Rohtak: Peace died in Karor village on Diwali afternoon. Two men on a bike fired bullets in the air in front of a temple on Sunday, 12 November. “Chajju’s family is still alive. We are not over yet. We will see each of you,” one of them said before zooming away in a cloud of dust, according to eyewitnesses. Moments earlier, Mohit Kumar, an informant for the rival Chippi gang, had been gunned down barely 150 metres away.

A dreaded Jat gang, minted in the crucible of Haryana’s prohibition, panchayat capture, and land grabbing nearly 30 years ago, has resurfaced this month. And now, the murders have resumed as the blood feud between the Chajju and Chippi gangs picks up where it had left off.

The former’s founder Chajju Ram is dead. Anil Chippi, the head of the rival outfit, is in jail. But a Gang of Wasseypur-style generational crime drama, which played out for more than ten years from 1998, is back. This time around, it’s the grandsons who seem to be leading the charge.

Everything about the blood-spilling crime drama is a mystery. Why Karor grew into a lone island of endless violence in Rohtak, how it went on unchecked for decades, and how in this era of smartphones and viral videos this escaped the nation’s and even Bollywood’s attention.

He ran for his life but the gang fired indiscriminately. At least a dozen bullets were shot at him and he finally collapsed

– Rajender, victim Mohit Kumar’s neighbour

During farmer-turned-gangster Chajju Ram’s reign of terror, carried out alongside his seven sons, 19 people died in Karor. Kumar is number 20. He was out on bail after being arrested in connection with the 2018 murder of Chajju Ram’s youngest son.

And then Diwali came and the festival of fireworks took on a new meaning. Now, villagers are on edge, the police are tense, special teams have been deployed, and everyone is dreading yet another era of bloodshed.

A massive three-story house that Chajju Ram built is a reminder of his hold on the village. It is deserted, the paint peeling from its walls. Of his seven sons, five were killed by the Chippi gang, one died of natural causes, and one is in prison. His grandsons don’t live there either, but they have taken over the family’s bloody legacy.

Karor is enacting a generational drama that carries on revenge much like the ‘baap ka, dada ka, sabka badla lega’ line from Gangs of Wasseypur.

Also Read: Sand miners are the new narcos. Rajasthan gangs offer cash, career, swag

A ‘tradition’ of deadly Diwalis

The six bike-borne killers didn’t care who saw them when they roared up to Mohit Kumar’s neighbourhood and fired 40 bullets, 12 of which hit him, according to the FIR. Two of the assailants then announced their deadly accomplishment at the village temple.

“It was Chajju Ram’s grandson who fired the shots,” alleges a woman from Karor. She was sitting on the verandah of her house near the temple when the two bikers rode in.

She and the others fled to their homes while the men peeped fearfully from the windows. “It was Deepak and Malkit,” another woman pipes up, naming two of the four grandsons of the long-dead Chajju Ram. “It was a revenge killing,” says a third woman.

