New Delhi: In 1999, a paan-chewing Indian Apple Singh went to watch the ICC World Cup in England. The TV promo was a typical, if not condescending, portrayal of an Indian cricket fan played by actor Sanjay Mishra – a dhoti-clad man who speaks broken English. “I have two passes for the World Cup, VIP Stands, would you like to join me?” the legendary Geoffrey Boycott asks Singh, who can’t recognise the English cricketer, more famous in India for his commentary in Yorkshire accent.

Today, a similar portrayal of an Indian fan won’t make it to screen. It is Apple Singhs who own cricket globally, powered along by mass-marketing brands that target the demography of such fans and their ever-deepening pockets. Apple Singh today would offer Boycott a spare VIP ticket who, in turn, would thank him with Kamala Pasand elaichi (obviously a surrogate for paan masala), which has roped in legends Gavaskar and Sehwag and Chris Gayle for its promotion.

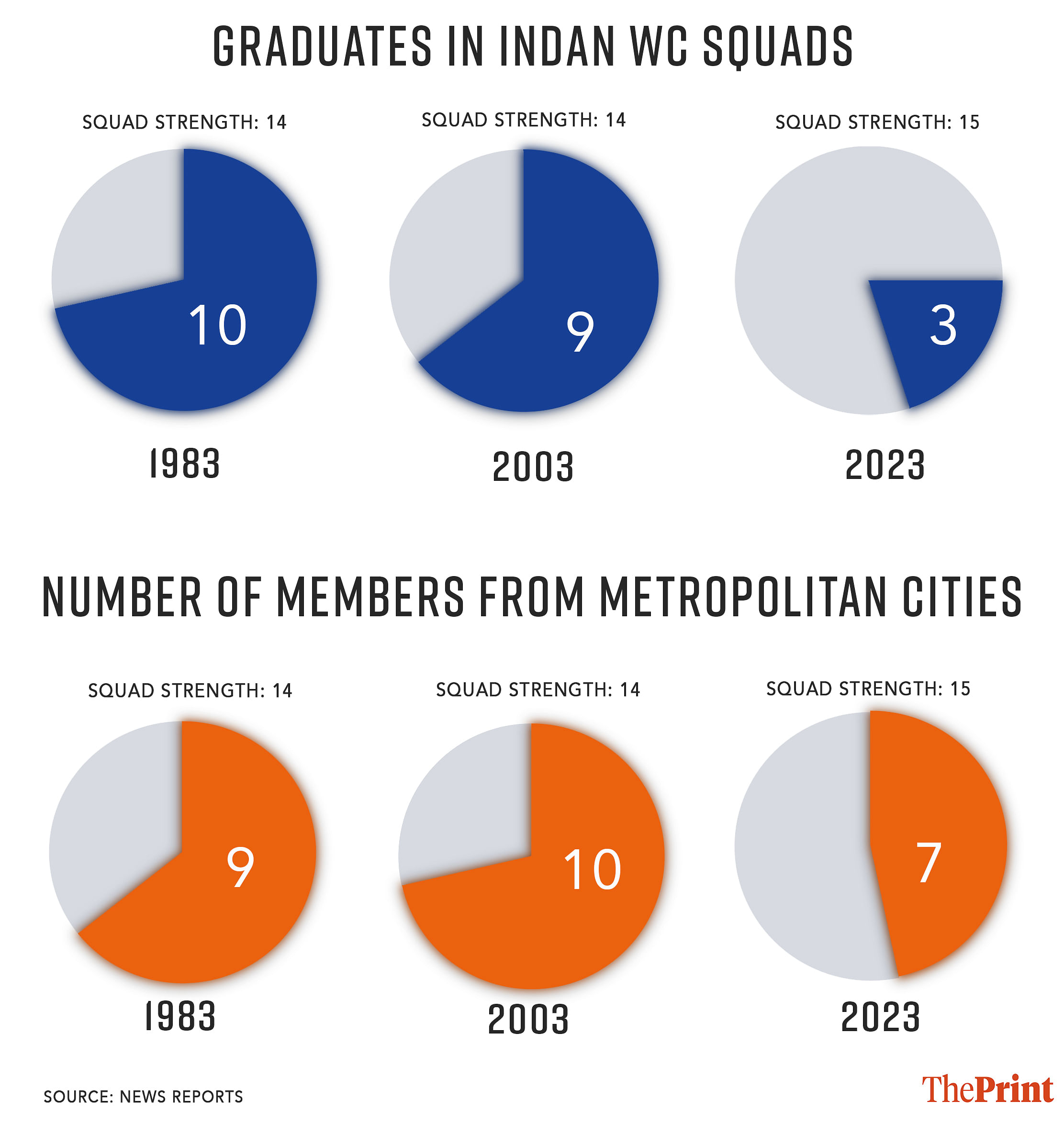

India has taken the gentleman’s game and made it its own. The team of today represents Indians like never before. Out of the fifteen current World Cup squad players, only three are college graduates. This shows the early start in the career as well as financial opportunities provided by cricket. The Indian working class has now moved on from its strict doctor-engineer dream.

