New Delhi: Archana Sharma was the only Indian scientist at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, who was involved in the 2012 discovery of the Higgs Boson – a missing puzzle piece that completed our understanding of the fundamental forces and particles in the universe.

But back in India, not many people understood the significance or the broader implications of the particle physics research — thus Sharma decided to take it upon herself to dedicate time to science communication.

Travelling to government schools in remote parts of the country, Sharma interacts with preteen students — diligently explaining not only the fundamentals of physics but also teaching them how to sift through the huge CERN database to look for Higgs Bosons while sitting in their homes.

The strength of Indian scientific talent and institutions is an established truth. But what India has lacked over the years is public science. Many have called out the successive governments for not promoting science as a people’s movement and encouraging scientific temperament. India just didn’t have science communicators. Now, that is changing. From blogs to podcasts to YouTubers, more and more people are moving their focus to jargon-free communication and promoting public engagement with science.

However, as the number of science communicators in India increase, who should bear the cost of the work is a burning question that many professionals are still trying to figure out.

Not all of those in the field are scientists. A Bangalore-based techie moonlights as Gareeb Scientist on YouTube. Preferring to only be referred to as GS, he creates videos about ISRO’s rocket engines or semiconductors for fellow geeks and nerds.

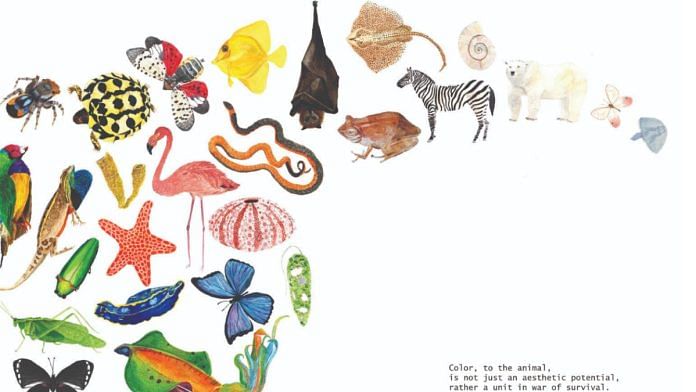

With a PhD in biological sciences, Ipsa Jain is taking a more colourful route to popularise the subject. Instead of just relying on words, Jain uses art to visualise what people may have never seen – from microscopic cells to explaining how ideas turn into experiments in the lab.

Jain, Sharma, and GS are part of a diverse and growing community of people who are passionate about taking advanced scientific knowledge outside the confines of the lab and making it accessible to the public whose taxes fund much of the research.

Traditionally, the way that scientists communicate their findings is through research papers published in scientific journals. However, this is limited to their peers and others who understand the complicated jargon used.

The public — which stands to benefit or be affected by the work — remains largely oblivious to what goes on in science laboratories.

Science communicators try to bridge this gap through more accessible media — newspapers, videos, podcasts —in jargon-free language.

While Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson have been lauded for making science more accessible to the Western audience through TV shows and books, in India most scientists have not been comfortable enough — or motivated — to popularise the subject.

HS Sudhira of research collective Gubbi Labs points out that at least 20,000 to 30,000 papers get published every year — out of which last year the collective was able to communicate about just 250.

“So much of the research in India never gets written about,” he said.

Also Read: World’s oldest carbon-dated banyan tree in UP has a structural problem. But faith guards it

YouTubers to illustrators

During his PhD days at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru, Sudhira was part of a team looking for frogs in a village near Sirsi, Karnataka when they encountered a curious villager who asked the team why they were loitering around in the fields.

When the researchers explained, he was taken aback. He found it very difficult to understand why the government was paying — and even providing a jeep — for its employees to watch frogs.

The encounter got him thinking about the dissonance between what was happening at IISc and what people outside the campus knew.

Then in 2013, eight years after the meeting he crystallised his individual efforts into Gubbi Labs.

Since the team at CERN discovered Higgs Boson in 2012, Sharma has been intrigued by the way Europe and the rest of the world communicated scientific discoveries to the public.

I wanted to take this experience back home to India, particularly to those who do not have the means,” she said.

She regularly takes part in science festivals and public conferences. She has also co-authored the freely accessible book Nobel Dreams of India which explains scientific concepts in an accessible way by connecting science to societal applications.

