Gorakhpur: Up until a few years ago, desperate parents would rush to Baba Raghav Das Medical College in Gorakhpur with their unconscious encephalitis-stricken children dangling in their arms. Only a few would survive. Year after year, between July and September, the tragedy would repeat itself at Uttar Pradesh’s encephalitis epidemic epicentre—until now.

For the first time in four-and-a-half decades, Gorakhpur has passed its peak season without any Japanese Encephalitis (JE) cases or deaths reported. Well, almost. Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath government’s targeted strategy in his home constituency to fix its public health is now showing results.

“We attacked the cause of infection at its source. Like a good manager, the chief minister brought all the departments together and said, ‘now you all solve this’. And the officials had to obey,” said Ashutosh Kumar Dubey, chief medical officer, Gorakhpur.

It has taken six years and a coordinated public health crackdown for Gorakhpur to pull back from the worst era of encephalitis deaths. And it all came down to demonstration of priority and political will—a combination of bringing together water sanitation, health departments, improving the primary and community health centres at the rural level, bringing in specialist doctors to the Gorakhpur hospital, creating a new 500-bed dedicated facility, and battling the virus and lack of hygiene at source—the turnaround is nothing short of a public health miracle in India, not unlike the polio eradication programme.

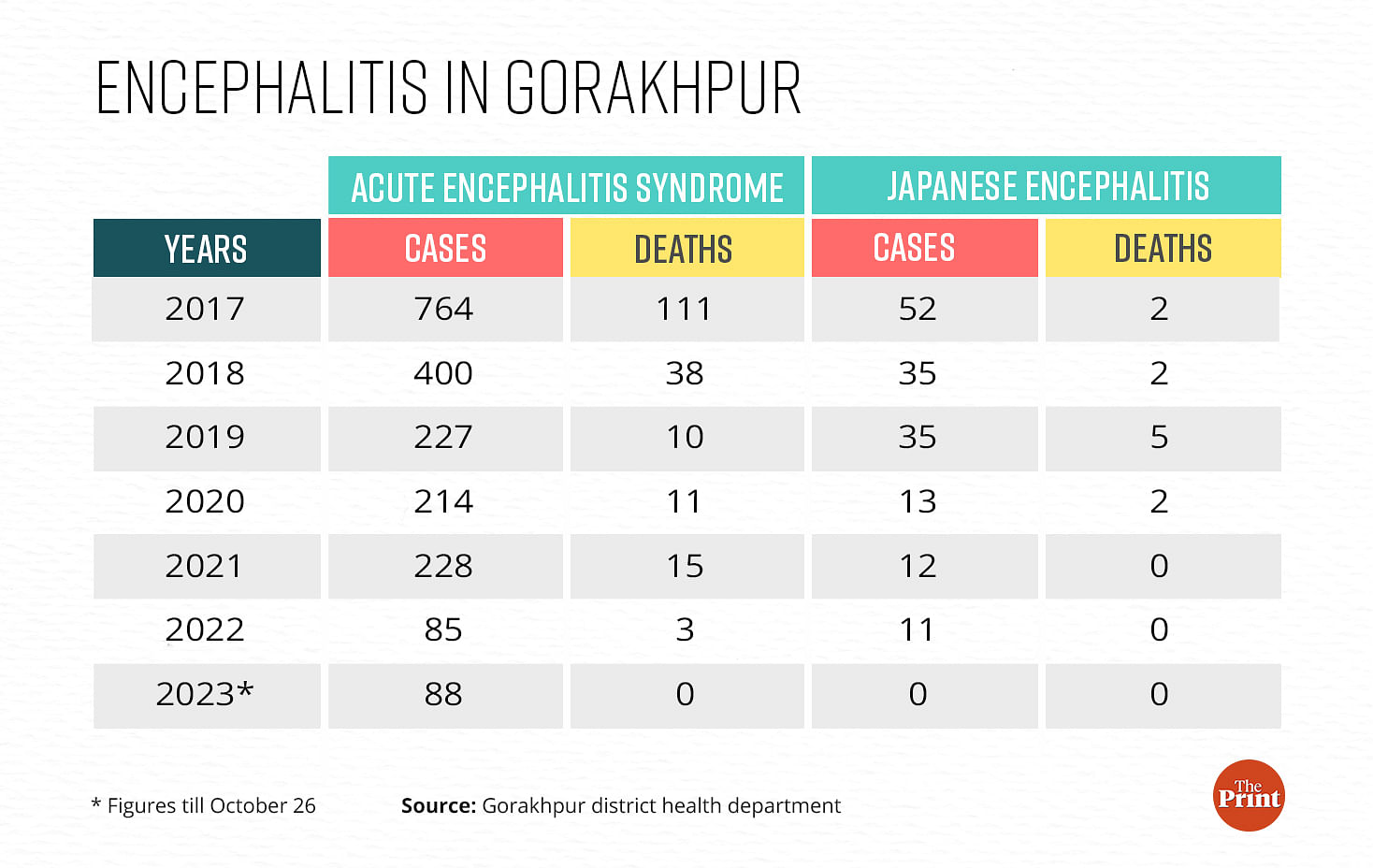

Government records show that even deaths due to acute encephalitis syndrome (AES)—where children show symptoms like high fever and seizures similar to JE but the cause of infection is unknown—is down to zero. And AES cases have dropped from 764 in 2017 to 88 this year. But that could well be because patients with high fever are no longer bunged under the AES category. Instead, they are bifurcated and, based on test results, categorised as dengue, malaria, typhoid, scrub typhus, and leptospirosis.

And patients going to the private hospitals slip through the cracks.

“Even if the private hospitals get any cases, they don’t highlight them. An AES or JE death would invite government scrutiny, which the private hospitals want to avoid,” claimed a paediatrician who runs a private practice, requesting anonymity. In their records then, AES or JE deaths are mostly labelled as ‘acute febrile illness due to unknown causes’.

BRD hospital recorded 11 encephalitis deaths this year, which additional chief medical officer AK Chaudhary argued were of patients from other Uttar Pradesh districts as well as Bihar—not from Gorakhpur. The two deaths that the hospital recorded as from Gorakhpur will be “audited” to ascertain if the patients indeed belonged to Gorakhpur, the nodal officer for AES and JE cases, Angad Singh, said.

