been impacted by who is heading the tribunal, its temperament toward violators has remained mostly consistent. Violators are often slapped with hefty fines — the tribunal ensures that the polluter pays for the damage it causes and is wary of causing any further damage.

By the tribunal’s own admission back in May 2023, it had imposed fines of about Rs 80,000 crore on states and Union territories just for non-compliance of sewage treatment and garbage disposal rules and for violating orders. An October 2022 analysis by Down To Earth magazine had also found that an NGT bench headed by Justice Goel had imposed fines of about Rs 30,000 crore on seven states within just five months from May to October 2022.

As per the law, the NGT has two jurisdictions.

The first is called the ‘original’ jurisdiction of the tribunal, under which the NGT can take up all “substantial questions” related to the environment which affect the community at large and where there is a violation of environmental laws. Second is the ‘appellate jurisdiction’ which gives the NGT power to hear appeals against centre as well as state government decisions on forest clearance and environment clearance for infrastructure projects.

The NGT also looks into issues of compensation and order for restoration of the environment.

Dutta told ThePrint that the NGT now uses the Central Pollution Control Board’s (CPCB) 2018 methodology for assessing penalty and environmental compensation. In its 2023 report, the NGT also clarified that the compensation is worked out broadly on principles of restitution, considering the cost of restoration with an element of deterrence and the paying capacity of the violators and the extent and nature of the violations.

The 2018 report had an illustrative list of 35 cases showing application of the ‘polluter pays’ principle. However, ThePrint found that at least 11 of these cases have either been challenged, stayed, or set aside by the Supreme Court.

Most of the pollution has happened because of the lethargy of the pollution control board, whereas when a citizen goes and files a case, the benefit is going to the pollution control again. So what we find is that there is a very mechanical approach

– Ritwick Dutta, Environmental lawyer

For instance, in January 2019, NGT directed the Meghalaya government to deposit Rs 100 crore as an interim measure with the Central Pollution Control Board, in a case related to the threat to life arising out of coal mining in south garo hills district. Meghalaya challenged this in the Supreme Court. It submitted that Meghalaya has limited sources of revenue and putting an extra burden of Rs 100 crore will shatter the economy of the state.

Agreeing with the state government, the court allowed Meghalaya to transfer the amount of Rs 100 crore from the Meghalaya Environment Protection and Restoration Fund to the CPCB, to utilise it for restoration of the environment in Meghalaya.

Dutta points out another concern over such orders. He says even if there’s damage to a person’s land or agriculture due to environmental damage, the compensation often goes to the pollution control board for its restoration.

“Most of the pollution has happened because of the lethargy of the pollution control board, whereas when a citizen goes and files a case, the benefit is going to the pollution control again. So what we find is that there is a very mechanical approach,” he said.

Also read: Edtech partied long on VC cash. Now, the hangover—long hours, job loss, pay cuts, targets

Pollute and pay

In 2016, Bengaluru-based spiritual group Art of Living organised a three-day cultural event – World Cultural Festival – on the Yamuna floodplains, which placed the tribunal under the scanner by environmentalists.

Over a month before the event was scheduled between 11 and 13 March, environmentalist Manoj Mishra filed a petition before the NGT to stop it. The petitioner, a former Indian Forest Service officer, highlighted that the event risked further degradation of the ecologically sensitive Yamuna floodplains. But the NGT didn’t stop it.

The event set up a seven-acre stage–believed to be the largest in the world back then–capable of accommodating over 35,000 dancers and hosting around 35 lakh people on the fragile Yamuna floodplains.

According to activists, the idea behind moving the NGT was to stall the event, which was quoted as being an “environmental disaster” by petitioners. What followed, however, was a series of delayed, abrupt, and ineffective orders by the tribunal.

The treatment of the case in the NGT led to the organisers skirting responsibility for the damage caused to the floodplains. An Expert Committee set up by the Tribunal confirmed that the event had damaged the vegetation in the floodplains, had compacted and leveled the soil and constructed temporary structures that damaged the ecology.

An analysis by the expert committee of the case released in 2020 highlighted how the NGT initially imposed a fine of Rs 120 crore on the organisers. After objections from the organisers, the amount was abruptly reduced to Rs 28.73 crore, with an advance payment of only Rs 5 crore.

The NGT was also blamed for not holding any government agency responsible for granting permissions for the event.

“The case is interesting and NGT has been heavily criticised for how it dealt with the issue. The tribunal was constituted for giving a concrete shape to the State’s commitment towards our concern for the environment and is perhaps the most important and empowered body to decide cases of environmental issues and damages caused to it,” a blogpost by lawyer Rangita Chowdhury reads.

She adds that “the judgment thus stamped the policy of ‘pay and pollute’ and encouraged the exploitation of the environment. The case has set a bad precedent for the future; it is likely to encourage parties to use the judgment to their advantage and undermine our fight against environmental damage.”

The organisers, however, have their own complaints from the NGT. In an email response to ThePrint, Art of Living said that they have moved the Supreme Court against the Tribunal’s verdict and are awaiting a hearing.

“The National Green Tribunal decided to levy a fine of R120 crore alleging damage to the Yamuna floodplains when there was none…No study was conducted before the event to assess the ecological status of the site, and yet, post-event, we were held responsible for alleged damages that were never quantified,” the response read.

The organisers also added, “It is also worth noting that independent experts have challenged the NGT’s findings, pointing out that the conclusions drawn were not scientifically robust.”

Also read: Tamil Nadu is on a mangrove mission to create ‘bio-shields’. Villagers are on the frontlines

Waiting for Godot

Back in 2018, the ‘garbage gangs of Deonar’ caught the NGT’s attention.

