New Delhi: At a tea shop in Agra, a letter is being drafted to be sent to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. They are quibbling over a word here and a word there and the right time to send it. But the singular message they want to send in the letter is clear: reservation of 9 per cent for Muslims out of the 27 per cent OBC quota.

Elections are approaching; there’s much talk about caste census, jitni abaadi utna haq (the more the population, the more the rights), and Bihar’s 65 per cent reservation. And Sami Agai, president of the Agra-based Bharatiya Muslim Vikas Parishad, wants to time the letter just right. His organisation has been advocating for the rights of Pasmanda Muslims since he founded it in 2016. It is among the many grassroots organisations in India fighting for the future of Pasmanda youth—men and women who have been socially and culturally marginalised, but want to be part of the mainstream. They dream of becoming journalists, doctors, professors, policy makers, and leaders. And most of all, they want a stake in government jobs.

“We feel cheated. Wherever Modi goes, he mentions Pasmanda Muslims and their castes. If they are so concerned, then why don’t they include us in Article 341? We see a difference between the PM’s actions and his words,” says Agai, referring to the clause that allows for the inclusion of new communities in the Scheduled Castes (SC) category. But his bitterness is tinged with hope that Modi will pay more than lip service to Pasmanda Muslims. They make up nearly 85 per cent of the Muslim community in India. These demands can potentially be inflammable in a Hindutva-dominated India. But Muslims want the Pasmanda outreach to mean more than just voting for the BJP.

India’s Muslim politics is shifting— from religion to reservation. Modi and BJP’s outreach to the Pasmanda community, on the one hand, fuelled aspirations of job quotas in the government sector. But that was short-lived. Just before the Karnataka elections, the Basavaraj Bommai government at the time dashed their hopes by removing the 4 per cent OBC quota for Muslims in the state, and Home Minister Amit Shah spoke of ending reservations in Telangana. The last time the issue became a lightning rod for the BJP and Hindutva groups was when former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh spoke about minorities and marginalised communities having the “first claim” on the nation’s resources.

Now, in the run-up to the upcoming elections in the states and the Centre, this has once again become the new promise — instead of protecting Muslims with secular politics, they are pitching them job quotas. Ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha and Assembly elections, the Congress in Maharashtra raised the issue of restoring the 5 per cent quota for Muslims, and the Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) said it’d raise it from 4 to 12 per cent if voted to power. The Congress, which is back in power in Karnataka, has promised to restore the 4 per cent reservation quota.

We feel cheated. Wherever Modi goes, he mentions Pasmanda Muslims and their castes. If they are so concerned, then why don’t they include us in Article 341?

-Sami Agai, president of Agra-based Bharatiya Muslim Vikas Parishad

But many say that there is an unmistakable irony in expecting job reservations at a time when the Muslim community is being stereotyped, vilified, and pushed aside in India’s new politics of cow vigilantist violence, love jihad, CAA-NRC, UPSC-jihad, and bulldozers. The government has also ended minority pre-matric scholarships and the Maulana Azad Fellowship for minority students in higher education. Even the budget of the Ministry of Minority Affairs was slashed by 38 per cent this year.

Many in the community say that just as a new generation of educated, middle-class Muslims got ready and were aspiring to join the formal workforce in the post-reforms India, the politics turned dark. And reservation hopes are springing again.

Muslims—both Pasmandas and those from upper castes—want political representation at the national level, seats in universities, and government job quotas. But not everyone wants reservations like SC, ST, and OBC. It’s a bouquet of options thrown up by the community.

While a section of the Muslim community advocates for reservation for the entire community, some individuals are demanding the implementation of population-based reservation.

The Muslim Vikas Parishad is among the organisations fighting for backward Pasmandas to be included in the Scheduled Caste list. It’s become a rallying cry of lesser-known local political parties like the Uttar Pradesh-based Rashtriya Ulama Council. The party mobilised Pasmanda Muslims in Uttar Pradesh, Assam, and Delhi for the 10 August nation-wide protests against the exclusion of Dalit Christians and Muslims from being recognised as ‘Scheduled Castes’.

