New Delhi: At an event in a softly lit Delhi art gallery, featuring a conversation between historian Swapna Liddle and a guest speaker, most of the audience was left with just one question: Why didn’t Swapna Liddle speak more?

Halfway through the talk, the guest speaker — who wasn’t a trained historian — made a rookie mistake. The audience, made up largely of historians and students of history, held its breath.

Liddle gently interrupted him, corrected him, made a joke, and continued letting him speak. Her listeners lapped it up.

Swapna Liddle is the new toast of the town — Lutyens’ Delhi to be precise. She’s been everywhere in the past year. From book launches and exhibitions to conferences, her name is on every significant invite. She has exploded onto the scene and skyrocketed to a visibility that most academics don’t find beyond academic circles. And she has managed the trapeze artist’s act of speaking about history, openly and happily, without landing in hot water. At a time when history is a nuclear debate and historians are radioactive, Liddle approaches the discipline with aplomb.

Academic historians analyse and write about theories. But we need a public interaction — we need somebody who can engage with the public and educate them authentically with references – Rana Safvi, historian

She is a new kind of public intellectual: a visible historian and heritage conservationist who is actively engaged in her craft, and unafraid to show it. She conducts history walks across the city, posts regularly on social media, engages with the people in her comment section, and is a mainstay at any event about Delhi’s history.

She flits between spaces — both physical and intellectual — with ease and grace. Liddle is as much at home in air-conditioned Khan Market cafes as under the blazing sun while pointing out obscure inscriptions on monuments.

Her calendar is blocked full: in a matter of one week, she spoke at a book club in Gurugram, sat on a panel with historian Ira Mukhoty at the Kathika Cultural Centre Haveli in Old Delhi, addressed schoolteachers at a ‘History for Peace’ conference in Coimbatore, and hosted a conversation at the aforementioned art gallery. It’s a busy life for a historian.

Her popularity is both because and despite the fact that she’s not in academia. Not being tethered to the demands and expectations of a university allows her to dedicate all her time to the pursuit and protection of history as a discipline, with her academic background serving as a stamp of authenticity.

I stick up for what I think is history — history and politics do intersect, but not in the way most people think. I try to speak through history. Of course, I also have the luxury of not being constrained, and that helps – Swapna Liddle, historian

“Public intellectuals usually take up extremely urgent, very narrowly political issues and comment on them,” said historian Tanika Sarkar, who taught Liddle while she was an undergraduate student at Delhi University’s St Stephen’s College in 1989. “But Swapna’s kind of public history also stirs the imagination and makes us see those times in a tangible, vivid, sensuous way. She’s able to go against the current climate of opinion and yet not get bogged down by polemic — all the while still presenting history in a way that everyone can respond to.”

And no one else does the kind of work she does possibly because no one else has tried yet, said Liddle. She has both privilege and time on her side. She dismisses the suggestion that she’s on her way to becoming the next Romila Thapar.

“No way! Romila Thapar is an intellectual!” she said, laughing. “I don’t pretend to be anywhere near that level, and moreover I would hate to be in that position — to be put on a pedestal and seen as untouchable. I don’t take myself too seriously!”

Also read: ‘Leave rewriting history to historians’ – says Swapna Liddle at her book launch

History over politics

Swapna Liddle wants a break from heritage. It’s conversations around heritage conservation that cause her anxiety and stress, not history.

It’s a task because she’s most often associated with heritage conservation: her career in the public arena took off with her heritage walks, which she began doing in the late 1990s and then continued while she worked at the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). It’s also what kept her interest in history alive. Conducting the walks and training walk-leaders was a sizable portion of her job at INTACH, where she served as co-convenor from 2006 and convenor from 2016 to 2021. She’s no longer attached to it but still does around one to two walks a month.

“Advocacy is an important part of INTACH’s mandate, and that pressure does build up. But as a voluntary organisation, there’s only so much you can do,” said Liddle. “In my personal capacity, I felt I wasn’t making the kind of impact in this area that gave me satisfaction. My energies and talents could be better spent elsewhere, where I have a bit more impact. Writing does give me more satisfaction, and I continue to do heritage walks” she added.

And there’s a sense of exhaustion when she talks about the complexities of heritage management, possibly stemming from years of running up against government machinery. She smooths her silver-grey hair, always pulled back from her face, pausing before making her next point.