Cricket is being decolonised and it’s small-town India, which buys pan masalas and affordable deodorants, smaller cars and electric scooters, that’s sponsoring the game big time. It’s a phenomenon that’s also visible every time Team India hits the ground. The epicenter of aggression is not limited to Virat Kohli’s west Delhi and its Punjabi refugee fighting spirit. Mohammed Siraj and Jasprit Bumrah, commoners from Hyderabad and Ahmedabad, respectively, now flex small town muscle in cricket. Their celebration echoes back in their hometowns. The game is reaching new, much larger audiences and brands have figured it. India’s new cricketing power on the field, and financially, is built by working class, smaller town India.

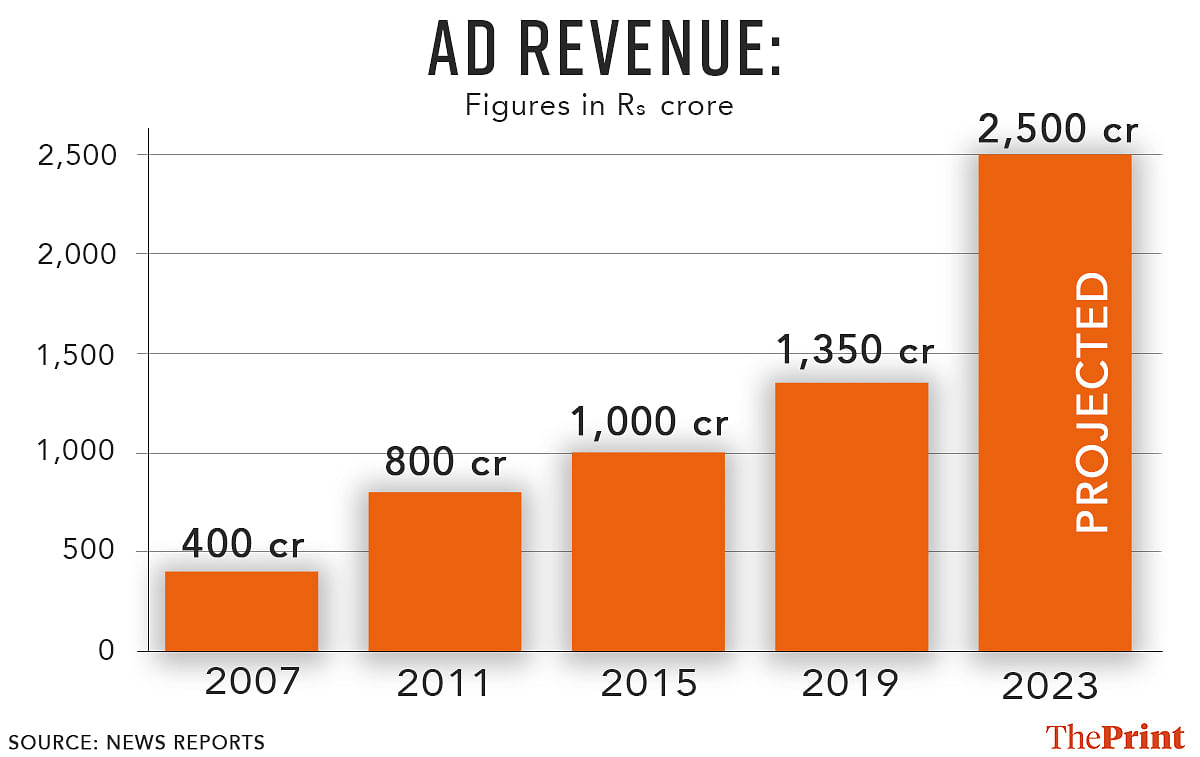

The amount of money pumped in by Indian brands gives the BCCI immense power in international cricket. It’s atmanirbhar now. “BCCI gets its money from selling broadcasting rights, and that puts it in a better negotiating position if the broadcasters are vying for the rights because of high ad revenue,” Anindya Dutta, author and cricket analyst says, adding that “at the end of the day, it is through purchasing the products advertised during the game that the people of India exert their influence on the game.

