Darbhanga/Deoghar: It’s not mountains, monuments, or monasteries that populate Deepak Yadav’s Instagram handle, but photos and reels of Darbhanga airport, aeroplanes, fellow passengers, takes–offs and landings—all set to Bollywood songs like Lata Mangeshkar’s Jab Se Mile Naina. The sales agent who lives barely three kilometres from this small-town airport in Bihar is proud of his new jet-setting lifestyle. He has ‘arrived’. His little town is on India’s aviation map, and he wants everyone to know it.

“It was my dream that wherever I travel, it would be on a plane. And now, I only fly,” says Yadav in a reel. Since Darbhanga airport became operational in 2020, Yadav has been flying to Delhi and other cities instead of taking the train or a bus to sell agricultural products like fertilisers. He has watched the town grow—there’s now a cafe, sprawling warehouses, a start-up incubator, several residential and commercial projects, and a steady flow of people in suits and saris coming to Darbhanga. The town, famous for makhana, fish, and paan, is now attracting tourists, business persons, and entrepreneurs. And unlike AIIMS-Darbhanga, which remains a status symbol on paper, the airport has taken off.

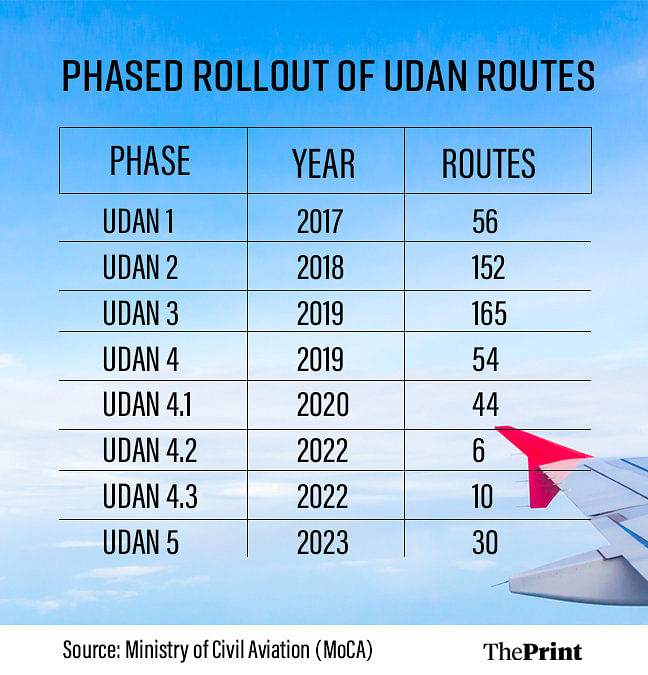

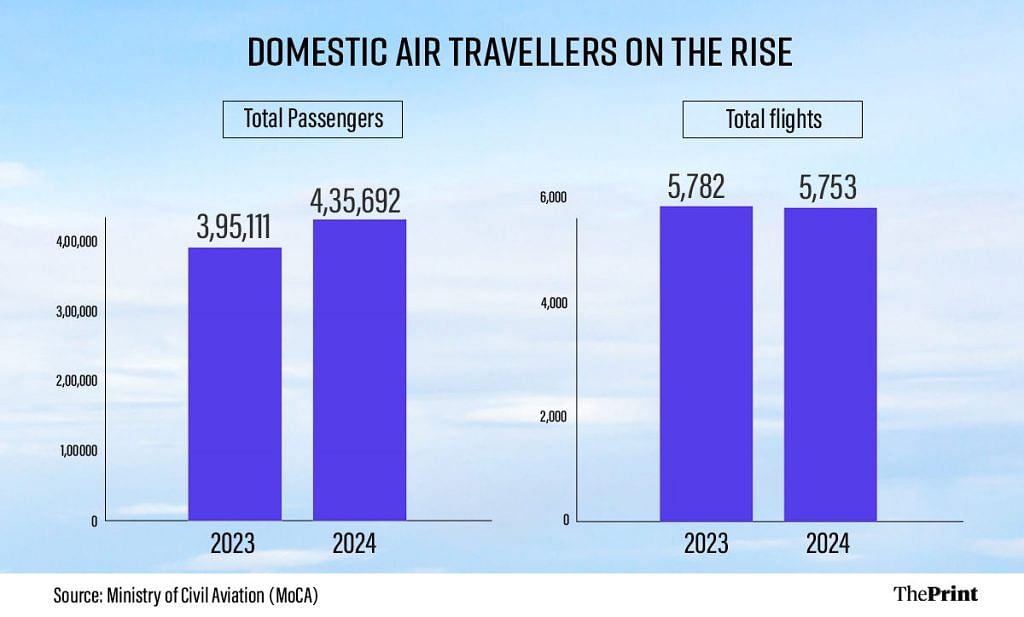

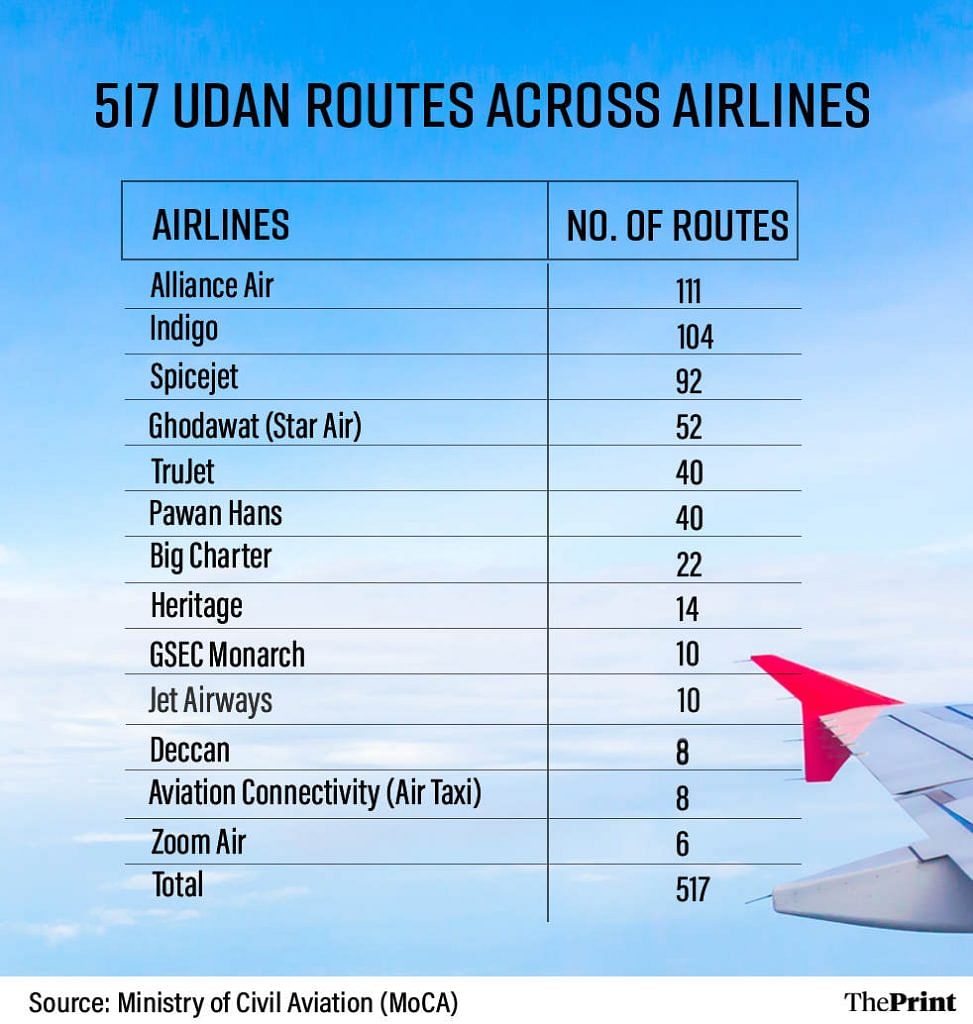

It’s all part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious 2016 scheme UDAN—Ude Desh ka Aam Nagrik—which has introduced 517 operational flying routes and 76 airports in the country’s small towns and cities in the last seven years. He wants to see people who wear “hawai chappals” fly on the “hawai jahaz”. Last year saw a record number of domestic travellers—between April and November 2023, more than 20 crore passengers took to the skies, a 120 per cent jump since 2014. But poor infrastructure (Darbhanga doesn’t have an instrument landing system), a turbulent aviation sector (Go First crashed and burned in 2023), and rising ticket costs are putting a brake on the PM’s dream.