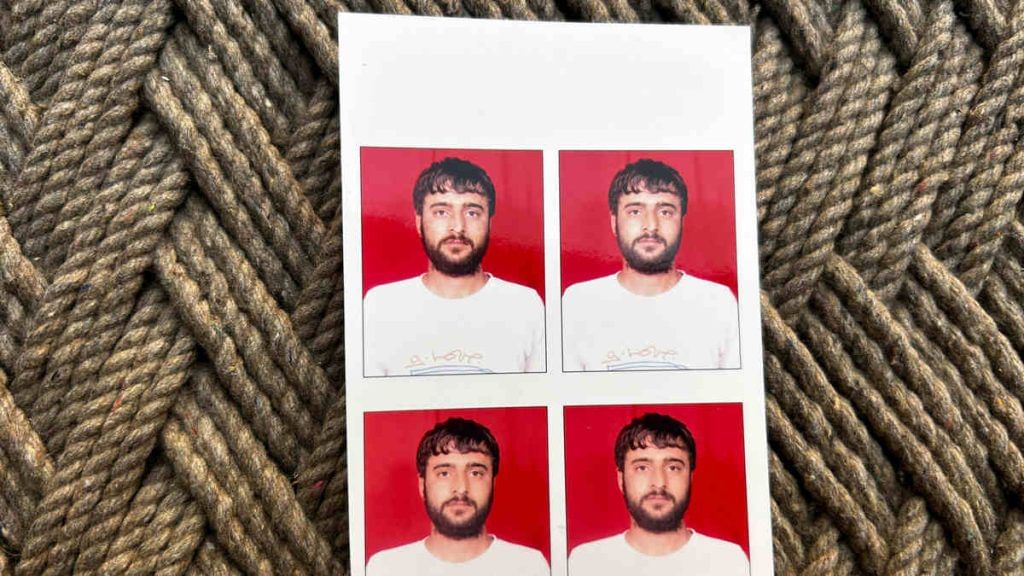

The victim, Mohit Kumar, is alleged to have provided information on the whereabouts of Anand Malik, the youngest son of Chajju Ram, who was shot dead in 2018, allegedly by the Chippi gang. The police have named two of Chajju Ram’s grandsons, Jatin and Malkit, as the ‘prime accused’ but they are on the run. Of the four others named in the FIR, two men have been arrested.

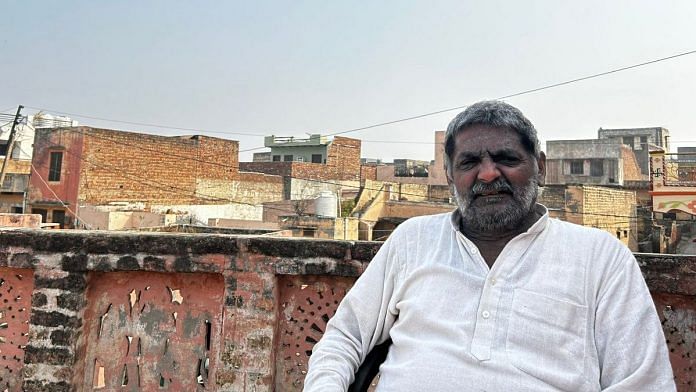

“I have written to the home minister and district administration. The social boycott of these criminals will not work as they don’t care about it,” says the agitated 52-year-old village head Mahipal Singh.

He called a four-village panchayat of the Malik gotra to discuss the ‘return’ of the gang after Mohit was killed— the first since the mid-1990s when 84 villages gathered in a mahapanchayat to hold the gang to account for forcibly taking land from a Jat farmer.

For ten years, Chajju Ram’s family terrorised villagers. He and his sons were accused of robbing retired soldiers of their pensions, driving people away from their ancestral homes, seizing land at gunpoint, capturing panchayat elections, murdering rivals, supplying other gangs with arms, and forcing Dalits into bonded labour.

Karor village, less than a half-hour drive from Rohtak, turned into a no-go zone because of the escalating violence. People from surrounding villages like Kharawar, Pahrawar, Chuliana Duhan, Dighal, and Khedi Sadh steered clear, even though they had seen their own share of gangsters.

Even a small thing such as not giving way on the road can lead to a murder. This gang-lord pride is about manliness, and they execute it in the smallest instances

-V Kamaraja, former IG of Rohtak range

Diwali was when the gang often chose to flex its muscles. In 2008, they allegedly opened fire and killed two women on the day of the festival. It was then that the state’s law and order machinery turned its gaze on Karor.

Retired IPS officer V Kamaraja who served as inspector general (IG) of the Rohtak range between 2008 and 2011 dedicated an entire chowki of 15 policemen to bring the gang down.

“There was not enough mobilisation against this family due to threats and fear, so we had to dedicate an entire team to this village, which was engulfed by crime,” said Kamraja. Rohtak range, he added, was besieged by “too many murders”.

But there has been a shift after the latest murder. The villagers are fighting back. Instead of cowering, they are demanding police action, holding panchayats, and rallying behind the victim’s family.

Mahipal Singh has seen the damage inflicted to the village during the height of the gang war. “I will not let it happen again,” he says.

