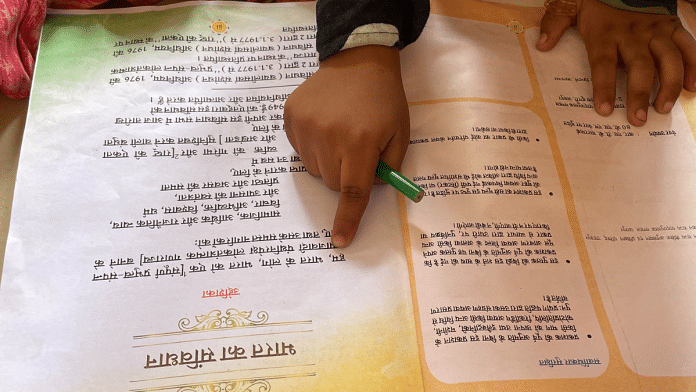

Jaipur: The little boy sits cross-legged on the bare floor of his modest two-room home outside Jaipur and moves his finger steadily across the text on the first page of his school textbook. He can’t read just yet. So, his sister reads it out to him. “Hum Bharat ke log, or We The People of India,” she says, reading out the first line from the Preamble to the Constitution. Six-year-old Abdul Rehman repeats after her.

It’s been just a week since his father, bangle-maker Mohammad Asgar, was shot dead on a moving train by constable Chetan Singh from the Railway Protection Force (RPF) in a chilling hate crime that killed two other Muslims. But the boy doesn’t know any of it. He doesn’t look up from his book. He can’t understand why so many visitors are milling around his home. The news of the killings has carpeted the lane with shock. Neighbours stand in clumps in different corners whispering to each other. Some student activists drop in bearing food and cash.

By now, everyone has seen the frightening viral video of the shooting, where Asgar is seen lying limp in a pool of blood inside the Jaipur-Mumbai Central Superfast Express train. And Constable Singh stands beside him, declaring to the Muslim passengers: “If you want to vote or live in India, I am saying Modi and Yogi are the two.”

The video has had a wrecking impact on Asgar’s family.

“I have seen the video of my husband’s killing. It keeps playing in my head. I have not shown the video to the children. They won’t be able to bear it. What was my husband’s fault? His identity? A beard?” asks Asgar’s wife, Umaisa Khatim.

The senseless and brazen killings on the train are part of the rising hate against Muslims in India that erupts as cow vigilantism or love jihad anxieties from time to time. There is also an alarming sense of pride accompanying these acts of murder — like Constable Singh exhibited. He was swiftly arrested and booked under multiple sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) — murder, promoting enmity on the grounds of religion, and kidnapping, among others.

A tale of tragedy

In the past week, Khatim has longed for a moment of solitude to let her tears flow freely. But she can’t find time to grieve with her five children—two under 10 years—wailing and fighting for her attention. She walks around the house listlessly, accepts condolences from well-wishers, lifts the children off the floor, and fights back her tears.

Her toddler, Rehman, never leaves her side. It is at night after everyone has fallen asleep, when Khatim cries silently, often covering her mouth with the pillow, she says.

The tragedy has pushed her into an endless and painful wait.

“In the morning, I look out of the window and keep staring at the street hoping for Asgar to return,” she says.

Khatim and Asgar moved to Jaipur’s Bhatta Basti from their hometown in Bihar’s Madhubani in 2022 to join the bangle-making workforce. They bought a machine, spotted a low-income basti of migrant workers like themselves, and rented out a home for Rs 6,000 a month, from where they made bangles while raising their children.

“Two rooms were something new for us. In Bihar, we lived in a hut made of bamboo,” Khatim says. While making bangles at home, Asgar would often gift his favourite ones to Khatim, she recalls.

This year, they dreamt of owning a mattress and bed, no longer wanting to sleep on the floor. So the family tried to save whatever they could from selling bangles, but the money just wasn’t enough. They were unable to pay the rent and were sliding into debt.

That’s when Asgar decided to give up bangle-making. He found himself a job as a sweeper in a mosque in Pune last month, delayed his dream of sleeping on a bed, and packed his bags.