What does bring her satisfaction is interacting with history in a tangible way. Liddle takes out her phone and scrolls through her cover photos on Facebook, going back years. Visuality is very important for her: it’s what helps bring history alive, however limited.

“It’s an accident that I started doing this,” she said, referring to the heritage walks that eventually translated into her own professional niche. “And I realised that to talk to people who did not necessarily have a background in history I needed to speak in language they could understand. I got used to using simple language, and that tone and tenor also translated into my writing.”

Her accessibility is what has cast her in the role of a public historian and not an academic historian — someone who’s visible on the field and not just in an ivory tower.

“Academic historians analyse and write about theories. But we need a public interaction — we need somebody who can engage with the public and educate them authentically with references,” said historian Rana Safvi, adding that Liddle’s informative posts on Facebook and Instagram bust myths. “The role she plays is informing the public, and an informed public makes correct decisions.”

In 2016, Liddle began posting a photo every week on her Facebook page with a caption explaining its context — from old photos of the Yamuna to paintings of the hidden areas of Delhi. It wasn’t the kind of material that would go viral, she said, but content that would spark a conversation.

No way! Romila Thapar is an intellectual…I don’t pretend to be anywhere near that level. And moreover I would hate to be in that position — to be put on a pedestal and seen as untouchable. I don’t take myself too seriously – Swapna Liddle, historian

And that’s the most important part of Liddle’s practice as a historian: to engage with others. It’s not just about engaging with the past, it’s about inviting people to participate in how the past connects to the present.

But she’s walking a tightrope too: the history of Delhi is inherently political, especially as layers are constantly peeled back to expose different aspects of a contentious past to fit newer narratives. On her walks, she tries to point out syncretism in the way Delhi has developed. But such insights have fewer takers today — while history is nuanced, people prefer to see things in black and white.

“One fallout of being somewhat in the public eye is that there is a temptation to comment on things one is not competent to speak on. For instance, sometimes journalists ask me to comment. I’m wary of making offhand comments in such cases—because I’ve seen the damage it can do,” she said. “Anything I say I have to take responsibility for.”

According to Liddle, stalwart historians such as Romila Thapar and Irfan Habib are considered “establishment” academics, though in a context unlike today’s. Academics today are sometimes compelled to protect their jobs, and therefore might shy away from making public statements, she said.

“I stick up for what I think is history — history and politics do intersect, but not in the way most people think. I try to speak through history. Of course, I also have the luxury of not being constrained, and that helps,” she said, referring to the fact that as an independent scholar, she’s not tied to an institution like a university.

Liddle’s inquiry into the past — like any other historian’s — is independent of her personal feelings. What she finds in the past doesn’t affect her politics, she said. If she finds bigotry, she’ll talk about it. If the past was “crappy”, she’ll tell you about it.

“I will never set out to write a book to refute something. I start out from a point of curiosity and, I hope, with an open mind,” said Liddle. “No one who is a serious historian will write things with a set political agenda, though of course, our politics does determine which question we are interested in, which avenues of enquiry we take up. As for my style of writing, I prefer a narrative style where I let things unfold. I present facts to the readers and encourage them to come to their own conclusions.”

Historians who look to flatter or appease a political narrative can’t be serious historians, though nobody who thinks critically is apolitical, she said.

“I want to separate history from the identity politics of today,” she added earnestly.

The question of whether this is truly possible — especially with Delhi’s layered history as her subject matter — hangs in the air.

Also read:

A continuing passion for the past

Liddle never disconnects from history. History adorns the walls of her home, in a posh residential part of South Delhi. In the foyer of her home, right by a winding staircase with iron balusters, an Urdu couplet by poet Mir Taqi Mir catches the eye:

Dilli ke na the kuche, auraq-e-mussavir the, jo shakl nazar aayi, tasveer nazar aayi. (The lanes of Delhi weren’t just that; they were pages from an artist’s album. Every face that one saw was like a painting.)

