Darjeeling: Sudhan Chhetri shoos four-year-old Julie away every time she comes to greet him. “It breaks my heart,” he said, watching her retreat. He’s known her since her birth, but he has no choice. In two months, Julie, an endangered red panda at a Darjeeling zoo’s conservation centre, will be rewilded. With only 10,000 red pandas in the wild—the world over—a lot is riding on her future.

In the same month that the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) suspended Delhi Zoo’s membership for six months for chaining its lone African elephant, it hailed Darjeeling’s efforts to conserve red pandas. The Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park’s red panda programme is the first Indian project to be shortlisted in October this year for the global conservation award by the WAZA.

Over the last two years, Topkeydara Conservation Centre, which is run by Darjeeling’s Padmaja Naidu Zoo, has successfully released nine red pandas into the wild. Julie will be the 10th.

The zoo hasn’t stopped there, though. It’s scripting history for the conservation of Himalayan animal species both in India and abroad. In June this year, it became the first and only centre in the country to establish a genetic biobank facility to preserve the DNA and genetic material of endangered animals like red pandas, snow leopards, and Himalayan tahrs.

Padmaja Naidu Zoo wants to change the way Indian zoos operate. The rest of the world is taking note as well.

A team of scientists and caretakers are training Julie and two other red pandas for their eventual release into the coniferous forests of the Singalila National Park. Chhetri is one of the caretakers, helping develop the pandas’ anti-human tendencies. The endearing furry mammals are pioneering soldiers, part of India’s only conservation breeding and rewilding programme for red pandas. Today, the red pandas with their russet coats, bushy tails, and fluffy white ears and cheeks have become Darjeeling’s unofficial mascot. They’re on booklets, cafe signages, and shop posters, attracting tourists from across India and the world.

But simply repopulating forests is not enough to save the species from extinction. The focus here is conservation through genetic diversity.

“We’re a small zoo in a hill town with restricted space. While we cannot expand horizontally, we plan to expand vertically – by going above and beyond in conserving our existing species and protecting their ecosystem,” said Basavaraj Holeyachi, director of the Padmaja Naidu Zoological Park.

Also read: A to Z of AQI—Why Delhi can’t breathe easy

Unofficial mascots

Along the busy mall road of Darjeeling, roadside tea sellers urge foreign tourists to go see the red panda. “Something you’ll find nowhere else in India,” said one vendor enthusiastically.

With the success of the conservation breeding programme, red pandas are now a household name in Darjeeling. They feature in every tourism booklet in the hill town. In summer, the Padmaja Naidu Zoo sees close to 18,000 visitors a day, making it one of India’s busiest zoos.

Lucia and Tomas, a couple from Sweden, didn’t need a reminder. They came to Darjeeling to see two things — the Kanchenjunga and the red pandas. Once at the zoo though, they said they barely spent any time with the other animals, choosing to focus instead on the two pandas named Shambhu and Swati in the enclosure.

“I love the pandas, I’ve seen them grow up. But when visitors come here, I tell them — after the pandas, why don’t you visit the Himalayan Tahr? It is also an endangered species, and we do conservation breeding for it too,” said one of the zoo keepers who did not want to be named.

Julie and the two other red pandas who will soon be released into the wild are far removed from the zoo. They live in the highly secure Topkeydara Conservation Centre, an hour away from Padmaja Naidu Zoo by car. But the centre, with its 10 red pandas and seven snow leopards, is closed to visitors. All the animals live in separate enclosures spread across five hectares of land. Every vehicle that enters through the hilly, tree-lined pathway is carefully sanitised to keep germs out, ensuring the enclosures for these rare species stay as safe and clean as possible. Along with 10 permanent staff members, a group of 4-5 researchers study the animals’ movements, eating habits, health and well-being.

Alone in her enclosure, with no Chhetri to feed her, Julie is learning how to forage for fruits and honey every morning. Her dense green enclosure overlooking the Kanchenjunga peak has been stocked with bamboo plants and rhododendrons. Tall karaka trees with interlocking branches resemble her habitat in the wild.

The researchers and caretakers have come up with training schedules for the red pandas.

“It involves everything from learning how to climb high trees, find food, identify predators, and stay safe, most of all,” said Prajwal, one of the researchers who manages the red panda programme. So far, nine have been successfully released.

“These are captive-bred pandas, you can’t just rewild them with no training. They need to be acclimatised,” he added.

