Patiala: Patiala has what is called a mini-zoo. But it has four times the number of animals that mini-zoos are meant to. They’re packed like sardines and on the verge of spilling out. Two endangered painted storks share a half-filled muddy pool with ten other water birds including lesser whistling ducks. And among the 400 other animals in the zoo are vulnerable species like marsh crocodiles and Indian hog deer. What’s worse, all these animals are managed by just one forest guard and three labourers posted by the Punjab Forest Department.

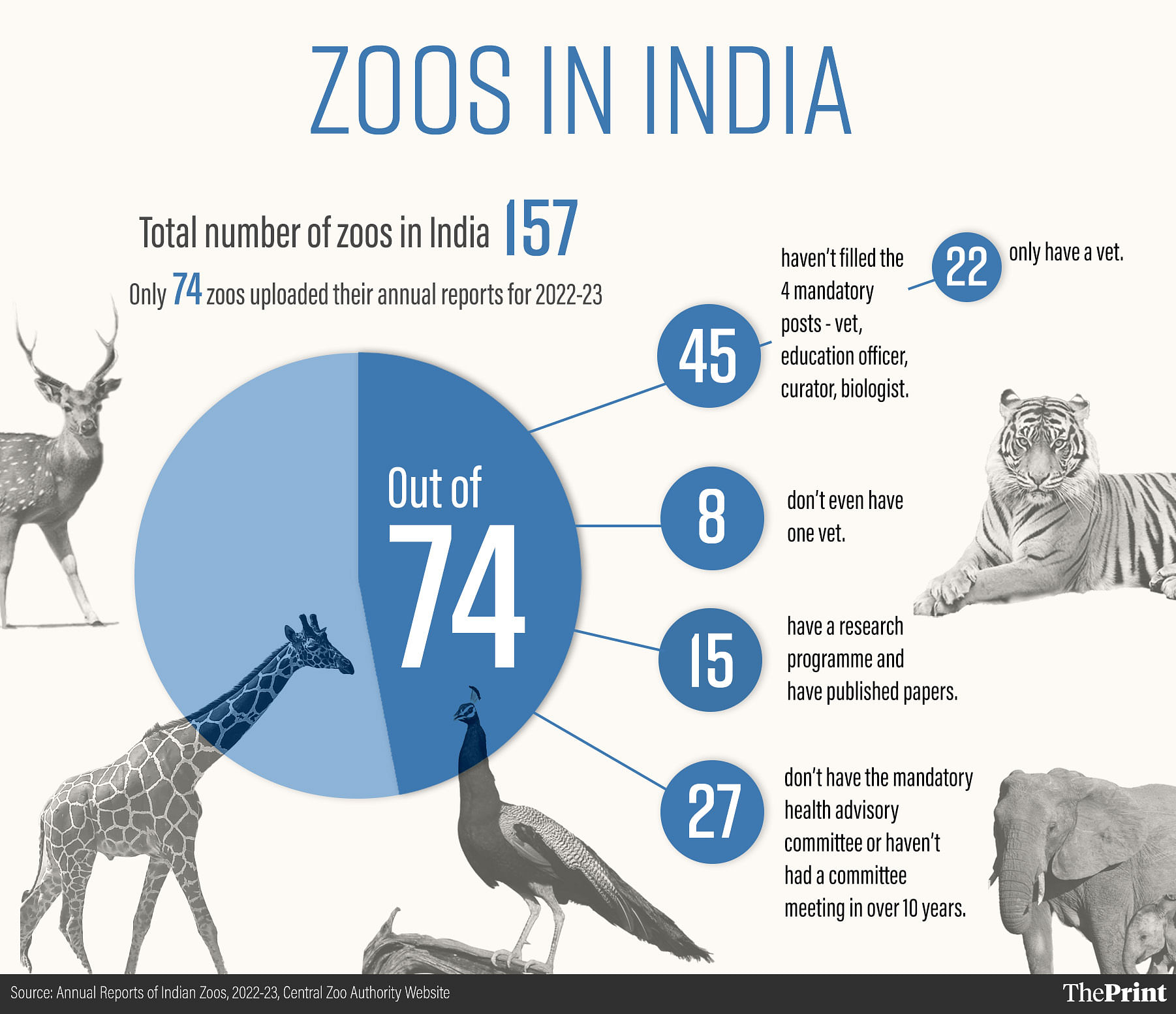

And it doesn’t have an in-house designated veterinarian, curator, biologist, or education officer mandated by the Central Zoo Authority. There is a severe workforce crisis in zoos across India. Of 74 zoos analysed by ThePrint, 60 per cent are understaffed, 36 per cent don’t have a working health advisory committee, and only about 15 of them have genuine research and conservation breeding facilities. All these are flouting Central Zoo Authority guidelines.