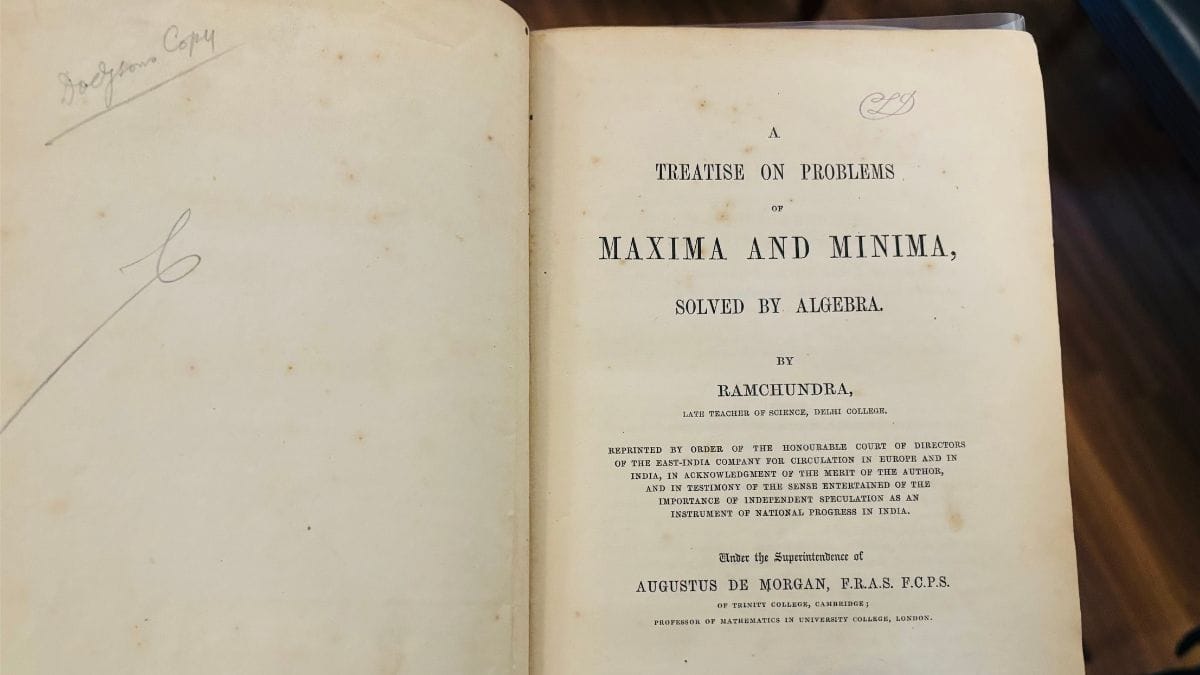

It’s a sentiment Liddle lives by. And it’s reflected in the old photographs and prints of Delhi that are both proudly displayed on her wall and carefully stored in wooden armoires. Even her hobbies include collecting old photographs and books. A prized possession is an 1859 first edition of Indian mathematician Ramchundra’s Treatise on Problems of Maxima and Minima, which was owned by 19th-century English author Lewis Carroll.

It’s a hobby she shares with her husband, advocate Gourab Banerjee. Even her sister, Madhulika Liddle, writes historical fiction. It’s so much a part of her private and social life that she never seeks to escape it.

One fallout of being somewhat in the public eye is that there is a temptation to comment on things one is not competent to speak on. For instance, sometimes journalists ask me to comment. I’m wary of making offhand comments in such cases—because I’ve seen the damage it can do…anything I say I have to take responsibility for – Swapna Liddle, historian

And she never gets tired of history either. The exhausting process of engaging and educating isn’t daunting to her. And she’s not scared of a fight — even if she doesn’t see it as one.

“At this point of time, a public-facing historian like her is very important,” said Safvi. “Swapna’s demeanour is also calm and knowledgeable, which is why people accept what she’s saying. Even when I see her in arguments, she answers all questions with great patience.”

Liddle’s books are written in the same way she speaks: pleasant, persuasive, peppered with personal anecdotes. Her eyebrows knit together when she points out a contrarian observation about the past — right before breaking into a laugh, inviting her listeners in on a joke even if they don’t catch the full import.

She’s been a student of history her whole life. After graduating from St Stephen’s, she immediately enrolled at Jawaharlal Nehru University where she did her Master’s in 1991 and her MPhil in 1995. She dropped out of her PhD programme at JNU when she became more involved in her family life, and re-enrolled at Jamia Millia Islamia in 2000. It took her seven years to finish her PhD, soon after which she started working with INTACH. Her heritage walks and writing continued as well, giving her the space and time to develop her voice as a historian.