Red pandas are solitary, reclusive, and elusive, making it difficult to get an accurate census. But there’s a quiet urgency in the conversation programme here. The pandas are in danger of becoming extinct.

The remaining 10,000 red pandas are limited to China, Bhutan, and Northeast India. Officials at the Darjeeling Zoo said there are less than 50 red pandas each at the Neora and Singalila national parks in West Bengal.

Researchers in Padmaja Naidu Zoo are targeting one of the main reasons for the declining population of red pandas – inbreeding depression.

“Red pandas are solitary animals who stay high up in the trees and have very small ranges in the wild. So if there’s a population of 30 red pandas in the Neora sanctuary, chances are they will breed only within themselves,” explained Holeyachi.

This eventual inbreeding leads to decreased genetic diversity.

“Just like in other species and humans, inbreeding is never good for the fate of the species.” Animals become weaker, increasingly lose their immunity, and have lower survival rates. Add to this the rapid destruction of their habitat and incidents of poaching and hunting for their fur; red pandas in India were inching toward extinction.

That is until the Darjeeling Zoo stepped in. Back in 1992, the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) of India came up with the names of 35 endangered species in India that needed to be bred in zoos for conservation. Padmaja Naidu, set up in 1958, was one of the first Indian zoos to step up to this role. It began as a small programme at the centre itself before shifting in 2011 to the Topkeydara Centre.

After acquiring a ‘founder species’ for red panda breeding by 1992, the zoo was ready to rewild its first batch in a decade. Two female red pandas were released into the wild in 2002.

“One of them is said to have mated in the wild too, but technology back then wasn’t developed enough to keep track of the rewilded animals,” said Holeyachi.

After a 20-year gap, they tried again, and this time, the zoo hit a hattrick. In 2022, the zoo attempted to rewild four pandas in the Singalila National Park. They went with three more in 2023 and two in 2024. Of the nine red pandas that have successfully been released into the wild, three females have mated with wild red pandas to give birth to five cubs.

Their goal is to release at least 20 red pandas into the wild in five years.

Also read: Climate action is the hot new career. Consultancy, communications, colleges are all in

The snow leopards and newt

A few minutes downhill from Julie’s enclosure, three-year-old female snow leopard Prasanna watches over her two baby cubs. Surrounded by shrubs on all three sides, her enclosure has been specifically designed to resemble the undulating terrain that is her natural habitat. When a caretaker kneels near the chain link fence to look at one of her cubs, Prasanna leaps up from her post and charges toward him, growling hard.

“She’s a new mom, so quite protective of her cubs right now,” warned Prajwal. “Her cubs, only three months old, are VIPs in our centre.”

But for now, only the red pandas are being rewilded.

The Darjeeling Zoo is the only place in Southeast Asia that has a conservation breeding programme for snow leopards, which has been underway since 1989. But plans for rewilding them remain a distant dream.

“Rewilding snow leopards would be an entirely different and extremely challenging task as compared to red pandas,” said Holeyachi. For starters, Darjeeling isn’t even their natural habitat, so they cannot be released here.

They would need to be released somewhere in northern Sikkim, Ladakh, or Arunachal Pradesh.

“And training big carnivores for rewilding is very difficult. We need to develop their predator senses over time. I don’t know a single place in the world that is currently rewilding snow leopards,” he added. Categorised as ‘Vulnerable’ by the IUCN, there are barely 6,500 snow leopards left in the wild in the entire world, according to WWF.

The zoo itself remains committed to the survival of all endangered Himalayan species — sometimes even more so than to the red pandas. With its lizard-like appearance, the Himalayan newt does not evoke awws and oohs from visitors the way the red pandas and snow leopards do. It’s no crowd puller, but for the extremely rare and old salamander found specifically in Darjeeling, the zoo built moist and forested areas with terrarium-lined ponds to create a conservation breeding centre. It is an animal that is listed as ‘near threatened’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but the zoo has managed to breed almost 50 of them currently.

“Conservation and science go hand-in-hand. You can’t be selective about conserving species, you need to protect an entire ecosystem,” said Prajwal. “I think we’re doing a pretty good job of balancing the two.”

‘Not a job’

At the centre of the conservation efforts is head veterinarian Joy Dey who has worked at the zoo for almost 10 years. He has a simple approach to his job — don’t treat it as one.