The conversation is not limited to protest marches and rallies. It’s become a hot-button topic on campuses from Jamia Millia Islamia to Delhi University—through parchas (pamphlets), posters, and petitions.

This month, for instance, AISA released a black-and-white pamphlet advocating for the creation of a separate Scheduled Caste category within the Muslim community and calling for the removal of the 50 per cent reservation cap.

“Muslims have fallen far behind because of the policies of the Modi administration,” says 32-year-old Mohammad Waqar, a PhD student from Jamia Millia Islamia who is part of the All India Students’ Association (AISA).

Their quota demand aims to compensate for the setbacks young Muslims are facing because of budget cuts.

The feeling of ‘second-class’ treatment by Muslims within their own community is something Pasmandas are railing against.

Also Read: AMU asked for certificates proving students are Ashraaf till 1947. Nothing has changed

Campus mobilisation

The Bihar caste census and the recent 65 per cent reservation Bill passed by Nitish Kumar government have reignited 31-year-old Pasmanda Muslim Lal Chand’s interest in reservation. The PhD student from Jamia Millia Islamia is waiting to hear back from the education department in West Bengal where he has applied for a professor post under the OBC category.

“If I was in Uttar Pradesh or Karnataka, I would not have been able to apply under the reserved category because I am a Muslim,” he says. Lal Chand is only the second person from his village in Malda, West Bengal to pursue a PhD. That he has come so far is because of his understanding of reservation and the politics around it, he says.

“I have seen people from my community who left their MPhil and started working as cab drivers because they were afraid that they would not get jobs,” says Lal Chand.

We are already backward. Islamophobia has brought us to this point. We have seen the Jaipur train hate crime, the murder of Junaid and Nasir, and riots. We are facing exclusion

-Aman Qureshi, former student who is active with DISSC

Pasmanda Muslim rights and reservation is a much-debated topic within organisations like AISA, the Student Islamic Organisation (SIO), and the Dayar-i-Shauq Students’ Charter (DISSC). They are mobilising scholars to participate in sit-ins, seminars, social media campaigns, and chai par charcha sessions.

Students are paying special attention to the reason why the BJP has brought up this issue. And like Agai, they are waiting to see if Modi will follow his words with positive action.

“We are already backward. Islamophobia has brought us to this point. We have seen the Jaipur train hate crime, the murder of Junaid and Nasir, and riots. We are facing exclusion,” says former student Aman Qureshi, who is active with DISSC.

As an active AISA member, Waqar too has taken up cudgels on behalf of the Pasmanda Muslim community of students. In his free time, he evangelises at other campuses on the importance of reservation. He calls it “informal awareness campaigning”. Waqar is critical of Modi’s decision to scrap the Maulana Azad National Fellowship on the grounds that it overlapped with other higher education schemes. It carried a monthly grant of Rs 25,000 for PhD and MPhil students from minority communities.

“Muslim women have been most impacted by the end of the fellowship. As per the current state of the country, they should be granted more reservation,” says Waqar.

Unlike Waqar and Qureshi, 20-year-old mass media student Shagufta Jabeen doesn’t host seminars or awareness programmes on Muslim or Pasmanda Muslim reservation. But even then, conversations she has with friends on the steps of Jamia Millia Islamia’s Central Library almost always circle back to this topic. Jabeen got a seat in the BA programme under the minority institute’s OBC Muslim quota.

“If this quota didn’t exist, I wouldn’t have got the opportunity to study. The same goes for my sisters,” she says. She wants all Pasmanda Muslims to have opportunities across institutions, just as she did, and not just minority ones like Jamia Millia Islamia.

“There are many underprivileged Muslim families who wish to educate their children. We are one of them. My father moved from Bihar to Delhi to educate us. Through reservation our dream came true,” says Jabeen, who wants to be a journalist one day.