UDAN is central to the Modi government’s plan to boost tourism, promote trade, and empower local economies. Airports in far-flung parts of India—Pakyong in Sikkim, Kannur in Kerala, Bareilly and Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, Jharsuguda in Odisha, and Hollongi in Arunachal Pradesh—which could once only be accessed by rail or road, are changing the way people travel. This year opened with Goa getting a second airport at Mopa, while the newly launched Maharishi Valmiki International Airport in Ayodhya is bracing itself for heavy traffic ahead of the consecration of Ram Mandir on 22 January.

The airports have ushered in a new era of labour mobility, tourism, and small-town aspirations poised for an economic boom. Hotel chains like the Tata Group’s Ginger, Lemon Tree Hotels, the Radisson Hotel Group, and others are looking at Tier-II cities for growth. Litchis from Muzaffarpur and makhana from Mithila are flying across land and oceans, connecting national and global markets.

“The last nine years have been transformative for India’s aviation sector. Existing airports have been modernised, new airports have been built at quick pace and record number of people are flying. This enhanced connectivity has given a big impetus to commerce and tourism,” Modi had tweeted last April, responding to a post on UDAN by the Ministry of Civil Aviation.

However, aviation experts like Mark Martin, who runs a consultancy, raise doubts about UDAN’s sustainability. Only 7 per cent of routes under the UDAN Regional Connectivity Scheme are sustainable after the three-year government subsidy period, according to a 2023 CAG report.

“The fundamentals of this scheme are flawed—the number of non-viable airports is increasing. Viability cannot be achieved overnight. It takes many years to see the growth pattern,” Martin says.

Nevertheless, for the Indian traveller eager to take to the skies, the airports come with the promise of time saved.

“It used to take 15-18 hours to reach Delhi but because of the airport, I now reach my destination in a few hours. There is nothing more valuable than time in business,” says Yadav, who is attending an annual conference in Delhi. He’s careful not to crease his brown suit, which he’s paired with a black tie.

Passengers exiting Darbhanga airport stop by a woman squatting some 30 metres away selling fish. Others scarf down litti-chokha before entering the terminal. Airports are the new railway stations.

“After the Modi government came to power, domestic flights were looked at from the perspective of tourism, commercial and economic growth. A lot of financial impetus has been given over the past 10 years,” said aviation expert Vipul Saxena. “Currently, RCS operations are supported through government subsidy because it has not been economical for the airlines operating bigger aircraft so far. Recent policy by MoCA of promoting smaller aircraft and helicopters will make RCS model financially viable,” he added.

While the government has awarded 1,154 routes to 13 operators under the UDAN scheme, only 517 routes were actually operational as of 27 December 2023. And though domestic air travel has increased, services on many routes under UDAN have stopped.

Chai, take-offs, and a few bumps

Young men and women chug down cups of tea and munch on paneer tikka at Baithak Cafe, less than 20 metres from Darbhanga airport, while clicking photos of planes landing and taking off. It’s a popular spot not just for passengers but for local residents as well.

On a cold December evening, Rishi Kumar from Keoti village, about 15 km from Darbhanga city, sits with 10 of his friends, strumming one of the two guitars that cafe owner Raj Prasad keeps out for customers. “This cafe opened only after the airport started. Earlier we had to go further away if we wanted to go out,” Rishi says. The cafe, which has an outdoor seating area, serves everything from lemon soda to meat and non-meat dishes.

While Baithak Cafe exudes charm, Darbhanga airport is chaotic. The number of passengers increased from 1.53 lakh in 2020-2021 to 6.17 lakh in 2022-23. As the sole airport in north Bihar, it’s one of the busiest under the UDAN scheme, beating even Patna airport. With only a few trains from Darbhanga to Delhi—people either have to go to Patna or travel 100 kilometres to Saharsa to catch a train—the airport cuts down on travelling time by days. Two carriers, IndiGo and SpiceJet, operate out of Darbhanga with flights to Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Kolkata.

