New Delhi: Rupali Tripathi’s kittens were doomed. The person who was supposed to give them a loving home brutally beat them instead. On top of that, the Delhi government veterinary hospital was garbage-strewn, thinly staffed, and short on basics like cotton and bandages. Tripathi’s ordeal ended in five dead kittens and a Rs 1.5 lakh bill.

After rescuing the kittens from their adopter, Tripathi rushed to the Masoodpur government veterinary hospital but quickly realised it was pointless to seek treatment there. An injured dog lay on a broken stretcher, the floor was stained with blood, and staff worked without gloves.

“The government hospital is pathetic. No one should go there with their pets. Even basic treatment can’t be provided there,” she said. Despite the high cost, Tripathi sought help at a private clinic, but it was too late.

But Masoodpur is not an isolated case among the Delhi government’s 77 veterinary hospitals and dispensaries.

ThePrint visited several of these facilities in late October and early November and found a disturbing pattern —rundown buildings, staff shortages, lack of medicines, water and electricity issues, malfunctioning equipment, and unsanitary conditions. Some hospitals were just abandoned.

Economically disadvantaged residents and their animals bear the brunt as more affluent Delhiites opt for private clinics.

Private places charge around Rs 1,000 for just one night. How many people have that kind of money to spend on an animal?

-Asher Jesudoss, animal welfare activist

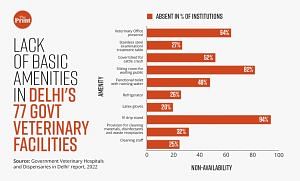

Last year, a group of animal activists compiled a hard-hitting report after visiting Delhi’s 48 animal hospitals and 29 dispensaries. Words like “abysmal,” “dilapidated,” and “unhygienic” appeared frequently in the report. One dispensary doubled as a badminton court, and part of another hospital was co-opted for use as an MLA’s office.

The activists flagged the “complete breakdown of government veterinary services” to Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and Development Minister Gopal Rai, responsible for the Animal Husbandry Unit (AHU) overseeing these facilities. When they did not get the response they wanted, they petitioned the Delhi High Court, which is currently hearing the case.

Their PIL demands action from the Delhi government, the Animal Welfare Board of India, and the Veterinary Council of India to rectify the lack of facilities, hygiene, and staff in the city’s veterinary hospitals.

“The veterinary practices being carried out in the premises do not conform to the minimum standards of any medical procedure or scientific process,” says the report by activists Asher Jesudoss, Akshita Kukreja, Aarti Bhavana, and Deepika Kini. It warns that this situation is a public health risk, as it increases the likelihood of diseases spreading from animals to humans.

The report also highlights that government facilities are meant to provide free services to the public, but in failing to do so, they are defeating their purpose and are a “waste and misuse of taxpayer money”.

While the state government has denied the allegations in an affidavit, a senior official from the AHU acknowledged the worsening state of veterinary facilities. “It was nicer when I first moved here more than two decades ago, but the facilities and infrastructure are deteriorating daily,” he said.

The report outlines a grim scenario— four hospitals and six dispensaries are defunct, and out of the 67 that are operational, none offer inpatient facilities.

Also Read: Pedigree dogs are India’s new therapists. ‘Rent-a-dog’ latest business on the block

Badminton, ludo, but few clinical facilities

Animal rights activist Asher R. Jesudoss is always on call, juggling rescues and dispensing pet advice. His phone starts ringing early and incessantly. But Jesudoss’ one advice for anyone who calls with an ailing dog or cat—take them to a private clinic if possible during an emergency due to the lack of facilities in government vet hospitals.

Jesudoss pointed out, however, that even “basic” care in a private clinic is a luxury for most.

“Private places charge around Rs 1,000 for just one night. How many people have that kind of money to spend on an animal?” he asked.

Jesudoss was one of the activists who conducted visited the Delhi government’s veterinary facilities between December 2021 and February 2022.

“Children were playing badminton in one hospital’s premises while people were parking vehicles in others. Officers were seen playing ludo. And some hospitals were abandoned,” he said.