The conversation is also slowly seeping into study circles at Delhi University even though it’s not a minority institute. At Ramjas College, a few study circles have started examining fee hikes and education schemes through the lens of reservation.

“Reservation is one of the centric issues in the student movement. These are issues related to students because they belong to this community,” says Abhigyan, a second-year political science Master’s student at Ramjas.

The Modi government’s stand in the Supreme Court was clear—reservation for Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians is unconstitutional.

Quotas for downtrodden Muslim ‘castes’

Others talk of a ‘quota within quota’ model.

Atif Rasheed, BJP leader and president of Nationalist Muslim Pasmanda Samaj, would like to see minority institutes do more for Pasmanda Muslims.

“Why does Jamia Millia Islamia not give reservation to Pasmandas?” asks Rasheed. Here, 50 per cent of the total seats are reserved for Muslims, with 30 per cent for the general category, 10 per cent for Muslim OBC and ST students, and 10 per cent for women. According to Rasheed, the 10 per cent reservation for OBC Muslims is not reflective of their population share. He wants institutes like Jamia to give 27 per cent reservation for OBCs.

By talking about Pasmandas, Modiji has acknowledged our identity. We have never even been mentioned by the Congress or other parties

-Hashim Pasmanda , grovery store owner in UP’s Mau

“Our share has been given to the upper caste,” says Rasheed.

This feeling of ‘second-class’ treatment by Muslims within their own community is something Pasmandas are railing against.

Hilal Ahmed, 34, works as a delivery person at a small cement shop in

Jamia Nagar. His family moved from Kanpur to Delhi 25 years ago. But nothing has changed. Ahmed and his brothers are also in the cement industry earning Rs 300 to Rs 500 per day.

“Even within the Pasmanda community some ‘castes’ are more discriminated against among the Ansaris, Saifis, and others,” says Ahmed who comes from the Gadheri community that traditionally relies on donkeys, mules, and horses for livelihood. “We are always told that we are equal. But if we are equal then why are we not given equal rights and opportunities?”

Rahul Gandhi’s catchy new slogan ‘Jitni Abadi, Utna Haq’— on the rights of a group in proportion to its population share—resounds and rebounds within the Pasmanda Muslim community.

In the Uttar Pradesh town of Mau, grocery store owner Hashim Pasmanda gazes at the pristine and large homes of upper caste Muslims like the Pathans, Sayyeds, and Sheikhs. Here the roads are wide and clean, a stark contrast to where he lives where drains are left open and the streets piled with garbage.

Hashim wants the Karpoori Thakur formula to be applied to reservation to ensure justice for these deprived groups. Named after the Bihar minister, it divides the OBC quota into Most Backward Classes and Extremely Backward Classes.

“The OBC reservation for Muslims should be divided between the most and extremely backward classes. Twenty per cent of the pie should go to the extremely backward,” he says.

Rahul Gandhi’s catchy new slogan ‘Jitni Abadi, Utna Haq’— on the rights of a group in proportion to its population share—resounds and rebounds within the Pasmanda Muslim community.

A new political awakening

The demand for Pasmanda reservation hasn’t ballooned into a big movement yet. This is because of a fundamental challenge within the community itself— the inability to acknowledge its own identity.

Based on his experience as an activist, the very members of the backward communities that Hashim is fighting for are not aware of their identity. “When I tell them that they are Pasmanda, they do not take it seriously,” he says in frustration. But he’s happy that the conversations are finally happening, for which he is grateful to Modi.

“By talking about Pasmandas, Modiji has acknowledged our identity. We have never even been mentioned by the Congress or other parties. This could narrow the gap between Pasmandas and the BJP,” says Hashim. The next step after Pasmanda recognition is reservation.

Much like what the Mandal Commission report did for the political rise of the Yadavs in UP and Bihar in the 1990s, the new push for Muslim reservations has clear political undertones.