As Reliance Industries’ new private Vantara zoo in Gujarat and its Greens Zoological, Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre captivates Indian and global audiences with its stellar facilities and grand scale, the crying gap in Indian zoos has gone largely unnoticed and unaddressed. Vantara is one of the world’s biggest zoos spread across 280 acres and housing 3,000 animals. It also has eight permanent veterinarians, the most in any Indian zoo. By comparison, out of the 74 Indian zoos that have uploaded their annual reports for 2022-23, 10 per cent don’t even have a single veterinarian.

The Central Zoo Authority — the principal organisation on zoos in the country — has a Vision Plan for this decade to transform Indian zoos into pioneers of animal conservation and research. But most zoos in the country are still struggling to meet basic workforce requirements.

Also read: Delhi zoo is now a den of death — a result of politics, apathy and corruption

Classification confusion

Sandeep Kaur, a forest guard by profession, decides everything at Patiala’s Bir Moti Bagh Zoo—from the type of fish given to the marsh crocodile to when the new visitors’ footpath will be paved. “Be it the animals or the visitors, I have to take care of how the zoo caters to both,” said Kaur to ThePrint. But Kaur had no experience dealing with animals before she was posted to the zoo three years ago.

Managing a zoo is serious business…But it is often seen as just another job posting for forest officials

– Shubhobroto Ghosh, Wildlife Projects Manager, World Animal Protection in India

All zoos in the country are run based on the Recognition of Zoo Rules 2009 published by the Central Zoo Authority. According to these guidelines, zoos need four mandatory positions to run effectively— veterinarian, curator, education officer, and biologist, aside from posts like animal keepers and cleaners. The CZA also clearly defines that veterinarians and biologists are responsible for the overall health of the animals, while curators and education officers are supposed to facilitate visitors’ interactions with the animals.

Zoos in India are classified into four categories—large, medium, small, and mini depending on the number of animals and size. For large, medium, and small zoos all the four roles are mandatory, but for mini zoos like the one in Patiala it is just a recommendation. Regardless of the number and kind of animals they have, mini zoos according to the CZA need only have “appropriately qualified officials available locally”. This is the role Kaur fills.

And her circumstances are therefore typical of a number of government-run mini zoos and rescue centres in the country—they’re left in the hands of forest officials posted on deputation, whether they have the expertise required or not. “Managing a zoo is serious business, because it involves dealing with captive wildlife which is different from other animals. But it is often seen as just another job posting for forest officials,” said Shubhobroto Ghosh, Wildlife Projects Manager, World Animal Protection in India and author of the Indian Zoo Inquiry.

Sanjay Shukla, Member Secretary of the CZA, has a reasoning for why mini zoos are exempted from mandatory posting. “Such strict requirements would put an unnecessary burden on them since many are located in areas where qualified officials aren’t readily available,” he said, giving the example of small deer parks and zoos in hilly areas of the country.

ThePrint’s analysis, however, throws a wrinkle into this as it shows that mini zoos are of varied sizes. By the CZA’s definition, mini zoos are those zoos that have an area of less than 10 hectares and have less than 100 animals. But like Patiala’s Moti Bagh Zoo, there are at least 10 other ‘mini’ zoos that are filled beyond capacity, with some like the Garchumuk Deer Park in West Bengal having 1,000 animals.

Their scale and functioning is beyond that of a mini zoo. Based on the number of animals it has, the Patiala Zoo would qualify as a medium zoo. If this change is made then Kaur would not have to perform the role of a curator, biologist and education officer all by herself.