“You [have to] love animals. This isn’t 9-to-5, there’s not much ROI, and it’s not a flashy job. What it needs though is consistent effort and dedication to animals and conservation,” said Dey.

When he noticed that there were very few international official studies that gave a protocol on how to administer anaesthesia to red pandas, he decided to just make one himself. He conducted the study based on the reactions to anaesthesia by all the red pandas inside the zoo, and the ones in the conservation breeding centre, accounting for error points and sample size issues.

“We’re not here to just keep the animals alive in the zoo, right? If we have them, we need to take care of them, their health and well-being,” said Dey.

He’s a reticent man until he starts talking about the animals under his care. In his lab, he gently chided a junior researcher for letting frost accumulate in the freezer used to store DNA samples, but then also showed her how to remove it.

But he’s not just confined to the lab. During the day, zookeepers and guards often see the familiar bespectacled face strolling around the zoo, quietly observing the visitors and his beloved animals.

He’s created a hormonal profile for some species like Himayalan gorals, analysed common gastrointestinal parasites found in the zoo’s captive animals, and studied and recorded the normal haemoglobin levels of captive Himalayan animals. This meticulous research conducted by the Padmaja Naidu Zoo is published online, a treasure trove of Himalayan species out in the open for the entire world to see and use.

Such information is vital, said A Udhayan, the director of the Advanced Institute of Wildlife Conservation (AIWC) in Chennai. There’s a global research gap when it comes to clinical and reference standards of many species. Especially since captive and wild species don’t have similar standards, a lot of information gets lost in translation or just doesn’t get recorded.

“Every vet or wildlife expert has to sometimes improvise the standards they need to work with, but what is important is to record their experience for future use,” says Udhayan. “A lot of zoos and veterinarians just don’t record it, leaving others in their role to start from scratch again. It is just pure initiative through which the Darjeeling Zoo is adding to a global research framework,” he added.