This voice, Liddle said, is independent of her political position. She has a problem with terming Mughals “invaders,” for example. It’s inaccurate.

“It’s more accurate to say that they’re ‘conquerors’ — or rather, Babur is a conqueror. It’s different from being an invader because at the time conquest was a legitimate form of regime change, far before the dawn of modern democracy,” she said.

“The Mughals” as a whole is a deceptive category, as their reign spans centuries and can’t be painted with the same broad brush, according to Liddle.

She pauses for a moment. “Plus, calling them “foreign invaders” wouldn’t be accurate as they soon became “Indianised” in as many senses of the word. You know?” she asked, right before breaking into a laugh, the dismissal of an entire ahistorical argument dissolving into her laughter.

“My position is that this idea is often extended to call out all sorts of slurs on Muslims and that is something I abhor,” she said. “But I don’t need history to justify that the Mughals were great guys in order to support my political position today — which is that everyone who lives in this country has equal rights and deserves to be treated as such,” she added, firmly.

Liddle’s political position, she said, is that history should not be used to justify political positions today. She can read history for what it is — and if those truths are uncomfortable, that’s alright, she stressed.

“She is a public intellectual also because in the current situation anything that Muslims have achieved is dismissed very cruelly and is being rapidly erased from public memory — whether textbooks or names of spaces,” said Sarkar. “She makes that history very vivid, and human in a sense. It keeps its values alive.”

Also read:

Defending the discipline

An entire wall in Swapna Liddle’s home — which she calls the ‘Delhi Wall’ — is adorned with old photographs and paintings of the Indian capital.

History is important, particularly because so many ahistorical claims are being made to serve political agendas – Swapna Liddle, historian

This visuality translates easily to her social media, which has also really boosted her reach and visibility. But she’s only really interested in Instagram and Facebook — X is for angry reactions and hot takes, she said. What sets her apart from her peers is that she’s cordoned herself off within Delhi, but has emerged as a defender of the profession online.

“I want people to stand up for history as a discipline,” she said. “A fundamental issue today is the deliberate discrediting of history as a discipline. Often the argument made is that we cannot read what trained historians write because they do not write in an easy-to-read style. I think that is unfair,” she said.

She pointed out there are several historians who do write in an accessible style — and that no one is saying scientists need to write more accessibly for science to be taken seriously.

“At the same time, historians cannot afford to ignore writing on historic subjects by those who may not be trained as historians but have great influence and are widely read. There has to be engagement on both sides of the academic divide,” she added.

Part of her mission to defend the discipline is ramping up her own projects. She understands that social media hasn’t just changed our consumption of history, it’s changed the very aesthetic value attached to heritage — which is where photographs come into play, especially among young people as they explore the city.

“What is of greatest importance today is that you can take a pretty picture of something,” she said.

Building a democratic digital archive, accessible to all, is one such project. Starting a podcast is another — not a podcast, she said, quickly correcting herself, but a live stream with a way for viewers to comment and ask questions. It’ll create more engagement.

“History is important, particularly because so many ahistorical claims are being made to serve political agendas,” she said, suddenly serious.

She hopes her trajectory can be a model for others. Historians don’t always have to stay locked up in their ivory towers, they can work in adjacent spaces as she has done. The History Collective is part of this endeavour to encourage people to occupy space in heritage, advocacy, and other such areas.

“There are not enough historians here,” she said, referring to the heritage field in particular. “I can’t think of too many people in similar positions, who are trained as historians and now seek out other fields,” she added. “Perhaps they haven’t tried.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Delhi’s obsession with Mughals is extremely parochial. Mughals being conquerors is not a justification for torture and forced religious conversions. Which is not something all conquerors did incidently. The Graeco Indian kingdoms did not land up trying to eradicate Indian gods. Mughal impact on the rest of India is either that of killers and usurpers or neglible. No one wanted them here. So why celebrate them? It comes from a primal Delhi instinct to associate with victory and forget that they surrendered to conquerors repeatedly. The rest of India does not carry this guilt.

Fke news peddler Couptaji, his equallt demented side kicka at print and their obsession with invaders and killers like mughals.. laughable and pathetic.

No one cares for your mughals or your slavery to islamic invaders. Get a life . Remember what happened to sikh gurus by these so loving mughals