Until a few years ago, people were scared to come here. Now, it’s buzzing

-Prashant Jha, hotel owner in Darbhanga

A tin shed above the departure point serves as the waiting area for passengers. There’s a serpentine queue at the lone entry point into the airport. Men, women, and children in jackets and sweatshirts, almost all wearing sports shoes, clutch their Aadhaar cards. “Where have you come from? Where are you going? What time is your flight?” they ask each other in Maithili. Unlike a train journey, where travellers prioritise comfort over style, people are more formally dressed for air travel. But nobody compromises on food—many have packed thekua and balushahi in jute bags. One passenger forks out Rs 600 for the extra kilogram of food in his bag.

Inside the terminus, uniformed staff in skirts or trousers and jackets at the lone baggage check-in counter are harried and overworked, while a crowd gathers at the security check-point. “Please maintain a queue,” says a SpiceJet employee in Hindi as an impatient passenger tries to cut the line. Two flights—one to Mumbai and another to Delhi—are due to take off. The Mumbai flight is prioritised.

Shambhu Yadav, who works at a cloth factory in Gandhi Nagar in Delhi, earning Rs 12,000 a month, settles in for the wait. He had taken leave to come to Darbhanga when his father’s health took a turn for the worse. A train would have taken too long, so he shelled out Rs 6,000 to fly to Delhi. “Half my salary was spent on the ticket, but I got to see my father before he passed away,” he says.

After security, passengers are ushered into the waiting area—an open space under a tin roof with a little over 40 seats. Like the rest of the small terminus, it is not air-conditioned. As they wait, passengers crane their necks to look at the planes.

Given the large number of out-migrants from Darbhanga and its surrounding districts, the airport has been a boon, especially when emergencies arise at home, says Gopal Jee Thakur, BJP leader and MP from Darbhanga. “It used to take a lot of time to reach here. Today, with the airport, people arrive within 2-3 hours,” he adds. A former director of Darbhanga airport, requesting anonymity, points out that people from Nepal use the airport as well.

The airport, however, has been around for a long time. Built by Kameshwar Singh, the erstwhile maharaja of Darbhanga, in 1950, it is, in fact, one of the oldest airports in Bihar. The enterprising maharaja also launched a private carrier, Darbhanga Aviation, but it shut down in 1962. The airport was reportedly taken over by the Indian Air Force during the war with China.

This is a common trajectory for UDAN airports—only 11 out of 76 are entirely new constructions. The rest were existing defence or defunct airports that were revived. The government has plans to strengthen the runway, expand Darbhanga airport with a permanent terminal building on 54 acres of land, and install an instrument landing system (ILS) to facilitate landing at night and during bad weather. But construction has yet to begin.

For now, passengers have to make do with the existing facilities. Dr Sohail Ahmed, who has to attend a wedding in Mumbai, has been told that his flight will be delayed by two and a half hours. He’s worried he’ll miss the main event. “Maybe I should have just taken the train,” he mutters while looking for a place to sit. All the seats are occupied.

The once-deserted area around Darbhanga airport—2 km from the city—has transformed over the last few years. No longer the boondocks of Bihar, the place has morphed into a busy area with hotels and restaurants.

Also read: 2 clerks, 1 director, 1 room—AIIMS Darbhanga a story of political rush to announce…

First real estate, now litchis, next makhana

North Bihar is a blind spot on India’s tourism map, but there’s hope that Darbhanga airport will open new opportunities for travellers.

The once-deserted area around Darbhanga airport—2 km from the city—has transformed over the last few years. No longer the boondocks of Bihar, the place has morphed into a busy area with hotels and restaurants.

“Until a few years ago, people were scared to come here. Now, it’s buzzing,” says Prashant Jha, who owns a hotel located around 200 metres from the airport. Business is good, and the hotel’s 12 rooms are almost always booked. Most of Jha’s guests are investors and business persons looking for property and opportunities to cash in on the airport boom. A start-up incubator has also come up in collaboration with Darbhanga College of Engineering.

“People aren’t only returning now to meet with their families in villages. They also want to come and work here,” says Arvind Jha, a software engineer from Madhubani district. He used to visit his village occasionally, but since the airport opened, he flies home several times a year.

In the last few years, many townships and warehouses have come up around the airport, with land prices doubling. Since 2020, more than 15 real estate companies have set up shop in Darbhanga, says property developer Rajan Thakur, who runs a private residential township, Shri Ram Janaki. To date, he has sold land to 150 people within a 10 km range of the airport.