There was a time in the 1990s when the movement for Muslim reservation was very powerful. The year 1994 saw a new demand for Muslim reservation with the creation of the Association for Promoting Education and Employment of Muslims (APEEM). It conducted its inaugural Convention on Reservation in New Delhi on 9 October, 1994, and supported “a separate quota for Muslims” over accommodation in the SC, ST, and OBC categories, according to a report published in 2014 by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS).

“But the movement does not appear to be as strong today. This is because the community is not organised. Organisations like All India Muslim Pasmanda Mahaz have for the time being kept this reservation movement alive,” says Khalid Anis Ansari, an associate professor of sociology at Azim Premji University.

The Kaka Kalelkar Commission, the Mandal Commission, the Ranganath Misra Commission, and even the Sachar Committee acknowledged caste-based discrimination among Muslims. The 2006 Sachar Committee report stated that the condition of Muslims in India is worse than SCs (Scheduled Castes) and STs (Scheduled Tribes).

The desire for reservations encompasses not just government jobs but also political representation. Much like what the Mandal Commission report did for the political rise of the Yadavs in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the 1990s, the new push for Muslim reservations has clear political undertones.

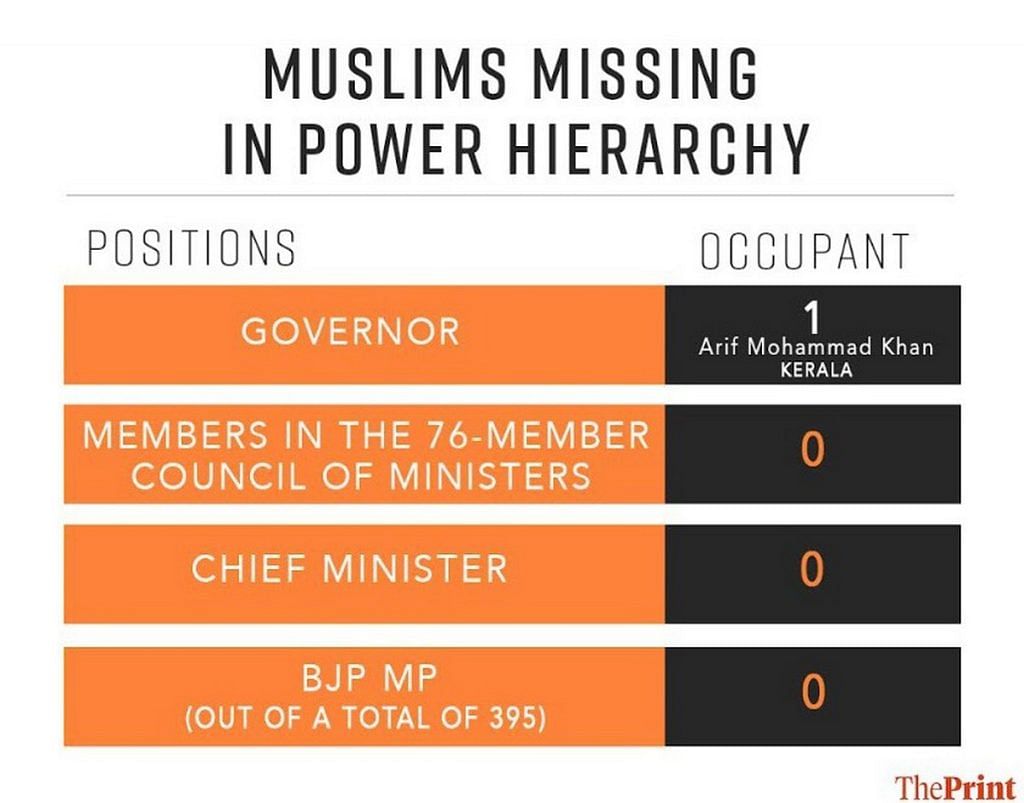

At present, no Muslim sits on a constitutional chair in the country, barring Kerala governor Arif Mohammad Khan. No Muslim holds a position in the 76-member council of ministers, and there isn’t even a single Muslim chief minister. With Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi’s resignation from the Rajya Sabha last year, the BJP has no Muslim among its 395 MPs.