The rise and rise of Chajju Ram

Chajju Ram was once a humble farmer with just eight bighas of land — not enough for his seven sons and two daughters. Then, in the mid-1990s, Haryana’s brief experiment with prohibition became his ticket to a lucrative bootlegging business. Over the years he expanded his criminal portfolio.

“He was a nuisance even before he became a grand gang lord,” says Chaudhary Jagdish Malik, a former village head.

“The family got into the illegal liquor trade when the Bansi Lal government brought a policy of complete prohibition in 1996,” he adds. “It was lifted in 1998 but in two years, Chajju Ram emerged as a local power.”

During election season—panchayat, assembly, and even Lok Sabha elections—politicians across parties would always make it a point to visit Chajju Ram, claim some villagers.

The truth is that the gang could wipe out an entire family

Kuldeep Malik, farmer

Samundar Gahlawat, 52, a resident of Khedi Sadh village, recalls an incident from the 2005 assembly elections, when the BJP’s Naresh Malik and the Congress’ Chakravarti Sharma were battling for Rohtak’s Hassangarh seat.

“The Chajju gang sided with Chakravarti. So, when Naresh Malik reached Karor’s chaupal (panchayat building) for the election campaign, the Chajju gang locked the gates and chased Naresh out of the village,” claims Gahlawat, whose father was friends with the patriarch of the Chajju family.

Jagdish Malik, who is in his 80s, recalls the time his family, like many others, was terrorised and blackmailed into compliance by the gang. Another village elder, Sant Malik, recalls three mahapanchayats being called in the mid-1990s, when Chajju’s sons allegedly refused to pay Rs 2.65 lakh to a Jat farmer after taking over his land.

“The Chajju family was asked to pay the amount, or else they would be thrown out from the caste,” says Sant Malik.

But, according to him, this threat made no difference to the family. “They responded saying, ‘Jaat se bahar fenko, ya chhat se neeche (throw us out from the caste or from a roof), we will not pay.”