Most buyers are from neighbouring districts, but people from outside Bihar are also taking land here for business purposes, says Thakur. “Before the airport, the price of land here was Rs 6-7 lakh per kattha. It is now Rs 14-15 lakh per kattha. Due to the airport, transportation, business, and medical facilities have become easy [to access],” he adds.

And he’s not the only one cashing in on this new economic growth. The private taxi sector is also booming. Dilkhush Kumar, CEO of cab service company RodBez, allocates more drivers to Darbhanga now. “Lifestyles are changing and people who use flights have started using taxis,” he says.

Even farmers haven’t been left behind. The introduction of cargo flights has opened new avenues for their produce. At present, litchi is sent out of Bihar from Darbhanga airport, with 300 tonnes of the fruit exported in the last three years. However, cargo flights only run for around two months a year during peak litchi season.

Krishna Gopal, the marketing and policy head of the Litchi Growers Association of Bihar, representing over 2 lakh farmers, advocates for year-round cargo flights.

“Due to flights, the goods reach quickly and remain fresh. This is an advantage, but the cargo facility is available for a limited time and only for litchi,” he says.

The central government’s Krishi Udan Scheme, launched in 2020 to facilitate transport of agricultural produce on international and national routes, currently covers 58 airports. But farmers and traders like Gopal say the scheme is not being explored to its full potential in Darbhanga.

North Bihar is famous for makhana and fish, but only seasonal litchi is being exported right now. “There is enough opportunity for income here but there are no facilities,” says Gopal.

The lack of basic infrastructure—air conditioners, sufficient seating, display boards, and eateries within the terminal—is a sore point among passengers.

Small-town airports, big challenges

Darbhanga-based journalist Manikant Jha waxed eloquent about the airport in his book Udan: A Journey Translated. “The airport was primarily a place where I watched planes land and take off. It was a far cry from what it has become today, bustling with passenger airlines. It’s fascinating to reflect on how this airport has evolved,” he wrote.

However, there is also a growing litany of complaints.

On 15 December, Digambar Kumar reached Darbhanga from Madhepura after travelling about 100 km in a public bus. When he arrived at the airport at 10am, he was informed that his flight had been delayed by four hours. This has become something of a norm. According to data compiled by Flight Era, 67 per cent of the flights serving Darbhanga airport—around five a day—are delayed.

“I booked a flight from Darbhanga to cut down on an additional 4-5 hours of train travel to Patna. But the flight got late and I wasn’t even informed on time,” Kumar grumbles while eating litti-chokha outside the airport gate.

The lack of basic infrastructure—air conditioners, sufficient seating, display boards, and eateries within the terminal—is a sore point among passengers. “Any city’s bus stand is better than this. We have been standing outside for hours, there is no arrangement to even sit here,” says Nitesh Choudhary from Motihari, who had to catch a flight to Bengaluru.

It is a newborn baby. Starting an airport and running it are two different things

Praveen Kumar, director of Deoghar Airport

There are times when flights from Delhi to Darbhanga are diverted to Patna due to bad weather or technical glitches.

An ILS would ease the delays and allow flights to take off and land at night, but even after three years, the system is yet to be installed.

Frequent flyers lament the lack of upgrades to the airport over the past three years. Another common complaint is that the ticket prices are unaffordable for labourers and migrant workers. During the wedding season and Chhath Puja, air tickets from Delhi to Darbhanga can cost between Rs 15,000 to Rs 20,000. “We are constantly talking to the airline company to keep the prices reasonable,” says Thakur. He also petitioned the state government for land to expand the airport. While 76 acres of land has been granted, the tender process has only just begun. “A tender worth Rs 916 crore has been issued,” says the BJP MP.

The problem of rising fares is not limited to Darbhanga alone. The CAG, in its August 2023 report, called for a revamp in the booking of seats on regional routes to ensure that airline operators do not charge more than the cap stipulated in the government’s Regional Connectivity Scheme.

“Inter-regional disparity is very high in Bihar and the per capita income is also very low. Therefore, only people who earn well use more air travel,” says DM Diwakar, the Madhubani-based former director of the AN Sinha Institute of Social Studies.