Also read: For love & freedom: Teen wages battle for lonely African elephant at Delhi zoo

Understaffed and lacking talent

Just 70 kms away from the Patiala Zoo is Mohali’s Mahendra Chaudhary Zoological Park also knows as Chhatbir Zoo. It is a ‘large’ zoo and has two designated veterinarians for its 1,800 animals. Every week, the vets check in on the animals. They also get daily reports from the 10 or so animal keepers posted in each section. The Chhatbir Zoo is however an exception, not a rule. In Patiala and many other zoos in the country, there is just one on-call vet from a local polyclinic who visits during emergencies.

“Veterinarians in most zoos learn from experience, as they get a chance to learn from experience gained from their regular contact with wild animals. An on-call vet from domestic animal practice won’t be able to step into the world of exotic animal practice at will,” said Dr NV Ashraf, a senior advisor at the Wildlife Trust of India, who was the chief veterinarian of Coimbatore Zoo for nine years.

This is also the principle behind the CZA requiring mandatory postings. The CZA also requires that every zoo constitute a health advisory committee, which will look into the overall health of the animals as well as advise vets on the hygiene and sanitation of animal housing. ThePrint looked at the annual reports of 74 zoos and found that 36 per cent of them, including mini, small, and medium-sized zoos did not have health advisory committee meetings.

Some zoos had health committees but these committees had either not visited the zoo, or had not met for a single meeting in the last 10 years. Five zoos in total, of varying sizes—Indira Priyadarshini Zoo in Karnataka, Adina Deer Park in West Bengal, Rajiv Gandhi Zoological Park in Maharashtra, Nehru Pheasantry in Himachal Pradesh, and Kinnerasani Deer Park in Telangana—don’t have a full-time vet and have not had a health advisory committee meeting in years.

An on-call vet from domestic animal practice won’t be able to step into the world of exotic animal practice at will

– Dr NV Ashraf, a senior advisor at the Wildlife Trust of India

“There are definitely staffing issues with some zoos; they can’t find full-time veterinarians to take up the position. Sometimes a vet retires or leaves, and then the position would be left vacant because recruitment is also a long process in most public zoos,” said Shukla, who’s an IFS officer. He added that sometimes vets do not want to take up positions in mini zoos or small zoos, thinking it won’t be good for their careers. When zoos are unable to find a full-time veterinarian, they tie up with local veterinary colleges and clinics for emergency procedures.

From Visakhapatnam to Manali to Surat, 80 percent of the zoos that ThePrint looked at are situated in cities and big towns. “Most zoos are in cities, where getting vets to work is not really an issue,” said Ashraf. “But a lot of vets who might have dealt with domestic animals lack experience with wild animals, especially captive wild animals,” he added. “If a vet has never dealt with a snake or a porcupine before, he’ll find it all the more difficult to diagnose and treat it.”

It is not just veterinarians that are responsible for an animal’s health though, biologists and zoo keepers play an important role. Speaking of his own experience at the Coimbatore Zoo, Ashraf said that zoo keepers, biologists and veterinarians have to work in collaboration to ensure proper diet formulation and an enriched life inside the enclosures.

“Take the example of a palm civet. Taxonomically, it is classified as a carnivore so a vet might be tempted to prescribe a meat-based diet for it. But only a wildlife biologist can tell you that actually palm civets eat a lot of fruit, and need little meat in their diet,” he said.

Also read: Cheetah Mitras are the ambassadors of Modi’s Kuno dream. They have been on the frontlines

What is a zoo for?

The Central Zoo Authority was established in 1992 with the mandate of evaluating Indian zoos on how they function and to regulate ex-situ conservation of animals. “At the time CZA was set up, there were over 500 different zoos in the country, and after rigorous evaluation, we shut down and derecognised over 300 of them for bad planning and standards,” said Shukla, who has served as the Member Secretary of Central Zoo Authority since 2022. “Now, there are around 157 zoos, which are assessed every two years based on which they’re either recognised or derecognised,” he added.

Prerna Singh Bindra, wildlife conservationist and former member of the National Board of Wildlife questions the very basis of having zoos in the 21st century as they promote captivity of wild animals. “Global thinking is to move away from zoos, instead of phasing them out, we are constructing bigger, grander zoos. We are facilitating private ownership of zoos which do not have accountability and also brought in place regulations that enable establishment of zoos in forest land,” she said, adding that the need of the hour is to focus effort on conservation and “captive animals have zero conservation value.”