But the transformation is unmistakable.

Before we had a PICU, we only had an encephalitis treatment centre, which was handled by a staff nurse. Now we have all the facilities that a tertiary level hospital has

—paediatrician Avinash Singh.

On 3 October, Adityanath said that JE and AES will soon be eradicated from the state. “The state government has been conducting special campaigns to control communicable diseases like dengue, malaria, encephalitis, kala-azar, and chikungunya since 2017. These campaigns have yielded good results over the past six years,” he said.

Scientists and the doctors ThePrint spoke to want to tread carefully.

“The work in Gorakhpur to bring down encephalitis has come a long way. But it will take some more time to eradicate encephalitis,” said Ashok Pandey, scientist at the Regional Medical Research Centre (RMRC), Gorakhpur.

Also read: Encephalitis cases decline steeply, yet Gorakhpur medical system feels the strain

The big change

A wide, clean staircase with potted plants and sign boards leads to a three-bed paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at Bhathat community health centre (CHC), about 14 km from Gorakhpur city. Its walls are painted with colourful cartoon characters, while three ventilators, several monitors, an incubator, a heater and colour-coded dustbins are neatly placed in the room.

Until June, before the PICU started functioning, this secondary-level hospital used to refer patients with high fever and convulsions to BRD hospital. But with the refurbished room, the CHC received a paediatrician, four MBBS doctors, four staff nurses, a lab technician, and a ventilator operator. When the cases peaked, all three beds were occupied.

“Before we had a PICU, we only had an encephalitis treatment centre, which was handled by a staff nurse. Now we have all the facilities that a tertiary level hospital has,” said paediatrician Avinash Singh.

About 16 km from Bhathat, in Chargawan primary health centre (PHC), a room with two beds is the designated encephalitis treatment centre (ETC), and allocated exclusively for patients with high fever. Its cupboard is stocked with medicine and a staff nurse is always on duty.

“A few years ago, the situation was dreadful,” says Dhanjay Kushwaha, doctor-in-charge of Chargawan CHC. People would bring their children in a critical condition to the PHC that did not have staff or medicine. “Now the children are kept under observation for two to three hours. They are referred to BRD hospital only if their condition deteriorates,” said Kushwaha.