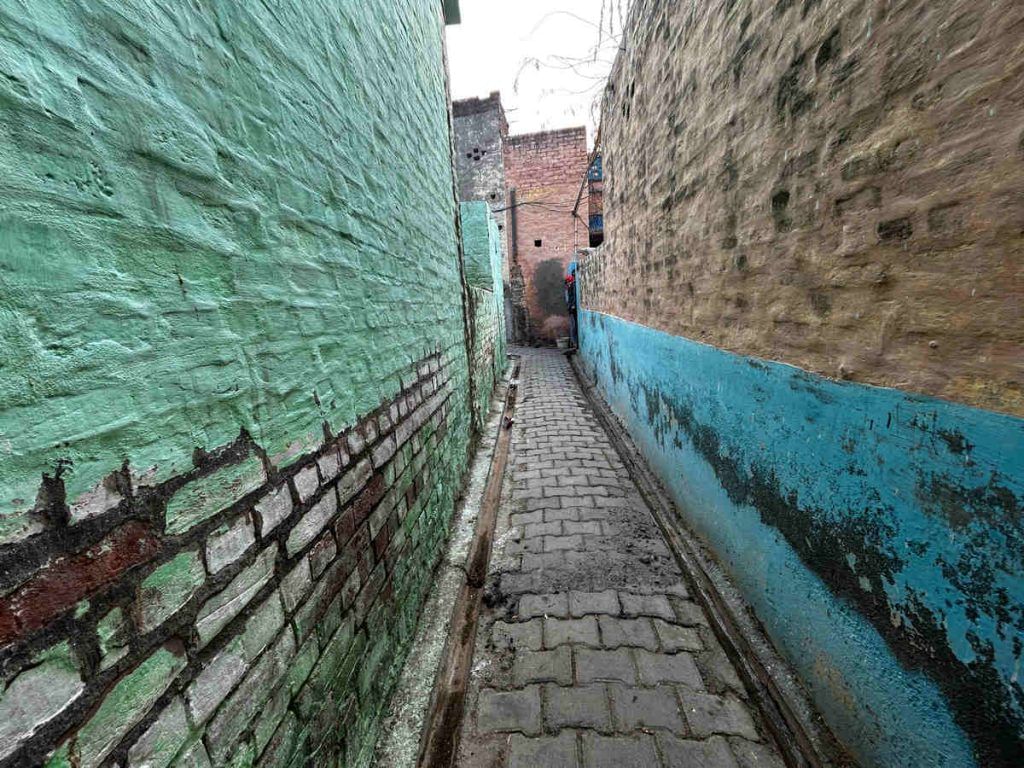

Residents from neighbouring villages began avoiding Karor, fearing they might be beaten up. Bhambewa villagers stopped crossing Karor to reach Kharawar Railway station and instead took the longer route or went to another railway station.

Tongues started wagging that the men of Karor were too cowardly to stand up to Chajju and his gang. But Kuldeep Malik, a 42-year-old farmer from Kharawar, acknowledges that fighting was not an option. “The truth is that the gang could wipe out an entire family,” he says.

With a population of around 5,000 residents, mostly Jats, and fertile wheat fields, Karor is not a poor village. But there is an air of defeat around it. All the houses are cement constructions, but most are in varying states of disrepair, with barely a fresh lick of paint in sight. The panchayat building is dilapidated and the streets are often waterlogged.

“No houses were built or repaired between 1998-2008 in Karor village,” says Sant Malik.

Villages refrained from constructing new buildings or spending conspicuously for fear that it would put them in Chajju Ram’s line of sight.

The sense of intimidation ran deep, not just because of Chajju, but also his sons, who were trained wrestlers and not hesitant to use their akhada-honed skills on villagers who defied them.

“No one would dare challenge a family with so much muscle power,” says Jagdish.

Sant Malik recalls that Phool, one of the brothers, fashioned himself after Katiya, the Bollywood villain from the 1996 Sunny Deol hit film Ghatak — a character who terrorised a colony in Mumbai with his six brothers.

Jagdish says the police arrested Chajju and his sons on many occasions during the 1990s, but then they stopped coming as frequently until the terrible Diwali of 2008 when the gang allegedly murdered the wife and daughter of the village’s largest landowner.

In Karor, where an eye-for-an-eye and a tooth-for-a-tooth is almost a motto, villagers do not want another decade of murders. They want peace

The 20th murder

For 50-year-old Ajit Malik and his wife Geeta Devi, the run-up to Diwali is always hectic. It’s the time to sow wheat and sell sugarcane in the mandi (market), but they were happy. Even though their eldest son Mohit Kumar, 25, was fighting a conspiracy to murder charge (Section 120B of the IPC), he was at home with them.

Everything changed when Mohit got a death threat the week before Diwali. Geeta Devi alleges it was from the Chajju Ram gang, although she insists that her son had nothing to do with local gangs and vendettas.

However, Mohit grew up hearing stories of how his father and grandfather had been harassed by the Chajju gang. And he was seen as an ally of the Chippi gang, according to sub-inspector Jai Bhagwan of Kharawar police chowki in Rohtak.

Mohit Kumar, 25, met a fate similar to that of Anand Malik, the youngest of the Chajju sons, gunned down in 2018. Mohit, said to be an informant for the Chippi gang, faced a criminal conspiracy charge for Malik’s murder | Jyoti Yadav | ThePrint

Mohit was gunned down in front of Chajju’s deserted three-storey house by six men while returning from the fields in the afternoon.

“He ran for his life but the gang fired indiscriminately. At least a dozen bullets were shot at him and he finally collapsed,” says neighbour Rajender, 85, who lives just a few metres away and claims to have seen what happened.

In Karor, where an eye-for-an-eye and a tooth-for-a-tooth is almost a motto, villagers do not want another decade of murders. They want peace.

“The entire village is rallying behind me. It’s a miracle,” says Mohit’s father Ajit Malik. He stresses that he does not want revenge, but justice and insists that he will not be run out of his hometown. But he has asked the authorities for permission to carry arms to protect his family.

“We have three demands. First, give our family an arms licence so that we can protect ourselves. Second, set up a permanent police chowki in the village, and third, arrest all of the men involved in my son’s murder,” Ajit says.