At the time CZA was set up, there were over 500 different zoos in the country, and after rigorous evaluation, we shut down and derecognised over 300 of them for bad planning and standards

– Sanjay Shukla, Member Secretary, Central Zoo Authority

The Central Zoo Authority agrees with Bindra’s line of questioning. It is clear in conveying that any upcoming zoos in India would only be approved if they provide the highest standards of housing to animals, contribute to cutting-edge research on wildlife, and/or educate the public about conservation.

In the past three decades of its existence, CZA has tried to elevate the standard of Indian zoos through requirements such as master plans and proposals for conservation breeding in zoos to ensure they contribute to the cause of conservation. There are a handful of zoos that the CZA itself has evaluated as ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘requires substantial improvements’ based on parameters such as planning, resource availability, conservation, research activity, and visitor enrichment. In 2022, only Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park in West Bengal, Arignar Anna Zoological Park in Tamil Nadu and Sri Chamarajendra Zoological Gardens in Karnataka, were ranked 80 per cent and above on these grounds. They’re three of the five zoos that have been given a ‘very good’ rating.

Ghosh who has traveled and analysed zoos both in India and abroad talks about the role of zoos in conservation breeding. “Zoos should help breed endangered species and then return them to the wild when possible,” he said. “It can’t just be a place to keep animals indefinitely – that neither contributes to wildlife nor education.”

Take for example, the pioneering Madras Crocodile Bank Trust established by the ‘Snakeman of India’ Romulus Whitaker and his ex-wife Zai Whitaker. In 1976, when the Trust was established, crocodiles were extremely endangered in the Indian subcontinent. Whitaker initiated a programme to breed different crocodile species. And rather than showcase them for recreation, MCBT ‘restocks’ them in the wild—their original habitats.

“We brought reptiles into the ambit of conservation,” said Zai Whittaker to ThePrint. “Earlier, it was just a bird and mammal centric space.”

Apart from having the CZA-mandated number of officials, the Trust contributes to education and awareness programmes not just for school students but also for fishing villages in Tamil Nadu on crocodile and reptile habitats. It boasts of over 690 animals, and just in 2024, it transferred at least 400 crocodiles to other zoos. The Trust, which has a ‘good’ rating, is an ideal model for zoos to follow—its operation benefits both the people in the area and the animals.

Zoos should help breed endangered species and then return them to the wild when possible. It can’t just be a place to keep animals indefinitely – that neither contributes to wildlife nor education.

– Shubhobroto Ghosh, Wildlife Projects Manager, World Animal Protection in India

Bindra said that the number of zoos engaging in this form of conservation breeding “can be counted on one hand”. And only 15 zoos analysed by ThePrint that mention any sort of research or conservation breeding in their annual reports. The nature of research in most Indian zoos is also contentious according to Ghosh. “Any genetic or behavioral research conducted on captive animals might not be applicable on wild animals, so the purpose of this research is limited,” he said.

Also read: Tourist rush into a sleepy Tamil Nadu town causing wildlife roadkill. 2 ecologists helping

The future of Indian zoos

Shukla, the Member Secretary of CZA, is aware of the shortcomings in Indian zoos—both in staffing and in their vision plans. He is aware of the need for zoos to independently engage in capacity-building programmes, workshops, and training for its personnel. The CZA provides a limited number of workshops for biologists and veterinarians, but it also asks zoos to continually invest in the skill development of their workers.

It encourages inter-zoo collaboration and public-private partnerships in managing zoos. Shukla underlined its Vision Plan 2021-31 as the guiding document. It proposes everything from meticulous biologist records, conservation education plans, and international collaboration for breeding programmes. Unless Indian zoos are able to embrace this challenge of scope and vision, they will remain, in the words of the CZA, just “ad-hoc animal collections for public recreation”.

Some zoos have risen to the challenge, and are attempting innovative ways to stay relevant and attract visitors of all ages. Delhi’s National Zoological Park, for example, has started an ‘animal adoption programme’ that lets visitors adopt an animal and pay for its care and maintenance. It boosts the zoos’ incomes and allows them to upgrade facilities and upskill their workers, while also encouraging the general public to take a deeper interest in wildlife. In an electric caddy outside the director’s office, a man and his young daughter wait holding an application form. “She really likes spotted deer, especially after watching Bambi,” said the man. “We’re going to adopt a Bambi when I turn eight this April!” the daughter added, with an excited smile.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)