Panchkula: Tushar Kaushik from Panchkula wants to save India from communalism, socialism, and cronyism. And his answer is the Libertarian Party of India—with all of six core members.

With his thick frames, crew-cut hairstyle, and quiet demeanour, Kaushik, 27, is not your typical neta. His podium is podcasts and posts on social media. His ‘office’ is a utilitarian co-working space. But in the year since he launched the Libertarian Party of India (LPI) in 2024, it has acquired nearly 14,000 followers on X alone—Indians like him, fed up with the government’s bureaucracy, high tax rates, caste politics, and intrusion into their personal lives.

“The year 2024 was the moment I had realised it had gone too far. The increases in capital gains tax, the Ladli Behan Yojna (women welfare scheme) and other socialist schemes—the country was moving in the wrong direction,” said Kaushik.

The Libertarian Party of India doesn’t have the financial muscle of the Bharatiya Janata Party or the historical legacy of the Indian National Congress. But disillusioned Indians are increasingly drawn to the LPI’s principles of free markets, deregulation, and individual liberties. With its reels and podcasts discussing everything from freedom of speech to property rights, the new party is gaining traction. Run like a tech startup, it has no official headquarters and is entirely self-funded.

“We are staring in the eyes of communism,” said Kaushik. He doesn’t pound the table with his fists or raise his voice for effect like a seasoned orator. “The concept of private property is being eroded. And this will keep escalating.”

If all goes as planned, he will register LPI with the Election Commission, field candidates, and take on Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi.

In the future, 40-50 per cent of our population will reside in urban areas. Issues of low taxation, deregulation, ease of doing business become relevant when the population becomes urban. Our bet is on this, and that’s why we are starting ahead of the curve

-Tushar Kaushik, founder member of the LPI

India has flirted with libertarianism before, but it was a different country then. In 1959, C Rajagopalachari launched the Swatantra Party as a counter to Nehru’s socialist policies. For four years from 1967 to 1971, it was the single largest opposition in the Lok Sabha with 44 seats. But by 1974, it had completely dissolved.

But this is not the naive, newly independent India. People are hungrier for change.

Kaushik is aware that for LPI to succeed, it will have to show a clear alternative to the Nehruvian socialism that still defines much of India’s politics. This time, he says, things will be different. The reach of social media will revive the movement.

His dreams for LPI may seem idealistic, even far-fetched. But don’t discount the power of a multi-party democracy, said Kumar Anand, a senior fellow at the Centre for Civil Society, a New Delhi-based think tank.

“Here, you don’t need 51 per cent of votes to win an election. Even with a 2-5 per cent vote share, you can make or break someone. Be the king maker.”

For many of LPI’s social media followers, the party needs to move faster. “Why is this party not taking steps necessary when India desperately needs a 3rd front!!?????” asked one X user.

Also Read: Let’s talk about red tape, cash flow, say Indian startup founders

Capitalism, chainsaws, and new converts

Kaushik began the decade by embracing Narendra Modi’s ‘Minimum Government, Maximum Governance’. By 2024, he was so disillusioned by the failed promises that he didn’t vote for any party.

The LPI’s first physical meeting, painstakingly organised by Kaushik in Gurugram this March, was an eye-opener: there were others like him. Over 40 members attended the first Indian Libertarian Summit, held at Innov8 DLF Cyber Green, a co-working office space.

Earlier efforts to fight socialism came from India’s elite — the political and royal classes. Today’s libertarians are a different breed. They’re mostly SIP-funded, middle-class, and raised on Manmohan-era economics. Not elderly businessmen with decades to hone their disillusionment, but 20- and 30-somethings, fed up with the status quo and raring to change it.

“We had members fly in from Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Pune,” said Kaushik.

Representatives from the Spanish and US libertarian parties also addressed the audience via video conference. What was earlier discussed exclusively online, now had a physical space to grow.

“The Libertarian Party has now become a part of our [India’s] history,” said Kaushik.

In the backdrop of the podium at the Gurugram event, an image of Argentina President Javier Milei holding a chainsaw loomed large. It’s a viral visual symbolising his slash-and-burn approach to state regulation and public spending, later appropriated by Elon Musk during his DOGE cuts.

“In the future, 40-50 per cent of our population will reside in urban areas,” said Kaushik, who was dressed for the occasion in a grey blazer, glasses tucked away. “Issues of low taxation, deregulation, ease of doing business become relevant when the population becomes urban. Our bet is on this, and that’s why we are starting ahead of the curve.”

One after the other, speakers defended capitalism, complained about government overreach in their businesses, and railed against “socialist practices like the upcoming caste census”. This, they argued, was not the government’s job.