Their report outlines a grim scenario— four hospitals and six dispensaries are defunct, and out of the 67 that are operational, none offer inpatient facilities. Outpatient department (OPD) services are only available for four hours in most hospitals, and a veterinary officer isn’t always present even then.

There is no dignity in death either. A veterinary officer told ThePrint that there are no separate post-mortem facilities in most hospitals and no place to bury or burn animal carcasses. Pet owners simply abandon the bodies or bury them wherever they can find a spot.

While Jesudoss is no longer part of the Delhi High Court petition, he said he is supporting the petitioners.

In June, the director of the Animal Husbandry Unit filed an affidavit in response to the petition, denying most of the allegations. It claimed that government hospitals were successfully treating a large number of animals and facilities were being upgraded

According to the affidavit, the hospitals and dispensaries treated 367,170 animals last year (up to November) and more than 5 lakh animals in each of the previous three years. It also claimed that the Indian government had approved the acquisition of nine mobile veterinary clinics under the Central Sponsored Scheme for 2021-22.

The Delhi government allocated Rs 6.23 crore for hospital and dispensary repair and renovation work in 2021-22 and Rs 6.17 crore in 2022-23, according to the affidavit.

Jesudoss is sceptical. “We have not found the mobile vet clinics they are talking about in our survey,” he said. “And even if they have these mobile units, who is running them? Where are the drivers? Who are the doctors?”

Jesudoss said the petitioners will respond to the government’s affidavit in the upcoming December hearing. The team conducted follow-up surveys of vet hospitals in September and October and are compiling their findings, which they plan to present in court.

Stalled upgrades

The Delhi government greenlit a revamp of its veterinary facilities three years ago, but the outcomes have been scant.

Veterinary professionals, from doctors to support staff to livestock inspectors, are frustrated with their working conditions. They claim their complaints to higher-ups have fallen on deaf ears.

A senior AHU official said that in 2020, CM Arvind Kejriwal and development minister Gopal Rai issued directives to upgrade facilities, but progress has been slow due to Covid-19, bad weather, and “administrative issues”.

The Irrigation & Flood Control Department (I&FC) and Public Works Department (PWD) provided estimates for 40 healthcare facilities, but only 23 received budget allocations. Of these, four have been completed, six are under construction, six are in the tender process, and 40 per cent of Jharoda Dairy Hospital is complete. Work has not yet started on the remaining facilities.

“This is the work of PWD, and it has its own limitations. Sometimes the tender takes time. Many times, PWD officials do not know what the requirements of a vet hospital are. They often raise objections regarding land or structure, which causes delays,” said the official.

The PWD is submitting estimates for 11 new veterinary polyclinics, 11 district societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals (SPCAs), as well as for the renovation of existing hospitals and dispensaries, according to the official.

I don’t have much money. I get free treatment here so I am able to help many animals. We just need to make these hospitals more accessible

-Kaushal, Delhi student & animal lover

The Delhi government allocated Rs 6.23 crore for hospital and dispensary repair and renovation work in 2021-22 and Rs 6.17 crore in 2022-23, according to the affidavit.

Over the past three years, the animal husbandry department has allocated Rs 12.44 crore to the I&FC and PWD for hospital and dispensary construction and repair, the AHU official said.

“The PWD is not utilising the funds fully,” he alleged.

According to him, if the previous budget allocation has not been fully utilised, there is reduced allocation for the following year. In the last three years, he said, only 30 to 40 per cent of the budget has been used, leading to budget cuts.

ThePrint has sent inquiries to PWD officials through email and phone but is yet to receive a response.

Long recruitment & short-staffing

The Bhatti Mines vet hospital, comprising two tiny rooms, has been due for a shiny makeover, with the government allocating over Rs 49 lakh for its renovation last year. Yet, the facility has been shut for several months, leaving residents—mainly labourers and farmers—in a bind.

Treating their livestock and pets is now a major roadblock. They have to travel 6-8 km to Fatehpur Beri for veterinary care. The bigger the animal is, the greater the cost of transport.

“This hospital is lying vacant due to an acute shortage of staff and a lengthy recruitment process,” explained the veterinary officer cited earlier.

The shortage of staff is due to the chronically slow process of filling vacant posts, said the senior AHU officer.