But there is a reversal of this trend at the level of civic body elections. The 2022 Municipal Corporation of Delhi elections were a critical moment for Pasmanda Muslim politics when the BJP fielded four candidates from the community.

In Uttar Pradesh, during the local urban body elections in May this year, the Yogi Adityanath government fielded 395 Muslim candidates, with 90 per cent being Pasmandas. Sixty-one Muslims won the elections. In the previous urban body polls held in 2017, the party fielded 187 Muslim candidates, and two won.

According to Uttar Pradesh minister of state for minority welfare Danish Azad Ansari, the face of the BJP’s Pasmanda politics in the state, the upliftment of the community is a mission.

“It’s more than politics,” he tells ThePrint. “The opposition parties neglected this community when they were in power despite Pasmanda Muslims being core voters.”

Adityanath has also made overtures to Pasmanda Muslims through a few prominent appointments— Ansari as the minister of state, minority welfare and waqf department; Ashfaq Saifi as chairperson of the UP Minority Commission; and Iftikhar Javed as chairperson of the UP Board of Madarsa Education.

According to Ali Anwar, founder of the Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz, many Pasmanda castes, including the Halalkhors, Mehtars, Dhobis, and Mochis, should be given SC status.

He has made it clear that only those Pasmanda Muslim castes whose professions are similar to those of Hindu Dalits should be included in the SC category. According to him, these individuals are not “immigrants”, but Hindus who converted to Islam.

“In this country, let alone getting reservation on the basis of religion, there is discrimination against those who get it,” he says.

But the Modi government’s stand in the Supreme Court was clear—reservation for Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians is unconstitutional. Paragraph 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order 1950 mandates that anybody who is not a Hindu, Sikh, or Buddhist cannot be granted Scheduled Caste status.

Mohammed Tahir, a former member of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities, however, points out that this was done on religious grounds in the first place.

“Reservation for SC is based on religion. Granting reservation to Muslims based on religion is not unconstitutional,” he says.

A three-member commission headed by former Chief Justice of India KG Balakrishnan has been appointed to examine whether SC status can be given to Dalits from religions other than Sikhism or Buddhism

Meanwhile, in Maharashtra, former minister Arif Naseem Khan has tried to circumvent the religion issue. In June this year, he submitted a memorandum to Chief Minister Eknath Shinde demanding that 5 per cent Muslim reservation in education be reinstated based not on religion but on “economic backwardness”.

“In 2014, the Congress-NCP government issued an ordinance that granted a 5 per cent quota to the Muslim community on the basis of the (Narayan Rane) committee’s recommendation” Khan says. “But the BJP-Shiv Sena government came into power in the state in 2019 and halted the Muslim reservation. That’s why we are demanding reviving the reservation for Muslims.”

Taking quota call to villages

The demand for SC status by Pasmanda Muslims — and Dalit Christians as well—has caused some tension among Dalit groups.

Earlier this month, the Dalit Shoshan Mukti Manch, an umbrella organisation representing various groups fighting for Dalit rights, along with some Left-associated workers’ unions, lent their support to this demand. But many of the organisations also made it clear that this should not come at the cost of existing reservations.

Hilal Ahmed, associate professor at CSDS, delineates different aspects of affirmative action. First, identify which communities need positive discrimination, followed by a case-to-case examination.

States are expected to evaluate the progress of these communities after a certain amount of time. And, finally, there is the ‘exit policy’— after receiving a reservation for a certain amount of time, certain communities will leave to make space for new ones.

The debates and discussions, however, are limited to big cities and towns, campuses and study circles. It’s one of the reasons why Jamia Millia Islamia PhD scholar Lal Chand makes it a point to conduct awareness programmes on Pasmanda Muslim rights and reservation whenever he goes back to his village in Malda.

“When I go back to my village, I feel like I have gone back a hundred years,” says Chand. “And when I come to campus, I feel like I have come forward a hundred years.”