What was earlier discussed exclusively online now had a physical community willing to come together.

Buoyed by its success, Kaushik is now gearing up for the next physical meet in Mumbai on 24 July.

“We will discuss the 1991 market reforms,” he said, adding that the group wanted to celebrate India opening up its markets and bringing in reform. But he isn’t just relying on offline meet ups to increase membership.

The party also runs a social enterprise accelerator program, a Substack, and an online ‘gurukul’ called Heroes of Freedom for educating the public on libertarian ideology.

“We have a ten-year roadmap,” said Gurugram-based party member Ashutosh Singla, one of Kaushik’s school friends. They plan to conduct classes to train volunteers to spread the word. “This includes teaching them oration and convincing skills.”

A long list of talking points, taxes to temples

For many of LPI’s social media followers, the party needs to move faster. “Why is this party not taking steps necessary when India desperately needs a 3rd front!!?????” asked one X user, replying to a post about building a society around “individual liberty, rights, and responsibilities in all spheres of life. Social, Economic, Political, Spiritual.”

Some issued a challenge. “You’re BJP without Hindutva. So anti-interventionist against invaders on our own soil?” asked one sceptic. The reply: “No anti-government intervention in economy or culture. Not security.”

Here is the Plan of Ascension.

1.)Organize all the honest, productive, independent minded people of our country by reaching out to them virtually and physically.

2.)Spreading the message of liberty to those seeking relief from tyranny of injustice, bribery, intervention.

— Libertarian Party of India ?? (@libertypartyind) March 28, 2024

The party’s X handle is sprinkled liberally with libertarian catchphrases. Pro free market, pro freedom, anti bureaucrat, anti reservation. It also adds “pro Indic civilization”. The bio signs off with a hashtag: #freeordie.

LPI’s website is peppered with articles on tax freedom, critiques of election freebies and censorship, the right to data privacy, and a host of other libertarian talking points. But it’s the official party manifesto, the most viewed post, that stands out.

It opens with a bold claim: “The British never left, they merely left their replacements in charge.”

In the middle of a lunch of parathas and curd, Kaushik whips out his Samsung phone to display a YouTube video on Switzerland.

“We propose decentralisation, ideally like Switzerland,” said Kaushik, pointing to how the landlocked European country has power distributed amongst all 26 cantons, each with their own set of tax laws and parliaments. “This way, even if someone crazy gets elected at the centre, it’s essential the system has strong municipalities and villages to counter this.”

Kaushik has help from a six-member inner circle, who are building the party brick by brick. One of the oldest members, a veteran of the ideology, is 42-year-old Ajay Mallareddy from Hyderabad.

The two met just over a year ago on libertarian forums — safe spaces for innumerable young men, and a handful of women, to openly debate India’s tax policies, economic reforms, infrastructure, and property laws.

Some people eat pork, some eat beef, some don’t eat at all—it’s fine, to each their own. The whole point of individual liberty is making choices that are comfortable and convenient to you without infringing on others

-Ajay Mallareddy, in a video posted on X

Mallareddy has been a libertarian for over 25 years. Growing up in the ’80s and early ’90s, he grew fed up with government corruption and inefficiencies, which led to a strong belief in private sector participation.

“I remember applying for a simple phone connection was such a tedious process,” he said. The cell phone revolution made him value the greater role the private sector could play. “My first bank account was with ICICI and there was a world of difference between that and other government banks.”

In 2012, he stumbled on a Facebook group for Indian libertarians, which served as an entry point to discuss the ideology within the ambit of the Indian political landscape. The deep discussions and long form posts shaped his decision to transform an interest to a serious occupation.

Mallareddy ran a software company for a few years before opening a restaurant business. Now, most of his time goes toward LPI and an advocacy group he runs, called Center for Liberty (CFL). He focuses on producing content to spread libertarianism. This ranges from creating regional content in Telugu, producing videos about free markets, and publishing economic reports and policy papers. CFL is currently working on a report that argues for extending business hours in cities.

“We are hoping to convince the government to let businesses run late in the night – this increases economic growth and even makes areas safer,” he said.

Together, Mallareddy and Kaushik conduct AMAs (Ask Me Anything) on LPI’s X handle, where they tackle current issues through a libertarian lens, in the hope of appealing to a wider audience.

In a 22 May AMA, when asked his view on halal, Mallareddy said he didn’t see it as “unlibertarian.”

“Some people eat pork, some eat beef, some don’t eat at all—it’s fine, to each their own. The whole point of individual liberty is making choices that are comfortable and convenient to you without infringing on others.”

He added that a libertarian society would be “great for anyone who wants separation of religion from the state”.

“Not a single Hindu temple would be under the control of the government. Let temples be free, let mosques be free, let churches be free.”