It takes two to three years for Class 1 gazette doctors from UPSC to join as veterinary officers; there are 12 vacant positions in Delhi currently.

The official added that until 2021, there were 117 posts for livestock officers, but due to non-recruitment, these have been reduced to only 108. Of these, 56 positions are currently filled, while 52 remain vacant.

Many vets, meanwhile, struggle with jobs that don’t align with their expertise. Because of the post-Covid surge in pet acquisition, vets trained for treating large animals are also tasked with caring for smaller animals like rabbits and hamsters.

“We are doctors of big animals. How can we treat small animals? We do not have any expertise to treat such animals, but we are forced to do so. Why doesn’t the government open colleges to prepare such vet experts?” said a veterinary officer from Northwest Delhi on the condition of anonymity.

In April, Gopal Rai announced that construction is underway on Delhi’s first veterinary college, to be built on 56 acres in Satbari.

Liv-52 and paracetamol for pets

At a Northwest Delhi clinic, a doctor prescribed the Ayurvedic liver tonic Liv 52— to a dog.

“More than half of the drugs we use for animals are actually meant for humans,” he shrugged.

The vet said there were very few veterinary medicine manufacturing companies due to limited demand, resulting in a shortage of drugs tailored to animals.

The veterinarian said that there was a major need for animal-specific treatments, as well as college courses on veterinary pharmacology. But until then, practitioners must rely on jugaad.

We are doctors of big animals. How can we treat small animals? We do not have any expertise to treat such animals but we are forced to do so.

-veterinary officer from Northwest Delhi

Doctors calibrate dosages of human medicines like paracetamol to the size of the animal. This is a science in itself, as some animals can become sick if given medication that is not suitable for them. For example, veterinarians do not give paracetamol to cats because it can damage their lungs.

In response to accusations of medicine shortage, the AHU informed the Delhi High Court in their affidavit that they distributed 61 essential medicines worth Rs 58 lakh to veterinary facilities in June 2021 and launched a tender for 73 essential medications, totalling Rs 5.49 crore, on Delhi’ e-procurement website in March 2022.

However, the senior AHU officer said that the department is “not able to procure medicines as per requirement”. Only the most essential lifesaving drugs are available for animals.

He attributed this partly to “administrative” reasons.

“If a proposal for 150 medicines is sent, 50 of them are cut,” he said, pointing to the vagaries of a multi-tiered approval process for the rate list.

A veterinarian in Southeast Delhi suggested that a solution to this issue would be to establish a rate contract with the company to provide medicines at a fixed rate. This, he said, would avoid wasting time on reviewing and purchasing individual rates.

Also Read: After G20, animal rights activists demand overhaul of MCD veterinary dept — ‘act only on complaints’

Cream of the crop

The support staff at Jharoda Dairy Colony’s three-room veterinary hospital take pride in their resourcefulness — they rigged up the electric line to an old fridge years ago, and now medicines and vaccines stay fresh.

The government is constructing a new building for this hospital, and though construction is stalled, they have visions of it turning out like some of the fancy hospitals that even have an AC.

Changes have been afoot in Delhi’s veterinary care system.

In April, Gopal Rai announced that construction is underway on Delhi’s first veterinary college, to be built on 56 acres in Satbari.

Then, there are a handful of ‘model’ facilities. In 2019, the Delhi government opened a 24-hour veterinary hospital at Tis Hazari, and announced that two more government vet hospitals, in Ghazipur and Palam, would follow suit.

However, Palam’s hospital currently only operates for 12 hours due to manpower and resource shortages. Tis Hazari and Palam have air conditioning and ample space but leave much to be desired on the cleanliness front.

Another hospital that stands out is the recently renovated Pahladpur facility. It has air conditioning, marble floors, and artistic animal cartoons on the entrance walls.

Eighteen-year-old Kaushal from Usmanpur strolled out of Tis Hazari Hospital, cradling a puppy. The animal lover is a frequent visitor to government veterinary hospitals.

“Being a student, I don’t have much money. I get free treatment here, so I am able to help many animals. We just need to make these hospitals more accessible,” he says, stroking the pup.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)