Activists working on encephalitis in Gorakhpur say that until a few years ago, there were only buildings in the name of PHC and CHC, with no doctors, medicine, or equipment.

“The ETC was just a partition of a room with a green curtain and two rickety beds. The hospitals did not even have oxygen at times. People did not trust the government hospitals,” says Rajesh Mani, a social activist.

But 2017 was a turning point. At least 60 children died over two days in BRD hospital when the oxygen supply was stopped allegedly due to non-payment of dues. The incident sparked nationwide outrage, made international headlines, and led to the arrest of several staff—from junior clerks to doctors, including Dr Kafeel Khan from the paediatric ward who had helped arrange several oxygen cylinders on his own. It was a wake-up call for the Adityanath government, showing how its public health infrastructure lay on life support.

A few years ago, the situation was dreadful. Now the children are kept under observation for two to three hours and referred to BRD hospital only if their condition deteriorates

—Dhanjay Kushwaha, doctor-in-charge of Chargawan community health centre.

Also read: 2 yrs on, UP probe clears Gorakhpur doctor Kafeel Khan of medical negligence, other charges

BRD’s transformation

By November end, the paediatric ward will shift to the 500-bed multi-storey building with spacious, tiled corridors, ventilators and waiting area. It’s a 180-degree turnaround from the chaos and mayhem that marked the years since 1978, when the first JE case was reported at the BRD hospital.

RN Singh, a young doctor then, was on duty when a child with high grade fever, convulsions and loss of memory was brought in. The paediatric ward only had 10 beds at the time.

“No one could understand this case. I was very junior,” said Singh, who now runs a private practice in the city.

The case opened the floodgates. Soon, beginning July every year, sick children began getting admitted. Chaos and mayhem reigned until September. Eastern UP became endemic to JE and BRD hospital was the lone tertiary hospital, including for patients from Bihar and Nepal. By 2017, the paediatric ward had 217 beds. But that wasn’t enough.

“There used to be so many sick children and their parents everywhere in the hospital, holding saline bottles in their hands. We used to climb the stairs carefully to avoid stepping on people,” said scientist Pandey. He and his team would collect samples from infected children for testing. Each bed had up to four children, and the scientists would go to every one of them to draw fluid from their spinal cords.

“By the time we would move to the second section of the room, three children from the first section would have died,” he recalled.

2005 brought JE to the attention of politicians. But for several years after that, leaders visited the hospital only for pomp and show. Nothing changed on the ground

—Rajesh Mani, activist who filed a PIL in the Allahabad High Court

The patient load was such that the general paediatric wards would turn into emergency units. “It was very painful to watch young children die. There were very few doctors and nurses and we had limited resources at our disposal,” said Meena, a senior nurse who has been working at BRD hospital since 2006.

The calamity of 2017 paved the way for improvement.

Stinky corridors with dirty floors are now scrubbed with disinfectants. Walls earlier covered with spit are now plastered with clean white tiles. The number of beds has gone up to 428. From 20,000 litres of backup oxygen, the hospital now stocks 70,000 litres. It has also seen a spike in ventilators, infusion pumps, warmers, and monitors. Moreover, to fill up the requirements of paediatricians at PHCs and CHCs, BRD medical college has started training 20 MBBS graduates in a specialised paediatric course, skilling doctors to handle encephalitis cases.

“Once we shift to the new building, there will be one patient on one bed and no cross-infection,” said Ganesh Kumar, principal and dean, BRD medical college.

Also read: Too rich for govt schemes, too poor to go private — prepaid health card targets ‘missing middle’

Targeted approach

Merely painting the buildings won’t cure the disease that was rotting Gorakhpur. The state knew it needed to get to the root cause.

In 2018, the Adityanath government launched Sanchari Rog Niyantran and Dastak campaigns with specific mandates for each department. The sanitation department had to keep toilets functional; the water department had to fix shallow hand pumps and supply piped water; the panchayati raj and rural and urban development departments had to ensure garbage disposal, weed cutting and fogging. Anganwadi centres had to provide timely food ration to children to target malnutrition. And the education department had to disseminate information.