He left for the train station that fateful day of 30 July. Seeing her husband standing at the door, Khatima got up to say goodbye— but the children kept tugging at her dupatta. In a hurry, she ran upstairs, opened her window, and managed to only wave at him. Asgar, with all his bags and baggage, walked down the alley, turning to look back at her from time to time. And then he faded into the distance.

At the railway station, he called Khatim to warn her that his phone was running out of battery. He would call after reaching Pune.

“He said I should take care of the kids and myself and make sure that Rehman goes to school every day. There was something in his voice that made me feel that he had a premonition of what was ahead for him,” Khatim says, rubbing her swollen eyes with her white dupatta.

Also read: Muslims in Nuh say sons being targeted — ‘he had gone for tuition that…

‘Genie out of the bottle’

On 8 August, the Borivali Government Railway Police (GRP) recreated the crime scene on the same train where Singh gunned down Asgar, two other Muslim men, and his senior officer assistant sub-inspector Tika Ram Meena on 31 July at 5 am.

A forensic examination confirmed that it was Singh who had made “hate comments” that could be heard in the video clip.

He fired 12 rounds from his automatic rifle while the express train was hurtling toward Mumbai. Asgar was Singh’s last victim.

The constable tried to flee after a passenger pulled the chain but was caught by RPF and GRP personnel near Mira Road railway station in Mumbai when the train ground to a stop.

The incident has been condemned by opposition parties. “The genie of hate is now out of the bottle and it will take a lot of collective effort to put it back in,” senior Congress leader Jairam Ramesh tweeted.

Singh’s mental health came under intense media scrutiny too. The Times of India reported that the constable used “to suffer abnormal hallucinations and was diagnosed with serious anxiety disorder”. But this was countered by a report from Mumbai’s Mid-Day: “RPF constable is of sound mind, hates Muslims”.

The constable, who is from Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras, doesn’t regret killing those people, Mid-Day reported. The hate crime has not been discussed in Parliament yet.

In the past week, protests have erupted across Jaipur. On 6 July, thousands of Muslims gathered in Jaipur’s Bhatta Basti and demanded compensation of Rs 1 crore for the family. Rafeeq Khan, Congress MLA from Adarsh Nagar, also joined the protests, urging the “central government to take strict action”.

The Ashok Gehlot government reportedly gave the family Rs 5 lakh as compensation. “Congress leader Mahesh Joshi visited us and the money was given by the district collector,” says Khatim.

But the aggrieved wife of the deceased is stricken with disappointment.

“What will Rs 5 lakh do? Ashok Gehlot has not given a strong statement. I have 5 children, and I have lost my husband, the breadwinner of my family,” she says. “The crime was committed by the RPF constable who is meant to safeguard us.”

Back in Bihar, the family used to vote for Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United), which was previously in alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). They’ve requested the Bihar CM to help them out.