Moved by a news article on how mismanagement of solid waste had an adverse impact on the environment, public health and lives of individuals living in the vicinity of the dumping ground in Mumbai city, the NGT took suo motu cognizance.

However, the initiative was challenged in the Supreme Court, raising questions over whether the NGT could have taken suo motu cognizance of the issue at all.

This initiative led to the Supreme Court clarifying in October 2021 that the NGT is a “unique” forum with suo motu powers to take up environmental issues from across the country. The court had asserted that the NGT need not indefinitely wait for the “metaphorical Godot” to knock on its doors to save the environment.

In a tweet, Congress leader Jairam Ramesh hailed the decision, saying that “despite the Modi Sarkar’s systematic efforts to weaken it since 2014, the NGT has received the strongest possible endorsement of the Supreme Court”.

Ever since, the NGT has routinely taken suo motu cognizance of newspaper reports, as well as letter petitions on environment-related incidents — from water supply to Chinnaswamy Stadium for IPL 2024 amid Bengaluru water crisis to overflowing sewers for the past two years in the Sushant Lok 1 colony of Gurugram.

However, Dutta points out that a bulk of the cases before the NGT are now suo motu cases.

Once a case is taken up suo motu, the court then demands responses from government authorities on alleged violations and may or may not appoint an amicus curiae to assist it.

In Dutta’s view, taking the suo motu route frequently excludes any petitioners who may have approached the tribunal later.

“Because the court has taken suo motu and the proceeding becomes one between the state and the court and without the intervention of the public. So you are actually excluding the public from the general discussion, and it is between the government and you,” he says.

Dutta refers to the NGT taking suo motu cognizance of a news article revealing 6,00,000 fake Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) certificates by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) from audits at four plastic-recycling companies in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka. While the NGT was quick to act, the matter has now been listed before the Central Zone Bench of the tribunal at Bhopal in November.

Asserting that suo motu cognizance should be an exception rather than the norm, he says, “it’s important to ensure that hearings take place more regularly, especially given the legal requirement that cases should be decided within six months.”

According to him, taking up suo motu matters immediately and then fixing the next date of hearing three or four months later “defeats the purpose of suo motu and speedy justice”.

In January this year, the Supreme Court also pulled up the NGT for its “recurrent engagement” in “unilateral decision making”. The court was hearing appeals challenging compensation imposed by the tribunal in suo motu proceedings on a man being charred to death in Delhi after an illegal factory caught fire. The appellants alleged that the compensation of Rs 96 lakh was imposed on the landlord and tenants of the building without hearing them.

The top court cautioned that in “its zealous quest for justice, the tribunal must tread carefully to avoid the oversight of propriety”.

Also read: Haryana Khap has come a long way for women in 2 decades. Only for the medal-winning ones

A widening gap

An early study conducted by the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) in 2014 showed that while the NGT did much better in disposing of cases than lower courts, its pendency was still quite high.

The analysis showed that 96 per cent of cases filed by the state pollution board of Chhattisgarh, 76 per cent by Odisha, and 55 per cent of cases by the Karnataka pollution board were pending in the lower courts.

Meanwhile, within four years of its establishment, NGT disposed of 3,458 out of 6,017 petitions filed before it—a disposal rate of 60 per cent.

Experts, however, say that the gap has widened since this study.

Two senior officials from the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, who wished to remain anonymous, say that the green tribunal has strayed from its original design. Many benches have tried to “overstep its jurisdictional powers”. This included levying heavy fines on individual officers, reprimanding departments for not appearing for hearings and delaying projects.

Officials say that this not only caused a pile-up of cases but also paved the way for a higher number of appeals to higher courts.

“If you give unrealistic judgments and impose fine amounts that cannot be retrieved, you will not be able to stick to the purpose you were formed for,” one of the two officials from the environment ministry told ThePrint.

The official conceded that the NGT has reprimanded the government on several cases. But in most of these cases, the judgments have favored the government during higher appeals.

Also read: At 90, scientist CNR Rao is still driving breakthroughs at JNCASR. More research, less red tape

New green bottle

Old wine, new green bottle — that was the title of an article Upadhyay wrote for Livemint in 2009, questioning the idea of the National Green Tribunal that was then still in the works. The article made a fervent appeal for a “rigorous examination” of the National Environmental Tribunals and the National Environment Appellate Authority that either didn’t find success, or didn’t see the light of the day.

He says that any new institution must assess why the previous one failed. According to him, no such exercise was undertaken before the NGT was brought in to understand why the NET of 1995 could not be notified, or why the NEAA remained headless for several years and had to be eventually dissolved.

According to him, the direct result of this is that such an institution becomes “person-centric” and not “process-centric”.

“So when you have a charismatic chairperson, then he or she runs and takes it ahead the way he or she wants it,” he says.

Former Calcutta High Court Chief Justice Prakash Shrivastava was appointed as the NGT chairperson in August last year. In his appointment, lawyers and petitioners see a glimmer of hope. They are optimistic the new chairperson will clean up some of the cobwebs.

Suri is dusting off his old files and getting back to research. He plans to file a new petition before the green tribunal.

“We are hopeful that things will be different under the new chairperson. When you are fighting for the environment and the future of your children, you have to remain positive,” he says.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

Such efforts -NGT- do not work

NGT has no real teeth and its bite is inconsequential

Simply put those who fail to obey the adopted environmental regulations should be punished even if they are IAS officers.

Obeying civic rules is not fashionable

One option is to stop all construction of homes and commercial buildings in a city because the City government is not following the rules by Court order. Then the power structure takes action

It has worked in other countries

The NGT was never a “grand” structure. It is an incompetent institution meant for post retirement employment of complaint SC judges.

The sooner it is scrapped, the better it will be.

It was the brainchild of the National Advisory Council (NAC) – a patently unconstitutional body.