Also read: Haryana girls stood up against ‘predator’ principal. But parents, teachers pulling them back

Brands and their new heros

In the movie 83, Pankaj Tripathi, who played cricket administrator PR Man Singh, is a nifty manager of the Indian cricket team, who’s reminded repeatedly by his cricket board to make note of any expense incurred – no receipts should be missed. When the team is waiting to board the flight to England, he’s taunted about the additional baggage cost he’ll incur to carry extra pickles for the team.

Team India, the underdogs didn’t even have a sponsor. Sponsors for the World Cup was Prudential Life Insurance, an US-based life insurance multinational that today functions in partnership with ICICI Bank in India.

That changed after 1983. Kapil Dev and Sunil Gavaskar’s faces splashed across advertisements. Kapil Dev’s ‘Palmolive da jawab nahi’ for Palmolive shaving cream ads and ‘Boost is the secret of my energy’ for the malt drink were early signs of advertisers taping into the middle-class potential. Today, that class is too big to ignore and brands know it well.

The power structures of world cricket were first challenged in 1987 Reliance World Cup, which saw Dirubhai Ambani pump in Rs 9 crore. And it was legacy brands selling biscuits and bicycles that came in, hoping to ride on the success of India’s previous World Cup outing — Hero Cycles and Britannia.

Star Sports had bought digital and TV broadcasting rights for all International Cricket Council matches from 2015-2023 for $2 billion.

More than 35 years later, young brands wrapping humbler, working class products are taking the tournament forward. While there are no designated title sponsors this year, the World Cup’s official partners include homegrown brands such as Bira, Polycab, Byju’s. Out of the 18 main sponsors for the 2023 edition, nine are Indian.

A cursory look at the profile of brands advertising during the ongoing World Cup shows who is watching and sponsoring the game in India. From entry-level whisky brand Royal Stag that pushes the consumer to ‘make it large’ in life in its surrogate ad to mid-range wine Jacob’s Creek and Bira, the Indian brand of affordable beer, popular among the youth, underlines Indian cricket’s DNA is changing fast. Byju’s financial woes have not deterred the brand from investing in the World Cup fever to reach a large audience. A business-to-business brand, Polycab that sells electric wires is an official partner, with Chennai-based MRF Tyres the global partner.

It’s not just premium whiskey or premium cars or sportswear that is shining bright in between overs any longer.

Nitin Krishna, who is a social media manager for various sporting teams in football and chess, says the elite or Tier-1 city audiences have drifted from cricket. “You’ll see Rolex advertising during Tennis. The exclusivity of Tennis is something a brand of that stature wants to connect with. Cricket does not get that kind of audience in India. The kind of money the sport demands would not make sense for brands to advertise here,” he says. “Tier-1 audience in India is choosing to watch sports like Formula-1 or even basketball, football or other league sports. The sports that seem ‘cool’ for them,” he says.

That brands are trying to seduce small town India is evident in their storylines. Swanky advertisements for rural India and kifayati India have taken over. Fogg, the deodorant brand that planked its success on offering deodorant instead of ‘gas’ like a lot of foreign brands, continues to run its long running campaign in the World Cup. ‘Fogg chal raha hai’ is perhaps the catchiest tagline in the internet generation, recalled by people while watching a man and a woman braving a storm, in which only romance and the scent of Fogg survive.

At the same time, Mahindra is advertising OJA Tractors, probably the best indication that the cricket’s appeal has spread way beyond urban areas as the target market in this case are farmers. It sexes up the tractor, which is sold in visuals and storyline comparable to a SUV car, calling on India’s farmers to buy the new cool machine, not because it’s cheap but because it’s practical. It’s not just Apple selling its lakhtakiya iPhone during matches. Brands like Itel, an affordable smartphone maker, can be seen telling the story of a small town school boy who wants to buy a World Cup ticket for his father but is unable to do so. So instead, he buys an Itel smartphone for his father. Even Hardik Pandya is competing with ‘Panthers’ in a Nikeesque ad for Jindal TMT sariya (iron rods used in building construction).