The first murder case in 1998

Chajju and his sons were first named in a murder case in 1998, but there are different stories about the circumstances leading up to it.

According to village lore, a slap and a bruised ego led to the killing. Another version speaks of a man paying with his life for dancing in front of Chajju’s house despite warnings.

But former village head Rajesh Malik, better known here as Puru Sarpanch, dismisses these stories.

“It began with a wedding procession,” says Puru, 53. According to him, when a baraat reached Chajju Ram’s house, one of his sons, Shri Bhagavan, fired in the air, and ended up killing the groom’s cousin with a stray bullet. He was booked for murder, but witnesses turned hostile.

Emboldened, the gang then allegedly hijacked the next village panchayat elections.

“They captured the election with their proxy candidates. In the 2005 election, not a single person stood against the gang. It’s like being at gunpoint for years,” says Puru.

He further alleges that the gang extorted retired Army men, demanding 25 per cent of their pensions. “People who got jobs in Delhi had to give them 15 per cent of their earnings,” he adds.

But there was another criminal power centre in the area— the Chippi gang, led by an OBC family, which was also involved in the illegal liquor trade.

The young (Chippi) boys grew up in some part of Delhi and nobody ever heard from them, until they returned to take revenge

-Puru Sarpanch

Villagers claim the Chajju gang shot dead Ambu, the brother of Chippi patriarch Rame Kumar, leaving his body on the railway track.

“They wiped out Ambu and the remaining Chippi brothers,” Puru says. Although FIRs were filed, there was no follow-up. Rame’s wife ended up fleeing from the village in the dead of the night with her two sons Anil and Somvir in 2002.

“The young boys grew up in some part of Delhi and nobody ever heard from them, until they returned to take revenge,” says Puru.

In 2009, the Chippi boys allegedly killed Chajju Ram’s grandson Rakesh, alias Bintoo, and then, in 2012, two of his sons.

Karor is enacting a generational drama that carries on revenge much like the ‘baap ka, dada ka, sabka badla lega’ line from Gangs of Wasseypur. It’s a Haryanvi Godfather, but with never-ending series of sordid sequels.

Puru Sarpanch plays a central role in this saga.

“It was Puru Sarpanch who brought the Chippi boys to take revenge,” SI Jai Bhagavan says.

In 2009, Puru was booked for conspiracy to murder for providing information to the Chippi gang about Bintoo and stayed in jail until he got bail in 2011. He was also arrested for the 2012 murders for criminal conspiracy and spent eight years in jail before getting bail.

As for the Chippi sons, Somvir was arrested in 2009 and is currently out on bail, and Anil was on the run until 2011 and is currently behind bars. The trials for both murder cases are in progress.

Puru denies any role in the murders, but if anyone was driven by a need for vengeance it was him. It’s his wife and aunt who were murdered on Diwali in 2008.

While the Chajju gang draws hate, the villagers, even the Jats, are sympathetic toward the Chippi family.

Spiral of bloodlust

Puru first crossed swords with the Chajju gang to protect his land, but ended up paying with blood.

In 2006, Chajju’s sons demanded 40 bighas of land from his 105 bighas and he refused, he recalls.

He says this led to the gang harassing him for two years but he had the clout and wealth to hold them off. In 2008, the gang made a chilling announcement: the Puru family wouldn’t celebrate Diwali that year.

Used to such threats, he did not pay heed.

Diwali, 28 October that year, started on a festive note. Puru’s wife and aunts prepared for the puja, excited children ran amuck, and elders puffed happily on their hookahs. Then, around 6 pm, shots rang out. Puru’s wife and aunt died on the spot in front of horrified family members.

Finally, the police turned their gaze on Karor village, with V Kamaraja, IG of Rohtak range at the time, deploying a 15-member team to bring down the gang.

When Dilbagh and Shri Bhagavan were killed by the Chippi gang, no villager went to the funeral. When the police left, people made halwa to celebrate

-Ajit Malik, Mohit Kumar’s father

A 1987-batch officer, Kamaraja retired in 2015 and now lives in his home state Tamil Nadu. He recalls another village, Mandothi in Jhajjar district, that was terrorised by a family gang in a similar fashion.