It was Rajaji, founder of the Swatantra Party, who coined the expression ‘Permit-Licence Raj’ to signify how the new system was as ‘intrusively tyrannical’ as the British Raj it had replaced.

From Lucknow to libertarianism

Kaushik’s sparse shelf straddles sci-fi, economic history, and contemporary philosophy—books that have moulded his ideology. Frank Herbert’s Dune jostles for space on his bookshelf with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus.

“I liked Robert A Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” he said. He finds parallels with its anarcho-capitalist society and the utopia he dreams of for India.

Kaushik jogged his memory to trace his earliest influences. His thoughts jump from his schooling across the country to Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson, Argentina President Javier Milei, and even the fictional Ron Swanson from the American sitcom Parks & Recreation.

“Milei proved that in a democracy, people are willing to give a chance to alternatives when they are fed up with the status quo,” said Kaushik. In 2023, Milei won on a platform of tackling corruption and cutting government spending.

Kaushik was born in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, but his father’s government job took the family to Jind in Haryana, Shimla in Himachal Pradesh, and finally Chandigarh, where he completed a five-year integrated degree in social sciences from Punjab University in 2021. His earliest ideological influence, though, came from a Dayanand Anglo-Vedic school in Jind.

“The school promoted Indic values about respecting our culture, rather than looking down on it,” he said.

The common thread between this and his ideology was decentralisation, he added: “Just like in our culture there is no one God. Every household follows its own form of worship.”

American economist Thomas Sowell, Jordan Peterson’s dissection of communism, and the policies of Singapore’s former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew left their mark as well.

Throughout his life, Kaushik dabbled in ideas and ventures, mostly through collaborations with friends. Some were informal, like an all-male secret society he formed on Telegram in 2022, two years before launching his political party.

“It was called the Free Man’s Republic. We mainly shared ideas and supported each other,” he said, laughing. But this desire to ideate and collaborate problems on solving pain points took more formal shape over time.

He ran a slew of startups, from a healthy food delivery service during college (“students don’t have purchasing power”) to opinionez.com, a volunteer-led news portal where guest writers would debate both sides of a topic. Most of these ventures didn’t take off the way he’d hoped, but that didn’t slow him down. A mindset shift came during the pandemic, when his ideology began to crystallise.

That entrepreneurial streak and refusal to be boxed in runs in his family. His father may enjoy the perks of government service, but once he retires from his post in Mumbai, he wants to build an energy-independent village, powered by solar panels and biogas from the local gau shala (cow shelter).

“In India, all parties are socialist in their economic policies. People will eventually look for someone who is doing the opposite, going against the status quo,” said Kaushik.

Frustrated with red tape, compliance, and convoluted tax laws, some entrepreneurs are also turning to LPI for hope.

Legacy of a lost party

India’s tryst with libertarian ideas isn’t new. It has seen fits and starts. But Gandhian socialism is so embedded in the political psyche that libertarianism has rarely found much currency. The default mode continues to be socialism even after three decades of economic reforms.

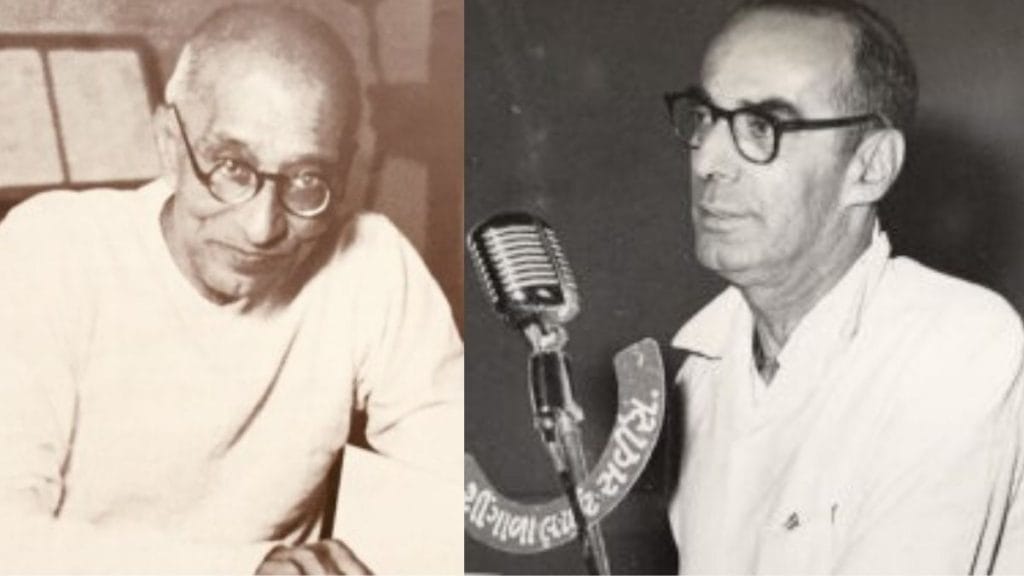

Some former Congress leaders tried to push back. Through the Swatantra Party, C.Rajagopalachari (‘Rajaji’), Minoo Masani, and NG Ranga challenged Nehru’s socialist policies. They warned that socialism was taking the Indian economy down a dangerous path — and people were listening.