The campaign started three times a year—before, during, and after the rains.

“The ASHAs and ANMs went door-to-door to actively look for cases of high fever. The idea was to detect fever cases as early as possible and take the children to hospitals before the fever enters the brain,” says Angad Singh, district malaria office and the nodal officer for the campaigns.

The state’s free ambulance services, 108 and 102, were roped in. And where a child with JE or AES was detected, the district team would survey the area to detect stagnant water or any other contamination.

“Within one year, AES and JE cases fell by almost 50 per cent and deaths by 63 per cent,” said Singh. In 2018, 435 AES and JE cases were detected in Gorakhpur district. These dropped to 262 in 2019. From 40 deaths in 2018, the toll came down to 15 in 2019.

Research is the backbone

When Pandey landed in Gorakhpur in 2008 to set up a virology lab, a branch of National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Pune, all he had was an abandoned building with a big hall at one corner of BRD hospital’s campus. It was a small structure almost submerged in water.

“To reach the building, I had to roll up my pants till my knees and wade through the water,” Pandey recalls.

He brought residue from brick kilns to carve out a walking path, fixed the electrical wiring and had a water tanker installed. On two tables in the hall, he set up the machines to kickstart a makeshift virology lab.

Before the lab was established in Gorakhpur, the samples were sent to NIV Pune, via Lucknow by road, for testing and the results would arrive in 40 days. By the time Pandey and his team landed in Gorakhpur, the district had already witnessed a calamity. 1,300 children had died in one of the worst JE outbreaks in 2005, as per official records. But the actual numbers were much higher, allege activists.

“The year 2005 brought JE to the attention of politicians. But for several years after that, leaders visited the hospital only for pomp and show. Nothing changed on the ground,” said Rajesh Mani, an activist who filed a PIL in the Allahabad High Court in 2009 against state inaction.

But the case fell in a limbo while images of children wrapped in shrouds, released by the press, continued to haunt the state.

“At that time, all cases were assumed to be JE. The mortality was high at 30 percent and another 30 percent who recovered had permanent disability,” said RN Singh.

With limited research, helpless doctors were shooting in the dark. JE has no cure. Pigs, which were the carriers of JE virus, were moved out of the villages. Vaccination drives launched in 2006 and then in 2010 had little impact.

Sound research-based interventions were desperately needed.

When the scientists got to work, they found out that in 2005, only 30 to 35 per cent cases were JE infected. The rest of the children were falling sick with an unknown infection, which was showing the same symptoms as JE. Children would get high fever, seizures and they would be disoriented. All non-JE cases were clubbed under the broad category of AES.

In 2007-08, a new cause of the disease was found — contaminated water. So, along with pigs, focus shifted to removing shallow hand pumps in villages. But the enterovirus infections caused by contaminated water were still a small fraction of illnesses.

In 2013, an expert from Vellore visited Gorakhpur and suspected the presence of a neglected bacterial infection—scrub typhus, says Pandey. The expert doubted cross-infection from the lice of sick children as they were put together on the same bed. Some of the children were developing puffiness and rashes, while their heart and liver would be inflamed and their organs would start to lose function within days of getting admitted.

When the NIV team tested 300 samples, 200 came positive for scrub typhus. While the symptoms in infected children clinically matched with scrub typhus, doctors at BRD were not convinced.

“The doctors’ doubts were not unfounded. Scrub typhus is treatable with antibiotics. But it was not effective on critical patients. Doctors could also not believe that a bacterial infection was causing repeated outbreaks, as it is uncommon. Bacteria are also bigger in size, making it difficult to enter the central nervous system and damaging the brain,” said Pandey.

The challenge was now to prove the presence of scrub typhus in the environment. The NIV teams went to the villages with rat cages and trapped rodents and shrews. The results were a breakthrough.

“We found scrub typhus infection in the lice found in the ears of the rodents. It was 20 times of what it should be normally,” adds Pandey.

But in the state government’s health department, the counting of scrub typhus cases started only from 2022 onwards, after 36 cases were recorded that year. This rose to 76 until October this year.

In 2016-17, NIV also published a study that showed infected children can fully recover if given early treatment with antibiotics. However, once the infection spreads to the organs, the medications become ineffective.