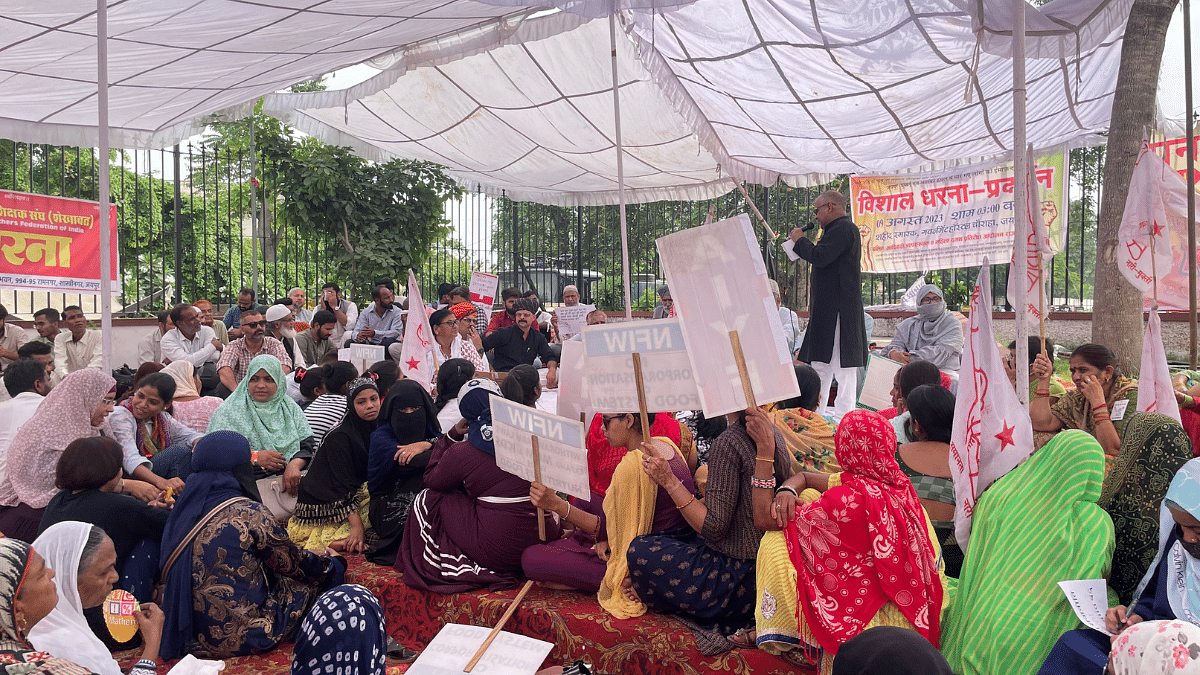

Not too far, a protest goes on opposite the police commissionerate’s office. Some activists and civil society members are chanting slogans and holding up placards reading “Darr se azadi haq hai hamara (Freedom from fear is our right)” and “Sampradiye taakate murdabad (Down with communal forces)”. Khatim’s sister, Raunak Praveen, is among them. More than a hundred people are demanding justice, freedom from hate politics, and the right to live in peace.

But the outrage and shock will dissipate with time, and Khatim knows that.

“People will soon forget,” she says. She wants the government to take responsibility for her four daughters and son and give them a house to live in.

“It’s just a week and my husband has already become a number for the government. Ek ginti ban gaye hai,” Khatim adds dejectedly.