The party gained significant traction, particularly during the 1962 and 1967 general elections when they won 18 and 44 seats respectively in the Lok Sabha.

“The reason the Swatantra Party was started was in opposition to the Nehruvian idea of socialist policies across sectors, including collectivising agriculture,” said Anand. Rajaji and Masani had initially accepted some aspects of social planning, but Nehru’s more extreme moves changed their minds. The SP leaders wanted checks on the stranglehold of state socialism.

The party’s legacy includes working with Charan Singh to sink the idea of collective farming in India.

“One should never forget the fact that the Swatantra managed to prevent a national calamity. In the glorious Soviet Union and People’s Republic of China, the forced collectivisation of agriculture resulted in the deaths of millions of people in each of those fraternal socialist countries,” wrote entrepreneur Jaithirth Rao for ThePrint.

It was Rajaji who coined the expression ‘Permit-Licence Raj’ to signify how the new system was as ‘intrusively tyrannical’ as the British Raj it had replaced.

As the idea took root, the Indian Libertarian, a fortnightly journal, was first published in 1957. A 1959 issue criticised the country’s tax system, lamenting that ‘heavy taxation and regimentation have brought the country to bankruptcy’. The publication shut down in the early 1980s, around the time the ideology was losing steam in India.

In 1971, the Swatantra Party joined a coalition formed to defeat then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, but fared poorly, winning only eight seats in the Lok Sabha. The following year, Rajaji died, and the party’s fortunes collapsed.

“Criticism has been levelled against the party that its ideas didn’t resonate with people,” said Anand. The Swatantra Party, he added, was even called the ‘Maharaja Party’ since several heads of princely states, including Gayatri Devi, joined it.

The SP party may have fizzled out, but the ghosts of their libertarian ideals never quite vanished. Members of the Libertarian Party of India argue that the time is ripe for change. The political landscape has changed dramatically. In the decades after gaining independence from the British, Indians saw the State as a saviour. But that trust has eroded. Taxpayers today are increasingly frustrated with government services, from healthcare to education.

“Back then, people didn’t have a frame of reference and were too caught up in Nehru’s socialism,” said Mallareddy. It didn’t help that literacy was low and that getting contrarian ideas across was difficult.

“If you had to disseminate information, it had to be via the radio or traditional print media, which were very tightly controlled by the government,” he added.

Also Read: Swatantra Party had a lot to say on China after 1962. If only Nehru had heard them

Pitching to the startup crowd

Kaushik, Mallareddy, and other libertarian colleagues cannot be accused of elitism. They are your Everyman, fighting licence raj on the ground. And they aren’t just attracting academics and philosophers. Frustrated with red tape, compliance, and convoluted tax laws, some entrepreneurs are also turning to LPI for hope.

“My own trademark, filed by an attorney, has been rejected seven times,” said Singla, one of LPI’s members who works in the publishing industry. “Our funder ID — required to receive sponsorship for publishing research papers — has been delayed for three years.”

LPI hasn’t yet registered with the Election Commission of India, but Singla claimed that the process is in motion. This includes submitting a list of at least 100 members, an affidavit, and public notices in newspapers, among other requirements. But Mallareddy made it clear that LPI won’t be following the same playbook as other parties.

“Our position is we won’t lie to get votes. If people don’t vote for us, it’s unfortunate—more so for them,” he said, adding that it was imperative the public understood libertarian ideas before supporting the party.

The fact that LPI hasn’t started fielding candidates and faces the prospect of coming up against larger regional and national parties with deeper pockets doesn’t faze him.

“We are the bitter medicine, the inconvenient truth for this country,” said Mallareddy.

Udit Hinduja is a graduate from the inaugural batch of ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Infinite thanks to the author and The Print for publishing this article.

Like all good things, this too shall perish. India gets anaphylactic shock at the mention of free market.

Libertarianism is the ultimate BS pursued by man-children who haven’t moved past the college Ayn Rand phase. Yes, it is primarily men. This idea of man being an island and “doing it all on his own despite society” is very seductive, but ultimately bogus. These individuals should move beyond labels and understand how the world truly operates.