“There is a resurgence of scrub typhus in the entire Southeast and South Asia due to climate change in the last seven to eight years. And scrub typhus emerging in eastern UP is a part of this phenomenon,” says Pandey.

The central government’s guidelines on scrub typhus treatment came in 2017, four years after it was first discovered. It advised doctors to give antibiotics to fever patients in the endemic regions.

“A series of measures then brought the cases of encephalitis down. The antibiotics helped in scrub typhus cases, JE vaccination brought down JE cases and early detection and treatment of fever cases resulted in very few cases turning into AES where the fever enters the brain,” explains Pandey.

Also read: Children continue to die in scores in Gorakhpur’s killer ward. No outcry?

Fall in cases, but how?

As the research evolved, the classification of children with high fever kept getting more specific. Cases are now checked for dengue, malaria, typhoid, JE, scrub typhus, and another bacterial infection, leptospirosis. The NIV, which has now been converted into ICMR’s regional centre, or RMRC, could not, however, confirm a high presence of leptospirosis infection.

Due to these new classifications, the number of AES cases has decreased. “All high-grade fever cases are now classified as acute febrile illness, not AES. If the sample is negative for all six tests and if the patient suffers from convulsions and disorientation, only then is it called AES,” explains Angad Singh.

But the decreasing numbers in the government data sheets do not match the ground realities. In BRD hospital’s paediatric intensive care unit, which continues to operate in the old building, two children still share a bed, and the ventilators and monitors beep constantly. Most of these cases are of high fever.

While the district records show only 88 cases of AES and no deaths this year, the hospital alone recorded 250 AES cases until 29 October. Out of these, 11 children aged between two and 12 died. Eight out of these deaths happened in October.

Explaining the discrepancy in numbers, additional chief medical officer, AK Chaudhary, clarified that the high cases and deaths are not from Gorakhpur district. “Since BRD hospital caters to patients from the entire region, the cases and deaths must be from Bihar or from other districts of UP,” he said.

The hospital records, however, show that two deaths are from Gorakhpur, and these do not find a mention in district records. Singh said that the two cases will be audited to ascertain if the patients belonged to Gorakhpur.

All’s not well

In villages about 45 km from Gorakhpur city, ThePrint found that the meticulously drafted micro-plans for prevention are barely functional.

Last year, Karauta village of Brahmpur block, on the border of Deoria district, made it to a list of 20 high-risk villages for AES and JE, according to the district administration. This happened when five-year-old Ankita died of AES.

She had fever, was vomiting for more than three days, and had taken medicine from a quack. When her eyes rolled up and her body stiffened into a convulsion, her parents rushed her to two private clinics. By the time she reached BRD hospital, it was too late. She died after being put on ventilator support for four days.

There is a deficit of trust in the government. Sati Prabha, Ankita’s mother, says that in six years of the Sanchari and Dastak campaigns, no ASHA or ANM ever knocked on their door to inform them about what to do when fever strikes.

A few houses away, seven-year-old Piyush has also been lethargic because of a fever for the past few days. His father, Surinder Kumar, took him to a private clinic in Deoria where he tested negative for typhoid. But despite the medicine, his fever is not reducing. He too hasn’t heard from the ASHAs or the ANM about the brain fever and what is needed to be done to prevent or treat it.

In the area surrounding the village, animal excreta is drying outside houses. Drains are clogged with decaying garbage and mosquitoes fly over stagnant water in the fields. Shrubs and bushes, which are the breeding grounds for infection-loaded rats and shrews, are growing wild. The fever cases are missing in the records of two ASHAs in the village. And Gorakhpur’s BRD hospital is still the last port of call for high-grade fevers.

“There were no means to go to Gorakhpur earlier. When people fell sick, we used to carry them on a charpoy and walk for four to five hours to reach the place where we would find a jeep. Our shoulders used to bruise. Now almost every house has a two-wheeler,” says Matelhu Prasad, a resident of Karauta village.

Yet, they avoid a ride to the nearest government hospital when their children get fever. Their trust in government hospitals will take time to be restored, Prasad adds.

“We don’t know if the government hospitals give effective medicine or not. We never go there,” says Surinder.

(Edited by Prashant)