“If you look at the biggest viewership numbers, they’re not coming from the metros. Rajkot, Indore, Vijayawada are some of the examples of Tier-2 cities which are bringing a chunk of viewership of live cricket,” says Arvind Sahay, director of Management Development Institute in Gurugram.

If you look at the biggest viewership numbers, they’re not coming from the metros. Rajkot, Indore, Vijayawada are some of the examples of Tier-2 cities which are bringing a chunk of viewership of live cricket

— Arvind Sahay, director, MDI, Gurugram

“There’s a certain prestige involved in advertising during cricket,” says Vikas Gupta, former CEO of Coca Cola India, explaining why a lot of brands with niche target audiences like TMT sariya, tractors, cement, deodorants advertise during cricket. “And with the high advertising rates, it makes sense for brands with a larger volume to buy ad slots. Cricket has the widest demographic in India,” he adds.

According to a press release by Hotstar India, it had a peak concurrent viewership of 4.3 crore during the India-New Zealand match, which is bound to go much higher for the knockouts. Such viewership on a digital platform makes it appealing for advertisers to scurry for slots even at their elevated prices.

Brands are selling up to Rs 30 lakh for a 10-second slot for advertising during the World Cup. According to Statista, the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of advertising during cricket is at a staggering 40 per cent rate.

“Super Bowl viewership in America peaks at 140 million. Indian World Cup matches are inviting 4 crore viewers just in India (in league stages). The viewership has also changed. Villagers are watching cricket, eco systems are being built to cater to this audience. Aspirational products for people earning Rs 30-40,000 a month are also sold, but it’s not like brands for the urban elite will completely vanish. There’s a compendium of brands advertising during cricket,” says Sahay.

Indian brands also sponsor other international teams. Amul is the sleeve sponsor for the Sri Lankan and Afghanistan cricket teams.

Also read: Wild card to wildlife, Elvish Yadav has ‘systumm’ wrapped around his finger

Claiming cricket through language

The access to cricket has increased owing to the diversity of language in the commentary offered. Indians understand and talk about the game in their own tongue. No English commentary can parallel the humour of a Hindi commentator describing a massive six, saying, “kya ye gaind Dadar jaa rahi hai”? The match was being played at a Mumbai stadium.

Hindi commentary in cricket started in the 1950s, which was the first leap towards the game reaching a wider audience. As television started competing with radio as the most preferred medium to watch the game, the aristocracy of English was restored in the throw of the voices of experts like Harsha Bhogle.

The 90s were dominated by English commentary; a shift was seen in 2012 when Star Sports broadcast the India-Australia match in Hindi. It was then the power of accessible language was realised in the boardrooms of cricket broadcasters. 71 per cent of all viewership of the India-Australia series came from their Hindi language commentary. That would see a stark change in policy of the broadcasters. In 2014, just a couple of years before the Jio revolution, Star Sports launched India’s first 24×7 Hindi commentary channel. Star Sports is broadcasting Hindi cricket commentary internationally now.

This year’s Indian Premier League was broadcast in various regional languages including Oriya, Gujarati, Bhojpuri.

The current World Cup is being broadcast in nine different languages including Hindi, Kannada, English, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi.

According to Statista, during IPL 2022, 93 per cent of all viewers consumed cricket in the Tamil language in the state, while 75 per cent people watched cricket in Telugu in Andhra Pradesh. This goes to show the preference for watching the sport in one’s own language.

Aman Misra, a sport sociology PhD scholar at University of Tennessee, Knoxville says the high numbers can also be seen in context of growing sentiment against the monopoly of Hindi, especially in the Southern states. “In today’s political climate of language nationalism offering commentary in various languages is of extreme importance,” he says. Misra added that this can be seen in conjunction with commerce. “All brands nowadays launch their campaigns in various languages, not just Hindi and English. So it is beneficial for brands as well to localise and target their consumers better by broadcasting on channels which support their language.”

All brands nowadays launch their campaigns in various languages, not just Hindi and English. So it is beneficial for brands as well to localise and target their consumers better by broadcasting on channels which support their language

–Aman Misra, sport sociology PhD scholar at University of Tennessee

Misra says the demand for vernacular languages can also be seen in the 2019 scandal, when Sanjay Manjrekar called Ravindra Jadeja a ‘bits and pieces’ cricketer. Manjrekar’s commentary was picked on for its elitist nature. It was then that a viewer also sent a postcard to the ICC, demanding better commentators. Tamil commentator, R Balaji, had in fact thanked Manjrekar for his comment since that ‘encouraged viewers to switch to regional cricket’, and said that he owes all his wealth to Manjrekar, as his comments encouraged people to switch to Tamil.