Genetic bank

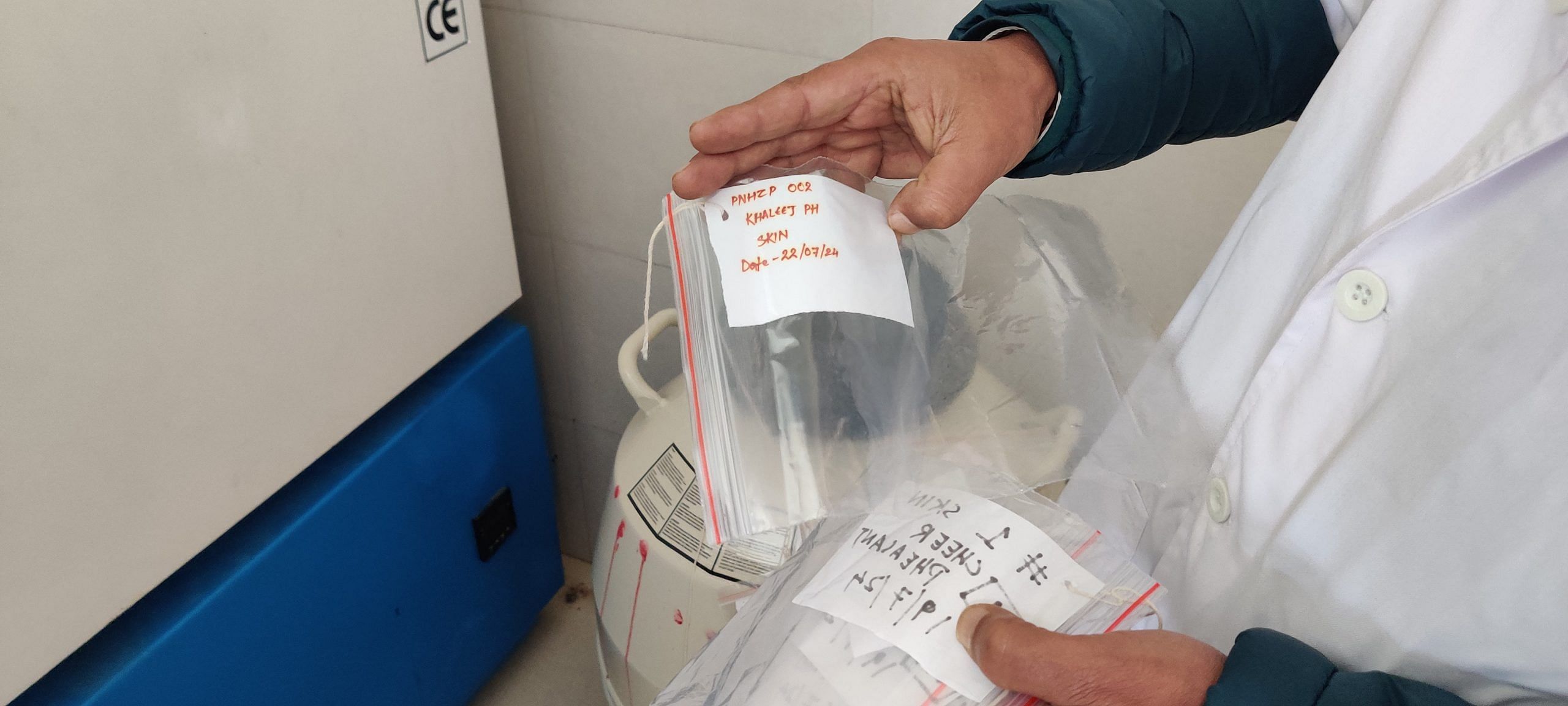

Dey, along with his two assistant researchers and microbiologists, has brought the same enthusiasm to his new role leading the new genetic biobank.

This facility, in coordination with the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), marks a milestone for any Indian zoo. It’s the first time that the genetic material of endangered animals is being extracted, processed and stored inside a zoo.

Down a moss-covered staircase, away from the visitors at the zoo, is a brand new facility equipped with state-of-the-art cryogenic freezers, centrifuges, and spectrophotometers that are all necessary for a biobank facility for genetic material. The most valuable things in this facility, however, are the 21 different DNA samples from 9 endangered Himalayan species that the zoo has been able to store here: Himalayan pheasant, leopard cat, red panda, Indian civet, Himalayan goral, among others.

Holeyachi, who has been closely involved with the genetic biobank facility since they started working on it in April 2024, is buoyed by the work of international scientists using animal genetics. He talks in awe about the recent “IVF pregnancy” experiment using white rhinos in Africa. That is the standard he maintains for himself and the zoo and hopes that Padmaja Naidu’s work is just as impactful.

“God forbid, but in case in the future, there aren’t any more of these Himalayan species like red pandas and tahrs and gorals left, then we at least have their genetic material and can possibly bring them back,” said Holeyachi.

A genetic biobank safeguards the reproductive potential of an animal is not lost.

It is a rich resource for future generations that will make sure that an animal will live even after it dies, said Karthikeyan Vasudevan, Chief Scientist at CCMB, who works closely with Holeyachi and Dey in securing the future of these endangered species.

It’s useful even for animals in the wild and can be used to help identify diseases and pathogens, and study a species’ evolution and adaptation patterns.

Right now, though, the facility is fully engaged in just gathering and maintaining the genetic material of the available species. The DNA of a species is gathered from samples of different tissues, including hair follicles. These DNA samples are stored in a tank filled with liquid nitrogen and can be used to create a genetic profile of the animal.

Donning his gloves, Dey shakes the tank to explain how DNA samples need an exact temperature of -197℃ to be preserved, and how even a drop of this liquid nitrogen can instantly freeze and shatter human skin. The other task of the facility is to preserve the gametes and sperms of endangered animals to create the biobank for future use by scientists.

However, experts like Udhayan caution against viewing genetic biobanks and rewilding strategies as the top-most conservation strategy for any species. While it is a good backup, we should only depend on it if the situation is extremely dire, he said.

“If we have to resort to artificial insemination and rewilding captive species to conserve an animal in the wild, then I’m sorry to say, we’ve already failed at conserving it. To really, truly protect a species we need to protect its existence and its habitat in the wild.”

Back in the enclosure for the red pandas at the Darjeeling Zoo, beady-eyed Swati crawls close to the enclosure wall and the crowd lets out a host of ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’. The zookeeper requests them to back up, to give the pandas space and silence. But one young boy isn’t quite convinced.

“That’s not a panda. Pandas are black and white.” Before the zookeeper could reply, his father intervened. “Those are in China. This is an Indian red panda,” he said beaming with pride.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

How did Mamata Banerjee escape from the zoo? Was she too experimented upon by the scientists at the zoo?

That’s great.

But is there a possibility that Ms. Mamata Banerjee is an experiment gone wrong at the Darjeeling zoo? Or did she escape from the confines of the zoo?