Suspicion & fear percolates

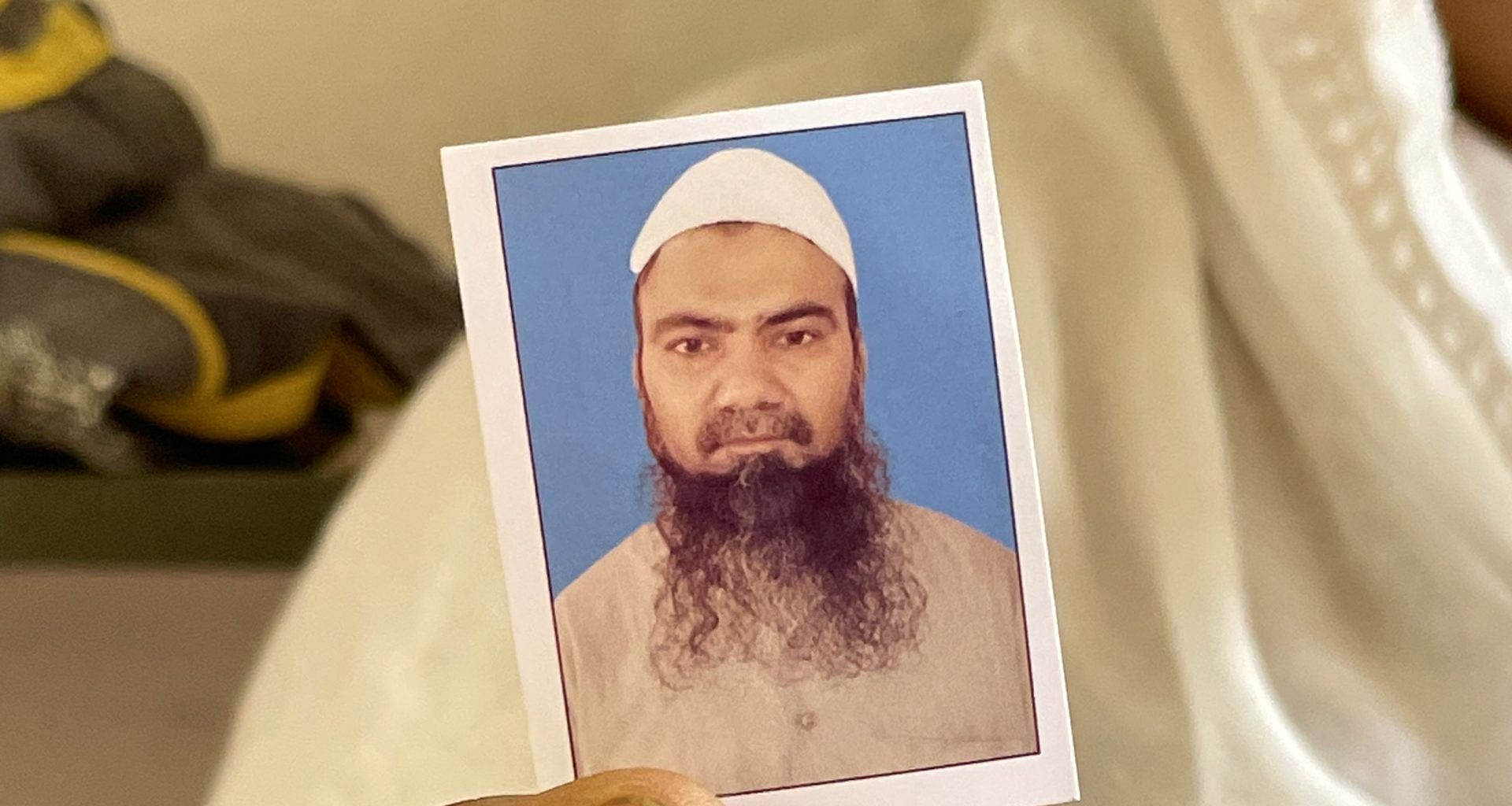

Khatim’s neighbours come and go — women wearing burqas in one room, men in another — to pay their condolences. Her father meets the men, holds their hands and hugs them. A passport-sized photo of Asgar is kept on the shelf next to the Quran. School textbooks and half-open potato chips packets are scattered on the floor. Children cry constantly.

Khatim’s elder daughter keeps cleaning the room after every two hours. Khatim tries to sleep while tossing and turning and often shouts, “What was his fault? He would pray five times a day”.

She vividly remembers how she was told about the tragedy.

On 31 July, Khatim had just served tea to her children when she received a call from the Mumbai Police. “Aapke pati ko maar diya gaya hai train mein (Your husband has been killed on the train),” the caller said. And Khatim broke down.

“I looked out of the window to find neighbours gathering outside my house. They had seen it on the news. My world shattered,” she recalls.

In just 10 days, Bhatta Basti has changed. The air is thick with suspicion and fear. Outsiders are stared at uneasily.

“If it can happen to Asgar, tomorrow, it can also happen to any of us. We can’t even trust the police now,” says Mohammad Farkuddin, a 63-year-old grocery store owner. He is interrupted by Mohammad Naeem, who is contemplating cutting off his beard. “I avoid going to the main city through shortcuts and narrow alleys. In the last week, I have only taken the main road. What if someone stops me and kills me on the spot? I can remove my beard,” Naeem says.

Khatim says she had heard of incidents of violence against other Muslims in recent years. But she told herself it must be because of a two-sided fight between Hindus and Muslims. But Asgar’s unprovoked murder has frightened her. The hate is closer than it earlier appeared to be.

With so many visitors coming to the family in the past week, Khatim is trying to protect herself. She has kept her Aadhaar card handy. Whenever someone asks her name or age, she pulls it out.

“It is better to show an Aadhaar card. You never know, tomorrow they might call us illegal immigrants because of our religion,” Khatim says.

Her eyes stray to the window.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)