The BCCI had made it mandatory for Disney Star and Viacom 18 to broadcast cricket in at least four languages.

Misra added that regional commentary also makes the game more accessible for aspiring young cricketers. “Aspiring cricketers who must be learning the sport in their own languages, could suffer from a lost in translation if all matches were available to watch only in English. The understanding of the game improves significantly if they watch the sport in their mother tongue, and definitely makes the game more accessible.”

Also read: Gurugram men are quitting dating apps, alcohol, hiring lawyers. A woman on Bumble did this

Ball’s no more in royal court

Much like Polo, cricket was once a game of royalty. Mansoor Ali Pataudi, Hanumant Singh, Bhupinder Singh, Duleepsinhji, among others all came from rajwades across the country.

India’s first tour of England in 1932 was led by the Maharaja of Porbandar as protocol demanded that a royal lead the team.

“The kind of players in the game have undergone tremendous changes. Largely, players who made an impact came from a higher economic strata. From families where it was okay to not necessarily have a job. That is why places like SBI, Railways became important to increase the accessibility of the sport, so young men could pursue the career seriously,” Dutta says.

It is brand ambassadorship in those days, as is the case today, where players earned money to move up the economic ladder. “Faroukh Engineer advertised Brylcreem. Eknath Solkar advertised bicycles. Solkar was the son of a groundsman, one of the exceptions where the player didn’t come from a strong economic backing,” Dutta adds.

Solkar advertised Philips, a British bicycle brand. Engineer advertised Brylcreem, another British company. The current lot of players don’t have to rely on international conglomerates for additional streams of income.

The kind of players in the game have undergone tremendous changes. Largely, players who made an impact came from a higher economic strata. From families where it was okay to not necessarily have a job

— Anindya Dutta, author and cricket analyst

With time, the royal dominance of the sport waned but the social mix is still concerning. A 2018 paper by National law University, Bangalore notes that out of 289 players in Indian Test History only four have been Dalits.

Socio-economic and educational backgrounds notwithstanding, players from small towns are establishing their own kingdom, surrounded by brands hungry for their face. And they don’t need degrees to earn money. Cricket is taking care of that. Absence of graduates is evidence of the game’s changing demographic as also early talent discovery. By the time people are 16-18, they’re training/playing full time. Tendulkar is the biggest example. Back then, he was an exception. Today, it’s the norm.

Nine players in the 14-men squad for the 1983 World Cup were graduates. The team’s regional diversity was also limited. Five players were from Mumbai, while four were from Punjab. One player, Kirti Azad, hailed from Bihar, while three players were from Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Secunderabad.

After the decades of Bombay-Delhi monopoly was broken, especially during the Dhoni years, it was IPL that made the game more democratic and players richer. “Cricket was looked at as a distant dream at a point in time, now it is looked at as a sustainable career. Even if you don’t make it to the Indian cricket team, or even an IPL, first-class cricket will offer you enough money to lead a decent lifestyle,” says Vikas Gupta.

According to cricket analyst Charu Gupta, on an average, players are taking home Rs 50,000 per match if they make it to first-class cricket.

With IPL, one of the most profitable sporting leagues in the world, the BCCI’s selectors are not just lurking around in the metros of India or at elite gymkhanas, IPL selectors are travelling to the depths of the country, looking for talent. It is in these practice grounds that gems like Rinku Singh are found.

“One has to credit the BCCI which has built the necessary infrastructure so players can train in their small towns. Earlier, players had to travel to metros like Delhi or Mumbai if they had serious talent to be a cricket player,” Sharma had told ThePrint in an earlier conversation.

This accessibility is evident today in the diversity of the team. We only have three graduates in the 2023 World Cup squad– Shreyas Iyer, Ishan Kishan and Suryakumar Yadav.

The mix of the team is also diverse, with players hailing from six different states.

But not all credit can go to brands. “We have to clearly understand that brands are not here for any altruistic purposes, or with the intention to further the game,” says Sahay, “but it cannot be discounted that money poured in by various companies, and now increasingly Indian companies is a contributing factor about the story of cricket in India.”

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)