“Even a small thing such as not giving way on the road can lead to a murder. This gang-lord pride is about manliness, and they execute it in the smallest instances,” Kamaraja explains.

Three of Chajju’s sons were the main accused in the 2008 Diwali murders. But before the trial ended, two of them— Dilbagh and Shri Bhagavan—were brazenly gunned down in 2012 when they were being escorted to court in a police van.

“When Dilbagh and Shri Bhagavan were killed by the Chippi gang, no villager went to the funeral. A few policemen cremated them. When the police left, people made halwa to celebrate,” recalls Mohit Kumar’s father Ajit.

While the Chajju gang draws hate, the villagers, even the Jats, are sympathetic toward the Chippi family.

Puru is a local village hero, but he doesn’t want to take ‘credit’. “I didn’t bring them [the Chippi sons] back,” he says. “The cases against me are still pending as no one from the Chajju gang deposed against me in court.”

Whenever there’s a land dispute, a familiar refrain often echoes: Tham layoge kabja, Chajju ke ho kya—You will seize our land, who do you think you are, Chajju’s sons?

A change of guard

The environment of fear in the village started changing only after 2010 or so. Chajju died of natural causes around this period and there was a change of guard in the village panchayat.

After the murders of wife and aunt, Puru Sarpanch made it his life’s mission to bring down the Chajju gang.

When he was still incarcerated for his alleged role in the 2009 murder of Chajju’s grandson, he decided to contest the panchayat election in 2010.

“I filed my nomination from the jail. I’d already sent my two sons and a daughter to my sister’s house in 2008 for their safety,” he says.

The results were astonishing. In the previous election, the Chajju gang’s candidate had been elected unopposed, with no one else daring to file a nomination. But in the 2010 election, 1,436 votes were cast and Puru won by a landslide.

“Only 20 votes went to the Chajju gang,” says Puru.

After securing bail in 2011, Puru Sarpanch’s first move was to try and bring back the families who were hounded out of Karor by the Chajju gang. He turned to political leaders for help.

“With the help of Deepender Hooda (Congress leader and whose father Bhupinder was CM at the time), I got an arms licence to protect myself and the family,” he says.

Puru prepared a comprehensive file documenting 39 recorded crimes committed by the Chajju gang and submitted it to the CM’s office in 2011. According to his records, the gang had obtained six arms licences in the names of the family’s women. These licences were later cancelled by various DCs.

But over a decade on, most of those who fled still haven’t returned.

Also Read: Wild card to wildlife, Elvish Yadav has ‘systumm’ wrapped around his finger

‘Chajju ke ho kya?’

Just a few kilometres off NH-10, Karor has little to distinguish it. Besides the fame of Jagbir Kakoriya, a popular singer from the Dhanak SC community, and ace wrestler Sumit Malik, the village is primarily associated with tales of terror. It’s a wasteland of bad memories.

“For ten years, all the Scheduled Caste residents either worked in their fields or in the Chajju gang’s dairy business. They were bonded labourers,” Puru alleges. “They worked without a single penny.”

Most of his energy is now focused on his sons— one is a lawyer and one is a four-time national gold medallist in wushu.

Karor is still on high alert. A police gunman stands guard outside Mohit’s house, and village representatives hold frequent meetings with the DSP and district administration for updates. There’s a 24-hour police presence. Every few hours, a police van circles the village.

But in Karor, where memories are long and revenge killings are served cold, villagers fear the fallout when the police leave.

For now, Chajju Ram’s house is quiet. It has been decaying slowly ever since IPS officer Kamaraja’s team sealed it in 2011. But the gang’s notoriety transcends these physical confines. Chajju’s land-grabbing tactics still echo across different corners of Haryana. Whenever there’s a land dispute, a familiar refrain can still be heard: Tham layoge kabja, Chajju ke ho kya—You will seize our land, who do you think you are, Chajju’s sons?

(Edited by Asavari Singh)