Most of her work is voluntary and stems from her drive to give back to society.

“I try to use every opportunity to interact with students or with the public at museums or whenever I have an opportunity during my professional travels,” Sharma said.

Jain, now a professor at the Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, is a scientist by training. She was pursuing a PhD from IISc when she realised that she did not want a career in research, but she didn’t want to leave the subject altogether.

“So I thought I will get into science communication. But even now I am more comfortable with my senses than my words —that’s how the idea of science and drawing came to be,” she said.

It started off as a personal project. She was drawing every day and posting it online.

Jain’s PhD guide appreciated her work and asked her to showcase it at a science festival in IISc. “People actually bought those drawings — that is when I realised that this can be a career choice,” Jain said.

These days, Jain is trying to push herself out of her comfort zone and sketch concepts from sciences that she is unfamiliar with. She is now trying to illustrate how scientists work —what they do in labs, how new ideas are created, and how they choose research topics.

“I am really interested in untangling the process of science for my audience,” Jain said. But the passion for science communication is not limited to just those who are scientists by profession.

GS, who started his Youtube channel in 2016, was driven to make science videos because he could not find the kind of ‘geeky’ or ‘nerdy’ content that he was looking for.

From videos about the tech behind ISRO rockets and India’s supercomputers to simpler questions like why the satellites do not fall back on Earth, his content focuses on explainer-type videos.

“Educational videos in India are usually for school and college students. Back when I started, there was no geek or nerd space on YouTube,” GS told ThePrint.

To fill that space, and to learn something new in the process, GS talks to his friends who are experts in various fields of science —and some even at ISRO —to demystify tech science. “There is no schedule or algorithm that I am trying to follow. Some months I could have just one video, some months I might make six,” he said. His most popular videos are explainers about ISRO’s missions.

With almost 4 lakh subscribers, he earns some money from his YouTube channel, but it’s not enough for the channel to run itself. “If I let money make the decisions, it would affect the channel’s content,” he said.

GS is not the only ‘scientist’ on YouTube. Pranav Radhakrishan runs a popular channel called Science is Dope. He realised that to make the channel ‘ more successful, he needs to create ‘myth-busting’ videos — which are far more popular than his science explainers.

Radhakrishnan was an electronic engineer before he joined an ed-tech company where he worked on creating science content.

“I noticed that this is something that the audience wanted, but there was no creator addressing it. I saw a gap in the market and thought why don’t I do something that I wanted someone else to do,” Radhakrishnan told ThePrint.

His most popular videos are under the tag ‘pseudoscience police’, where he’s taken on Sadhguru, Zakir Naik, Abhi and Niyu and more.

He has carved out a niche that makes him enough money to have left his full-time job.

But not everyone is happy with his work.

“Most of the backlash that I face is in the form of YouTube comments — those I can easily ignore,” he said. However, from time to time disgruntled viewers hit back by vindictively reporting his work for copyright violations. Now, Radhakrishnan puts disclaimers in his videos explaining why his work is not violating copyright law.

Radhakrishnan wouldn’t advise anyone to make a career out of science communication, not because of the harassment but because the viewership for pure science videos still has a long way to go.

Nandita Jayaraj, a former science journalist, knows this all too well. In 2016, she started The Life of Science, a pet project that documented the stories of women in science. The project eventually turned into a book Lab Hopping published this year.

Jayaraj said that while their cause was well-intentioned, they failed to focus on how to make their venture sustainable.

“While we were paying contributors, the challenge was that we often could not draw our own salaries,” she told ThePrint. “That is the model that we could not really crack.”

The team was able to receive grants and raise crowdfunding to run for a few years, but the website has been dormant since last year.

In Jayaraj’s experience, science communication is not the most lucrative career for those with a science degree.

Jayaraj now works as a consulting science communicator with Azim Premji University, Bengaluru She promotes the research work undertaken by the University.

Even for Sudhira, science communication is far from a profitable venture. Gubbi Lab’s research and consultancy ventures help the team fund their science communication efforts.

Also Read: India’s new tourism boom is in the sky. Uttarakhand to Andamans, stargazing on the rise

Can government intervention help?