The irony is that while domestic air travel has increased, services on many routes under UDAN have stopped. Darbhanga airport, like Deoghar, Surat, Hubli, and Mysuru, are the few that buck the trend. As of 31 October last year, 103 regional connectivity scheme (RCS) routes were discontinued after three years, and another 136 routes were terminated before completing the three-year subsidy period, Minister of State for Civil Aviation VK Singh had told the Rajya Sabha.

Central government data shows that eight domestic airlines have folded in the past five years, including Go Airlines, Air Deccan, Air Odisha, and TruJet. Of these, TruJet was running operations on 40 RCS routes. While the government has awarded 1,154 routes to 13 operators under the scheme, only 517 routes were actually operational as of 27 December 2023. The finance ministry doubled the outlay for UDAN from Rs 601 crore in the last financial year to Rs 1,244 in 2023-2024.

Also Read: Ayodhya is being rebooted, rebuilt, & reimagined— Gen Z pilgrims, luxury hotels, 3D shows

Boosting religious tourism

Through UDAN, the government wants to cash in on the lucrative temple corridors and religious tourism, which, according to market estimates, was valued at around $56 billion in FY2023, up from $44 billion in 2020. Less than a week from the consecration of Ram Mandi, air tickets to Ayodhya’s newly opened airport are going at three times the usual rate.

The government claims that the tourism industry in the entire Northeast is experiencing a considerable upsurge due to the introduction of Pasighat, Ziro, Hollongi, and Tezu airports. In the last six years, 53 religious routes were awarded under the RCS scheme, including Khajuraho, Amritsar, and Kishangarh (Ajmer).

While Ayodhya airport isn’t part of UDAN, Deoghar airport in Jharkhand stands out as a success story in the religious circuit, and is more upscale than its counterpart in Darbhanga. Famed for the Baba Baidyanath Dham, Deoghar is no stranger to VIP visits, from Lalu Prasad Yadav and Rabri Devi to Home Minister Amit Shah, who flew from Delhi in February last year. It’s also a popular base for Parasnath, a Jain pilgrimage site around 50 km away. Now, the town is set to host a replica of Tirupati’s Balaji Temple, further amping up its religious appeal.

Already, lakhs of people come to Deoghar every year, especially in July-August, making the airport a viable hub for those on the religious circuit. But the airport does not have an ILS facility, and is only being serviced by Indigo Airlines as of now.

“The airline has a monopoly, so ticket prices are high. When more airlines come here, fares will automatically reduce. And then the common man will also be able to travel by air more and more, which is not happening at present,” says Praveen Kumar, director, Deoghar airport.

Given that the airport covers six nearby Jharkhand districts and is easily accessible from parts of Bihar and West Bengal, it could play a key role in Deoghar’s economy, said a senior official of the district administration.

“Earlier, people used to go to Ranchi and take flights but now a lot of time is being saved. And people are also paying more attention towards convenience. It (the airport) will expand further in future,” he added. The official also expressed hope that the airport would attract industrialists. “Due to easy connectivity, companies will start coming here,” he said.

Spread over 654 acres, Deoghar airport, which is 12 km from the city and became operational last year, draws from the city’s religious and tribal history. The airport’s interiors showcase local tribal art and handicrafts, while the facade has carvings of the Baba Baidyanath Dham shikhar. Similar to Darbhanga airport, it is now a local tourist attraction.

On a mild December afternoon, Mohammad Siraj Ansari, a resident of Madhupur, 30 km away, arrived with his brothers—not for a flight, but to soak in the airport’s ambience. “I’ve been wanting to come here for a long time,” he says, taking video clips and photos. “I had heard about the airport from everyone; today I saw it. It’s beautiful.”

After landing at Deoghar from Delhi, Manoj Kumar and his wife Sudha took a taxi and went straight to Baba Baidyanath Dham, one of the 12 Jyotirlingas in India. “I wanted to worship here for many years. But it takes around 17-18 hours by train. When the airport started, we were very happy,” says Manoj, an engineer in Noida. As they stand in a long queue, devotees chant Bol Bam while the couple folds their hands in prayer.

They are returning home the next day, but are not sure if the flight will be on time. Deoghar airport, too, is plagued with delays and cancellations.

“It is a newborn baby,” says director Kumar. “Starting an airport and running it are two different things.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)