For over 34 years, Vigyan Prasar, an autonomous institution of the Department of Science and Technology, was tasked with popularising science. In April, the department announced that it would shut down the institution by the end of July — without any explanation as to why.

In May, Dinesh Sharma, founding managing editor of India Science Wire, wrote that the institution’s demise can be attributed to its shift from its original mandate of promoting scientific temper to merely becoming a “government propaganda” platform.

“For instance, the agency started ‘DD Science’ in collaboration with Doordarshan as a one-hour daily programme for science, but it started rehashing documentaries telecast earlier,” he said.

He added that the lines between Vigyan Prasar and the RSS-backed Vigyan Bharati (VIBHA) became blurred — with officials holding senior positions at both the institutes and the two agencies conducting joint events.

Jayaraj feels that relying on the government for funds for science communication may also not be sustainable, especially now that they’ve shut down Vigyan Prasar.

The science ministry’s Department of Science and Technology also runs a programme called AWSAR – that organises a competition for PhD scholars to write their research as a popular article, said Sudhira.

But he added that outside of the competition, there is little incentive for the scholars to continue it.

Also Read: Astro labs are the new wave in UP village schools. Delhi man revolutionising physics

Can sci-comm be profitable?

Sudhira said he has experimented with different ways of bringing in revenue, including a model where leading media houses can buy science stories from their labs.

“But the media is not willing to pay for it,” he said.

It’s not all bad though, there are some who have cracked the code and turned science communication into a profitable venture.

Bhavani Giddu, founder and CEO of Footprint Global, has been focussing on promoting organisations working in the development and public healthcare sector since 2010.

Giddu would often have to work with clients whose works were published in research journals like The Lancet, and her team would have to simplify it for popular media.

“At the time, I really did not have a clue that there was something called science writing, or science communications,” she said. But her work had made an impact, she was invited by IIT Madras in 2012 to do a series of workshops on how to take the research and innovation they are doing on campus to the media.

There was a huge gap between what the media knows about science and what scientists on campus were doing, Giddu said, adding that researchers are not able to explain their work in layperson terms to the media.

Giddu trains young professionals on the nuances of science communication and has been successfully increasing science reportage in mainstream media. Among her client list are several IITs and IISERs. At present, she is exclusively working with public health and scientific research institutions.

But funding is not the only challenge facing science communicators. There is also resistance from within the scientific community, many scientists are not that interested in being featured in popular media or engaging with laypeople outside their community.

“Their first concern is that it gets trivialised in the media to such an extent that they get mocked by their peers. They also do not want their work to be misrepresented,” Giddu said.

She gives an example of how research papers that elaborate on possible cancer therapies get reported as “cancer cures”.

“That is not only incorrect and far-fetched, but it also becomes very embarrassing for a scientist to explain such reporting to their peers,” she said.

Sudhira added that the professional culture is such that scientists move on from their work as soon as they publish their papers. “ Their next job is just to get another grant,” he said.

Communicators believe that the benefits of science outreach go far beyond the altruistic, feel-good factor of giving back to society, its beneficial to the researchers as well.

“A lot of researchers have not yet understood how talking about their research to the media benefits them. It creates visibility for their research and collaboration opportunities with industries, or other academics,” Giddu said.

It also helps them, and India, get noticed in the global scientific community.

“When scientists communicate their work to a wider audience, they can increase their visibility and establish themselves as experts in their field, which can lead to new opportunities for collaboration and funding,” added Sharma.

Even those who fund these projects tend to view topics that have been more widely written about in a more positive light, she said.

Sudhira added that science outreach can help scientists get more clarity on their own research topics.

“When you try to communicate your work outside the research community, it improves your clarity of the subject. Outreach activities raise fantastic questions,” he said.

Jayaraj went one step further and said that scientists should set aside a small portion of the funds they receive for their research projects to communicate the findings of the project.

“The increase in the number of science communicators since I first started shows that there is a definite increase in readers’ interest,” she added.

But Jain noted that even though the interest in science communication has gone up, its scope is fairly limited.

“In my experience of working with scientists, the intent of science communication is often just content creation to promote their work,” she said.

They do not understand the needs of the audience and use complicated words without even trying to explain what it means.

She added that scientists tend to focus on finer details that matter to them but not the audience. “Once scientists really understand the people that they are trying to reach, the equation will change,” Jain said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)